The tragic landscape: caspar david friedrich | thearticle

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

The catalogue for the exhibition _Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature _(Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, until May 11) is excellent on his doom-laden, metaphysical landscapes, but says

very little about the man who created them. Norbert Wolf’s short study _Friedrich_ (Taschen, 2012) reveals details about his character, interests and tastes, his students, finances and

wife. He loved to trek in the mountains, but his travels were limited by the Napoleonic wars and his hatred of France. In his whole life (1774-1840) the artist never once visited Paris,

never saw the Alps, Italy or the Mediterranean coast. Friedrich, the son of a pious Lutheran candle-maker and soap-boiler, was born in Greifswald, a harbour town on the Baltic Sea in

northeast Germany. Between the ages of seven and seventeen he suffered three traumatic losses. His mother died in 1781; in 1787 his brother drowned while trying to save Caspar, who had

fallen through the ice; and his sister died of typhus in 1791. He spent four years at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, and lived most of his life in culturally rich Dresden.

As a painter, Friedrich remained faithful to his original drawings, and used thin transparent glazes that left no trace of the brush on the surface. The Prussian Crown Prince and the future

Czar Nicholas I visited his studio and bought his paintings. A celibate bachelor, he did not marry until 1818 when he was in his forties. He then said, “it’s a droll business when a fellow

has a wife” and had to buy a lot of furniture including “a bed of sin”. Caroline Bommer, twenty years younger, was a cheerful, humorous Saxon woman; Friedrich had a gruff exterior and

unsociable nature, and was soon consumed by irrational jealousy. The murder of a close painter-friend in 1820 plunged him into a deep and long-lasting depression. A stroke in 1835 left his

arms and legs partly paralysed, and prevented him from painting in oils, though he continued to sketch in watercolour and ink. He died five years later. Friedrich’s work suggests the

intense yearning for the absolute that the Greek author Longinus (not mentioned in this catalogue) had defined in “On the Sublime” (c.100 CE): “man’s ability, through feeling and words, to

reach beyond the realm of the human condition into greater mystery.” Friedrich declared: “The task of a work of art is to recognize the spirit of nature and, with one’s whole heart and

intention, to saturate oneself with it and absorb it and give it back again in the form of a picture. . . . I must surrender myself to what surrounds me, unite myself with its clouds and

rocks, in order to be what I am. I need solitude in order to communicate with nature.” Like his close contemporary William Wordsworth, he longed to be absorbed “in earth’s diurnal course /

With rocks, and stones, and trees.” Friedrich portrayed mountain glory and mountain gloom, and his art is contradictory: both serene and turbulent, visionary and destructive. His paintings

are unknowable and transcendent, meditative and melancholy, eerie and enigmatic. They suggest dreams, love and loss; grief, mourning and alienation; “soaring grandeur and boundless

awe-inspiring heights.” But his “foggy vistas, mysterious mountains and moonlit landscapes,” his tiny distant figures overshadowed by nature, live in a world of unrelieved darkness and

nightmare. They are also gloomy and morose, haunting and enigmatic, angst-ridden and ominous. As Robert Frost wrote of an apocalyptic storm, “There would be more than ocean water broken /

Before God’s last Put out the light was spoken.” Toward the end of his life Friedrich became increasingly depressed and exclaimed, “Today for the first time the normally so glorious

countryside cries out to me of decay and death, where before it has only smiled to me of joy and life.” Like the ominous birds in Edgar Poe’s morbid, death-obsessed, “ghoul-haunted

woodlands,” Friedrich’s ravens announce disaster and death. _Cemetery in Moonlight with an Owl _(1834) portrays the tragedy of landscape. A contributor notes, “the freshly dug grave in the

foreground and tilted gabled crosses mark burial mounds beyond. A lone owl, traditional symbol of death, perches on the gravediggers’ spade.” Friedrich’s damned outcasts and solitary

wanderers also resemble Lord Byron’s dark, brooding, tragic heroes. In _Oak Tree in the Snow _(1827-28) and other works, his gnarled, twisted and leaf-torn anthropomorphic branches are like

the arms and fingers of drowning or half-buried men desperately reaching out for the help that fails to save them. Cemetery in Moonlight with an Owl Caspar David Friedrich, 1834 The artist

rarely portrayed a close-up face, except his own. In _Caspar David Friedrich in His Studio _(1811) he is seated in profile, with blond hair combed over his forehead and flourishing

side-whiskers. He wears a long, greyish-blue, high-collared jacket, trousers, white stockings and grey slippers. In Spartan surroundings his unusually-long maulstick crosses his

paintbrush and almost touches the ceiling. The table on the right has an open paint-box, rags and colored bottles. Two palettes, a triangle and a T-square hang on the wall between the

windows. The closed door on the left and boarded-up window on the right frame the open window, divided into four squares. It reveals the cloudy sky beyond and provides exactly the kind of

streaming light he needs. The painter’s legs, chair legs, table legs and high easel form verticals that enclose him as he leans forward to concentrate on completing his landscape. Friedrich

may have seen an engraving of Francisco Goya’s comparable _Artist in His Studio _(c.1795). Goya, who painted at night with candles fixed to holders in his hat, is posed at his easel

holding his brush and palette. He has a drooping mustache and dangling unruly hair, and wears a high black hat circled by a buckled ribbon, a red shirt, brown jacket with silver-buttons and

tight trousers. Standing rather than sitting before an open window and more elaborately dressed, Goya looks at the viewer rather than the painting. Artist in His Studio, Francisco Goya

(c.1795). _Woman at the Window_ (1822) takes place in the same room as Friedrich’s studio. His young wife has thick brown hair, long neck and tall collar, and wears a high-waisted greenish

dress, white stockings and tan slippers. Seen from behind, she looks out of the window and sees a ship’s mast piercing the clouds and poplars on the bank of the Elbe River. A contemporary

German poem suggested the subtle effects of seeing the painter’s characteristic pose: “O no, benevolent mystery / do not turn your face to me! / Leave me silent, trembling in soulful

anticipation.” The artists’ wife, Caroline Friedrich, Friedrich described _Monk by the Sea_ (1808-10) as “a seascape, in the foreground a barren, sandy beach, then a restless sea, and

thence, the air. On the beach a man is walking, deep in thought, in a black robe; gulls fly around him, fretfully shrieking, as if to warn him not to risk the brash sea”—though it’s

unlikely that the landlubber monk would go for a sail or a swim. The painting is divided into cloudy land, wavy sea and lowering sky. The tiny bareheaded monk, diminished by the

overwhelming environment, stands still on the shore, unmoved by the gulls that flap above him. Friedrich’s contemporary, the writer Heinrich von Kleist (who committed suicide in 1811),

called _Monk by the Sea_ “a miraculous painting, a visual and existential apocalypse”, which reflected his own thoughts and feelings. It’s surprising that there’s no mention of Friedrich in

the recent biographies of his cataclysmic soul mates Richard Wagner, Friedrich Nietzsche and Edvard Munch. The Monk by the Sea, Caspar David Friedrich, (1808-10) In _Chalk Cliffs on Rügen

_(1818) the canopy of leafy trees and oval of the frozen cliffs form a circle with three figures in the foreground. An older man on his knees and looking downward has discarded his top hat

and cane. He seems about to tumble into the jagged chalk cliffs that look more like Antarctica than an island in the Baltic Sea. On his left a seated woman, seen in profile with dangling

curls and a high-waisted long red gown, extends her right arm and index finger in a unheeded warning. On the right a contemplative younger man with a floppy velvet hat ignores his

companions. The cliffs form a V at the bottom of the circle and point to a single white sail in the distant center of the picture. Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann, W. H. Auden, Christopher

Isherwood and Stephen Spender were also attracted to Rügen and spent summer holidays on the island. Caspar David Friedrich’s Chalk Cliffs on Rügen _The Sea of Ice_ (1823-24) portrays a

massive glacier on the left, and sharp-edged ice packs thrusting out of the frozen sea and slowly crushing a doomed ship, whose black stern decorated with red paint sinks below the surface.

They all point left at a 45o angle toward the storm that caused the disaster. Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798) captures the chaotic mood of the picture: The ice was here,

the ice was there, The ice was all around: It crack’d and growl’d, and roar’d and howl’d, Like noises in a swound! Caspar David Friedrich’s Chalk Cliffs on Rügen Friedrich’s painting

foreshadows the famous 1915 photograph of the wrecked _Endurance_, trapped, crushed and sunk in the Arctic ice pack. Like Pieter Brueghel’s _Landscape with the Fall of Icarus_ (1560) and

_Hunters in the Snow_ (1565), Friedrich’s _The Watzmann _(1824-25), a peak in the Bavarian Alps that he had never seen, shows towering Alpine mountains erupting unrealistically from the

northern landscape. _Hunters in the Snow, _Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565 In Shakespeare’s _As You Like It,_ Jaques gives a famous speech on the Seven Ages of Man: infant, child, lover,

soldier, judge, mature man and old man. _The Stages of Life_ (1834) portrays five people on the rocky shore watching five corresponding ships, with high masts and billowing sails, floating

in the deep blue sea beneath a lemon and violet sky. These figures represent a blond infant, child and female lover seen in profile, a mature man facing the viewer and an old man facing the

calm sea. The child holds up a blue-and-yellow Swedish flag recalling that Greifswald’s region, Western Pomerania, belonged to Sweden until 1815. Caspar David Friedrich: _The Stages of

Life_ (1834) The Romantic poets praised the beauty, majesty and awesome power of the Alps, jutting up like church spires, the closest points on earth to heaven. In _The Prelude _(1805),

Wordsworth described the tremendous force of the torrents that poured down from the mountains. A decade later Shelley wrote about the towering and dangerous snow, ice and rocks in a poem

about Mont Blanc (1816), the highest peak in Europe. In _Modern Painters _(1843) John Ruskin, a keen climber, felt a spiritual response to the mountains that stretched toward heaven and

were “the centres not only of imaginative energy, but of purity”. Ruskin was a great admirer of J.M.W. Turner, who painted the swirling colours and vertiginous heights of the Alps.

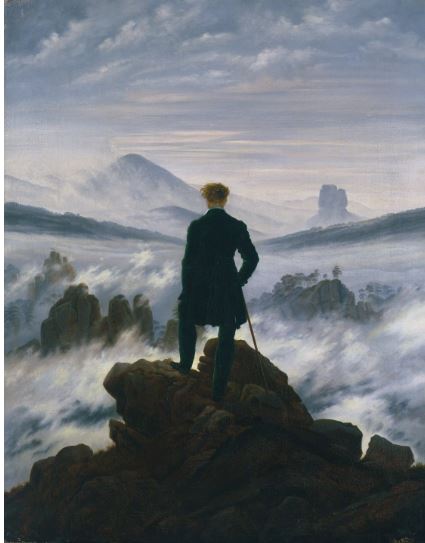

Friedrich’s _Wanderer above the Sea of Fog_ (1817), his most famous work, portrays a man with curly red hair and green-velvet coat triumphantly standing on a mountain top. He surveys the

peaks that rise through the fog below him like massive shrouded fingers reaching for the sky. The mountain landscape that surrounds him is also seen through the spaces between his bent

right arm, his spread legs and his thin tilted cane. The Wanderer has a Greta Garbo-like desire to be alone, and looks far out and in deep. But it’s difficult for him to turn round and

retreat without falling from his precarious perch and immersing himself in nature by plunging into the abyss. In _The Concept of Dread_ (1844), the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (not

mentioned in the catalogue) captured the mood of this painting by using the example of a man standing on the edge of a tall cliff: “When the man looks over the edge, he experiences an

aversion to the possibility of falling, but at the same time, the man feels a terrifying impulse to throw himself intentionally off the edge. That experience is anxiety or dread because of

our complete freedom to choose to either throw oneself off or to stay put.” Friedrich’s reputation was as precarious as his Wanderer. A contributor notes that by1820 “most of his canvases

had entered private collections, where, hidden from public view, they sank swiftly into oblivion. And so did Friedrich himself.” He was largely forgotten after his death in 1840. The 1906

German Centenary Exhibition in Berlin rediscovered Friedrich and recognized him as a great painter. But his reputation sank again when he became one of Hitler’s favorite painters. It was

revived once again in the giant retrospective at the Hamburger Kunsthalle in 1974. The impressive current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum pays him a well-deserved tribute. Kenneth

Clark’s _Landscape into Art_ (1949) brilliantly summarised Friedrich’s great achievement: “No one has expressed more poignantly the gloom of solitude and the sadness of unfulfilled

expectation.” _Jeffrey Meyers has published Painting and the Novel, The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis, Impressionist Quartet, Modigliani: A Life and Alex Colville: The Mystery of the

Real._ A MESSAGE FROM THEARTICLE _We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and

we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation._