2D graphene oxide–aptamer conjugate materials for cancer diagnosis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Download PDF Review Article Open access Published: 17 February 2021 2D graphene oxide–aptamer conjugate materials for cancer diagnosis Simranjeet Singh Sekhon ORCID:

orcid.org/0000-0001-9811-51961, Prabhsharan Kaur2, Yang-Hoon Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3406-48681 & …Satpal Singh Sekhon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4490-14713,4 Show authors npj 2D

Materials and Applications volume 5, Article number: 21 (2021) Cite this article

10k Accesses

71 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Subjects Biomedical materialsBiosensors Abstract2D graphene oxide (GO) with large surface area, multivalent structure can easily bind single-stranded DNA/RNA (aptamers) through hydrophobic/π-stacking interactions, whereas aptamers having

small size, excellent chemical stability and low immunogenicity bind to their targets with high affinity and specificity. GO–aptamer conjugate materials synthesized by integrating aptamers

with GO can thus provide a better alternative to antibody-based strategies for cancer diagnostic and therapy. Moreover, GO’s excellent fluorescence quenching properties can be utilized to

develop efficient fluorescence-sensing platforms. In this review, recent advances in GO–aptamer conjugate materials for the detection of major cancer biomarkers have been discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others Label-free electrochemical biosensor based on green-synthesized reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4/nafion/polyaniline for ultrasensitive detection of SKBR3

cell line of HER2 breast cancer biomarker Article Open access 24 May 2024 Integrating gold nanoclusters, folic acid and reduced graphene oxide for nanosensing of glutathione based on

“turn-off” fluorescence Article Open access 27 January 2021 Ultrasensitive and label free electrochemical immunosensor for detection of ROR1 as an oncofetal biomarker using gold

nanoparticles assisted LDH/rGO nanocomposite Article Open access 21 July 2021 Introduction

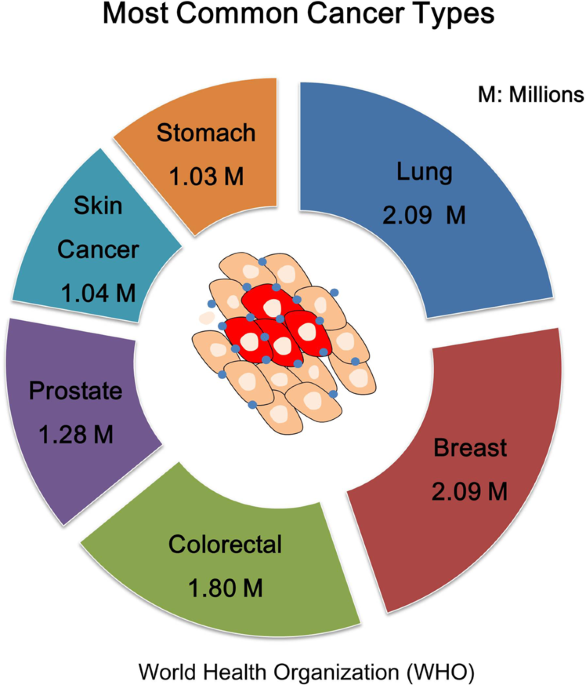

Cancer is a very fatal disease that resulted in ~9.6 million deaths worldwide in 2018 (World Health Organization) (Fig. 1). Cancer detection at an initial stage and its timely treatment are

essential to improve the survival rate of cancer patients1. An early identification of cancer helps in better response to an effective treatment and can lead to a higher probability of

survival, less morbidity, and affordable treatment. Hence, the development of sensitive, specific, fast, and economical methods is important for an early diagnosis of cancer2. The current

cancer diagnosis techniques, including mammography, level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in blood, Papanicolaou test, occult blood analysis, endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scan,

X-ray, ultrasound imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging are unsuitable for detecting specific cancers at the initial stage. In addition, some of these methods are expensive and not

available universally. Thus, there is a strong demand to develop highly specific and reliable techniques that are suitable for the timely detection of different cancer biomarkers3.

Fig.1: Cancer types and number of patients.

Cancer, a leading cause of death worldwide accounted for an estimated 9.6 million deaths in 2018. The most common types of cancer and the number of affected patients are mentioned. (Source:

World Health Organization (WHO)).

Full size imageThe infection and development of diseases generally involve the production or a change in the level of some biomolecules present in the human body, and suitable disease biomarkers can be

employed for the detection as well as monitoring of the disease. The biological state in cancer progression can be determined by cancer biomarkers and it helps in understanding the cellular

processes of cancer cells. The collection of samples from various body fluids (viz. urine, blood, saliva, tears, or sweat) is quite simple and less invasive, and the samples can be collected

at any time for monitoring the disease. Hence, there is a potential for the development of effective techniques for speedy diagnosis and treatment of cancer4. The detection of biomarkers in

body fluids is, however, a challenging task because of its low concentration and complex biological assays. During this period, the advent of nanotechnology with applications in almost all

branches of science has provided a new direction for the potential use of various nanomaterials for cancer theragnosis5,6,7,8.

In this respect, various carbon nanomaterials with suitable properties have resulted in innovative strategies for the development of biosensors. Another advantage of using nanomaterials is

that their properties can be easily controlled by functionalizing with suitable bio-functional groups that can result in the creation of several binding sites, which can help in capturing

different biomolecules and immobilization of biomarker capture antibodies9. Out of various carbon nanomaterials, two-dimensional (2D) graphene-based materials (graphene, graphene oxide (GO),

and reduced GO (rGO)) (Fig. 2) have been widely used for improving the performance of sensors owing to their excellent properties10,11. Graphene is typically hydrophobic, chemically inert,

and biocompatible. It can adsorb various biomolecules via π–π stacking interactions between the hexagonal cells and the carbon rings prevalent in most carbon nanomaterials and is thus used

in biosensors12. Graphene-based biosensors can be very beneficial for the detection of cancer biomolecules overexpressed on the cancerous cell surface13.

Fig. 2: Graphene oxide.The structure, properties, and applications of graphene oxide.

Full size imageSome of the current methods (centrifugation, chromatography, fluorescence, and magnetic-activated cell sorting) used for cancer diagnosis are highly dependent on the expertise and subjective

judgment of the operator, whereas some other methods, such as CT scan, based on cross-sectional imaging and biopsy are very expensive, time-consuming, and inconvenient for patients, and

hence are not suitable for an early diagnosis of cancer. The diagnostic techniques that recognize the symptoms, understand the working of normal cells as to how they become cancerous, are

crucial for the detection and treatment of cancer at an initial stage. For targeting cancer cells, aptamers can be used as probes in place of antibodies, as they consist of single-stranded

oligonucleotides (DNA, RNA) generated from large random pools of sequences that can bind to their targets with high specificity. Their properties, such as high stability, resistance to harsh

conditions, reversible denaturation, low toxicity, immunogenicity, and oriented surface immobilization are extremely effective for targeting cancer cells14,15. The desirable properties of

both carbon nanomaterials and aptamers can be exploited by functionalizing nanomaterials with aptamers and the resulting conjugate materials can provide a very sensitive and efficient

biosensing system with target-specific imaging and suitable therapy16,17,18,19. In this context, aptamer-based biosensors (aptasensors) can provide an alternative strategy for label-free

detection of cancer cells as these are rapid (seconds to minutes), sensitive (detection at sub-picomolar to micromolar concentrations), and also reagent-less.

The present review focuses on the recent trends as applicable in the use of 2D GO–aptamer conjugate materials for the detection of main types of cancer biomarkers. The selection process of

aptamers and their suitability as a replacement for antibodies in cancer diagnosis has been explained. Functionalization of GO with aptamers resulting in the formation of conjugate materials

that are effectively used in cancer diagnosis and sensing platforms have been reviewed here. The review also highlights the use of excellent fluorescence quenching properties of GO in

sensing for cancer diagnosis. Finally, the critical discussion, challenges faced by the scientific community, and possible future directions for the development of 2D materials based on

aptamer-functionalized GO for cancer diagnosis have also been discussed.

AptamersAptamers as an alternative to antibodiesAptamers can bind to a given target with very high specificity and affinity, and is similar to the binding of antibodies to antigens20,21. At present, antibodies are commonly used as

molecular recognition agents in a large number of applications. Antibody-based devices, however, cannot be easily deployed under field conditions, as specific temperature range, relative

humidity, and ionic strength of the buffer solution are required to retain their functionality. The drawbacks of antibodies, however, can be addressed by using aptamers, in place of

antibodies (Table 1), as they can be directly selected in vitro against different targets22. Aptamers are selective and sensitive like antibodies and, in addition, they are highly stable

over a wide range of temperature, relative humidity, and ionic concentration values. The use of aptamers does not trigger an immune response and they are relatively smaller in size that

leads to fast tissue penetration. This, along with their low-cost synthesis and high stability, can be used to generate multiple aptamers against different targets, such as small molecules,

proteins, intact viruses, and even cells23. Thus, aptamers can be future molecular probes for an accurate and specific detection, as well as for cancer therapy14,24. Cancer-specific markers

can be specifically recognized using aptamers by targeting proteins overexpressed in tumors. The use of aptamers in cancer research can lead to significant advances in cancer detection,

diagnosis, and target therapy25. A number of aptamers selected against various targets have already been reported and show good performance in diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic tools

in cancer treatment. In addition, aptamers along with nanoparticle technology can also be employed in cancer medicine for enriching rare cancer cells26,27. Aptamers can be easily

functionalized multiple times within their backbone or at the termini with a number of functional groups for diagnostic and therapeutic objectives, without any compromise in their

activity.

Table 1 Aptamers as an alternative to antibodies: comparison.Full size tableThus, aptamers can mimic antibodies by folding into complex three-dimensional structures that bind to specific targets. However, their easy synthesis, low-cost, low immunogenicity, and low

variability empower them as an ideal alternative to antibodies.

Selection and generation of aptamersAptamers are generally isolated from randomized pools of RNA by Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) process, reported in 1990 by three research groups

simultaneously28,29. SELEX is an evolutionary in vitro iterative technique used for the selection of aptamers that can specifically identify targets ranging from large proteins to small

molecules. A general repetitive procedure of partitioning and amplification for the selection of aptamers during the SELEX is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3: Selection of aptamers.Schematic representation of aptamer generation by SELEX and cell-SELEX.

Full size imageThe traditional SELEX is initiated by the use of a random library of ~1015 sequences, having a typical length of 20–100 nucleotides flanked by primer sequences of fixed length for the

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification30. Nucleotides that can bind different target molecules with large affinity and high specificity are then selected. The aptamer library is first

converted into single-stranded oligonucleotides, which are made up of regions of random sequences, normally containing 30–40 mers with primer binding sites on sides. The library components

bound to the target are then separated from the unbound ones to remove any unwanted nonspecific components. The PCR amplification of the library components bound to the target results in the

creation of another library, which is then used in the next round of selection31. The newly generated pool of nucleic acids then serves as the starting point for the next SELEX cycle. This

procedure is repeated continuously until a highly enriched pool is obtained for sequences that can specifically recognize the target. The cloning and sequencing of PCR products are carried

out after the last optimal round of aptamer selection.

Although various modifications have been made to the selection process for more specific, efficient, and fast generation of aptamers, yet cell-SELEX is most suited for the detection of

cancer32,33,34,35. The fundamental difference between cell-SELEX and the commonly used SELEX is in the use of whole living cells as targets (Fig. 3). The counter selection step is very

crucial as it reduces the oligonucleotides that bind nonspecifically or those that bind common molecules present on the surface of both types of cells and hence result in an increase in the

specificity of the enriched pool to the target cells. After each round, a binding assay of the enriched pool to control and target cells is conducted to check the extent of aptamer

enrichment. A main advantage of cell-SELEX is its ability to create aptamers against a particular type of cell, even if the cell markers are unknown. An increase in the level of some of

these markers is generally observed in a diseased state, such as cancer, and modifications can be made to derive entirely new markers on the cell surface that can distinguish between the

normal and diseased cells. Although additional counter selection steps are required to avoid the selection of nonspecific aptamers, yet once selected, the resulting aptamers are very useful

for detection, therapy, and targeted drug delivery14,27,36,37. Cell-SELEX is preferred for the selection of specific aptamers for tumor cell detection and therapeutic purposes. However,

cell-SELEX still has certain technological limitations, such as cell conditions and the complex nature of some cancer cell lines. The evasion of nonspecific uptake during aptamer selection

favors the identification of specific aptamers, and hence the choice of proper cell line is very crucial in order to improve aptamer specificity.

Thus, aptamers are oligonucleotides that can be easily integrated with other technologies involving nucleic acid-based systems. Their small size increases the accessibility to most

biological areas that are beyond the reach of antibodies. The real significance of aptamers lies in the ease by which they can be engineered into biosensors and other devices that are often

vital to emerging technologies.

2D GOGraphene-based materialsA. Geim and K. Novoselov discovered graphene by peeling off the atomically thin layers from the chunks of graphite, using the sticky tape method38. Since then, this material has

revolutionized the scientific world as it has applications in almost all branches of science. Based on its material properties, graphene was earlier described as one of the strongest,

thinnest, and lightest material that is usually true at the atomic level, although it may behave differently at the micro level39. 2D graphene is a thin layer of carbon atoms forming a

honeycomb pattern. The carbon atoms are so tightly arranged that not even helium atoms can move across them. The large surface area (2600 m2 g−1) of 2D graphene that arises from the

symmetric arrangement of C–C bonds is also desirable for many of its applications. Graphene is a hydrophobic material that is stable in air up to 200 °C and is insoluble in organic solvents

but prone to aggregate in an aqueous solution.

Another major advantage of graphene is that its characteristics can be modified, by attaching suitable functional groups via chemical functionalization. In fact, this is the first step

commonly followed for the potential use of graphene-based materials in various applications. The chemical modification of graphene by functionalization widens their scope of applications,

specifically for the electronic devices. The functionalization occurs on its p surface or at the edges, via π–π interactions or the electron transfer processes. Graphene may have defects

along the C–C bond network due to the missing of one or more sp2-bonded carbon atoms constituting the network or the availability of atoms with sp3 hybridization40. It enhances the chemical

reactivity of graphene as the carbon atoms in the vicinity of a defect are chemically activated and exhibit a different electronic structure41.

Graphene sheets consist of 2D layers formed by sp2-hybridized C–C bonds in its structure (Fig. 4). The optical and electrical properties of graphene are affected by the presence of defects

and also the method of synthesis42. GO is an electrical insulator and, in addition, is also chemically heterogeneous, containing a large number of oxygen groups attached to the carbon

lattice, resulting in defect regions. Thus, it is suitable for use in optical sensors due to its optical sensing properties, photoluminescence, and being a highly efficient fluorescence

quencher. The optoelectronic properties of GO can be modified by employing various chemical, electrochemical, and thermal routes. rGO has a high degree of defects and oxygen content on its

lattice, and is one of the best materials for electrochemical sensors. Nano-GO is another graphene-based material that can be easily functionalized and has relevant optical properties

suitable for the biomedical applications, and a higher degree of oxidation that allows easy functionalization43.

Fig. 4: Graphene-based materials.The structures of pristine graphene (with sp2-hybridized carbon atoms), GO (chemically modified graphene), and rGO (reduced graphene oxide).

Full size imageIn addition to graphene and GO, some other emerging 2D materials from across the periodic table based on transition metals, chalcogenides, carbon group of elements, and others that possess

suitable properties are MXenes (Ti3C2, Ta4C3), Xenes (B, Si, P, Ge, Sn), transition metal chalcogenides (MoS2, WS2), and nitrides (GaN, BN, Ca2N)44. Based on their distinctive

characteristics, these 2D materials are chemically inert, flexible, transparent, and have a broad range of electronic (conductors, semiconductors, insulators) and optical properties. 2D

materials with a large surface to volume ratio, ultrathin thickness, tunable band structure, and interactions with bioanalytes are considered for sensing applications. The surface

modification by functionalization and defect engineering can tailor make these materials for sensing and next-generation biotechnology and healthcare applications45. In addition, the planar

structure of 2D materials is compatible with the fabrication techniques used for biomedical devices and their mechanical flexibility is appropriate for use in wearable and implantable

biosensors. A comparison of GO with other 2D materials for cancer detection applications46 is given in Table 2.

Table 2 Comparison of GO and other 2D materials for cancer detectionapplications.Full size table

For practical applications of graphene-based materials, the synthesis method should be carefully selected to obtain desirable properties and some commonly used synthesis methods (Fig. 5) are

briefly discussed here. 2D graphene was first synthesized by “peel off” method by peeling a monolayer of graphene using pencil and a sticky tape and it produced pure graphene monolayer with

a honeycomb lattice, but it generates only small samples and thus other methods have to be used for bulk samples47.

Fig. 5: Synthesis of graphene oxide.Some commonly used methods for the synthesis of GO. a Mechanical exfoliation “Scotch Tape” method. b Liquid exfoliation. c Chemical vapor deposition (CVD). d Hummers method. a–c is

reproduced with permission from ref. 45, Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

Full size imageAnother method using liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite in surfactant solutions or water produced 40% of 2D graphene sheets with thickness <5 layers and ~3% single layers of graphene48.

Chemical methods for the synthesis of graphene are more promising as they provide ease of chemical modification and production in large quantities. The introduction of some defects in

graphene is a major disadvantage associated with chemical methods, while reduction or oxidation steps could lead to morphological damage of graphene. The graphite oxide prepared by Hummer’s

method that was later modified and improved to avoid the emission of toxic gases can be exfoliated to result in a single layer of graphite oxide, known as GO. The chemical growth methods for

the synthesis of graphene and rGO are molecular beam epitaxy and chemical vapor deposition. To obtain hydrophilic GO sheets, graphite is first oxidized into graphite oxide and then followed

by thermal or mechanical exfoliation. The oxygenated graphene sheets and graphite oxide are both layered materials consisting of GO sheets having oxygen-containing groups on the edges and

basal planes. Finally, the chemical reduction step is performed to retrieve graphene from GO and the retrieved product is also strongly hydrophilic. These bulk scale production methods

produce 99% multilayer graphene and only 1% monolayer graphene sheets, and it may be due to the inherent ability of monolayer graphene layers to stack themselves into multilayer

nanostructures, because of the strong van der Waals interactions49,50.

Functionalization of GO with aptamersThe modification of graphene generally involves oxygenation, hydrogenation, and fluorination by employing proper functionalization routes. The surface functionalization of GO can be

primarily carried out using either covalent or non-covalent approach. In the covalent approach, oxygen-containing groups (-O, -OH, and -OOH) present at the surface of GO form covalent bonds

with other polymers, molecules, biological entities, and nanoparticles to be attached, whereas the non-covalent functionalization of GO generally involves hydrogen bonding or electrostatic

interactions, which occur because of the high electronegativity of surface and it also imparts hydrophilic nature to GO. The non-covalent functionalization of GO with proteins or DNA is also

useful for bio-recognition. As graphene consists of sp2-bonded C atoms, it is chemically unsaturated and can bind to other species covalently and transforms to sp3 hybridization. Along with

graphene, GO and rGO also possess different oxygenated species (hydroxyl, carboxyl, epoxy groups, etc.) that enters during the oxidation of graphite. The presence of these functional groups

in GO and rGO is helpful for their covalent functionalization. The process of covalent functionalization generally depends on the oxidation of graphene. The carboxyl and carbonyl functional

groups are often present in graphene, prepared by the reduction of GO or using oxidation methods51. The inert graphitic structures can be modified by the oxidation of graphene, resulting in

an increase in the density of carboxyl and carbonyl functional groups but this method heavily alters the properties of graphene48,52. These groups are then functionalized with various

biomolecules via their amine functional groups. However, in the absence of free radical addition reaction, which is a pre-oxidation step, the electronic properties are not much affected by

the covalent modification of the graphitic surface.

The non-covalent approach modifies graphene with suitable functional groups but does not affect its original properties. The physical adsorption of the pyrimidic and puric bases of aptamers

on the C–C hexagonal network of graphene via the favorable π–π stacking interactions is the most promising and simpler way to construct graphene-based aptasensors. The chemical and

electronic properties of graphene have been observed to change upon non-covalent functionalization. Due to the relatively weak van der Waals or π–π interactions between graphene and the

aromatic molecules, the non-covalent functionalization of graphene does not perturb its π-conjugated structure, and as a result, helps in retaining its excellent physical properties. The use

of a modified graphene electrode to bind aptamers by physical adsorption has also been reported17,53. In another approach, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, which adsorb strongly on graphene via

π–π stacking interaction, have been used for the non-covalent functionalization of graphene54. For example, the utilization of pyrene butyric acid results in a robust and stable

functionalization with π–π stacking of the four aromatic rings, whereas additional covalent functionalization of biomolecules via their amine functional groups can be carried out at the

terminal acid groups. This protocol offers the advantages of covalent modification without altering the basic graphitic properties. In addition, the electrostatic adsorption is generally

used for the assembly of aptamers onto transducers. Both these approaches are thus useful for the development of GO–aptamer conjugate materials for aptasensors. In addition, phosphoramidate

and amide reactions are also used for the preparation of aptamer biosensing system based on these materials.

The sensing capability of graphene-based materials (G, GO, and rGO) can also be easily controlled by functionalization. The chemical doping of graphene with various functional groups and

atoms generally results in a change in its optical, electrochemical, and electrical properties.

GO holds great potential in biology, having wide applications in DNA/protein assays as well as drug delivery owing to its high-yield production, low-cost, and distinctive physicochemical

properties55. GO can be used for the detection of molecules with high reduction or oxidation potentials, such as nucleic acids, due to its large surface area and wide electrochemical

potential window. GO interacts strongly with single-stranded nucleic acids. The defects and edges present in GO give rise to a high electron transfer rate, which makes it suitable for use in

biosensing applications. The functionalization of GO with aptamers (Fig. 6) can be achieved either with covalent bonding for the development of reusable biosensors or via non-covalent

attachment of aptamers on GO56. GO–aptamer conjugates emerge as promising materials for use in aptasensors and drug transporters. The oxygen-containing functional groups in water-soluble GO

allow interactions with various molecules via non-covalent, covalent, and/or ionic interactions. The stable adsorption of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) onto the GO surface due to π-stacking

interactions is crucial for the design of biosensing aptasensors. This binding interaction of GO with ssDNA provides the basis for its use in molecular recognition and detection of

biomolecules. GO is a super-quencher to a large number of fluorophores by Förster (or fluorescence) resonance energy transfer (FRET) or via nonradiative dipole–dipole coupling. The enzymatic

digestion and degradation of biomolecules in biological environments can be protected by GO using its steric-hindrance effects.

Fig. 6: GO–aptamer conjugation.Illustration of the conjugation of GO with aptamer to obtain GO–aptamer conjugate-sensing materials.

Full size imageUse of conjugation strategy allows various aptamers to act as exchangeable building blocks for functionalizing carbon nanomaterials to facilitate their applications in clinical translation.

The conjugates of aptamers with GO can help in developing high-performance aptasensors. GO exhibits non-covalent interactions with aptamers through π–π stacking interactions between purine

and pyrimidine bases. Such aptasensors based on multi-specific aptamers are being exploited to eliminate cancer-specific tumor cells.

2D GO–aptamer conjugate materials for cancerdiagnosis

With a tremendous increase in reports on biomarkers in cancer research, there is a growing demand to develop rapid and robust cancer diagnosis methods. In this regard, the large surface

area, high conductivity for surface functionalization, and efficient fluorescence quenching by GO are very important for applications in biological sensors and in the detection of

biomolecules. Hybridizing aptamers as cancer diagnosis probes with GO’s distinct fluorescence quenching properties has been exploited for detecting different cancer biomarkers. The detection

of main types of cancer biomarkers (PSA, mucin 1 (MUC1), CCRF-CEM, and circulating tumor cells (CTCs)) using GO–aptamer conjugate materials is discussed in the following

sections.

Prostate-specific antigenPSA is a 33-kDa single-chain glycoprotein that is used as a standard marker for prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and monitoring57. An accurate detection of prostate cancer can

significantly reduce the mortality risk. Screening serum for the presence of PSA is one of the most common approaches for prostate cancer detection. The studies on aptamer-based detection of

prostate cancer are constantly gaining momentum since the past few years. Aptamer A10 is one of the most suitable aptamers related to prostate cancer that has been employed as a

prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) inhibitor imaging agent as well as a drug delivery carrier. It can target solid tumors efficiently, resulting in a reduction in the size of tumor

and proliferation of prostate cancer58,59,60. Graphene is often used to enhance the conductivity and sensitivity of immunosensors for an ultralow (down to 2 pg mL−1) detection of PSA61 in

blood serum.

GO exhibits high affinity to different aptamers, and biosensors based on GO can be extended to a wide range of targets. For example, GO-based aptasensors using different aptamers, but the

same sensor, were reported for the detection of PSA, thrombin (TB), and hemagglutinin. Both types of aptamers (DNA and RNA) immobilized on the surface of GO were found to be sufficiently

active. A GO aptasensor having 2 × 3 linear-array detected multiple (TB and PSA) targets on a single chip62. On-chip GO aptasensor is reported to maintain its biological activity even after

a change of DNA aptamer from TBA to PSAA. The decrease in fluorescence intensity observed at a lower concentration confirmed the selectivity for PSA detection. In a similar strategy,

dual-modality biosensor designed by coating GO–ssDNA on a gold electrode and incorporated with poly-l-lactide nanoparticles for signal amplification was used to simultaneously detect

vascular endothelial growth factor and PSA in human serum63. A different noteworthy targeting strategy exploited amplified fluorescence method using deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) based on

quantum dot (QD)–aptamer/GO sensor that can sense PSA with high sensitivity64. In the presence of PSA, aptamer binds to the target PSA and releases the aptamer probe away from GO nanosheet,

restoring the fluorescence of QD. On the exit of DNase I, nuclease is unable to cleave aptamer, which is protected by GO but cleaves the released aptamer, thus liberating PSA and QD. The

released PSA binds to another aptamer and a new cycle is started (Fig. 7a). The sensitivity for detecting PSA showed a significant improvement up to fg mL−1 upon amplification by DNase I.

High selectivity and steady fluorescence signals were reported by using anti-photobleaching QD and aptamer as fluorescence indicator and recognition element, respectively. This strategy

could successfully detect PSA quantitatively in human serum (Fig. 7b, c)64.

Fig. 7: Detection of PSA.a DNase I and QD–aptamer/GO-based hybrids for amplified detection of PSA. b PSA increased the fluorescence of QD–aptamer/GO significantly in the presence of DNase I (curve c → d) in

comparison with fluorescence recovery in the absence of DNase I (curve a → b). c The fluorescence intensity also increased with increasing PSA concentration suggesting high efficiency of the

detection system. Adapted with permission from ref. 64, Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

Full size imageElectrochemical PSA aptasensors have high reproducibility as the bio-recognition element and improve the analytical performance for direct detection of PSA by using modified nanomaterials on

the electrode surface. The electrode modified by rGO-MWCNT/AuNP (rGO-multiwall carbon nanotubes and gold nanoparticle) nanocomposite effectively captures PSA in the 0.005–100 ng mL−1

detection range61. A bio-receptor based on DNA aptamer complexes with PSA immobilized on the gold electrode surface exhibited good recognition property for the selective sensing of PSA65.

The bio-receptor showed an excellent response in the 100 pg mL−1 to 100 ng mL−1 range to the PSA with a very low (1 pg mL−1) limit of detection (LOD), and a three-fold enhancement in

sensitivity, as compared to conventional biosensors. The sensor displayed good selectivity even in the presence of serum protein HSA and homologous protein hK2. GO conjugate materials

designed by integrating GO with aptamers show significant enhancement in the selectivity, specificity, and detection limit of PSA (Table 3).

Table 3 GO–aptamer conjugate materials for PSAdetection.Full size table

Aptamers, in addition to being used in cancer detection and therapy, can also be used as potential drug carriers, being selective drug delivery vehicles due to the intercalating properties

of nucleic acids. The attachment of drug molecules to aptamers for targeted drug therapy can be achieved by covalent or non-covalent conjugation of chemotherapeutic agents to tumor-targeting

aptamers. Doxorubicin (DOX), an anticancer drug, which intercalates into the A10 aptamer, has been used to recognize PSMA and also acts as a remarkable drug carrier66. The dual-aptamer

complex is reported to be specific for both (+ve) and (−ve) PSMA prostate cancer cells, and as a result, DOX is delivered to the target cells in an effective and selective manner. Similarly,

to target the PSMA-positive cancer cells selectively, a pH-sensitive covalent linkage was used to conjugate DOX with a dimeric anti-PSMA DNA aptamer complex67.

Although nanomaterials exhibit applications as diagnostic and therapeutic agents, yet they lack selective targeting ability and hence aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials play a critical

role in the diagnosis and treatment of several diseases, including cancer.

CCRF-CEM cellsAcute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is one of the most prevalent malignancies among children and it arises due to the overproduction and aggregation of lymphoblasts, which are cancerous

immature white blood cells. These lymphoblasts rapidly multiply in the bone marrow resulting in damage and death by preventing the reproduction of normal blood cells as well as by

infiltrating into other organs. The pathogenesis time of ALL is relatively short, and the average survival period of patients without any treatment is 3 months. Therefore, an early diagnosis

of ALL is important for increasing the chances of survival. The low cure rate is probably due to drug resistance, poor tolerance, and less effective treatment. There is little progress for

relapsed and refractory ALL, whereas treatment based on high doses of chemotherapeutics results in serious, acute, and late complications in many patients that further highlights the crucial

need for more effective treatment of ALL. The current methods based on peripheral blood cells and bone marrows are costlier and less sensitive. Some GO–aptamer conjugate materials used for

the detection of CCRF-CEM cells are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 GO–aptamer conjugate materials for CCRF-CEM cells detection.Full size tableFunctionalized aptamers can be easily synthesized, modified, and used as cancer detection probes by integrating fluorescence quenching properties of GO and help in overcoming the current

obstacles for developing efficient aptasensors68. The GO functionalized aptamer against CCRF-CEM cells, isolated from the peripheral blood of a patient suffering from ALL, can selectively

capture the target cells from cell mixtures that also contain nontarget cells69. The binding of aptamers to GO by π–π stacking can significantly improve the stability of GO-based aptasensors

for leukemia cell detection70. The signal “turn-on” strategy effectively detects leukemia using GO and carboxyfluorescein-labeled Sgc8 aptamer (FAM–Apt)68 by utilizing aptamer as a target

agent and GO as a fluorescence quencher. GO interacts with FAM–Apt in the absence of leukemia cells and quenches fluorescence, but in the presence of target cells aptamers actively target

cells and fall off from GO leading to the recovery of fluorescence. A change in the intensity of fluorescence affected the concentration of cancer cells. On increasing GO, the fluorescence

intensity is reduced, implying that GO quenches fluorescence only when GO and aptamer are close to each other and hence are adsorbed together and the fluorescence is restored on adding

CCRF-CEM cells. However, the fluorescence intensity of FAM–Apt does not show any change in the absence of GO, indicating that the recovery of fluorescence is primarily due to the detachment

of aptamer from the surface of GO (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8: Detection of CCRF-CEM cells.a Schematic figure of the GO and FAM–Apt-based fluorescent material for detection of CCRF-CEM cells. b The fluorescence intensity increases with an increase in the number of CCRF-CEM cells

from 0 to 1 × 107 indicating efficiency, and c the CCRF-CEM gets higher fluorescence intensity than the other control groups, implying high specificity of the hybrid material for CCRF-CEM

cell detection. Adapted with permission from ref. 68, Copyright 2018, Springer.

Full size imageA higher fluorescence intensity of CCRF-CEM, in comparison to other control groups, clearly indicates the high specificity of the fluorescent aptasensor (Fig. 8b, c). Similarly, a GO-based

label-free and efficient aptasensor was reported for cancer detection at low concentration of cancer cells. The “turn-on” aptasensor having high sensitivity and low background signal is

crucial for the detection of rare cancer cells71. A FRET biosensor containing GO and a dye-labeled aptamer probe can also be used for the visual detection of cancer cells, despite having

relatively lower sensitivity72. However, the lower sensitivity can be further improved by designing a GO-based FRET aptasensor using a mix-and-detect strategy in which aptamers are mixed

with target molecules resulting in strong fluorescence during the detection process. A sandwich-type electrochemical aptasensor can also be a resourceful and sensitive detection system for

diagnosing CCRF-CEM cancer cells in which palladium nanoparticles functionalized carbon nanotubes were used as a nanoplatform to immobilize thiolated aptamer, along with a catalytically

labeled aptamer to amplify electrocatalysis73. The aptasensor is highly selective to CCRF-CEM cancer cells and the sandwich-type electrochemical aptasensor can detect up to 5 × 105 cells

mL−1 (CCRF-CEM) cancer cells in a human serum sample with 8 cells mL−1 detection limit.

Aptamers of CCRF-CEM cells designed as a hairpin aptamer probe (HAP) specifically bind to the target cancer cells, inducing conformational changes that can be easily detected71. In the

absence of target cells, HAP possesses a stable hairpin structure and exists in solution along with linker DNA, which binds with GO and quenches fluorescence signal for the FRET process.

Upon incubation of HAP with target cancer cells, conformational changes are induced due to the binding of HAP to protein receptors, leading to no FRET and a clear fluorescence signal. A rise

in the number of cancer cells results in the cleaving of more linker DNAs that amplified fluorescent signal. Using this GO-based fluorescent aptasensor system, quantitative information

about rare target cancer cells can be obtained. Fluorescence spectra for GO-DNA can be used to check the feasibility of this method for detecting CCRF-CEM cells and the quantitative analysis

of cancer cells could be made from the intensity of 520 nm signal. The detection limit of aptasensor was 25 cells, which is ~24 times lower than for the common fluorescence aptasensors. The

selectivity of this aptasensor towards CCRF-CEM was also confirmed by using some other cell lines (Hep3B and DLD-1 cells) and was found to be highly sensitive and selective to CCRF-CEM

cells along with reproducible results.

To successfully develop the screening assay for tumor cells, a multiplex microfluidic chip was combined with the GO-based FRET strategy72. The microfluidic channel pattern as well as the

corresponding master was prepared using mechanical micro-fabrication. The principle of a “signal-on” aptasensor used for the detection of CCRF-CEM cells is based on cell-induced fluorescence

recovery of GO/FAM-Sgc8. The fluorescence intensity recovers with the addition of GO/FAM-Sgc8 into the CCRF-CEM cells. However, the fluorescence intensity does not change in the absence of

GO, indicating that the fluorescence of free FAM-Sgc8 is not affected by CCRF-CEM cells. The free FAM-Sgc8 aptamer binds to GO via π–π stacking interactions and the fluorescence quenching

takes place through FRET. However, in the presence of CCRF-CEM target cells in GO/FAM-Sgc8 solution, FAM-Sgc8 is released from GO and quenched fluorescence is restored. In a similar

approach, an aptamer Cy5-labeled sgc8c on SWCNTs was assembled to develop an activable fluorescence-sensing platform74. The aptamer sgc8c was used as the recognition agent that binds to

CCRF-CEM target cancer cells with high specificity. In the presence of a target, it is the aptamer sgc8c, which is bound to the target cells and not SWCNTs and it was experimentally

confirmed by observing an increase in the intensity of Cy5 dye fluorescence. This shows that CCRF-CEM cancer cells can be clearly imaged due to the binding of the aptamer both in vitro and

in vivo75.

CCRF-CEM cancer cells, having a weak background signal and high sensitivity, have been detected by integrating microfluidic chip with microelectrodes based on the electrochemical oxidation

of hydrazine catalyzed by nanoparticles, changing the combination of microelectrodes and channel69. By using the cell aptamer as the sensing element, this system successfully captures target

cells doped in the blood samples. This strategy based on the microfluidic chip and using electrochemical signal can be exploited to develop portable and miniature point-of-care testing

devices.

In general, GO-based aptasensors developed for CCRF-CEM can also be used for the analysis of other cancer cells, because of their specific design along with the simple operation, high

selectivity, and good sensitivity for the diagnosis (preclinical and clinical) of cancer and its treatment. The highly sensitive fluorescent biosensing that is noninvasive and can carry fast

analysis with the spatial resolution has been effectively used in aptasensors, and is a powerful technique for detecting the morphological details relevant to biology and for monitoring

different physiological processes in living systems. Thus, it provides a promising strategy for an early diagnosis of cancer along with in vivo monitoring of drug release quantitatively and

in identifying various biological targets. The conjugation of aptamers with 2D nanomaterials thus enhances the sensing signal by more than three orders of magnitude.

Mucin 1Breast cancer is another major cause of death among women globally that is treated by conventional chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and radiotherapy. The lack of selectivity for breast cancer

tumor cells is, thus, one of the main drawbacks of these therapeutic treatments that results in undesirable adverse side effects. A continuous improvement in the methods used for breast

cancer treatment along with a clear understanding of the mechanisms responsible for it, and the availability of improved medicines can lead to better breast cancer treatment that is more

efficient and highly effective. Mucins are glycoproteins that play a critical role in mucosal protection and communication with the external environment. MUC1 (CA-15-3) is overexpressed in

breast cancer and hence can be one of the best tumor markers for breast cancer diagnosis and therapy75. Label-free aptasensor-based MUC1 detection approach uses functionalized GO at the

surface of graphite-based screen-printed electrodes with detection limit 0.6 ng μL−1 and a sensitivity of 0.62 μA μL ng−1 cm−2 75.

The use of nanotechnology for cancer therapy has been extensively studied recently and involves the functionalization of nanomaterials with specific biomolecules to make therapy more

efficient and safe76,77,78. Aptamers can bind a target using lock and key model and a number of aptamers having a high affinity towards MUC1 have been isolated79 for the design of more

efficient aptamer-based therapeutic methods that are urgently required for cancer treatment. Various cancers such as colorectal, prostate, lung, stomach, and breast cancer are related to

MUC1. In the aptamer-based MUC1 detection, one approach can be the use of fluorescence intensity of oligonucleotide-tagged QDs via MUC1 peptide80. GO was also used for the fluorescence

quenching of single-stranded dye-tagged MUC1-specific aptamer81 for sensitive detection in both buffer and blood serum. ERET (electro-chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer) can also be

applied for the sensitive detection of MUC179. Table 5 highlights the GO–aptamer conjugate materials used in the detection of MUC1.

Table 5 GO–aptamer conjugate materials for thedetection of MUCIN 1 (MUC1).Full size table

GO, due to its high loading capacity, is an excellent drug carrier that can be employed as a nanomatrix using GO and AuNPs in a single system, leading to an enhancement of the photothermal

effects on tumors. A nanomatrix with the capability to target-specific human breast cancer cells followed this design using Apt–AuNP–GO hybrid nanomaterials as highlighted in (Fig. 9a)82. An

aptamer-guided AuNP–GO was used in the near infrared region of MUC1-positive breast cancer cells (MCF-7) and conjugation of MUC1 aptamers to AuNPs by a strong Au–S bond followed by its

adsorption on GO that increased the binding efficiency of MUC1 aptamers82. The high light-to-heat conversion efficiency of Apt–AuNPs–GO in the near infrared region exerts therapeutic effects

on MCF-7 cells even at an ultralow concentration and without affecting healthy cells (Fig. 9b). The Apt–AuNP–GO nanocomposites integrate the properties of aptamers, GO, and AuNPs and

possess specific targeting, good biocompatibility, and ability to destroy tumor cells, indicating great potential for their use in the photothermal therapy of breast cancer83. In another

similar strategy, MUC1 aptamer (5TR1) with high affinity and selectivity towards MUC1-positive cancer cells was also generated successfully83.

Fig. 9: Aptamer–AuNP–GO nanocomposites formucin detection.

a Apt–AuNPs/GO hybrid nanoparticles matrix complex: a First AuNPs are functionalized with aptamer (Apt–AuNPs) and then mixed with GO to obtain Apt–AuNP–GO hybrid nanoparticles. b Apt–AuNP–GO

hybrid material is then surface immobilized with MUC1-positive breast tumor cells. Irradiation with NIR Laser light for photothermal therapy results in targeted inhibition of breast cancer

MCF-7 cell growth. Coupling the AptMUC1–AuNPs/GO hybrid material with laser desorption for tumor tissue imaging helps the detection of tumor cells by observing Au cluster ions. Adapted with

permission from ref. 82 Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society, and ref. 86 Copyright 2015, Springer Nature.

Full size imageFRET occurring between an excited state (donor) and a proximal ground state (acceptor) has been extensively employed in biological analysis. GO has a unique microstructure with

oxygen-containing functional groups and fluorescence quenching ability84. A GO-FRET aptasensor using a dye-labeled aptamer on GO surface can be effectively used for the detection of MCF-7

breast cancer cell85. An ultrasensitive aptasensor based on FRET between carbon dots (CDs) and GO used the strong fluorescence and biocompatibility of CDs84. In the aptasensor, the MUC1

aptamer was covalently conjugated to CDs (aptamer–CDs) to detect MUC1 protein using high-affinity interaction between the aptamer and MUC1 protein. A 25-base aptamer with specific binding

for MUC1 peptide and the fluorescence of the aptamer–CDs can be efficiently quenched by GO due to FRET. This aptasensor specifically detected MUC1 protein in the 20.0–804.0 nM linear range

with high sensitivity and with a detection limit of 17.1 nM. As all the materials used in the sensing system have excellent biocompatibility, they can be used in vivo and in vitro84. The

MUC1 binding aptamer conjugated with nanoparticles of gold and GO (AptMUC1–AuNPs/GO) was coupled to laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry for the detection and tissue imaging of

tumor cells86. The primary function of AptMUC1 is to identify and bind to native MUC1 at the surface of breast cancer cells (MCF-7) (Fig. 9b). Laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry

analysis demonstrates the selective binding of nAptMUC1–AuNPs/GO nanocomposite to MCF-7 cells. Large density and a higher flexibility of AptMUC1 on the GO surface enhanced the cooperative

and multivalent binding affinity of the platform for MUC1 on the cell membranes. The labeled MUC1-overexpressed MCF-7 cells with AptMUC1–AuNPs/GO resulted in the detection of 100 MCF-7

cells.

Although chemotherapy is widely used in cancer treatment, yet this toxic and invasive procedure is not desirable due to its adverse side effects. The research for methods to overcome some of

the negative side effects is currently being pursued. The abnormal overexpression of MUC1 in cancer cells can be exploited for targeted drug or gene delivery into cancerous tissues.

As no MUC1 antibody is yet commercially available, the use of MUC1 aptamers as anticancer agents has emerged as a promising strategy. Thus, aptamers have great potential as an attractive

class of pharmaceuticals, being moderate in complexity and size compared to antibodies, proteins, and normal organic drugs having similar affinity and specificity.

Circulating tumor cellsCTCs circulate in the bloodstream, and as a result, travel to different tissues of the body after they are shed naturally from the metastatic tumors. It can result in metastasis and is a

crucial route for spreading cancer, thereby leading to numerous cancer-related deaths87. The first study of the detection of CTCs in cancer patients was reported in 1869, ~150 years ago, but

only recently has it been widely studied for cancer research. CTCs belong to a category of extremely rare cells in the blood vessels and the detection of CTCs is very challenging due to

their very low abundance. The concentration of CTCs in blood can be helpful for an early evaluation of the recurrence of cancer and effectiveness of chemotherapy. The phenotype

identification and molecular metastasis can play a critical role in the development of personalized treatment for cancer patients. The recovery rate, purity, and the LOD are most important

indicators for the CTC detection.

Nanotechnology holds great promise for the CTCs isolation and detection, and the related properties of nanomaterials can help to overcome the problems of low CTC capture efficiency and

purity. Materials with a large surface to volume ratio are suitable for efficient cellular binding in the complex blood matrix and CTCs also favor nanostructured surfaces as they have

similar scales on cell surface88. The capture efficiency and specificity of CTCs can be significantly enhanced using nanomaterials functionalized with aptamers. As antibodies have limited

availability and specificity, so aptamers emerge as a better alternative for use in CTC detection methods. In addition, the small molecular weight of aptamers (8–15 kDa) results in faster

tumor penetration and blood clearance.

Differential cell-SELEX, which is less expensive and much faster, can be employed for in vitro production of aptamers to target CTCs. The enrichment of multivalent CTCs and their analysis

using aptamers, specific to the molecular signature, can be helpful in elucidating the intrinsic heterogeneity of CTCs. A specially designed aptamer can also be used for quick and efficient

isolation of CTCs. GO–aptamer-based porous membranes synthesized for capturing targeted tumor cells can efficiently capture and accurately identify multiple types of CTCs89. The GO membranes

developed with pore size in nanometer are capable of blocking ions or molecules having a size >9 Å in the hydrated state, but are unable to filter and capture CTCs due to smaller pore

size56. If porosity of the membranes is in the 20–40 µm size range, then it allows normal RBCs to pass through the membrane and captures tumor cells selectively, as different aptamers are

present in the 3D space. Multiple types of CTCs can be detected in blood by attaching various surface markers to nanoplatforms, which can capture and identify different types of CTCs and for

this, different aptamers could be covalently attached to the porous GO membrane. The S6, A9, and YJ-1 aptamers, which bind specifically to HER2, PSMA, and CEA, respectively, can be used for

detecting different types of CTCs. The microporous nature, high surface area, large mechanical strength, and biocompatibility of GO enables its use as a macro-scaffold. The

aptamer-functionalized porous GO membranes can capture separately and simultaneously, the SKBR3 breast cancer cells, LNCaP prostate cancer cells, and SW948 colon cancer cells, present in the

infected blood. GO acts as a highly efficient quencher and hence fully quenches fluorescence from the dye upon attachment of dye-conjugated aptamers to GO. Cancer cells, however, bind to

aptamer conjugated with dye only in the presence of targeted cancer cells, thus enhancing the distance between GO and dye, and therefore fluorescence persists. The GO porous membrane is thus

highly selective for capturing different types of targeted cancer cells with 98% efficiency identified via multicolor fluorescence imaging.

Based on the selective biosensing property and therapeutic capability of functionalized GO, an aptamer-conjugated theranostic GO-based assay has been reported for cancer diagnosis by using

the detection of CTCs from blood90. The photoluminescence properties of graphene were observed by functionalizing GO with oxygen-containing functional groups or by decreasing its size to the

nanometer range. The tunable fluorescence properties of GO were exploited to develop hybrid graphene as a multicolor luminescent platform that was used for the selective imaging of G361

cancer cells. Advanced glycation end product (AGE)-aptamer, being selective to G361 cells, was attached to hybrid GO and used for the selective imaging of G361 (malignant melanoma). A

water-soluble photosensitizer indocyanine green (ICG)-bound magnetic nanoparticle attached GO platform uses simultaneous photodynamic and photothermal synergistic targeted cancer therapy.

Hybrid GO coated with thiolated glycol avoids the nonspecific interactions with cells and cell media. After PEGylation, NH-modified AGE-aptamer was attached to acid chloride functionalized

GO and the morphology of hybrid GO showed no change during aptamer binding process. Keeping the chemical composition and size same, fluorescence properties of magnetic GO could be controlled

by changing the excitation energy. In hybrid GO, the formation of reactive oxygen species in the presence of light has been used by ICG to kill G361 cancer cells. The efficiency of

photodynamic killing by hybrid GO depends upon the reactive oxygen species forming capability of ICG, which increases in the presence of AGE-aptamer containing hybrid GO. The photothermal

effect of GO increases the chances of forming singlet oxygen that enhances the photodynamic cancer cell killing efficiency.

The transfer of the findings of CTC research from the laboratory to the clinical practice is relatively slow and the unclear benefit of using CTCs in decision making for the treatment is

widely accepted. Thus, an increasing knowledge of CTCs and related materials can provide further insights and future studies should be related to using proteomics and genomics to evaluate

CTCs. Besides efficient CTC detection, there is a growing need to develop highly efficient CTCs isolation and purification methods for molecular and functional analyses.

Other cancerbiomarkers

In addition to the most prevalent cancer biomarkers (PSA, MUC1, CCRF-CEM, and CTCs) discussed above, few other cancer cell lines are also reported and some of them are discussed here

briefly. A dual-aptamer-functionalized GO complex uses two types of aptamers (Sgc8c and ATP) and GO for the detection of Molt-4 cells (T- cell line, ALL)91. The aptamer Sgc8c binds to

protein tyrosine kinase-7, which is a major biomarker for T cells ALL, with high sensitivity and selectivity. The dual-aptamer-functionalized GO complex shows a significant fluorescence

emission for target cells while it does not internalize into normal cells (U266 cells). In a similar study, a label-free optical sensing platform captures TB, being a biomarker of pulmonary

metastases, developed by using RuOMO-, GO-, and a TB-specific pair of aptamers92. The restoration of the fluorescence of RuOMO, which was pre-quenched by GO detects TB. In another approach,

the hybrid structure of GO–ssDNA effectively quenched by GO detects liver cancer biomarker (alpha-fetoprotein) sensitively with a detection limit of 0.909 pg mL−1 over 1–150 pg mL−1 range93.

HER2 is a marker for breast cancer and an immunosensor based on HER2-specific aptamer detected HER2 by depositing a film of rGO-C on the glass carbon electrode by immobilizing

amino-terminated aptamers94. Table 6 summarizes the GO–aptamer conjugate materials used for the detection of some other cancer biomarkers.

Table 6 GO–aptamer conjugate materials fordetecting other cancer biomarkers.Full size table

A FRET sensor constructed on the surface of GO by assembling fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled peptide (Pep-FITC) via covalent binding (GO-Pep-FITC) has been reported to be sensitive, fast,

and can accurately detect (detection limit: 2.5 ng mL−1) matrix metalloproteinase-2 in complex serum samples. The construct allowed for rapid (within 3 h) detection of matrix

metalloproteinase-2, with good accuracy and having a relative standard deviation of ≤7.03%, even in complex biological samples95. Similarly, a fast and highly sensitive immunoassay detects

CA-125 via chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer to graphene CDs, exhibiting low (0.05 U mL−1) LOD along with a much wider (0.1–600 U mL−1) linear range for CA-125 in the buffer

solution. No additional external excitation source is required and it serves as a good substitute for FRET-based assay. Similar results have also been reported by using this immunoassay in

the presence of 50% blood plasma with a low LOD of 0.08 U mL−1. The sensing platform could also be integrated with an array chip-based device for high-throughput multiplex detection96.

2DGO-based sensing platform for cancer diagnosis

The fluorescence quenching capability of graphene induced by FRET is utilized in graphene-based fluorescence biosensors. Graphene-based materials (G, GO, and rGO) are being used extensively

as key materials in biosensors for the detection of biomarkers in cancer research97. In addition, control of the properties of graphene by reduction or functionalization is also very useful.

The presence of a large number of carboxyl groups and the strong adsorption of certain biomolecules by graphene helps in the functionalization of GO. GO interacts with ssDNA concurrently

and can quench fluorescence efficiently as they are strong acceptors of FRET because of their broad absorption in the visible region. The effectiveness of GO in quenching fluorescence is

significantly higher than other carbon nanomaterials. The efficient quenching of dye fluorescence takes place when the dye lies very close to the surface of GO, as the energy transfer

efficiency depends inversely on the sixth power of the donor–acceptor distance. Thus, FRET is highly sensitive to even a small change in distance. In addition, GO is capable of enhanced

electron transfer and also has high conductivity, unique pliability, and biocompatibility. These properties are helpful for the application of GO in biosensing techniques for cancer

detection and various fluorescent biosensors have been reported for the detection of cancerous cells and cancer markers62,71,72,98,99.

Direct cancer cell detection by the microfluidic chip based on aptamers is severely limited as most of the aptamer-cell interactions do not result in an output that could be easily measured.

Conjugating nanomaterials with bio-molecular recognition events can provide a better strategy for the development of molecular diagnostic tools. The distinct optical and electrical

properties of GO enables it’s potential in sensors and fluorescence quenching methods. Moreover, GO can also differentiate between various DNA structures (ssDNA, dsDNA, and stem loop) based

on distinct interactions among them62. Highly sensitive FRET aptasensors based on the super-quenching property of GO, along with its special ability for DNA absorption have been proposed. An

efficient “signal-on” FRET-based aptasensing strategy has been employed recently for visualizing cancer cells72. The analytical efficiency to detect target cancer cells is greatly enhanced

and many samples in microliter quantity can be simultaneously analyzed with a microscopy system.

The fluorescence of GO/FAM-Sgc8 has been observed to recover with the addition of CCRF-CEM cells and is primarily due to the existence of strong interactions between aptamers and cells. The

addition of GO/FAM-Sgc8 into the CCRF-CEM cells enables the recovery of more than half of the initial fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence intensity, however, does not show any change in

the absence of GO, which indicates that the fluorescence of free FAM-Sgc8 is not much affected by CCRF-CEM cells. The above results indicate that free FAM-Sgc8 as an ssDNA aptamer binds

easily to GO through π–π stacking interactions between GO and DNA bases, and it results in fluorescence quenching via FRET. On the other hand, in the presence of target CCRF-CEM cells in the

GO/FAM-Sgc8 solution, a strong binding between aptamers and target cells changes the free-folding structure of ssDNA to a stable hairpin structure, resulting in the release of FAM-Sgc8

probe from the surface of GO and the quenched fluorescence of GO/FAM-Sgc8 is recovered. Confocal fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry could be used to confirm the specific interactions

between aptamers and target cells.

An aptamer–FAM/GO–nS nanocomplex developed as a real-time biosensing platform has been effectively used in the living cell systems. ATP aptamer is well studied due to its significance in

living systems, whereas GO is a good carrier to transport genes into the cells. The incubation of ATP aptamer labeled with FAM into the GO–nS led to the formation of Apt–FAM/GO–nS and

resulted in nearly 100% fluorescence quenching after 5 min of incubation. The quenching occurred with very fast kinetics on Apt–FAM/GO–nS due to the FRET between FAM and GO–nS98. The aptamer

could easily target ATP and also form a duplex configuration that is released from the GO–nS surface due to weak adsorption. Up to 85.7% fluorescence recovery is obtained with ATP and is

due to the specificity of the particular aptamer. High selectivity and sensitivity of Apt–GO-nS nanocomplex could be potentially used for intercellular ATP monitoring in living cells.

Non-covalent binding of oligonucleotides with GO-nS plus very high solubility and good biocompatibility of GO-nS has enabled it to be an effective cargo as well as a good protector for the

cellular delivery of genes, peptides, and proteins. The super-quenching property and the resulting FRET function indicate that GO-nS can be used as a sensing platform for different

fluorescent probes.

The integration of carbon nanomaterials with suitable bio-molecular recognition events leads to a modern approach for the development of improved molecular diagnostic devices99. The binding

of GO with ssDNA through hydrophobic and π-stacking interactions can result in fluorescence quenching with FRET. GO–aptamer interactions have been proposed as turn-on probes for the

detection of DNA and other small molecules. The aptamer of CCRF-CEM selected by SELEX and designed as HAP can bind specifically with the target cancer cells. A label-free aptasensor, which

is highly sensitive and specific, could quantitatively detect rare CCRF-CEM cancer cells, by coupling CTCESA with the GO-based FRET sensor71. The aptasensor improved the selectivity,

sensitivity, and also has a much lower detection limit of 25 cells.

Due to their facile fabrication, high sensitivity, and biocompatibility, biosensors on graphene-based materials, such as graphene field-effect transistors (GFETs), are also important.

GFET-based gas sensors can detect even a single gas molecule, and this extraordinary performance is attributed to the large carrier mobility of graphene, which results in low noise100.

GFET-based biosensors can also be used for detecting biomolecules such as proteins and DNA, and the bio-signals are produced by the interaction between graphene and bacteria or

cells.

Critical discussionThe applications of GO–aptamer conjugate materials in cancer research are constantly gaining momentum with studies aimed at optimizing and enhancing the efficiency of devices based on these

materials. The presence of GO in GO–aptamer conjugate materials facilitates an increase in the binding sites that can be used for additional functionalization with various biological

molecules. The surface functionalization of GO can also increase biocompatibility, in addition to decreasing cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo, as the surface modification drastically lowers

their toxic interactions with living systems. The short- and long-term toxicity of graphene-based materials generally depends on the number of oxygen groups present at the surface and those

with higher C/O ratio are less cytotoxic and it strongly affects the cellular behavior. The degradation of the formed structures is also important and our immune system can degrade pristine

graphene, implying that these materials can be fully removed from the body once their function is completed. Thus, the surface properties of 2D conjugate materials play a crucial role in

their interactions with various cells and biomolecules.

The effectiveness of GO in quenching fluorescence coupled with its distinct interactions with ssDNA has provided the basis for their use in molecular recognition and optimization of

biosensors and other biological devices for disease detection and cure. The presence of oxygen-containing hydrophilic groups in GO allows π–π stacking and electrostatic interactions with

nearby molecules, and as a result accommodates drugs that can bind physically/chemically at the surface for use as a drug delivery vehicle, that also includes anticancer drugs. As an

example, GO functionalized with amino groups and combined with carboxymethyl cellulose is effectively used as an anticancer system for the controlled and targeted release of DOX drug101.

The aptamers form stable complexes with GO, and adopt specific conformational structures enabling high specificity towards the targets. In comparison to antibodies, the use of aptamers in

GO–aptamer conjugates is advantageous as they are highly stable and a change in temperature, pH, and ionic conditions of the environment does not affect their performance58,102. A relatively

smaller size of aptamers is very helpful for deeper penetration in tumors103.

GO–aptamer conjugate materials can also sensitively capture CTCs from the blood of cancer patients. The isolation of CTCs is crucial to prevent tumor metastasis as they can transport cancer

to secondary sites, forming new metastatic tumors, a major cause of mortality. Functionalized GO-based chip can isolate CTCs from blood samples of cancer (pancreatic, breast, and lung)

patients but exhibited positive results only in the presence of GO, and hence can be used in biosensors for targeting biomolecules in the blood samples of patients104.

The specific binding ability of GO–aptamer materials to cancer-related markers and cancer cells is thus beneficial for early detection of cancer. The GO–aptamer conjugates are optimal

bio-receptors in aptasensors because of their high binding affinity to aptamers. The conformation of aptamer changes upon binding and this property is frequently exploited for target

detection in aptasensors105. Aptasensors can detect food-borne pathogens, chemicals, disease markers, and heavy metals, and for that many electrochemical, optical, and colorimetric methods

have been designed for cancer detection. The conjugate materials based on aptamers, thus, provide a noninvasive and an economical cancer testing, even from the presence of very low levels of

biomarker in the blood, urine, or other bodily fluids. The development of biosensors based on a wide range of nanomaterials and with sensitivities in the clinical range is, thus, most

crucial for commercial use106.

Fluorescence sensing using GO–aptamer conjugates is widely preferred in cancer diagnostics as fluorescence biosensors with simple and economical operation possess high sensitivity and

efficiency107. While there is no change in the fluorescence signal of the fluorescently labeled antibodies upon binding to the target, the ligand-induced transitions of the aptamer’s

secondary structures can be easily tracked using covalently or non-covalently attached luminescent probes. The fluorescent biosensors based on GO–aptamer conjugates generally utilize

fluorescently labeled or label-free aptamers, and the “signal-on” and “signal-off” sensor-based FRET strategies. The change in signal reflects the extent of the binding process, which

depicts either an increase (“signal-on” mode) or a decrease (“signal-off” mode), allowing the quantitative measurement of the target concentration.

The binding capabilities of aptamers used in GO–aptamer conjugates can also be controlled by incorporating them in pH-activable systems. The aptamers that get activated at weakly acidic pH

can control the drug delivery system and ensure the uptake of nanoparticles by the cells in the acidic tumor microenvironment, thereby preventing the off-target toxicity. The control of pH

at which an aptamer can bind or release its cargo can help to improve GO-based systems. An aptamer selected at neutral pH loses target affinity at low pH, whereas affinity between a DNA

aptamer and the GO surface increases at low pH108. An adenosine aptamer labeled with a fluorescent marker adsorbed onto GO surface could result in the quenching of the fluorescent label109.

An increase in fluorescence was observed when the aptamer bounds adenosine in its presence, but gets desorbed from the GO surface at neutral pH. The pH-activable aptamer systems can help in

explaining the pH-responsive binding mechanism and aid in developing systems for different applications. The efficient targeting ability of these materials provides a promising way to

deliver imaging agents and drugs for cancer imaging and therapy and reduces the side effects of most chemotherapeutic drugs.

Despite many advantages, GO–aptamer-based aptasensor materials are still at the developing stage as compared to other fully developed biosensing tools. Some technical hurdles that need to be

urgently addressed include desorption of nanomaterials and bio-elements from aptasensor device over the time, effect of the size variation of nanomaterials on biosensor performance,

specificity, and low affinity of aptamers towards small inorganic molecules. One of the most important challenges in the practical applications of these aptasensors is, however, their

ability to identify the analyte in the complex environments and real world. As the body fluids contain a mixture of ions, particles, and macromolecules, they could generate specific signals

in the detection process. Hence, the feasibility of the GO–aptamer-based sensors should be explored for the recognition limits in the complex environments. GO–aptamer conjugates are emerging

materials for cancer diagnosis and therapy and provide many advantages for imaging and drug delivery, but some critical issues, such as toxicity and pharmacokinetics, remain to be fully

addressed before clinical use.

Conclusions and future outlookIn this review, we have discussed emerging 2D materials based on aptamer-functionalized GO that can be very beneficial for developing highly sensitive biosensors for cancer diagnosis.

Conjugating aptamers as cancer detection probes with GO’s peculiar fluorescence quenching properties can aid in the development of GO–aptamer-based biosensors. GO biosensing is an effective

technique for label-free cancer cell detection at an early stage. Biosensors based on conjugates of GO and aptamers exhibit specific design along with easy operation, large sensitivity, and

high selectivity for preclinical and clinical applications in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. GO functionalized with aptamers can be used to specifically recognize various cancer

biomarkers such as PSA, MUC1, CCRF-CEM, and CTC cells with low detection limit and over a wide linear range. GO-based sensors have promising features and huge potential for use in the

detection and theragnosis of various cancers. These materials can facilitate the development of low-level ultrasensitive detection techniques and also help in overcoming some of the existing

drawbacks such as time, cost, and labor. Thus, hybridizing GO with bio-molecular recognition agents can prove to be an improved strategy for the expansion of molecular diagnostic tools.

GO-FRET aptamer-based biosensing and electrochemical biosensing techniques can significantly improve the analytical efficiency for the detection of target cancer cells in complex

multi-samples.

Cancer diagnosis at the early stages is difficult due to its high innate heterogeneity. The presence of various types of proteins, chemical species, and ions in actual biological samples can

also give rise to false-positive response, which makes the detection of cancer biomarkers a challenging task. In this regard, the ability of graphene and its different derivatives to

conjugate their distinctive chemical structure and characteristic optical, electronic, mechanical, and thermal properties into an excellent sensing platform is a major milestone in the

diagnosis of cancer at the initial stages. GO can also be functionalized with various biological materials, such as aptamers to develop conjugate materials whose properties not only depend

upon individual constituents but also on the interactions between them. As antibodies are costly, so studies are underway to substitute them with suitable aptamers that are cost-effective

and stable recognition elements. The development of GO–aptamer 2D materials having significant improvement in targeting cell is only possible due to the high binding affinity and specificity

of aptamers against various cancer cells. Since aptamers can be generated with a simple method and can also be modified with various carbon nanomaterials, including GO, it takes care of

drawbacks related to low sensitivity and higher costs, and aptamer–GO conjugate materials display good potential for use in cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Generating quality aptamers with higher stability, easy synthesis, and optimum target specificity, SELEX need modifications and these issues can be resolved by coupling SELEX with

next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics to drive aptamers for clinical use. The success rate of cell-SELEX-based aptamer selection, generally used in cancer research, could be further

enhanced by employing modified SELEX selection methods.

Targeted theranostics is another essential part of cancer treatment (chemo- and radiotherapy) and aptamers have emerged as the future anticancer agents due to their distinct characteristics.

A large number of molecules responsible for tumor progression and metastasis that are present at multiple sites can be targeted by aptamers. Being safe and high-affinity therapeutics,

aptamers are competent in treating cancer clinically and thus provide an excellent opportunity to personalize medicine for cancer patients. In future, the main focus should be on the

development and design of aptamers for other molecular targets, in addition to the optimization of existing aptamers. Aptamers can be combined with a variety of nanocarriers, with one or