No evidence for prolactin’s involvement in the post-ejaculatory refractory period

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT In many species, ejaculation is followed by a state of decreased sexual activity, the post-ejaculatory refractory period. Several lines of evidence have suggested prolactin, a

pituitary hormone released around the time of ejaculation in humans and other animals, to be a decisive player in the establishment of the refractory period. However, data supporting this

hypothesis is controversial. We took advantage of two different strains of house mouse, a wild derived and a classical laboratory strain that differ substantially in their sexual

performance, to investigate prolactin’s involvement in sexual activity and the refractory period. First, we show that there is prolactin release during sexual behavior in male mice. Second,

using a pharmacological approach, we show that acute manipulations of prolactin levels, either mimicking the natural release during sexual behavior or inhibiting its occurrence, do not

affect sexual activity or shorten the refractory period, respectively. Therefore, we show compelling evidence refuting the idea that prolactin released during copulation is involved in the

establishment of the refractory period, a long-standing hypothesis in the field of behavioral endocrinology. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

Article 08 December 2022 DEFINITION OF THE ESTROGEN NEGATIVE FEEDBACK PATHWAY CONTROLLING THE GNRH PULSE GENERATOR IN FEMALE MICE Article Open access 02 December 2022 COMMON AND

FEMALE-SPECIFIC ROLES OF PROTEIN TYROSINE PHOSPHATASE RECEPTORS N AND N2 IN MICE REPRODUCTION Article Open access 07 January 2023 INTRODUCTION Sexual behavior follows the classical sequence

of motivated behaviors, terminating with an inhibitory phase after ejaculation: the post-ejaculatory refractory period (PERP)1. The PERP is highly conserved across species and includes a

general decrease in sexual activity and also inhibition of erectile function in humans and other primates2. This period of time is variable across and within individuals and is affected by

many factors, such as age3,4 or the presentation of a new sexual partner5,6. The PERP is thought to allow replacement of sperm and seminal fluid, functioning as a negative feedback system

where by inhibiting too-frequent ejaculations an adequate sperm count needed for fertilization is maintained7,8. Several lines of evidence have suggested the hormone prolactin (PRL) to be a

key player in the establishment of the PERP9,10. PRL is a pleiotropic hormone, first characterized in the context of milk production in females, but for which we currently know several

hundred physiological effects in both sexes11,12. The association of PRL to the establishment of the PERP in males is based on several observations. First, it was shown that PRL is released

around the time of ejaculation in humans and rats13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Anecdotally, no PRL release has been observed in a subject with multiple orgasms22. Second, chronically abnormal

high levels of circulating PRL are associated with decreased sexual drive, anorgasmia, and ejaculatory dysfunctions23,24. Finally, removal of PRL-producing pituitary tumors or treatment with

drugs that inhibit PRL release reverse sexual dysfunctions25,26. Taking these observations into consideration, it has been hypothesized that the PRL surge around the time of ejaculation

plays a role in the immediate subsequent decrease of sexual activity, the hallmark of the PERP. In fact, this idea is widespread in behavioral endocrinology textbooks27 and the popular press

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Refractory_period; https://www.humanitas.net/treatments/prolactin). PRL is primarily produced and released into the bloodstream from the anterior

pituitary11,28 and consistent with its functional diversity, PRL receptors are found in most tissues and cell types of the body29,30. Therefore, PRL may depress sexual activity directly, via

PRL receptors present in the male reproductive tract. In fact, PRL has been shown to impact the function of accessory sex glands and to contribute to penile detumescence31. PRL can also

affect central processing, as it can reach the central nervous system either via circumventricular regions lacking a blood–brain barrier32 or via receptor-mediated mechanisms33, binding its

receptors which have widespread distribution, including in the social brain network34. Hence, circulating PRL can impact the activity of neuronal circuits involved in the processing of

socio-sexual relevant cues and thus sexual performance. Circulating PRL reaches the central nervous system on a timescale that supports the rapid behavioral alterations that are observed

immediately after ejaculation (in <2 min)35. Through mechanisms that are not yet well established, PRL is known to elicit fast neuronal responses36 besides its classical genomic

effects37. In summary, circulating PRL can impact several systems involved in sexual behavior on a timescale compatible with the establishment of the PERP. However, despite data supporting

the involvement of the ejaculatory PRL surge in the establishment of the PERP, this hypothesis has received numerous critics2,3,38,39,40. While in humans it is well established that

chronically high levels of PRL reduces libido24, some authors suggest that those results were erroneously extended to the acute release of PRL around ejaculation2,3,38,39,40. Furthermore,

there is controversy in relation to PRL dynamics during sexual behavior, since in most studies PRL levels were quantified during fixed intervals of time, and not upon the occurrence of

particular events, such as ejaculation. In fact, some reports in rats suggest that PRL levels are elevated through the entire sexual interaction41,42. Finally, formal testing of the impact

of acute PRL manipulations on sexual activity and performance is still missing (but see ref. 43 for an acute manipulation in humans). In the present study, we tested the role of PRL in

sexual activity and in the establishment of the PERP in the mouse. The sequence of sexual behavior in the mouse is very similar to the one observed in humans44, making it an ideal system to

test this hypothesis. Also, we took advantage of two strains of inbred mice that are representative of two different mouse subspecies (C57BL/6J: laboratory mouse, predominantly _Mus musculus

domesticus_ and PWK/PhJ: inbred wild-derived, _Mus musculus musculus_45) and exhibit different sexual performance. Through routine work in our laboratory, we observed that while most BL6

males take several days to recover sexual activity after ejaculation, a large proportion of PWK males will re-initiate copulation with the same female within a relatively short period of

time. This difference in PERP duration can be taken to our advantage, widening the dynamic range of this behavioral parameter and increasing the probability of detecting an effect with

pharmacological manipulations. First, we show that there is PRL release during sexual behavior in male mice. Second, using a pharmacological approach, we show that acute manipulations of

prolactin levels, either mimicking the natural release during sexual behavior or inhibiting its occurrence, do not affect sexual activity or shorten the refractory period, respectively.

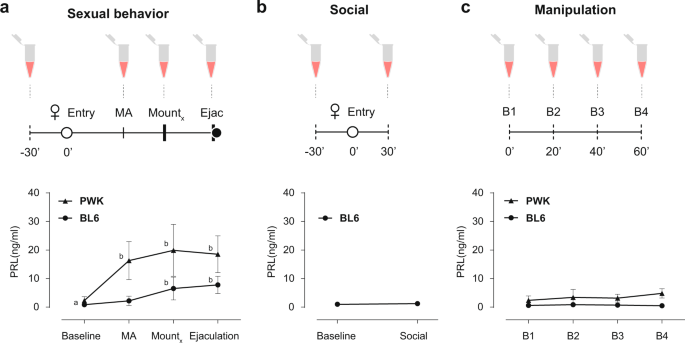

RESULTS PROLACTIN IS RELEASED DURING SEXUAL BEHAVIOR IN MALE MICE We first asked if PRL is released during copulation in the two strains of male mice. To monitor PRL dynamics during sexual

behavior we took advantage of a recently developed ultrasensitive ELISA assay that can detect circulating levels of PRL in very small volumes of whole blood (5–10 μl), allowing the

assessment of longitudinal PRL levels in freely behaving mice46. Sexually trained laboratory mice (C57BL/6J, from here on BL6) and inbred wild-derived mice (PWK/PhJ, from here on PWK) were

paired with a receptive female and allowed to mate (see “Methods” for details). During the sexual interaction males were momentarily removed from the cage to collect tail blood after which

they returned to the behavioral cage, resuming the sexual interaction with the female. We collected blood samples upon the execution of pre-determined, easily identifiable, behavioral events

that correspond to different internal states of the male: before sexual arousal (baseline, before the female was introduced in the cage), at the transition from appetitive to consummatory

behavior (MA, mount attempt, immediately after the male attempted to mount the female), during consummatory behavior (mount, after a pre-determined number of mounts with intromissions, BL6 =

5 and PWK = 3), and after ejaculation (ejaculation, after the male exhibited the stereotypical shivering, falling to the side and separating from the female) (Fig. 1a, see “Methods” for

details). Baseline levels of circulating PRL in male mice were low for both strains (BL6 0.86 ± 0.46; PWK: 2.31 ± 1.37 ng/ml; please see ref. 46 for BL6), but are significantly increased

during sexual interaction (Bl6: _F_3,7 = 21.26, _P_ < 0.0001; PWK: _F_3,8 = 17.18, _P_ < 0.0001; RM one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 1a). While in the case of BL6 males PRL levels only increased

during the consummatory phase, PRL levels in PWK males are significantly increased already at the transition from appetitive to consummatory behavior (Baseline vs MA 16.30 ± 6.67 ng/ml, _P_

= 0.001, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 1a). In both strains, PRL levels after ejaculation are similar to the levels reached during consummatory behavior (BL6 _P_ = 0.71 vs PWK _P_

= 0.95, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), in marked contrast to humans, where PRL seems to be released only around the time of ejaculation15. Contrary to PWK males, which in the presence

of a receptive female always engaged in sexual behavior and ejaculated, a large percentage of BL6 males never attempted to mount the female (15 out of 23, Supplementary Data 1). In such

case, the session was aborted after 30 min of social interaction and a blood sample was collected (Fig. 1b). In this case, PRL levels of BL6 males did not differ from baseline (baseline 0.99

± 0.67 vs social 1.25 ± 0.63; _P_ = 0.282, paired _t-_test), further suggesting that PRL is only released in the context of a sexual interaction. Because PRL is known to be released under

stress47 and to ensure that the changes observed in circulation are not a result from the blood collection procedure itself, all animals were initially habituated to the collection protocol

in another cage, alone. To ensure that the habituation protocol was effective, in a separate experiment we measured PRL levels in the absence of any behavior. Four blood samples were

collected 20 min apart from BL6 and PWK males in their home cage (Fig. 1c). In both cases, circulating PRL levels were not altered, ensuring that the observed increases were not caused by

the manipulation (Bl6: _F_3,7 = 2.08, _P_ = 0.18; PWK _F_3,7 = 2.94, _P_ = 0.11, RM one-way ANOVA). Together, these results demonstrate that PRL is released during sexual behavior in male

mice, but not during a social interaction or due to the blood collection protocol, prompting us to examine the role of PRL release during sexual behavior. ACUTE PROLACTIN RELEASE DOES NOT

INDUCE A REFRACTORY PERIOD-LIKE STATE To investigate if the increase in circulating levels of PRL that occurs during mating is sufficient to decrease sexual activity, a hallmark of the PERP,

we employed a pharmacological approach to acutely elevate PRL levels before the animals became sexually aroused and assess if the male mice behave as if in a PERP-like state. PRL is

produced in specialized cells of the anterior pituitary, the lactotrophs, and its release is primarily controlled by dopamine originating from the hypothalamus11. Dopamine binds D2 receptors

at the membrane of the lactotrophs, inhibiting PRL release. Suppression of dopamine discharge leads to disinhibition of lactotrophs, which quickly release PRL into circulation48,49. To

acutely elevate PRL levels, we performed an intraperitoneal injection of the D2 dopamine receptor antagonist domperidone, which does not cross the blood–brain barrier50,51, and measured PRL

levels 15 min after the procedure. As expected, domperidone administration lead to a sharp rise in the levels of circulating PRL (BL6: baseline 0.4957 ± 0.4789 vs Domp 12.54 ± 2.032, _P_

< 0.0001; PWK: baseline 4.82 ± 1.645 vs Domp 25.87 ± 7.154, _P_ < 0.0001, paired _t_-test) (Fig. 2a) of similar magnitude to what is observed during copulation (ejaculation time point

from Fig. 1a). Therefore, on a separate experiment we investigated how domperidone-treated male mice behave with a receptive female. If PRL is sufficient to induce a PERP-like state, treated

males should exhibit decreased sexual activity, which could be manifested in distinct manners, such as on the latency to initiate consummatory behavior or on the vigor of copulation. Each

male from the two strains was tested twice, once with vehicle and another time with domperidone, in a counterbalanced manner and all the annotated behaviors are depicted over time on Fig.

2b, c (see “Methods” for details). Some BL6 males did not reach ejaculation in one of the sessions. A similar frequency was observed among unmanipulated animals (Supplementary Data 1).

Despite differences in the dynamics of sexual behavior between BL6 and PWK males, administration of domperidone does not seem to affect sexual performance, as we could not detect any

significant difference in the latency to start mounting the female, frequency of attempts to mount the female, time taken to ejaculate, or proportion of animals that reached ejaculation

(Fig. 2d–g). Domperidone administration also does not seem to affect the dynamics of the sexual interaction across the session or within each mount (Fig. 2h, i, respectively) or other

measures of sexual behavioral performance (Supplementary Data 2). Moreover, the majority of males reached ejaculation (latency to ejaculate since female entry: BL6:16.2 ± 7 with a maximum of

62 min; PWK: 12.3 ± 6.7 with a maximum of 59 min, Supplementary Data 2) within the time window where PRL levels remain elevated after domperidone administration46. In summary, domperidone

administration, which causes an acute elevation of circulating PRL levels similar to what is observed at the end of copulation, does not have an inhibitory effect on any behavioral parameter

related to sexual activity on the two strains of mice tested, that is, it does not induce a PERP-like state. BLOCKING PROLACTIN RELEASE DURING COPULATION DOES NOT DECREASE THE DURATION OF

THE REFRACTORY PERIOD The release of PRL which is observed during sexual behavior has been proposed to be crucial in the establishment of the PERP9. To test this hypothesis, we acutely

inhibited PRL release during sexual behavior by taking advantage of bromocriptine, a D2 receptor agonist. Bromocriptine’s activation of D2 receptors on the lactotrophs’ membrane blocks PRL

release, a well-established procedure to inhibit the discharge of this hormone from the pituitary34,52. If PRL is indeed necessary for the establishment of the PERP, we expected that after

ejaculation, drug-treated males would regain sexual activity faster than controls. To test bromocriptine’s efficiency in blocking PRL release during sexual behavior, we first injected a

group of males with bromocriptine (or vehicle) and measured PRL levels at three time points: (i) before the drug or vehicle injection, (ii) before the female was inserted in the cage, and

then (iii) after ejaculation (Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3a, bromocriptine administration efficiently blocked PRL release in both subspecies of mice, since PRL levels after ejaculation are

not different from baseline (BL6: B1 vs ejac, _P_ = 0.3, B2 vs Ejac _P_ = 0.99; PWK: B1 vs ejac, _P_ = 0.97, B2 vs Ejac _P_ = 0.99; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test after RM two-way Anova).

In a separate experiment we then tested the effect of the pharmacological manipulation on the establishment of the PERP and its duration. In this case, the male and female were allowed to

remain in the cage undisturbed for a period of up to 2 h after ejaculation. Each male from the two strains was tested twice, once with vehicle and a second time with bromocriptine, in a

counterbalanced manner. Each session ended once the male performed the first attempt of copulation after ejaculation (red diamonds) or after 2 h if no attempt was made (Fig. 3b, see

“Methods” for details). All the annotated behaviors are depicted over time in Fig. 3b, c (see “Methods” for details). As shown in Fig. 3d, inhibiting PRL release during sexual behavior did

not change the proportion of male mice of the two strains that reached ejaculation (Supplementary Data 1) or regained sexual activity in the 2 h after ejaculation (corresponding to the

proportion of red diamonds in Fig. 3c). In addition, and contrary to what was expected, we observed a significant increase in the PERP of PWK males (Fig. 3e, veh: 21.7 ± 4.18 vs bromo: 35.4

± 16.3, _P_ = 0.007 by Wilcoxon signed rank test). Administration of bromocriptine also seems to affect the initial sexual arousal, as we could detect a decrease in the latency to start

mounting the female (Fig. 3f, trend for B6 males and significant for PWK, veh: 4.06 ± 4.35 vs bromo: 1.93 ± 1.13, _P_ = 0.06; and veh: 2.78 ± 1.7 vs bromo: 1.48 ± 0.55, _P_ = 0.01,

respectively, by Wilcoxon signed rank test). This observation was not due to an increase in activity/locomotion of the bromocriptine-treated males, as the average male speed before and after

the female entry was not affected by the manipulation, nor the distance between the pair (Supplementary Data 3). Despite the locomotor activity being the same, the average male speed

projected towards the female increased significantly for PWK males treated with bromocriptine as they moved in a goal-directed way, directionally towards the female (Supplementary Data 3).

Once consummatory behavior was initiated, control and bromocriptine-treated males exhibited similar levels of sexual performance, as we could not detect any difference in the frequency of

attempts to mount the female or time taken to reach ejaculation (Fig. 3g, h). Other aspects of the sexual interaction were also not altered (Supplementary Data 4). Furthermore, bromocriptine

administration does not seem to affect the dynamics of the sexual interaction across the session or within each mount (Fig. 3I, j, respectively). In summary, blocking PRL release during

copulation does not affect the proportion of animals that regain sexual activity within 2 h after ejaculation and contrary to what was expected, bromocriptine leads to an increase in the

duration of the PERP of PWK males. Except for a decrease in the latency to start mounting, maintaining circulating PRL low, at levels similar to what is observed prior to the sexual

interaction, does not affect any of the parameters of sexual performance analyzed in both strains of mice. DISCUSSION The PERP is highly conserved across species and is characterized by a

general decrease in sexual activity after ejaculation2. The pituitary hormone PRL is released during copulation and has been put forward as the main player in the establishment of the PERP9.

However, the involvement of PRL in the establishment and duration of the PERP is controversial and has not been formally tested2. Here we show that despite being released during copulation

as previously shown in other taxa, PRL is neither sufficient nor necessary for the establishment of the PERP. We first showed that PRL is released during copulation in male mice. The

proportion of BL6 males that engaged in sexual behavior when tail blood is collected is lower than the proportion of animals that copulated in the rest of the experiments, suggesting that

the procedure affects their sexual activity. However, once they start mating, all animals reached ejaculation. Importantly, once habituated, the procedure itself does not lead to PRL

release. This opens up the possibility to perform such type of experiments using an “within-animal” design, a very important point particularly when there is a large interindividual

variability, while decreasing the number of animals used. Despite being released during sexual behavior in mice, PRL dynamics are quite different from what has been observed in humans. In

men, PRL seems to only be released around the time of ejaculation15,16, and only when ejaculation is achieved16. Indeed, the fact that PRL surge was only observed when ejaculation was

achieved was one of the main results that lead to the idea that PRL may play a role in the acute regulation of sexual activity after orgasm in humans53. In contrast, in mice we observed an

increase in circulating levels of PRL in sexually aroused PWK males and in BL6 males during the consummatory phase. The discrepancy between our results and the results published by others

might be a result of the sampling procedure. Despite the fact that in human studies blood was continuously collected, PRL detection was performed at fixed time intervals and not upon the

occurrence of particular events, such as ejaculation. Therefore, when averaging PRL levels across individuals, each participant might be in a slightly different internal state. Also, because

PRL concentration is determined over fixed intervals of time, it is difficult to pinpoint the PRL surge to the time of ejaculation (even though the human studies show that sexual arousal

per se is not accompanied by an increase in PRL levels)9. To our knowledge, a single study assessed PRL levels during sexual behavior in male mice, stating that PRL is released after

ejaculation54. In this case, blood was also continuously sampled at fixed intervals of time. In contrast, in our study the blood was collected upon the execution of particular events, such

as the first MA, a pre-defined number of mounts and ejaculation. Thus, even though the intervals between PRL measurements are different for each mouse, we ensure that PRL levels are measured

for all individuals in a similar internal state. Independently of the differences in the dynamics of circulating PRL levels, the increase we observe seems to be specific to a sexual

encounter, since PRL levels in BL6 males that never attempt copulation remain unaltered from baseline. In order to test if PRL by itself is sufficient to decrease sexual activity, we

injected domperidone to induce an artificial PRL surge. In this case, the male mouse should behave like a male that just ejaculated: for example, exhibit longer latency to initiate the

sexual interaction, which in the case of BL6 mice should take days. Even though domperidone administration leads to circulating levels of PRL that are similar to the ones observed at the end

of a full sexual interaction, this manipulation did not cause any alteration in terms of sexual performance, as all behavioral parameters remained unaltered for both strains of mice.

Although most likely other neuromodulatory systems were affected by our manipulation (via PRL), the fact that the domperidone manipulation did not cause a PERP-like state might still be due

to the fact that the full repertoire of neuromodulators and hormones accompanying an ejaculation was not present55. Further experiments could test this idea by examining if combinations of

different neuromodulators and hormones administered together with PRL can induce a PERP-like state. Last, we asked if the elevation in PRL levels during sexual behavior is necessary for the

establishment and duration of the PERP. For that we took a complementary pharmacological approach, where we injected bromocriptine, a D2 receptor agonist that temporarily inhibits the

release of PRL. PRL levels after ejaculation in bromocriptine-treated males are similar to pre-copulatory levels. If PRL is indeed necessary to establish the PERP, we would expect a decrease

in its duration that should easily be observed in the PWK males (since they regain sexual activity on average 30 min after ejaculation) or even in the BL6 (which take days). We observed a

decrease in the latency to start mounting the female and, contrary to our expectation, a significant increase in the PERP duration of PWK males. We believe these effects may be mediated by

the direct effect of bromocriptine, rather than an effect of PRL itself. First, baseline PRL levels are already very low in male mice and therefore the manipulation most likely did not

affect them. Second, systemic administration of dopamine agonists has shown that anticipatory measures of sexual behavior are more sensitive to disruption than are consummatory measures of

copulation56,57. This agrees with our results, where we observed a significant decrease in the latency to initiate mounting with bromocriptine, while no other parameter of sexual performance

was affected. Interestingly, bromocriptine-treated PWK males seem more ballistic in their approach to the female, suggesting a more goal-directed behavior towards the female. Bromocriptine

(and domperidone) might also have an effect outside the central nervous system as D2 receptors are expressed in the human and rat seminal vesicles58. It is not known if direct manipulation

of these receptors in the seminal vesicles has an impact on the PERP, which could explain our results. In this study we investigated the role of PRL in the PERP of two different strains of

mice that belong to the two main subspecies of house mouse, _Mus musculus musculus_ (PWK) and _Mus musculus domesticus_ (BL6), for three main reasons. As already presented, the two strains

have very different PERP duration, widening the dynamic range of this behavioral parameter and increasing the probability of detecting an effect of the manipulations. Second, in addition to

differences in PERP duration, BL6 and PWK males have very different sexual performance, reflected in several behavioral parameters as, for example, the number of mounts needed to reach

ejaculation. Despite the differences (which were not explored as they are outside the scope of the present study), the effects of the pharmacological manipulations were similar across the

two strains, causing either no effect or changing the behavior in the same direction (shorter latency to start mounting the female in bromocriptine-treated males). This is an important point

that strengthens our conclusions. Finally, although fundamental for many present-day discoveries, the usage of the common inbred strains of mice comes at a cost, due to the limitations in

their genetic background that sometimes leads to results that are specific to the strain of mouse used59,60,61. Wild-derived strains of mice are valuable tools that can complement the

genetic deficiencies of classical laboratories strains of mice45,62. Despite the fact that larger numbers of animals are used (because experiments are repeated on each mouse strain), this

approach is already routinely used in other fields, such as in immunological studies63, providing greater confidence to the results obtained from the effect of pharmacological manipulations

on behavior, for example. As initially discussed, PRL can affect peripheral and central pathways that have been implicated in sexual performance and motivation. Even though our manipulations

indiscriminately affect both, our results refute the idea that PRL decreases sexual activity, the hallmark of the PERP. What could be the role of copulatory PRL? PRL release may be the

“side-effect” of the neuromodulatory changes that occur during sexual behavior; this is merely the result of reduction in DA levels (DA inhibits PRL release) and/or the increase in oxytocin

and serotonin (known stimulating factors of PRL release) instead of having the principal role in the establishment of PERP64,65,66. The fact that PRL levels are already elevated during

sexual interaction in BL6 and PWK males further suggests that PRL cannot promote by itself reduced sexual activity, at least in male mice. Other studies point towards a role of PRL in the

establishment of parental behavior67,68,69. New behavioral paradigms will be fundamental in unraveling this mystery. METHODS ANIMALS BL6 (_Mus musclus domesticus_, C57BL/6J) and Wild (_Mus

musculus musculus_, PWD/PhJ and PWK/PhJ) mice were ordered from The Jackson Laboratories and maintained in our animal facility. Animals were weaned at 21 days and housed in same-sex groups

in stand-alone cages (1284L, Techniplast, 365 × 207 × 140 mm) with access to food and water ad libitum. Mice were maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle and experiments were performed

during the dark phase of the cycle, under red dim light. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Users Committee of the Champalimaud Neuroscience Program and the Portuguese

National Authority for Animal Health (Direcção Geral de Veterinária). Females were kept house grouped and males were isolated before the sexual training. Both males and females were sexually

experienced and habituated to be handled and to the assay routine. To enter the study, a male had to ejaculate three times (in four sessions). Males interacted with different females in

each sexual encounter. Each manipulation was performed in a different group of males and, within each manipulation, experiments were conducted in parallel for both BL6 and PWK. Trials were

conducted in the male home cage (1145T, Techniplast, 369 × 156 × 132 mm) stripped from nesting, food, and water: covered with a transparent acrylic lid. The trial started with the entry of

the female in the setup (_t_ = 0 min). OVARIECTOMY AND HORMONAL PRIMING All females underwent bilateral ovariectomy under isoflurane anesthesia (1–2% at 1 L/min). After exposing the muscle

with one small dorsal incision (1 cm), a small incision was made in the muscle wall, at the ovary level, on each side. The ovarian arteries were cauterized and both ovaries were removed. The

skin was sutured, and the suture topped with iodine and wound powder. The animals received an i.p. injection of carpofen before being housed individually with food supplemented with

analgesic (MediGel, 1 mg carprofen/2 oz cup) for 2 days recovery and then re-grouped in their home cages. Female mice were primed subcutaneously 48 h before the assay with 0.1 ml estrogen (1

mg/ml, Sigma E815 in sesame oil) and 4 h before the assay with 0.1 ml progesterone (5 mg/ml, Sigma 088K0671 in sesame oil). BLOOD COLLECTION Tail-tip whole-blood samples were collected from

the male tail, immediately diluted in PBS-T (PBS, 0.05% Tween-20), and frozen at –20 °C where it was stored until use46. To profile [PRL]blood during sexual behavior (Fig. 1a), baseline

blood was collected 30 min before (_t_ = −30 min) the female entry (_t_ = 0 min). From this point on, blood collection was locked to the onset of specific behaviors: once the male did the

first MA, after executing a fixed number of mounts (Mx) and after ejaculation (after the male exhibited the stereotypical shivering, falling to the side and decoupling from the female). We

choose Mx = 5 for BL6 and Mx = 3 for PWK to ensure that the males would have sufficient sexual interaction without reaching ejaculation. Contrarily to PWK males that, in the presence of a

receptive female, the majority engages in sexual behavior, BL6 do not. Thus, after 30 min interacting with the female without displaying sexual interest, we collected a blood sample and

terminated the trail (Fig. 1b, social). Because blood collection is an invasive procedure and PRL is also released under stress, we evaluated if the manipulation itself could induce PRL

release. For that we collected blood every 20 min for 1 h from males resting in their home cage (Fig. 1c). Domperidone is a D2 dopamine receptor antagonist that was previously used to study

the inhibitory tone of dopamine on PRL release from the pituitary, inducing a PRL peak 15 min after i.p. injection46. To test the magnitude of the PRL release of the two mouse strains under

domperidone (Fig. 2a), we conducted a pilot study where we collected a blood sample before (baseline) and 15 min after Domp injection (20 mg/kg; Abcam Biochemicals). We opted to manipulate

[PRL]blood through domperidone instead of injecting PRL directly to induce a PRL release similarly to a natural occurring instead of adding a recombinant form. Bromocriptine is a D2 dopamine

receptor agonist known to inhibit endogenous prolactin release34. To test its efficacy on blocking PRL release during sexual behavior (Fig. 3a), we conducted a second pilot study where the

males were injected (100 µg bromo or vehicle) 2 h before the trial started. Blood samples were collected just before injection, 1 h after injection and after ejaculation. PROLACTIN

QUANTIFICATION [PRL]blood quantification was done as previously described46. Briefly, a 96-well plate (Sigma-Aldrich cls 9018-100EA) was coated with 50 µl capture antibody anti-rat PRL

(anti-rPRL-IC) (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), AFP65191 (Guinea Pig), NIDDK-National Hormone and Pituitary Program (NHPP, TORRANCE, CA) at a final

dilution of 1:1000 in PBS of the antibody stock solution, reconstituted in PBS as described in the datasheet (Na2HPO4 7.6 mM; NaH2PO4 2.7 mM; and NaCl 0.15 M; pH 7.4). The plate was

protected with Parafilm® and incubated at 4 °C overnight in a humidified chamber. The coating antibody was decanted and 200 µl of blocking buffer (5% skimmed milk powder in PBS-T) was added

to each well to block nonspecific binding. The plate was left for 2 h at room temperature on a microplate shaker. In parallel, a standard curve was prepared using a twofold serial dilution

of Recombinant mouse Prolactin (mPRL; AFP-405C, NIDDK-NHPP) in PBS-T with BSA 0.2 mg/ml (bovine serum albumin; Millipore 82-045-1). After the blocking step, the plate was washed (three times

for 3 min at room temperature with PBS-T), 50 µl of quality control (QC), standards or samples were loaded in duplicate into the wells, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature on the

microplate shaker. The plate was washed, and the complex was incubated for another 90 min with 50 µl detection antibody (rabbit alpha mouse PRL, a gift from Patrice Mollard Lab) at a final

dilution of 1:50,000 in blocking buffer solution. Following a final wash, this complex was incubated for 90 min with 50 µl horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (anti-rabbit, IgG,

Fisher Scientific; NA934) diluted in 50% PBS and 50% blocking buffer. One tablet of _O_-phenylenediamine (Life Technologies SAS 00-2003) was diluted into 12 ml citrate-phosphate buffer pH 5,

containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide. One hundred microliters of this substrate solution was added to each well (protected from light), and the reaction was stopped after 30 min with 50 µl of

3 M HCl. The optical density from each well was determined at 490 nm using a microplate reader (SPECTROstarNano, BMG LABTECH). An absorbance at 650 nm was used for background correction. A

linear regression was used to fit the optical densities of the standard curve vs their concentration using samples ranging from 0.1172 to 1.875 ng/ml, using the former as the lower limit of

detection. Appropriate sample dilutions were carried out in order to maintain detection in the linear part of the standard curve, and PRL concentrations were extrapolated from the OD of each

sample. To control for reproducibility of the assay, trunk blood of males injected with domperidone was immediately diluted in PBS-T and pulled to be used as QC. Loading of the wells was

done vertically left to right and QC was always loaded on the top row. The formula OD (Co, _t_) = OD (Ob) + _α_ (QC)._t_ was used to correct the ODs for loading dwell time (OD: optical

density, Co: corrected, _t_: well number, Ob: observed, _α_: QC linear regression’ _α_). Coefficient of variability was kept to a maximum of 10%. BEHAVIORAL ASSAYS Each male underwent two

trials: one with vehicle and one with drug (domperidone or bromocriptine). Administrations were counterbalanced between animals and spaced 7 days. In the first assay, for pharmacological

induction of acute PRL release (Fig. 2b), the male was injected i.p. with domperidone or vehicle 15 min before the trial started (_t_ = −15 min). Animals were allowed to interact until the

male reached ejaculation or 1 h in the case the male did not display sexual behavior. Conversely, for pharmacological blockage of PRL release (Fig. 3b), a second group of males were

pre-treated with bromocriptine or vehicle with a subcutaneous injection 2 h before the beginning of the trial (_t_ = −120 min). Animals were allowed to interact until a maximum of 2 h after

the male reached ejaculation or 1 h in the case the male did not display sexual behavior. For the BL6 unmanipulated group, the female was added to the male home cage without disturbing the

male (Supplementary Data 1). Animals were allowed to interact until the male reached ejaculation or 1 h in the case the male did not display sexual behavior. BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS The behavior

was recorded from the top and side with pointgrey cameras (FL3- U3-13S2C-CS) connected to a computer running a custom Bonsai software70. Behavior was manually annotated using the open source

program Python Video Annotator (https://pythonvideoannotator.readthedocs.io) and analyzed using Matlab. The number of MA (mount without intromission), mounts (mounts with intromission),

latency to mount (first MA or mount), latency to ejaculation and PERP (latency between ejaculation and the next mount) was calculated. Total number of mounts (TM) was calculated as the sum

of MA and mounts and TM rate was calculated as TM/latency to ejaculate. The percentage of animals that reached ejaculation and regain sexual activity under 2 h (refractory period) were also

calculated. The modulation index (MI) was calculated as (_X_drug − _X_vehicle)/(_X_drug + _X_vehicle). The centroid position and individual identity of each pair was followed offline using

the open source program idtracker.ai71 and used to calculate male velocity and interindividual distance with Matlab (Supplementary Data 3). STATISTICAL ANALYSIS The statistical details of

each experiment, including the statistical tests used and exact value of _n_, are detailed in each figure legend. Comparisons were always performed within the same strain and not across

strains. Data related to prolactin quantification were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 software and presented as mean ± SD. For comparison within strain (Fig. 1a, c) an RM one-way Anova

followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used. Comparison of paired samples comparing two groups, statistical analysis was performed by using a paired-sample two-tailed _t_-test

(Figs. 1b and 2a baseline-Domp). For the effect of treatment (veh or bromo) and time of sampling (B1, B2, and Ejac) (Fig. 3a) an RM two-way Anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test

was used. Data related to animal behavior were analyzed with MATLAB R2019b and presented as median ± MAD (median absolute deviation with standard scale factor). Animals were randomized

between treatments and comparison between the two conditions were done with Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Figs. 2d–f and 3e–h and Supplementary Data 2–4). Only animals that ejaculated in both

sessions were included in the statistical analysis (Domperidone: _n_BL6 = 7, _n_PWK = 13; bromocriptine: _n_BL6 = 10, _n_PWK = 13). Significance was accepted at _P_ < 0.05 for all tests.

REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated to support the

findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Masters, W. H. & Johnson, V. E. _Human Sexual Response_ (Bantam Books, New York,

1966). * Seizert, C. A. The neurobiology of the male sexual refractory period. _Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev._ 92, 350–377 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Levin, R. J. Revisiting

post‐ejaculation refractory time—what we know and what we do not know in males and in females. _J. Sex. Med._ 6, 2376–2389 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * McGill, T. E. Sexual

behavior of the mouse after long-term and short-term postejaculatory recovery periods. _J. Genet. Psychol._ 103, 53–57 (1963). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rodriguez-Manzo, G.

Blockade of the establishment of the sexual inhibition resulting from sexual exhaustion by the Coolidge effect. _Behav. Brain Res._ 100, 245–254 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Wilson, J. R., Kuehn, R. E. & Beach, F. A. Modification in the sexual behavior of male rats produced by changing the stimulus female. _J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol._ 56, 636 (1963).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rojas-Durán, F. et al. Correlation of prolactin levels and PRL-receptor expression with Stat and Mapk cell signaling in the prostate of long-term

sexually active rats. _Physiol. Behav._ 138, 188–192 (2015). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hernandez, M. E. et al. Prostate response to prolactin in sexually active male rats.

_Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol._ 4, 28 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Kruger, T. H. C., Haake, P., Hartmann, U., Schedlowski, M. & Exton, M. S. Orgasm-induced

prolactin secretion: feedback control of sexual drive? _Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev._ 26, 31–44 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Drago, F. Prolactin and sexual behavior: a

review. _Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev._ 8, 433–439 (1984). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Freeman, M. E., Kanyicska, B., Lerant, A. & Nagy, G. Prolactin: structure, function, and

regulation of secretion. _Physiol. Rev._ 80, 1523–1631 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grattan, D. R. & Kokay, I. C. Prolactin: a pleiotropic neuroendocrine hormone. _J.

Neuroendocrinol._ 20, 752–763 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brody, S. & Krüger, T. H. C. The post-orgasmic prolactin increase following intercourse is greater than

following masturbation and suggests greater satiety. _Biol. Psychol._ 71, 312–315 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Egli, M., Leeners, B. & Kruger, T. H. C. Prolactin secretion

patterns: basic mechanisms and clinical implications for reproduction. _Reprod. Camb. Engl._ 140, 643–654 (2010). CAS Google Scholar * Exton, M. S. et al. Coitus-induced orgasm stimulates

prolactin secretion in healthy subjects. _Psychoneuroendocrinology_ 26, 287–294 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Exton, N. G. et al. Neuroendocrine response to film-induced

sexual arousal in men and women. _Psychoneuroendocrinology_ 25, 187–199 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Krüger, T. et al. Neuroendocrine and cardiovascular response to sexual

arousal and orgasm in men. _Psychoneuroendocrinolgy_ 23, 401–411 (1998). Article Google Scholar * Krüger, T. H. C. et al. Serial neurochemical measurement of cerebrospinal fluid during

the human sexual response cycle. _Eur. J. Neurosci._ 24, 3445–3452 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Exton, M. S. et al. Cardiovascular and endocrine alterations after

masturbation-induced orgasm in women. _Psychosom. Med_. 61, 280–289 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kruger, T. et al. Specificity of the neuroendocrine response to orgasm

during sexual arousal in men. _J. Endocrinol._ 177, 57–64 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Oaknin, S., Castillo, A. R. D., Guerra, M., Battaner, E. & Mas, M. Changes in

forebrain Na,K-ATPase activity and serum hormone levels during sexual behavior in male rats. _Physiol. Behav._ 45, 407–410 (1989). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Haake, P. et al.

Absence of orgasm-induced prolactin secretion in a healthy multi-orgasmic male subject. _Int J. Impot. Res._ 14, 3900823 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Svare, B. et al.

Hyperprolactinemia suppresses copulatory behavior in male rats and mice. _Biol. Reprod._ 21, 529–535 (1979). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buvat, J. Hyperprolactinemia and sexual

function in men: a short review. _Int. J. Impot. Res._ 15, 3901043 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sato, F. et al. Suppressive effects of chronic hyperprolactinemia on penile

erection and yawning following administration of apomorphine to pituitary‐transplanted rats. _J. Androl._ 18, 21–25 (1997). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Melmed, S. et al. Diagnosis and

treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. _J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab._ 96, 273–288 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grattan, D. R.

& Bridges, R. S. in _Hormones, Brain and Behavior_ 2nd edn, 2471–2504 (Academic Press, 2009). * Riddle, O., Bates, R. W. & Dykshorn, S. W. The preparation, identification and assay

of prolactin—a hormone of the anterior pituitary. _Am. J. Physiol._ 105, 191–216 (1933). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nagano, M. & Kelly, P. A. Tissue distribution and regulation of

rat prolactin receptor gene expression. Quantitative analysis by polymerase chain reaction. _J. Biol. Chem._ 269, 13337–13345 (1994). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Aoki, M. et al.

Widespread cell-specific prolactin receptor expression in multiple murine organs. _Endocrinology_ 160, 2587–2599 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Aoki, H. et al. Suppression

by prolactin of the electrically induced erectile response through its direct effect on the corpus cavernosum penis in the dog. _J. Urol._ 154, 595–600 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Ganong, W. F. Circumventricular organs: definition and role in the regulation of endocrine and autonomic function. _Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol._ 27, 422–427 (2000). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grattan, D. R. et al. Feedback regulation of PRL secretion is mediated by the transcription factor, signal transducer, and activator of transcription 5b.

_Endocrinology_ 142, 3935–3940 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brown, R. S. E., Kokay, I. C., Herbison, A. E. & Grattan, D. R. Distribution of prolactin‐responsive

neurons in the mouse forebrain. _J. Comp. Neurol._ 518, 92–102 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kirk, S. E., Grattan, D. R. & Bunn, S. J. The median eminence detects and

responds to circulating prolactin in the male mouse. _J. Neuroendocrinol._ 31, e12733 (2019). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Georgescu, T., Ladyman, S. R., Brown, R. S. E. &

Grattan, D. R. Acute effects of prolactin on hypothalamic prolactin receptor expressing neurones in the mouse. _J. Neuroendocrinol._ 32, e12908 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Bole-Feysot, C., Goffin, V., Edery, M., Binart, N. & Kelly, P. A. Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor

knockout mice. _Endocr. Rev._ 19, 225–268 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Corona, G., Jannini, E. A., Vignozzi, L., Rastrelli, G. & Maggi, M. The hormonal control of

ejaculation. _Nat. Rev. Urol._ 9, 508 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Levin, R. Is prolactin the biological “off switch” for human sexual arousal? _Sex. Relatsh. Ther._ 18,

237–243 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Turley, K. R. & Rowland, D. L. Evolving ideas about the male refractory period. _Bju Int_. 112, 442–452 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Kamel, F., Right, W. W., Mock, E. J. & Frankel, A. I. The influence of mating and related stimuli on plasma levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, prolactin,

and testosterone in the male rat 1. _Endocrinology_ 101, 421–429 (1977). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kamel, F. & Frankel, A. J. Hormone release during mating in the male rat:

time course, relation to sexual behavior, and interaction with handling procedures. _Endocrinology_ 103, 2172–2179 (1978). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kruger, T. et al. Effects

of acute prolactin manipulation on sexual drive and function in males. _J. Endocrinol._ 179, 357–365 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lenschow, C. & Lima, S. Q. In the

mood for sex: neural circuits for reproduction. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 60, 155–168 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gregorová, S. & Forejt, J. PWD/Ph and PWK/Ph inbred

mouse strains of _Mus m. musculus_ subspecies—a valuable resource of phenotypic variations and genomic polymorphisms. _Folia Biol. Prague_ 46, 31–41 (2000). Google Scholar * Guillou, A. et

al. Assessment of lactotroph axis functionality in mice: longitudinal monitoring of PRL secretion by ultrasensitive-ELISA. _Endocrinology_ 156, 1924–1930 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Gala, R. R. The physiology and mechanisms of the stress-induced changes in prolactin secretion in the rat. _Life Sci._ 46, 1407–1420 (1990). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Lyons, D. J. & Broberger, C. TIDAL WAVES: network mechanisms in the neuroendocrine control of prolactin release. _Front. Neuroendocr._ 35, 420–438 (2014). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Grattan, D. R. 60 years of neuroendocrinology: The hypothalamo-prolactin axis. _J. Endocrinol._ 226, T101–T122 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Cocchi, D. et al. Prolactin-releasing effect of a novel anti-dopaminergic drug, domperidone, in the rat. _Neuroendocrinology_ 30, 65–69 (1980). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Costall, B., Fortune, D. H. & Naylor, R. J. Neuropharmacological studies on the neuroleptic potential of domperidone (R33812). _J. Pharm. Pharmacol._ 31, 344–347 (1979). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Molik, E. & Błasiak, M. The role of melatonin and bromocriptine in the regulation of prolactin secretion in animals—a review. _Ann. Anim. Sci._ 15, 849–860

(2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Krüger, T. H. C., Hartmann, U. & Schedlowski, M. Prolactinergic and dopaminergic mechanisms underlying sexual arousal and orgasm in humans. _World

J. Urol._ 23, 130–138 (2005). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Bronson, F. H. & Desjardins, C. Endocrine responses to sexual arousal in male mice. _Endocrinology_ 111, 1286–1291

(1982). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pfaus, J. G. Pathways of sexual desire. _J. Sex. Med._ 6, 1506–1533 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pfaus, J. G. &

Phillips, A. G. Role of dopamine in anticipatory and consummatory aspects of sexual behavior in the male rat. _Behav. Neurosci._ 105, 727–743 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Hull, E. M., Muschamp, J. W. & Sato, S. Dopamine and serotonin: influences on male sexual behavior. _Physiol. Behav._ 83, 291–307 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hyun,

J.-S. et al. Localization of peripheral dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in rat and human seminal vesicles. _J. Androl._ 23, 114–120 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

puglisi-Allegra, S. & Cabib, S. Psychopharmacology of dopamine: the contribution of comparative studies in inbred strains of mice. _Prog. Neurobiol._ 51, 637–661 (1997). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Cabib, S., Puglisi-Allegra, S. & Ventura, R. The contribution of comparative studies in inbred strains of mice to the understanding of the hyperactive

phenotype. _Behav. Brain Res_. 130, 103–109 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Welker, E. & Loos, H. Vder Quantitative correlation between barrel-field size and the sensory

innervation of the whiskerpad: a comparative study in six strains of mice bred for different patterns of mystacial vibrissae. _J. Neurosci._ 6, 3355–3373 (1986). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Fernandes, C. et al. Behavioral characterization of wild derived male mice (Mus musculus musculus) of the PWD/Ph inbred strain: high exploration compared to

C57BL/6J. _Behav. Genet._ 34, 621–630 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Deschepper, C. F., Olson, J. L., Otis, M. & Gallo-Payet, N. Characterization of blood pressure and

morphological traits in cardiovascular-related organs in 13 different inbred mouse strains. _J. Appl. Physiol._ 97, 369–376 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * McIntosh, T. K. &

Barfield, R. J. Brain monoaminergic control of male reproductive behavior. I. Serotonin and the post-ejaculatory refractory period. _Behav. Brain Res._ 12, 255–265 (1984). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * McIntosh, T. K. & Barfield, R. J. Brain monoaminergic control of male reproductive behavior. II. Dopamine and the post-ejaculatory refractory period. _Behav.

Brain Res._ 12, 267–273 (1984). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Carmichael, M. S. et al. Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. _J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab._ 64,

27–31 (1987). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brown, R. E. Hormones and paternal behavior in vertebrates. _Am. Zool._ 25, 895–910 (1985). Article CAS Google Scholar * Schradin, C.

& Anzenberger, G. Prolactin, the hormone of paternity. _Physiology_ 14, 223–231 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Stagkourakis, S. et al. A neuro-hormonal circuit for paternal

behavior controlled by a hypothalamic network oscillation. _Cell_ 182, 960–975.e15 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lopes, G. et al. Bonsai: an event-based

framework for processing and controlling data streams. _Front. Neuroinformatics_ 9, 7 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Romero-Ferrero, F., Bergomi, M. G., Hinz, R. C., Heras, F. J. H.

& Polavieja, G. Gde idtracker.ai: tracking all individuals in small or large collectives of unmarked animals. _Nat. Methods_ 16, 179–182 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Patrice Mollard and his team for welcoming S.V. in their facilities, teaching the uElisa technique, and for providing antibodies. We also

express our gratitude to Francisco Romero for all the support with IdTracker, Gil Costa for the figure design, the Champalimaud Vivarium for their support with the wild derived animals, and

the whole Lima lab for critical input. This work was supported by the Champalimaud Foundation, UIDB/04443/2020, LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022170, LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022231, ERC Consolidator

Grant (772827, to S.Q.L.), Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia SFRH/BD/51011/2010 (to S.V.), and PhRMA Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship in Informatics (to T.M.). AUTHOR INFORMATION

AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown, Av. Brasilia, s/n Lisboa, Portugal Susana Valente & Susana Q. Lima * Graduate Program in Areas of

Basic and Applied Biology (GABBA), University of Porto, 4200-465, Porto, Portugal Susana Valente * Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA Tiago Marques *

McGovern Institute for Brain Research, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA Tiago Marques * Center for Brains, Minds and Machines, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA Tiago Marques Authors * Susana

Valente View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tiago Marques View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Susana Q. Lima View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.Q.L. and S.V. designed the study. S.V. performed the

experiments, annotation of the behavior, and IdTracker. T.M. wrote the Matlab code. S.V. analyzed the data with input from S.Q.L. and T.M. S.Q.L. and S.V. wrote the paper with contributions

from others. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Susana Q. Lima. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S

NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE DESCRIPTION OF

ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Valente, S., Marques, T. & Lima, S.Q. No evidence for prolactin’s involvement

in the post-ejaculatory refractory period. _Commun Biol_ 4, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01570-4 Download citation * Received: 18 August 2020 * Accepted: 04 December 2020 *

Published: 04 January 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01570-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative