Has 'song of the south' never been released on home video in the us?

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

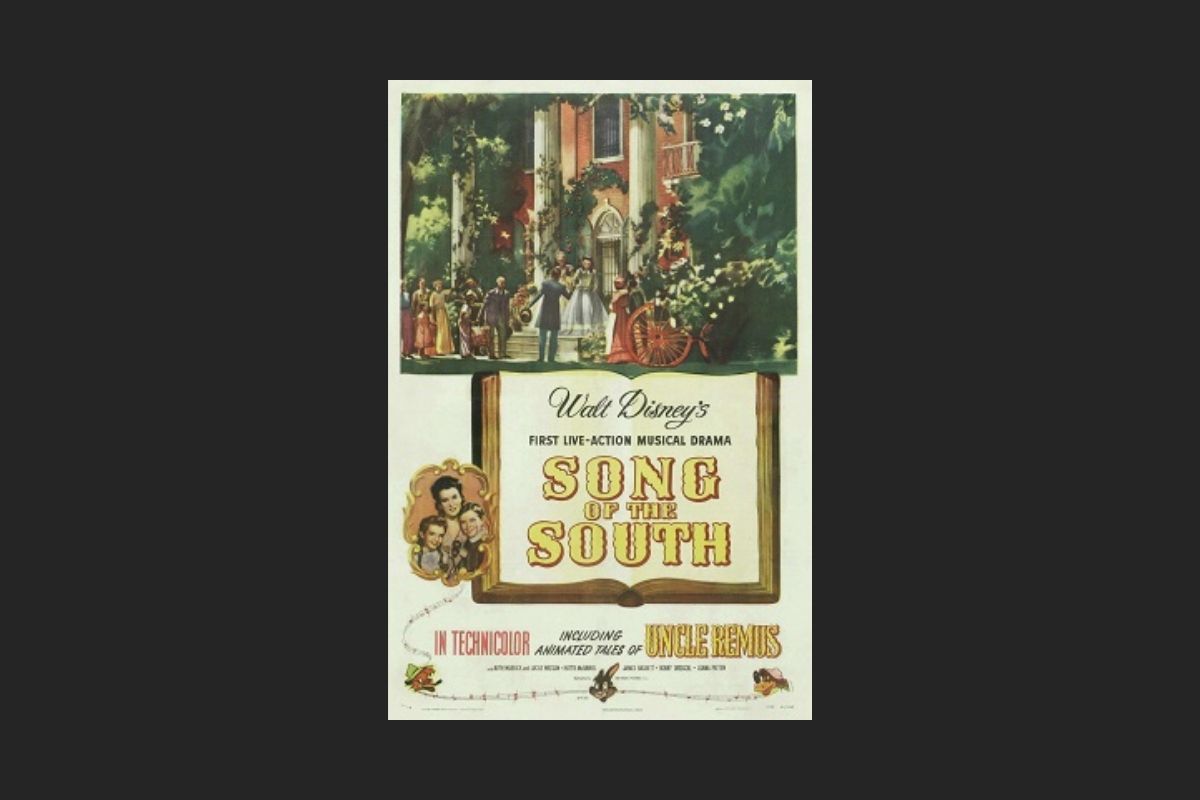

Claim: The film "Song of the South" has never been released on home video in the USA. _Song of the South,_ a 1946 Disney film mixing animation and live action, was based on the

"Uncle Remus" stories of Joel Chandler Harris. Harris, who had grown up in Georgia during the Civil War, spent a lifetime compiling and publishing the tales told to him by former

slaves. These stories — many of which Harris learned from an old Black man he called "Uncle George" — were first published as columns in the _Atlanta Constitution_ and were later

syndicated nationwide and published in book form. Harris's Uncle Remus was a fictitious old slave and philosopher who told entertaining fables about Br'er Rabbit and other woodland

creatures in a Southern Black dialect. _Song of the South_ consists of animated sequences featuring Uncle Remus characters such as Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, and Br'er Bear,

framed by live-action portions in which Uncle Remus (portrayed by actor James Baskett, who won a special Oscar for his efforts) tells the stories to a little white boy upset over his

parents' impending divorce. Although some Blacks have always been uneasy about the minstrel tradition of the Uncle Remus stories, the major objections to _Song of the South_ have had to

do with the live-action portions. The film has been criticized both for "making slavery appear pleasant" and "pretending slavery didn't exist," even though the film

(like Harris' original collection of stories) is set after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. Still, as folklorist Patricia A. Turner wrote: > Disney's 20th century

re-creation of Harris's frame story is much > more heinous than the original. The days on the plantation located > in "the United States of Georgia" begin and end with

unsupervised > Blacks singing songs about their wonderful home as they march to and > from the fields. Disney and company made no attempt to to render the > music in the style of

the spirituals and work songs that would have > been sung during this era. They provided no indication regarding the > status of the Blacks on the plantation. Joel Chandler Harris set

his > stories in the post-slavery era, but Disney's version seems to take > place during a surreal time when Blacks lived on slave quarters on a > plantation, worked diligently

for no visible reward and considered > Atlanta a viable place for an old Black man to set out for. > > Kind old Uncle Remus caters to the needs of the young white boy > whose

father has inexplicably left him and his mother at the > plantation. An obviously ill-kept Black child of the same age named > Toby is assigned to look after the white boy, Johnny.

Although Toby > makes one reference to his "ma," his parents are nowhere to be seen. > The African-American adults in the film pay attention to him only > when he neglects

his responsibilities as Johnny's playmate-keeper. > He is up before Johnny in the morning in order to bring his white > charge water to wash with and keep him entertained. >

> The boys befriend a little blond girl, Ginny, whose family clearly > represents the neighborhood's white trash. Although Johnny coaxes > his mother into inviting Ginny to his

fancy birthday party at the > big house, Toby is curiously absent from the party scenes. Toby is > good enough to catch frogs with, but not good enough to have > birthday cake

with. When Toby and Johnny are with Uncle Remus, the > gray-haired Black man directs most of his attention to the white > child. Thus Blacks on the plantation are seen as willingly

> subservient to the whites to the extent that they overlook the needs > of their own children. When Johnny's mother threatens to keep her > son away from the old

gentleman's cabin, Uncle Remus is so hurt that > he starts to run away. In the world that Disney made, the Blacks > sublimate their own lives in order to be better servants to the

> white family. If Disney had truly understood the message of the > tales he animated so delightfully, he would have realized the extent > of distortion of the frame story. The

NAACP acknowledged "the remarkable artistic merit" of the film when it was first released, but decried "the impression it gives of an idyllic master-slave relationship".

Disney re-released the film in 1956 but then kept it out of circulation all throughout the turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s. In 1970 Disney announced in _Variety_ that _Song of the

South_ had been "permanently" retired, but the studio eventually changed its mind and re-released the film theatrically in 1972, 1981, and again in 1986 for a fortieth anniversary

celebration. Although the film has only been issued for the home video market in various European and Asian countries, Disney's reluctance to market it in the USA is not a reaction to

an alleged threat by the NAACP to boycott Disney products. The NAACP fielded objections to _Song of the South_ when it premiered, but it has no current position on the movie. SOURCES

Liebenson, Donald. "Should 'Dated' Films See the Light of Today?" _Los Angeles Times._ 7 May 2003 (p. E4). Lohmann, Bill. "'Song of the South'

Returns." _UPI Arts & Entertainment._ 11 November 1986. Turner, Patricia A. _Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies._ New York: Anchor Books, 1994. ISBN 0-385-46784-2

(p. 114). Ringel, Eleanor and Steve Murray. "Coloring Disney's World." _The Atlanta Journal and Constitution._ 31 July 1994 (p. N1). _The Times-Picayune._

"Will 'The South' Ever Sing Again?" 5 December 1993 (TV Focus; p. T10).