Exploring the effects of modality and variability on efl learners’ pronunciation of english diphthongs: a student perspective on hvpt implementation

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Recognizing the importance of effective pronunciation training for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners is paramount for improving their comprehensive language proficiency

and communication skills. This study investigated the influence of High Variability Pronunciation Training (HVPT) with and without captions, on the accuracy of English diphthong

pronunciations among Saudi EFL learners. A total of 56 undergraduate EFL learners participated in the study, undergoing multiple sessions of high-variability (HV) and low-variability (LV)

pronunciation training. Various assessments were conducted to measure the learners’ performance, including pretests, posttests, generalized tests, and delayed tests. Additionally, a survey

was conducted to gain insights into the participants’ perceptions of using YouGlish, a multimodal tool, as part of the training process. Data analysis used statistical techniques such as

_t_-tests, ANOVA tests, and descriptive and inferential statistics. The findings indicate that both HV and LV improved the learners’ performance in English pronunciation, regardless of

captioning. LV without captions consistently yielded the highest scores. The students also had positive perceptions of YouGlish as a multimodal tool. These results offer valuable insights

into the efficacy of HV and LV in facilitating EFL learners’ speech production and offer implications for educators and practitioners involved in designing effective instructional strategies

for enhancing EFL learners’ pronunciation skills. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A SCIENTOMETRIC STUDY OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED PRONUNCIATION TRAINING IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION:

TECHNOLOGICAL AFFORDANCES AND RESEARCH TRENDS Article Open access 27 March 2025 INTERNATIONAL INTELLIGIBILITY OF ENGLISH SPOKEN BY COLLEGE STUDENTS IN THE BASHU DIALECT AREA OF CHINA Article

Open access 10 May 2024 PRONUNCIATION INSTRUCTION IN THE CONTEXT OF WORLD ENGLISH: EXPLORING UNIVERSITY EFL INSTRUCTORS’ PERCEPTIONS AND PRACTICES Article Open access 27 June 2024

INTRODUCTION The significance of pronunciation training in the context of foreign language acquisition is not overstated and, hence, should not be disregarded, as it holds a pivotal position

in both the acquisition process and the evaluation of speaking skills and oral proficiency. Foreign language learners encounter various pronunciation challenges stemming from a range of

factors such as limited exposure to the language, perceptual biases, time constraints, and the influence of their native tongue (Fouz-González 2015). One particular area where non-native

English speakers often face difficulties is in identifying and articulating English vowels. This challenge is prevalent among speakers of various languages, including French (Iverson et al.,

2012), Spanish (Iverson and Evans, 2007), German (Iverson and Evans 2007), Japanese (Nishi and Kewley-Port, 2007), and Greek (Lengeris and Hazan 2010). English learners of Arab origin also

confront challenges in vowel production, hence underscoring the importance of pronunciation training for them to master the sounds of English vowels. The acquisition of proficient vowel

pronunciation necessitates the use of diverse methodologies and approaches. These methodologies can be integrated with technological tools to offer several instructional strategies for

teaching pronunciation. Research conducted in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) has highlighted the advantages associated with specific training methods. One particular

method that has garnered attention is High-Variability Phonetic Training (HVPT). HVPT exposes EFL learners to sounds produced by multiple speakers, enhancing their ability to recognize and

accurately reproduce these sounds (Thomson 2018). It has been observed that when pronunciation training explicitly addresses both sound perception and sound production, learners can make

significant improvements in these areas (Alshangiti 2015; Nagle and Baese-Berk 2021). While the implementation of HVPT to enhance speech production has been widely explored, it is noteworthy

that the existing HVPT studies have primarily focused on consonants (e.g., Bradlow, et al. 1997; Lively, et al. 1993; Logan, et al. 1991; Hutchinson 2022). Little attention has been given

to how HVPT can be applied to train learners in vowel production. Some studies have delved into the benefits and challenges of using HVPT, along with the integration of visual aids, for

learning languages such as French and Mandarin Chinese (Hutchinson 2022; Wei et al. 2022). This study aimed to fill this gap in the field of EFL. Specifically, the current research

investigated the impact of HVPT, considering the presence or absence of captioning, on enhancing vowel production among Arab EFL learners through video-based instruction. Research in the

field of speech production training has given rise to concepts for modeling speech using speech technology (Livescu et al. 2016). In the context of EFL education, videos have become a

prevalent resource for delivering authentic input. Videos offer the advantage of motivating learners to actively engage and apply their speaking skills (Bajrami and Ismaili 2016). However,

despite the widespread adoption of videos in EFL classrooms, most of these materials still primarily position learners as passive viewers or recipients of knowledge (Bakar et al. 2018; Fu

and Yang 2019). To help learners be more active while learning pronunciation, some websites, such as YouGlish, are useful in providing language learners with interestingly engaging authentic

videos. Additional research is needed to explore the potential of YouGlish as a tool for demonstrating pronunciation. Topal’s (2023) systematic review delves into the effectiveness of

YouGlish as an instructional aid for second language (L2) pronunciation. The review underscores the importance of further investigations to gain valuable insights into the successful

utilization of YouGlish in teaching various aspects of English pronunciation, including individual sounds and overall speech patterns. It also highlights the necessity of assessing how

YouGlish influences vocabulary retention and learning in diverse educational settings and contexts. There are uncovered questions regarding the influence of HVPT and captioning modalities

for learning sounds via YouGlish. Therefore, it is the purpose of this study to investigate the influence of HVPT and captioning on the accuracy of English speech production, more

particularly English diphthongs, via YouGlish, among Saudi EFL learners. This study answers the following research questions: RESEARCH QUESTIONS RQ1. Do modality and variability of phonetic

training interact to affect EFL learners’ pronunciation of English diphthongs? RQ2. What are the students’ perceptions of using HVPT in learning the pronunciation of English diphthongs?

LITERATURE REVIEW SPEECH PRODUCTION TRAINING Researchers have studied learners’ behaviors when the latter receive various types of speech training in which the quantity, type, and timing of

information are precisely regulated to understand the mechanisms behind speech learning. Different speech training approaches, such as explicit versus incidental and single-modal (language

form only) versus dual-modal (language and meaning), have been investigated, and they were found to produce various learning processes and outcomes in the field of L2 grammar and vocabulary

(Lyster and Saito 2010; Uchihara et al. 2019). In real-world L2 speech learning, learners must pay attention to the visual and motor aspects of sounds, such as the lips, eyes, and movements

of the speaker (multimodal learning). Beginners prioritize learning meaning over accurate production, which means that the more advanced learners become the more attention they pay to

production (Saito et al. 2022). This may suggest that the multimodality training of speech production, such as the availability of captioning, becomes less prioritized by advanced learners.

The investigation of multimodal speech training approaches in the existing literature reveals a prevalent use of videos by educators and researchers, as emphasized in the subsequent

sub-sections. USING VIDEOS FOR AIDING SPEECH PRODUCTION INSTRUCTIONAL PLANNING Recent research undertaken in different EFL contexts has investigated the efficacy of videos as instructional

resources for improving speaking skills, including pronunciation (e.g., Alzahrani and Alqurashi 2023; Ayyat and Al-Aufi 2021; Hakim 2016; Saed et al. 2021), suggest that videos have

demonstrated effectiveness in developing the speaking skills of EFL learners. In these video-based educational settings, Hadijah and Shalawati (2021) found that the use of videos stimulated

and facilitated the acquisition of the target language, making the learning experience more captivating and engaging for students. Alkathiri (2019) conducted a study on Saudi students

participating in a linguistics program on YouTube. The findings revealed that YouTube videos had a positive impact on students’ confidence in public speaking, comprehension of course

material, and engagement in classroom activities. The study also showed that participants improved other skills such as structuring ideas during speech, fluency in spoken English, and the

ability to deduce the meanings of unfamiliar terms. The effectiveness of videos in enhancing pronunciation is influenced by several factors. For example, the choice of video plays a role in

how students perceive speech. Rahayu et al. (2020) observed that animated films were more effective in improving students’ pronunciation skills compared to regular movies. Besides, the level

of instruction, as highlighted by Spring et al. (2019), is associated with the expected improvement in oral fluency. The duration of video-based practice is also another element for

consideration. According to Spring et al. (2019), there exists a significant relationship between the duration of video practice and a decrease in instances of speech pauses. Their study

also demonstrated a positive association between students’ satisfaction with the programs and notable improvements in their oral fluency skills. Wisniewska and Mora (2020) observed that the

inclusion of subtitles and the focus of attention (either toward phonetic form or meaning) while watching videos had an impact on the improvements in pronunciation. That said, the

incorporation of videos into language teaching requires careful instructional planning. Certain researchers have cautioned that students might easily drift into passive video consumption for

entertainment purposes if active learning is not facilitated through well-structured instructional planning (Fisher and Frey 2015). Essentially, the absence of instructional planning can

hinder the effectiveness of using videos as a tool for language learning. When objectives and related activities are not clearly defined, students may not fully engage with the content and

might miss valuable opportunities for meaningful language practice and skill development. To this end, educators should meticulously curate and select videos that align with specific

language learning objectives. This ensures that learners are exposed to relevant and authentic language input, which will ultimately enhance their overall language proficiency. Providing

clear instruction and guidance to learners while incorporating videos as a learning tool is a pivotal element in the process of ensuring effective language acquisition. Galán Cherrez et al.

(2018) support such a claim by concluding that videos can yield positive outcomes if appropriately scaffolded tasks are designed and implemented. VIDEO CAPTIONING AND PRONUNCIATION Using

video captions as an instructional tool for teaching pronunciation can be highly effective for language learners. Captions offer visual support, assisting learners in linking texts to their

corresponding sounds. When students watch captioned videos, they can observe how words are pronounced and follow the speaker’s intonation and stress patterns while simultaneously viewing the

written texts in the videos. Several studies have explored the impact of video captioning on L2 pronunciation development and acquisition. Mitterer and McQueen (2009) investigated whether

English captions or Dutch subtitles could assist learners in comprehending foreign-accented speech, specifically Australian and Scottish accents. Dutch native speakers were divided into

groups that watched videos featuring Scottish-accented speech with English captions, Dutch subtitles, or no text. Another set of groups watched videos with Australian accents, accompanied by

English captions, Dutch subtitles, or no text. After viewing these videos, the participants were asked to mimic 160 audio excerpts from the videos and new ones from the same speakers. The

results revealed that English captions were more effective in helping students adapt to the regional accent and even pronounce new words. On the other hand, Dutch subtitles aided in word

recognition yet hindered the recognition of new words. Similarly, Bird and Williams (2002) examined whether the presence of video captions could help learners associate written words with

their spoken forms. They found that bimodal input, which in their context entails the combination of videos and captioning, significantly improved retention of the phonological forms of

spoken words, as demonstrated by synchronized video captions. Captioning also facilitated the recognition memory of spoken words and non-words compared to a single mode. Wisniewska and Mora

(2018) investigated the impact of English captioned videos on students’ pronunciation improvement. The learners watched video excerpts featuring conversations between characters and were

then asked to read 30 sentences with 7–19 syllables immediately after viewing. Eye movements during video viewing were recorded using eye-tracking technology. The participants were also

presented with non-words and part-words and asked to identify words from non-words. The findings revealed that captioned videos significantly helped L2 learners improve their English

pronunciation and enhanced their ability to identify non-words and part-words. The proficiency level of L2 learners played a crucial role in distinguishing their segmentation skills.

Furthermore, Mohsen and Mahdi (2021) found that the captioning group outperformed the group without captions in pronunciation tests. Interestingly, the performance of the partial captioning

group was slightly higher than that of the full captioning group, although this difference was not statistically significant. In sum, extensive research in L2 literature has consistently

shown that captioning plays a significant role in facilitating L2 vocabulary acquisition, word recognition, and word production. Captioning, as a visual tool, has been extensively studied in

the context of researching L2 speech. However, research findings vary in terms of the relationship between captioning and learners’ proficiency levels. Mahdi and Al Khateeb (2019) concluded

that captioning was particularly suitable for beginners and intermediate-level learners. Conversely, Kim (2020) asserted that both low- and high-level learners derived benefits from

captioning for improving their speech. In contrast, Wisniewska and Mora (2020) argued that captioning was not necessary when the focus was on phonetic forms. They attributed this to the

cognitive load that arises when learners need to simultaneously concentrate on both captions and phonetic forms. APPROACHES TO PHONETIC TRAINING High Variability Phonetic Training (HVPT) and

Low Variability Phonetic Training (LVPT) are two distinct approaches used in phonetic training to enhance learners’ ability to perceive and produce non-native speech contrasts (Brekelmans

et al. 2022). HVPT involves exposing learners to a wide range of acoustic variations of the target phonetic contrasts. This can be achieved by utilizing training stimuli that consist of

multiple talkers producing the target sounds. On the other hand, LVPT focuses on providing learners with a more consistent and controlled learning experience. It typically involves using

stimuli produced by a single talker, ensuring that learners are exposed to a narrow range of acoustic variations for the target sounds. In other words, while HVPT contexts expose

participants to the same set of word/words produced by multiple speakers, LVPT contexts expose participants to listening to a set of word/words produced by the same speaker. HVPT is commonly

utilized to enhance learners’ abilities in both pronunciation and the comprehension of spoken language. HVPT provides a range of benefits for language learners, encompassing the improvement

of pronunciation, speech perception, phonemic sensitivity, and overall language competence (Thomson 2018). Furthermore, HVPT has demonstrated its effectiveness across various age groups, as

exemplified by research conducted by Giannakopoulou et al. (2017). Moreover, this approach is versatile in its application, proving effective in both online and classroom learning

environments, as evidenced by studies such as Thomson (2016). Although LVPT contexts are less commonly used in EFL or ESL learning contexts, they still provide useful insights for educators

as researchers claim that in some particular contexts, ESL learners can discriminate vowels easily when utilizing LVPT (Alshangiti et al. 2023; Georgiou 2021). To investigate HVPT and LVPT,

Wong (2012) conducted experimental research comparing the effectiveness of both on ESL learners’ vowel production and perception—in particular, the focus was on two vowels only. The results

revealed that the HVPT groups outperformed the LVPT in both production and perception. In terms of participants’ perceptions, Wong argued that HVPT groups had a better opportunity to select

from greater options as they were exposed to several speakers unlike LVPT groups who had limited exposure to the vowels, and thus, their perceptions were restricted according to that one

speaker. As a result, Wong claimed that such perceptions among both HVPT groups and LVPT groups shaped their production which, in turn, had the HVPT groups excel in their production compared

to the latter groups. Unlike Wong (2012) who claims that HVPT is more beneficial compared to LVPT, Alshangiti et al. (2023), suggest that LVPT could be slightly more beneficial when

compared to HVPT, especially among young EFL learners. In their experimental study, Alshangiti et al. (2023) exposed young EFL learners, whose ages ranged from 9 to 12 years old, to Audio

and Video Stimuli comparing HVPT groups to LVPT groups. In contrast to Wong (2012), who utilized only two vowels, Alshangiti et al. (2023) exposed their participants to 18 vowels.

Interestingly, their findings suggest that LVPT is indeed an effective tool among young EFL learners. After training, participants’ production and perceptions in LVPT groups showed a slight

advancement when compared to the HVPT. Nonetheless, the researchers claim that such subtle advancement may not be generalized due to their limited number of training sessions and the number

of vowels presented. Their overall results also suggest that LVPT groups exceeded in vowel discrimination and intelligibility whereas HVPT groups displayed better results in their phonetic

cue levels. The effectiveness of HVPT has been extensively studied in the context of EFL learners acquiring English sounds, with participants from various language backgrounds including

Japanese (e.g., Bradlow et al. 1997), Chinese (e.g., Cheng et al. 2019), French (Iverson et al. 2012), and Greek (e.g., Giannakopoulou et al. 2017). Except for the research conducted by

Wiener et al. (2020), these studies primarily focused on individual sounds using minimal pairs as part of the training. The results from these studies also provided some indications that the

effectiveness of HVPT could be substantial and have lasting effects, particularly demonstrated in the delayed posttests conducted six months after the training, as observed in the work of

Leong et al. (2018). Notably, some scholars have argued that successful HVPT is attributed to the explicit nature of the training, which includes trial-by-trial feedback, as proposed by

McCandliss et al. (2002). During the training sessions, participants were able to fully concentrate on a single task, which involved phonetic analysis of each stimulus, without dividing

their cognitive resources among other activities. In HVPT, learners are extensively exposed to new and partially acquired L2 sounds within various phonetic, lexical, and speaker contexts,

aiming to establish generalizable speech categories in the L2. Students typically recognize L2 sounds in small pairs for each token, followed by feedback. HVPT has been shown to generate

positive perceptions among learners (Fouz-González and Mompean 2021). However, it’s worth noting that some studies acknowledge the limitations of the HVPT approach. Wiener et al. (2020), for

example, proposed that HVPT should be complemented with explicit instruction. Similarly, Fletcher and Tobias (2005) emphasized that both the learning and comprehension of L2 learners

improve when combining words and visuals. One of the aspects of HVPT is the use of captioning. The previous studies illustrated that the combination of HVPT with captioning can lead to

significant improvements in learners’ pronunciation skills. For instance, Wei et al. (2022) explored the integration of auditory tones, visual tone effects, and HVPT among Mandarin learners,

demonstrating that this approach enhanced sound recognition. It is important to note that this particular study primarily focused on perceptual improvements in Mandarin. However, there is

currently insufficient empirical evidence within the field of EFL to substantiate the advantages of combining HVPT and visual aids like captioning for pronunciation enhancement. To combine

video captioning and HVPT, some websites have been developed. YouGlish is an example of a website that integrates HVPT with video captioning. YOUGLISH YouGlish, an online tool that promotes

discovery-based and data-driven learning, has emerged as an innovative video-based approach for teaching and enhancing pronunciation. This platform serves as an online repository of numerous

authentic videos, functioning as a personalized phonetic concordancer with the support of teachers. It allows learners to access real-world examples of linguistic performance. YouGlish is

part of the latest generation of computer-assisted pronunciation training tools that utilize genuine audio-visual resources to facilitate individualized and stress-free pronunciation

instruction in educational settings (Topal 2023). YouGlish offers audio demonstrations of authentic English pronunciation sourced from conversations on YouTube. Moreover, it provides

illustrations for different English accents, including American, British, and Australian English. To assist learners in better-grasping phrases or segments, they have the flexibility to

adjust video playback speeds, choosing between normal, slower, or faster options (Barhen 2019). These features empower learners to acquire new words or phrases promptly and with precise

pronunciation. By altering the pace of speech, learners can also identify the stress patterns used in pronunciation. YouGlish is a versatile tool that combines personalized features with

teacher support, making it an ideal choice for fostering discussions. Cox et al. (2019) developed an online resource guide aimed at supporting ESL instructors, specifically those lacking

formal experience in pronunciation instruction, in quickly accessing online video materials that enhance their students’ pronunciation skills. Kartal, Korucu-Kış (2020) study on Turkish

pre-service teachers found that YouGlish proved to be an effective method for teaching pronunciation and improving the retention of commonly mispronounced English words. Furthermore, Anita

(2019) concludes that employing instructional scaffolding can be perceived as beneficial in helping students approximate control over spoken English and actively engage in the learning

process. PRONUNCIATION OF ENGLISH DIPHTHONG (WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO ARAB EFL LEARNERS) A diphthong can be defined as a vowel sound in which there is a single noticeable change in quality

perceivable within a syllable, as exemplified in English words like “beer,” “time,” and “loud” (Crystal 2018). Diphthongs are distinctive because they involve a smooth transition between two

vowel sounds within a single syllable. Among all speech sounds, vowels pose particular challenges for individuals learning a second or foreign language (Schwartz et al. 2016). Consequently,

the inaccurate production of non-native speech sounds, such as English sounds for Arab learners of EFL, may arise from their difficulty in distinguishing between these distinct speech

sounds (Evans and Alshangiti 2018). Arabic and English possess distinct phonological systems, which give rise to specific pronunciation challenges for Arab learners of EFL when dealing with

English diphthongs. In comparison to English, Arabic features a more limited vowel system, as noted by Al-Saqqaf and Vaddapalli (2012). Consequently, Arab learners may encounter difficulties

in accurately distinguishing between various English diphthongs. Arabic’s vowel system comprises a smaller number of phonemes, some of which exhibit multiple allophones that have

corresponding equivalents in English. However, due to the restricted phonetic context in Arabic, Arab learners of English often struggle to equate these sounds with their English

counterparts. For instance, many Arab students may experience challenges in correctly producing the appropriate vowel quality in a minimal pair like “fair” and “fear,” even though both vowel

sounds exist in Arabic. This difficulty arises because, in the phonological system of Arabic, both vowels are considered a single vowel phoneme (/eə/). The following subsection explains

positioning this study within the theory of cognitive load. THE THEORY OF COGNITIVE LOAD The Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) was proposed by Sweller (1988). This theory is based on generating

instructional and experimental effects on human cognition for generating knowledge and skills that are taught. The outcomes of these effects are compared with outcomes that emerge from

traditional implementations. Sweller’s proposition is based on the working memory theory, which suggests that long-term memories develop the processing and expansion of both auditory and

visual information. If learners are introduced to complex information, the formation of new memories will be hindered. CLT serves as a theoretical framework for comprehending the performance

of participants across different conditions in the task. CLT refers to the amount of mental effort required to process information and perform a task. In the current study, the authors

examined how the manipulation of phonetic variability and the presence of captions influenced participants’ performance, considering the cognitive load imposed by these factors. METHODS

RESEARCH DESIGN In this study, an experimental design was employed to investigate EFL students’ pronunciation of English diphthongs. The treatment in this investigation included several high

and LV multimodal sessions as tools to train EFL students’ pronunciation. In addition, the experiment utilized a pretest, a posttest, a generalized test, and a delayed test; a survey was

also conducted to further examine the participants’ perceptions. PARTICIPANTS The present study employed a sample of 56 Saudi undergraduate female students majoring in English Language.

Initially, participants were 64; however, due to attrition resulting from student withdrawals from the course, the final sample was reduced to 56 individuals. The participants were enrolled

in level two English listening and speaking courses, which corresponds to the second semester of first-year courses at a public university located in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi

Arabia. As a prerequisite for admission to the university, all Saudi students were mandated to achieve a score of 60 or higher on the Standardized Test of English Proficiency (STEP). Given

that the students were taking their second listening and speaking course, their Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) level was assumed to be at the B2 level. All

participants agreed to participate voluntarily, and their ages ranged from 18 to 24. CONTEXT Data were collected during the third trimester of the academic year 2023 throughout 13 weeks. The

participants were divided into four groups: LV no captions, HV no caption, HV and captions, and LV and caption. As explained earlier in this paper, HV in this context refers to multiple

speakers pronouncing the same word whereas LV refers to listening to one speaker pronounce the word multiple times. That is, in the latter the LV groups listened to the same speaker repeat

the word several times (6 times) while the HV groups listened to different speakers (6 speakers) pronounce the same word in multiple contexts. The selection of students for each group

followed a random sampling criterion as each group represented a section in a Listening and Speaking course. All data was collected during the lectures of the course as all 56 participants

were studying this course. Data was collected in person by the researchers inside a formal classroom during the time of lectures at a public university in Saudi Arabia. Tests were

administered and recorded individually in a soundproof classroom. DATA COLLECTION TOOLS PRETEST, POSTTEST, GENERALIZATION TEST, DELAYED TEST, AND SURVEY In the present study, three

diphthongs (/əʊ/, /aʊ/, and /aɪ/) were targeted for assessment of students’ pronunciation. Each diphthong was represented by five minimal pairs, resulting in a total of 15 minimal pairs.

Minimal pairs are pairs of words that differ in only one sound, in this case, the diphthong being assessed. To assess students’ pronunciation, individual test sessions were conducted with

each participant. During these sessions, the participants were asked to read a list of minimal pairs while recording themselves on their mobile devices. After recording, the students were

instructed to upload the recorded audio files to an online form for evaluation. This method facilitated the collection and centralized storage of the audio files for later analysis. It also

facilitated an objective evaluation of the students’ pronunciation performance while minimizing potential biases introduced by subjective evaluations. To clarify the testing process, each

student was required to submit four audio files. These files corresponded to different stages of the study, including the pretest, posttest, generalized test, and delayed test. The pretest

was administered prior to any training to establish the students’ baseline proficiency level, while the posttest was given after the training to assess their progress. The generalized test

was conducted to evaluate the transferability of the acquired skills to new contexts and included five new minimal pairs not previously encountered. These additional five minimal pairs were

specifically designed to test the generalization of pronunciation skills beyond the trained minimal pairs. Finally, the delayed test aimed to measure the retention of the skills over time.

PERCEPTION TEST The perception test involved presenting participants with a list of minimal pairs that were randomly arranged. A native English speaker pronounced one word from each pair.

Subsequently, the participants were asked to select the word that they heard from each minimal pair. The purpose of this test was to ensure that participants could correctly perceive and

differentiate between the target words in the minimal pairs, regardless of their own pronunciation abilities. It helped determine whether any mispronunciations during the pronunciation

assessment were due to actual pronunciation difficulties rather than a lack of knowledge of the word itself. The use of a native English speaker ensured that the minimal pairs were

pronounced accurately and consistently, while the random arrangement of the pairs minimized potential biases introduced by the order of presentation. The participants’ responses were

submitted using Google Forms and analyzed to evaluate their accuracy in identifying the correct word from each minimal pair. SURVEY The survey included two parts. The first part collected

demographic information from participants, such as age, nationality, and self-reported English language proficiency level. The second part of the survey aimed to understand participants’

perceptions of how YouGlish assisted their English pronunciation. This part followed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The survey was based on a survey

written by Fu and Yang (2019); however, to ensure content validity, the questionnaire underwent a review process by a panel of five EFL instructors who specialized in applied linguistics.

Based on their feedback, several adjustments were made; some items were modified, four items were removed, and seven items were added. For example, the original item “YouGlish assists me in

acquiring English pronunciation without my teacher’s help” was modified to “YouGlish assists me in acquiring English pronunciation” and “YouGlish assists me in acquiring English intonation

without my teacher’s help” was replaced with “YouGlish assists me in acquiring pronunciation of English vowels”. Items related to language learning in general in the original survey were

removed since they are irrelevant to the current study’s objectives. Other items related to the features of YouGlish were added such as listening to different accents, listening to various

speakers, using the replay button, reading the captions, and adjusting the speed. Following these revisions, the questionnaire was converted into an electronic format and distributed among

participants. PROCEDURE Pretest, Post, generalized, and delayed tests and a final survey were the tools utilized in this experiment. However, prior to the experiment, a pilot was conducted

by recruiting 15 level two students who were randomly selected. This was to expose the students to the words before the actual experiment and support the validity of lists used to measure

students’ pronunciation. As a result of the pilot, some words were eliminated from the experiment as most of the participants pronounced them correctly. In addition, the order of the

diphthongs was adjusted in the actual experiment since students followed a pattern of rhyme with the minimal pairs in the pilot as they pounced the words in a minimal pair list. As a result,

and to avoid such incidents, the lists of words for the experiment were adjusted accordingly. During the pretest phase, participants’ perceptions were measured by asking participants to

select the minimal pair that was pronounced by the native English speaker. The list of words included some distracting diphthongs to avoid any rhyming patterns that may have occurred with

the pilot. Again, to minimize potential biases, participants were asked to mark the correct word as the speaker pronounced it using an electronic form. As for the pretest, students’

pronunciation of the diphthongs/əʊ/, /aʊ/, and/aɪ/were measured by having them pronounce 15 minimal pairs and record their pronunciation. One week after the participants’ initial recording

(pretest), students were exposed to the diphthongs as the words were pronounced by native speakers from videos all of which were retrieved from the website YouGlish.com. All native speakers

were following an American English accent. For each group, LV no caption, HV no caption, HV and caption, and LV and caption, the participants were asked to pay attention to the proper

pronunciation of each word and read the highlighted caption in the case of the captioned group. Participants were exposed to three training sessions: the first training session was a list of

videos including the diphthongs /əʊ/ and /aʊ/, second training session was a list of videos including the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /əʊ/; and finally, the third training session was a list of

videos including the diphthongs/aɪ/and/əʊ/(see Table 1). After completing all three training sessions and exposing the participants to the diphthongs by watching the YouGlish videos, a

post-test and a generalization test were administered for all groups. Similar to the pretest, participants followed the same criteria in recording their pronunciation; however, different

words were provided for the generalization test. In addition, two months after the posttest, the delayed test was administered following the same criteria. This means that each student

underwent a total of four testing sessions. As a result, 224 audio files were compiled from the participants in general. All the audio files were evaluated by three professors who hold a

Ph.D. in applied linguistics. Each evaluator listened to the participant’s pronunciation independently without getting affected by the other evaluators and marked each word with 0 or 1 (0 =

incorrect, 1 = correct). After that, evaluations were collected and combined in one form for data analysis. By having multiple evaluators independently assess the same recordings, the study

can measure the level of agreement among evaluators. When there is high agreement, it reduces the influence of individual biases. Further, the evaluators’ specialized knowledge and training

in applied linguistics provide a common framework and criteria for evaluating pronunciation accuracy, reducing the impact of personal biases. In cases of discrepancies, the evaluators engage

in discussions to reach a consensus, ensuring evaluations are based on shared understanding and criteria. After the delayed test, and to further analyze the participants’ perceptions,

students completed a survey to understand how YouGlish assisted their English pronunciation. DATA ANALYSIS To comprehensively address the research questions posed in this study, we conducted

a rigorous analysis of the students’ pronunciation test scores both before and after the intervention. This analysis played a pivotal role in evaluating the effectiveness of the

intervention in improving pronunciation skills. To address the first research question specifically, we meticulously examined the data using an independent-sample _t_-test. This statistical

approach enabled a direct comparison of scores obtained by participants in the four distinct groups before and after the intervention, aiming to uncover any significant differences in

pronunciation skills both within and between these groups. For the second and third research questions, we conducted a more comprehensive analysis using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA

test. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA is a statistical technique used to analyze the effects of two independent variables within the context of a repeated measures design. This statistical

technique was employed to explore differences in total mean scores among the four groups and determine the statistical significance of these variations. All these analyses were conducted

using SPSS version 27. RESULTS MODALITY, VARIABILITY, AND EFL LEARNERS’ DIPHTHONG PRONUNCIATION A repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to answer the first research question aimed at

exploring whether there were any significant differences in the scores of the students’ pronunciation test per modality and variability. First, descriptive analysis was performed as shown in

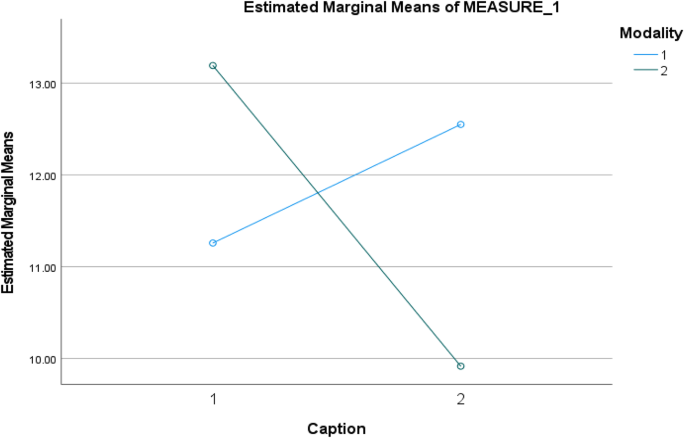

Table 2. The results in Table 2 showed that the mean of low variability with no caption was 11.25 with SD = 3.99 and the mean of low variability with caption was 13.19 with SD = 2.10. For

high variability with no captions, the mean was 12.55 and SD = 1.97, and high variability with caption reported a mean of 9.91 and SD = 1.56. This analysis yielded significant main effects

for caption, modality, and the interaction of both, as can be seen in Table 3, also visually displayed in Fig. 1. Results for the repeated-measures ANOVA analysis on scores for captions

yielded significant differences for both groups F(1, 29) = 22.55, _p_ = 0.000, partial η2 = 0.159. Results for the scores of modality yielded non-significant differences for both groups F(1,

29) = 2.07, _p_ = 0.153, partial η2 = 0.01. To find out the difference between high variability and low variability when they are incorporated with captioning and no captioning, Pairwise

Comparisons of Pronunciation Scores were analyzed as shown in Table 4. Post hoc analyses showed a significant difference between low caption and high no caption groups (_p_ = 0.000) and

between high caption and low no caption groups (_p_ = 0.000). When captions were present, there was a significant mean difference of 0.992 between low and high variability conditions. The

_p_-value was 0.000 suggesting a significant difference between low and high variability conditions with captions. Also, in the absence of captions, the mean difference was −0.992 between

high and low variability conditions. The _p_-value was 0.000 indicating a significant difference between high and low variability conditions without captions. STUDENT PERCEPTIONS OF HVPT FOR

LEARNING ENGLISH DIPHTHONG PRONUNCIATION The second research question was about whether there was a difference in the participants’ perceptions of using HVPT in learning the pronunciation

of English diphthongs. To find out this perception, descriptive and inferential statistics were performed. First, the reliability of the questionnaire was checked. The Cronbach’s Alpha was

0.80 which indicated demonstrate acceptable reliability (Howitt, and Cramer 2008). To find the difference between the four groups in the total means, an ANOVA test was performed. The results

are shown in Table 5. Table 5 shows the results of the total means of the participants’ perceptions. The mean was 3.94(SD = 0.379) for the LV no caption. The mean was 3.98 (SD = 0.345) for

the HV no caption group. The mean was 4.13 (SD = 0.55) for the HV and caption group. The mean was 4.31 (SD = 0.453) for the LV and caption group. The results revealed that there was no

significant difference in the total means of the participants’ perceptions of the four groups (f = 2.30, _p_ = 0.08). The mean scores for all groups were above 3.0, with the highest mean

score observed in the LV and caption group (4.31). While the statistical analysis did not find a significant difference among the groups, it is important to note that the mean scores

themselves suggest a generally positive perception across all conditions. The relatively high mean scores, along with the absence of a significant difference, indicate that participants in

all groups had favorable perceptions of using YouGlish for English pronunciation acquisition. DISCUSSION The results of the current study provide insights into the impact of HVPT, captioned

and non-captioned videos, on learners’ performance and perceptions in acquiring English diphthongs in EFL settings. The results indicate that both HV and LV affected learners’ performance

regardless of whether the videos were captioned or non-captioned. This result is in line with many studies indicating the positive impact of videos on learners’ acquisition of the target

language (Alzahrani and Alqurashi (2023); Ayyat and Al-Aufi 2021; Hakim 2016; Saed et al., 2021). In terms of comparing the different conditions, the LV and caption condition showed the

highest increase, followed by HV no caption, LV and caption, and finally HV and caption. The mean score for the LV and caption condition is 13.19. Comparing it to the Low Variability without

caption condition, an improvement in participants’ performance was observed when captions were present. The inclusion of captions likely provided additional support and guidance, leading to

higher scores. Consistent with prior research (Bird and Williams 2002; Mitterer and McQueen 2009; Mohsen and Mahdi; 2021; Wisniewska and Mora 2018), the present study’s findings align with

the evidence that captioned videos significantly contribute to the improvement of English pronunciation among L2 learners. Moreover, the findings suggest that the combination of LV and

captions may have facilitated a focused and consistent learning experience, thereby reducing extraneous cognitive load and enhancing learning. This observation aligns with the Cognitive Load

Theory proposed by Sweller (1988), which posits that reducing extraneous cognitive load can promote effective learning. In the present context, the utilization of captions alongside LV may

have contributed to a reduction in cognitive load by providing learners with a concentrated and uninterrupted learning environment. The absence of different speakers in the stimuli likely

compelled learners to allocate their attention to both the auditory input and the accompanying captions, thereby enhancing their capacity to discriminate and process phonetic information.

Following the LV with captions group, the HVPT without captions group showed the second-highest scores in performance. The mean score for this condition is 12.55. In comparison to the LV

without caption condition, this suggests a slightly better performance when participants were exposed to a wider range of phonetic variations (i.e., different speakers) without captions.

This finding is in line with the study by Fouz-González and Mompean (2021), which suggests that HVPT can lead to positive perceptions among learners. However, the HVPT without caption

improvement compared to LV without caption is not as significant as expected and therefore aligns with the conclusions drawn by Wiener et al. (2020) and Fletcher and Tobias (2005), who

emphasize that relying solely on HVPT may not be adequate for maximizing learning and comprehension. These studies propose that incorporating explicit instruction alongside HVPT can yield

more substantial improvements in terms of learning outcomes and comprehension abilities. Notably, the inclusion of captions seemed to yield lower scores in learner performance, as evident in

the HVPT with the caption group. The mean score for this condition is 9.91. Comparing it to the HVPT without caption condition, a decline in participants’ performance was observed when

captions were added. This suggests that the presence of captions may not have provided as much support in the context of HVPT. It is possible that the participants experienced an increased

cognitive load due to the combination of high variability stimuli and the cognitive processing required to read the captions simultaneously and therefore hindered their ability to comprehend

the English diphthongs. This result contrasts with previous studies reporting that captioning aids pronunciation (e.g., Bird and Williams 2002; Mitterer and McQueen 2009; Mohsen and Mahdi

2021; Wisniewska and Mora 2018). One reason is that in the current study, more input modalities were used (i.e., captioning and variability). This suggests that the effectiveness of captions

may vary depending on the degree of phonetic variability in the stimuli. Furthermore, learning pronunciation is different from learning meaning. More input modalities cause an improvement

in learning a word’s meaning. However, using more input modalities for learning a word’s pronunciation can cause a cognitive load and may hinder learning a word’s pronunciation. This finding

aligns with the perspective of Wisniewska and Mora (2020), who argued that captioning may not be necessary when the primary focus is on phonetic forms. They attributed this to the cognitive

load that arises from attending to both captions and phonetic forms simultaneously. Learners need to process language input in a way that allows them to notice and internalize the language

features they are exposed to. When learners watch videos with captions, their attention may be divided between the spoken input and the written text, leading to cognitive overload. In the

present study, this cognitive overload is evident in the HVPT with the captioning group and it seemed to hinder their ability to discriminate and process phonetic information. It is

important to note that individual learner preferences and learning styles may vary, and some learners may still benefit from using captions with HVPT for other purposes, such as vocabulary

acquisition or comprehension of specific terms. However, the observed result suggests that, in terms of pronunciation improvement, captions with LV may be more beneficial for English

learners. Language proficiency can also influence the findings. For the current study, participants were specifically selected to have an intermediate level of proficiency, corresponding to

a B2 level according to the CEFR for Languages. Hutchinson (2022) and Wei et al. (2022) indicate that captioning integrated with audio tools could be more beneficial for low-proficiency

learners or those without prior knowledge of the target language. Mahdi and Al Khateeb (2019) argue that captioning is more appropriate for beginners and intermediate-level learners, while

Kim (2020) claims that learners at all proficiency levels find captioning beneficial for speech improvement. These contrasting findings highlight the need for further research to determine

the optimal combination of variability and captions for pronunciation training. Finally, the results indicate that all groups showed positive perceptions toward using YouGlish, as a tool for

acquiring English pronunciation. Participants perceived the features of YouGlish, such as listening to different accents, and different speakers, using the replay button, reading the

captions, and adjusting the speed, as beneficial for improving pronunciation in general and vowels in specific. This finding aligns with the study conducted by Kartal, Korucu-Kış (2020),

which demonstrated the effectiveness of utilizing YouGlish as a method for teaching pronunciation and enhancing the acquisition and retention of frequently mispronounced English words.

Discussing the results and their relation to previous studies has several pedagogical implications. First, including visual and audio input can be beneficial in developing learners’

phonological awareness, recognition memory, and overall pronunciation skills as supported by previous studies (Saed et al. 2021; Ayyat and Al-Aufi 2021; Alzahrani and Alqurashi (2023)).

Therefore, educators should consider incorporating multimodal resources and activities into their pronunciation teaching practices. While HVPT aims to enhance learners’ ability to generalize

and discriminate across different talkers and contexts, LVPT prioritizes a more focused and controlled learning environment. The choice between HVPT and LVPT depends on the specific

learning goals, context, and the nature of the target phonetic contrasts being taught. Therefore, researchers and practitioners should continue to explore and evaluate the advantages and

limitations of both approaches in improving non-native speech perception and production. In addition, instructors need to keep in mind the cognitive load students experience when

incorporating multimodality and using various modes of input. Educators may need to carefully select and limit the use of input modalities during pronunciation training. This could involve

gradually incorporating additional modalities as learners progress. Instructors should also explicitly teach learners how to utilize and integrate different modalities effectively to

mitigate the negative impact of excessive input modalities. This may involve guiding learners on how to focus their attention, identify relevant cues, and prioritize certain aspects of

pronunciation. Aside from multimodality and students’ cognitive load, educators need to revisit the approach in which students are trained to pronounce. That is, L2 learners need both: HV

and LV. Although previous research recommended HVPT with consonants (Hutchinson 2022), this study may shed some light on implementing HVPT with vowels. More importantly, considering that

certain findings of the current study deviate from previous research, educators need to approach variability and captions with careful consideration. To maximize effectiveness, educators

should design scaffolding tasks and incorporate explicit instruction into the training process (Anita 2019; Galán Cherrez et al. 2018). The contrasting effects also suggest the importance of

individualizing pronunciation instruction based on learners’ proficiency levels and needs. This approach can help learners comprehensively develop their pronunciation skills and address any

potential challenges that arise from such contrasting findings. Finally, learners’ positive perceptions toward YouGlish highlight the potential of technology in supporting pronunciation

instruction. Instructors can utilize online tools, applications, and platforms to acquaint learners with English accents spoken by individuals from diverse linguistic backgrounds

(Almusharraf 2021). Nonetheless, students’ level, pedagogical goal, and the overall instructional context must align with the selected technology. CONCLUSION This study aimed to examine the

impact of HVPT, with and without captions, on the accuracy of English diphthongs among Saudi EFL learners. The significance of this investigation lies in its potential to shed light on

effective instructional approaches for enhancing EFL learners’ pronunciation skills, particularly regarding the use of videos and captions. The findings of this study indicate that learners’

performance showed improvement with both HVPT and LV, regardless of whether the training videos were captioned or non-captioned. When comparing the various conditions, it appears that the

LV without caption condition consistently demonstrates the highest scores in all assessments conducted (pretest, posttest, delayed, and generalized). This particular condition may have

offered a more focused and consistent learning experience, thereby reducing any extraneous cognitive load and facilitating the learning process. Furthermore, the study revealed positive

perceptions among the students regarding the use of YouGlish as a multimodal tool in their pronunciation training. These results offer valuable insights into the efficacy of HVPT in

facilitating EFL learners’ speech production and further highlight the potential benefits of incorporating multimodal tools, such as YouGlish, in pronunciation training. Furthermore,

effective pronunciation plays a crucial role in language learning and communication, which are topics of interest to scholars in various disciplines. The findings of the current study

contribute to the understanding of how pronunciation training can enhance learners’ language skills, thereby facilitating better cross-cultural communication and language comprehension.

Improving pronunciation has broad applications in fields like language education, applied linguistics, communication studies, and psychology. By investigating the effectiveness of a specific

pronunciation training method, the current study provides insights that can inform language teaching practices and syllabus design, ultimately benefiting language learners worldwide. The

current study has a limited number of participants, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. To address this limitation, future research should aim for a larger and more

diverse sample size to ensure that results can be applied to a wider population. Moreover, the current study has provided a relatively short duration of training (three weeks), which might

not be sufficient for participants to fully benefit from the training methods. Future research could consider extending the training period to assess the long-term effects and sustainability

of phonetic training. Furthermore, the contrasting findings regarding the effectiveness of HVPT alone and the impact of captions on different proficiency levels warrant further

investigation. Future research can explore these areas to provide more conclusive evidence and identify the most effective approaches for pronunciation instruction. Moreover, the results

highlight the importance of considering methodological factors in pronunciation research. Factors such as the inclusion of explicit instruction, the cognitive load introduced by captions,

and the influence of learner proficiency levels should be carefully considered and controlled in experimental designs to obtain more accurate and reliable results. Finally, the positive

perceptions reported by learners towards YouGlish and its features underscore the significance of considering learners’ perspectives in research. Future studies can explore the relationship

between learners’ perceptions, motivation, and engagement in pronunciation training to gain insights into designing effective instructional materials and tools. DATA AVAILABILITY Available

in the supplementary files. REFERENCES * Alkathiri LA (2019) Students’ perspectives towards using YouTube in improving EFL learners’ motivation to speak. J Educ Cult Stud 3(1):12–30.

https://doi.org/10.22158/jecs.v3n1p12 Article Google Scholar * Almusharraf A (2021) Learners’ confidence, attitudes, and practice towards learning pronunciation. Int J Appl Linguist

32(1):126–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.1240 Article Google Scholar * Al-Saqqaf AH, Vaddapalli M (2012) Teaching english vowels to Arab students: a search for a model and pedagogical

implications. Int J Eng Lan Lit 2(2):46–56 Google Scholar * Alshangiti W (2015) Speech production and perception in adult Arabic learners of English: a comparative study of the role of

production and perception training in the acquisition of British English vowels. Dissertation, University College London. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:141516051 * Alshangiti W,

Evans BG, Wibrow M (2023) Investigating the effects of speaker variability on Arabic children’s acquisition of English vowels. Arab World Eng J 14(1):3–27.

https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol14no1.1 Article Google Scholar * Alzahrani SA, Alqurashi HS (2023) Using the flipped classroom model to improve Saudi EFL learners’ English pronunciation.

Ling Cu Re 7(S1):51–71. https://doi.org/10.21744/lingcure.v7nS1.2260 Article Google Scholar * Anita A (2019) Teacher’s instructional scaffolding in teaching speaking to Kampung inggris

Rafflessia Rejang Lebong participants. Al-Lughah: J Bhs 8(2):18–29. https://doi.org/10.29300/lughah.v8i2.2360 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Ayyat A, Al-Aufi A (2021) Enhancing the

listening and speaking skills using interactive online tools in the HEIs context. Int J Ling Lit Transl 4(2):146–153. https://doi.org/10.32996/ijllt.2021.4.2.18 Article Google Scholar *

Bajrami L, Ismaili M (2016) The role of video materials in EFL classrooms. Procedia – Soc Behav Sci 232:502–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.068 Article Google Scholar * Bakar

S, Aminullah R, Sahidol JN, Harun NI, Razali, A (2018) Using YouTube to encourage English learning in ESL classrooms. In: Noor MM, Ahmad B, Ismail M, Hashim H, Baharum MA (Eds.),

Proceedings of the Regional Conference on Science, Technology and Social Sciences (RCSTSS 2016), pp. 415–419. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0203-9_38 * Barhen D (2019)

YouGlish. TESL – E J 23(2). https://tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume23/ej90/ej90m1/ * Bird SA, Williams JN (2002) The effect of bimodal input on implicit and explicit memory: an

investigation into the benefits of within-language subtitling. Appl Psycholing 23(4):509–533. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716402004022 Article Google Scholar * Bradlow AR, Pisoni DB,

Akahane-Yamada R, Tohkura YI (1997) Training Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l: IV. Some effects of perceptual learning on speech production. J Acous Soc Am 101(4):2299–23.

https://doi.org/10.1121/1.418276 Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Brekelmans G, Lavan N, Saito H, Clayards M, Wonnacott E (2022) Does high variability training improve the learning of

non-native phoneme contrasts over low variability training? A replication. J Mem Lang 126:104352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2022.104352 Article Google Scholar * Cheng B, Zhang X, Fan

S, Zhang Y (2019) The role of temporal acoustic exaggeration in high variability phonetic training: a behavioral and ERP study. Front Psychol 10:1178.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01178 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cox JL, Henrichsen LE, Tanner MW, McMurry BL (2019) The needs analysis, design, development, and

evaluation of the “English pronunciation guide: an ESL teachers’ guide to pronunciation teaching using online resources”. TESL – E J 22(4):1–24.

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1204566.pdf Google Scholar * Crystal D (2018) The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language, 3rd ed. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108528931 * Evans

BG, Alshangiti W (2018) The perception and production of British English vowels and consonants by Arabic learners of English. J Phon 68:15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2018.01.002

Article Google Scholar * Fisher D, Frey N (2015) Improve reading with complex texts. Phi Delta Kappan 96(5):56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721715569472 Article Google Scholar *

Fletcher JD, Tobias S (2005) The multimedia principle. In: Mayer RE (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning, pp. 117–134. Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816819.008 * Fouz-González J (2015) Trends and directions in computer-assisted pronunciation training. In: Mompean JA, Fouz-González J (Eds.), Investigating

English pronunciation, pp. 314–342. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137509437_14 * Fouz-González J, Mompean JA (2021) Phonetic symbols vs keywords in perceptual training:

the learners’ views. ELT J 75(4):460–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab037 Article Google Scholar * Fu JS, Yang S-H (2019) Exploring how YouGlish facilitates EFL learners’ speaking

competence. Edu Tech Soc 22(4):47–58 CAS Google Scholar * Galán Cherrez NM, Maya Montalvan JP, Garcia Brito OE, Montece Ochoa SK (2018) Impact of the use of selected YouTube videos to

enhance the speaking performance of A2 EFL learners of an Ecuadorian public high school. RECIMUNDO 2(3):199–226. https://doi.org/10.26820/recimundo/2.(3).julio.2018.199-226 Article Google

Scholar * Georgiou GP (2021) Effects of phonetic training on the discrimination of second language sounds by learners with naturalistic access to the second language. J Psycholing Res

50(3):707–721. https://doi-org.sdl.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s10936-021-09774-3 Article Google Scholar * Giannakopoulou A, Brown H, Clayards M, Wonnacott E (2017) High or low? Comparing high

and low-variability phonetic training in adult and child second language learners. PeerJ 5:e3209. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3209 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Hadijah S, Shalawati S (2021) A video-mediated EFL learning: highlighting Indonesian students’ voices. J-SHMIC 8(2):179–193. https://doi.org/10.25299/jshmic.2021.vol8(2).7329 Article Google

Scholar * Hakim MIAA (2016) The use of video in teaching English speaking (A quasi-experimental research in senior high school in Sukabumi). J Eng Edu 4(2):44–48.

http://ejournal.upi.edu/index.php/L-E/article/view/4631 Google Scholar * Howitt D, Cramer D (2008) Introduction to research methods in psychology, 2nd ed. Prentice Hall, New Jersey *

Hutchinson A (2022) The effect of foreign film on the production and perception of non-native speech. Dissertation, Purdue University. https://doi.org/10.25394/PGS.19424171.v1 * Iverson P,

Evans BG (2007) Learning English vowels with different first-language vowel systems: Perception of formant targets, formant movement, and duration. J Acous Soc Am 122(5):2842–2854.

https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2783198 Article ADS Google Scholar * Iverson P, Pinet M, Evans BG (2012) Auditory training for experienced and inexperienced second-language learners: Native

French speakers learning English vowels. Appl Psycholing 33(1):145–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716411000300 Article Google Scholar * Kartal G, Korucu-Kış S (2020) The use of Twitter

and YouGlish for the learning and retention of commonly mispronounced English words. Edu Info Tech 25(1):193–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09970-8 Article Google Scholar * Kim N

(2020) The effects of the use of captions on low- and high-level EFL learners’ speaking performance. Ling Res 37:135–161. https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.37.202009.006 Article Google

Scholar * Lengeris A, Hazan V (2010) The effect of native vowel processing ability and frequency discrimination acuity on the phonetic training of English vowels for native speakers of

Greek. J Acous Soc Am 128(6):3757–3768. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3506351 Article ADS Google Scholar * Leong CXR, Price JM, Pitchford NJ, van Heuven WJB (2018) High variability phonetic

training in adaptive adverse conditions is rapid, effective, and sustained. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0204888. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204888 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lively

SE, Logan JS, Pisoni DB (1993) Training Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l/. II: The role of phonetic environment and talker variability in learning new perceptual categories. J

Acous Soc Am 94(3):1242–1255 Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Livescu K, Rudzicz F, Fosler-Lussier E, Hasegawa-Johnson M, Bilmes J (2016) Speech production in speech technologies:

Introduction to the CSL special issue. Comput Speech Lang 36:165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2015.11.002 Article Google Scholar * Logan JS, Lively SE, Pisoni DB (1991) Training

Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l: A first report. J Acous Soc Am 89(2):874–886. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1894649 Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Lyster R, Saito K (2010)

Oral feedback in classroom SLA: A meta-analysis. Stud Second Lang Acquis 32(2):265–302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263109990520 Article Google Scholar * Mahdi HS, Al Khateeb AA (2019)

The effectiveness of computer‐assisted pronunciation training: A meta‐analysis. Rev Educ 7(3):733–753. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3165 Article Google Scholar * McCandliss BD, Fiez JA,

Protopapas A, Conway M, McClelland JL (2002) Success and failure in teaching the [r]–(l) contrast to Japanese adults: Tests of a Hebbian model of plasticity and stabilization in spoken

language perception. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2(2):89–108. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.2.2.89 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mitterer H, McQueen JM (2009) Foreign subtitles help but

native-language subtitles harm foreign speech perception. PLoS ONE 4(11):e7785. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007785 Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Mohsen MA, Mahdi HS (2021) Partial versus full captioning mode to improve L2 vocabulary acquisition in a mobile-assisted language learning setting: words pronunciation domain. J Comput High

Educ 33(2):524–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09276-0 Article Google Scholar * Nagle CL, Baese-Berk MM (2021) Advancing the state of the art in L2 speech perception-production

research: Revisiting theoretical assumptions and methodological practices. Stud Second Lang Acquis 44(2):580–605. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000371 Article Google Scholar * Nishi

K, Kewley-Port D (2007) Training Japanese listeners to perceive American English vowels: Influence of training sets. J Speech Lang Hearing Res 50(6):1496–1509.

https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/103) Article Google Scholar * Rahayu F, Dayu AT, Islamiah N (2020) Perception of using movie to promote students’ in recognizing pronunciation.

_Economics and Politics_. Proceedings of SHEP International Conference On Social Sciences y Humanity (pp. 75–78). https://doi.org/10.31602/.v1i1.3979 * Saed HA, Haider AS, Al-Salman S,

Hussein RF (2021) The use of YouTube in developing the speaking skills of Jordanian EFL university students. Heliyon 7(7):e07543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07543 Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Saito K, Hanzawa K, Petrova K, Kachlicka M, Suzukida Y, Tierney A (2022) Incidental and multimodal high variability phonetic training: Potential,

limits, and future directions. Lang Learn 72(4):1049–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12503 Article Google Scholar * Schwartz G, Aperliński G, Kaźmierski K, Weckwerth J (2016) Dynamic

targets in the acquisition of L2 English vowels. Res Lang 14(2):181–202. https://doi.org/10.1515/rela-2016-0011 Article Google Scholar * Spring R, Kato F, Mori C (2019) Factors associated

with improvement in oral fluency when using video-synchronous mediated communication with native speakers. Foreign Lang Ann 52(1):87–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12381 Article Google

Scholar * Sweller J (1988) Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cogn Sci 12(2):257–285 Article Google Scholar * Thomson RI (2016) Does training to perceive L2

English vowels in one phonetic context transfer to other phonetic contexts? Can Acous 44(3):198–199 Google Scholar * Thomson RI (2018) High variability [Pronunciation] training (HVPT): a

proven technique about which every language teacher and learner ought to know. J Second Lang Pronunc 4(2):208–231. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.17038.tho Article Google Scholar * Topal IH

(2023) YouGlish: A web-sourced corpus for bolstering L2 pronunciation in language education. J Dig Edu Tech 3(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.30935/jdet/13236 Article Google Scholar * Uchihara

T, Webb S, Yanagisawa A (2019) The effects of repetition on incidental vocabulary learning: a meta-analysis of correlational studies. Lang Learn 69(3):559–599.

https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12343 Article Google Scholar * Wei Y, Jia L, Gao F, Wang J (2022) Visual–auditory integration and high-variability speech can facilitate Mandarin Chinese tone

identification. J Speech Lang Hearing Res 65(11):4096–4111. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00691 Article Google Scholar * Wiener S, Chan MK, Ito K (2020) Do explicit instruction and

HV phonetic training improve non-native speakers’ Mandarin tone productions? Mod Lang J 104(1):152–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12619 Article Google Scholar * Wisniewska N, Mora JC

(2018) Pronunciation learning through captioned videos. iastatedigitalpress.com. Proceedings of the 9th Annual Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference (pp.

204–215). Iowa State University * Wisniewska N, Mora JC (2020) Can captioned video benefit second language pronunciation. Stud Second Lang Acquis 42(3):599–624.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000029 Article Google Scholar * Wong JW (2012) Training the perception and production of English // and // of Cantonese ESL learners: a comparison of low

vs. high variability phonetic training. Proceedings of the 14th Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology (SST 2012). Sydney, Australia, December 2012 Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University for supporting and funding this project. This work was supported and funded by the

Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-RG23007). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * College of Languages and

Translation, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Asma Almusharraf & Amal Aljasser * Faculty of Language Studies, Arab Open University, Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia Hassan Saleh Mahdi * Department of Foreign Languages, College of Arts, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia Haifa Al-Nofaie * English Language Institute, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi

Arabia Elham Ghobain Authors * Asma Almusharraf View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Amal Aljasser View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hassan Saleh Mahdi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Haifa Al-Nofaie View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Elham Ghobain View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS AA

contributed to research project administration, data collection, wrote the discussion and conclusion sections, and actively participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. AmA was

involved in data collection, took charge of writing the methodology section, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. HM was responsible for writing the introduction,

conducting data analysis, writing the results, and actively participated in the review and editing process. HAN made substantial contributions to the literature review section and provided

valuable input during the review and editing process. EG also contributed to the literature review section and played a significant role in the review and editing process of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Asma Almusharraf. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL Based on Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud

Islamic University (IMSIU) institutional review board rules and regulations, the instruments used in this research were reviewed and approved. The IRB approval number (638328510668828125)

was granted. INFORMED CONSENT Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION TOTAL FOR ALL TESTS PRETEST ASSESSMENT POST AND GENERALIZATION TEST ASSESSMENT DELAYED TEST ASSESSMENT

YOUGLISH SURVEY (RESPONSES) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Almusharraf, A., Aljasser, A., Mahdi, H.S. _et al._ Exploring the effects of modality and variability on EFL learners’ pronunciation of English diphthongs: a

student perspective on HVPT implementation. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 11, 141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02632-2 Download citation * Received: 15 September 2023 * Accepted: 08

January 2024 * Published: 20 January 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02632-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative