Clinical predictors for perioperative anticipated and unanticipated difficult intubation: a matched case-control study

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT We aimed to determine the clinical predictors of perioperative anticipated and unanticipated difficult intubation using a matched case-control study. We recruited patients

undergoing surgery with endotracheal intubation from 2015 to 2020. Difficult intubation was defined as at least 3 attempts to perform intubation with conventional or video laryngoscopy

before surgery. Controls were randomly selected in a ratio of 3:1 matching on year of surgery, site of operation and age within 5 years. Clinical predictors were evaluated. A multivariate

conditional logistic regression analysis was performed and presented with adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We selected 168 cases and 504 controls out of 62,111

intubated patients. The predictors for anticipated difficult intubation were previous history of difficult airway (OR [95% CI]: 6.4 [1.3,32.5]) and abnormal facial appearance/syndrome (OR

[95% CI]: 6.1 [1.3,28.0]). The predictors of unanticipated difficult intubation were BMI < 15 kg/m2 (OR [95% CI]: 4.6 [1.5,14.4]), ASA physical status of 3 (OR [95% CI]: 3.6 [1.1,11.3]),

airway/neck/oral deformity (OR [95% CI]: 2.1 [1.03,4.3]) and tumors at intraoral, airway or thyroid (OR [95% CI]: 2.4 [1.1,4.9]). Undiagnosed airway/neck/oral deformity and tumors at

intraoral, airway or thyroid sites might be encountered with unanticipated difficult intubation, especially in patients who have a normal general appearance. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY

OTHERS IMPACT OF MULTIPLE INTUBATION ATTEMPTS ON ADVERSE TRACHEAL INTUBATION ASSOCIATED EVENTS IN NEONATES: A REPORT FROM THE NEAR4NEOS Article 18 August 2022 FACTORS THAT DETERMINE FIRST

INTUBATION ATTEMPT SUCCESS IN HIGH-RISK NEONATES Article Open access 30 September 2023 DOES VIDEOLARYNGOSCOPY IMPROVE TRACHEAL INTUBATION FIRST ATTEMPT SUCCESS IN THE NICUS? A REPORT FROM

THE NEAR4NEOS Article 03 August 2022 INTRODUCTION Difficult tracheal intubation is rare but can lead to high morbidity such as hypoxemia, tracheal injury, prolonged ventilator support and

life-threatening conditions1. Two studies in Thailand2,3 reported an incidence of difficult tracheal intubation between 2.2 and 6%. Most studies focused on high-risk difficult airway

patients such as those with obesity3,4, avoidance of neuromuscular blocking agents5, and previous history of tracheal intubation5. Cattano et al.6 reported that the airway assessments such

as high mallampati (MP) grade, low interincisor gap distance, and limitation of neck movement might not be highly related with operator endotracheal intubation difficulty scale score.

Intubation difficulty scale (IDS) also focused on airway assessment rather than clinical assessment related to patient-, surgery- and anesthesia-related factors. Also, IDS was used after

applying laryngoscopy, not for prediction before intubation7. A review of anticipated and unanticipated difficult airway management did not report risk factors8. Therefore, the aim of this

study is to determine the clinical predictors of anticipated and unanticipated difficult intubation in terms of patient-, surgery- and anesthesia-related factors in order to increase

awareness of unexpected difficult airway in perioperative patients. METHODS This retrospective, time-, operation- and age-matched, case-control study was conducted in December 2020 and was

approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand on 15 January 2021 (REC 63-560-8-1). We confirmed that all

methods were performed according to the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki9. The data were accessed on 16 January 2021 after the Ethics Committee’s approval. All data

were fully anonymized before being accessed by the investigators. All patient-, anesthesia-, and surgery-related information was retrieved from the anesthetic recording system and Hospital

Information System (HIS) of Songklanagarind Hospital. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine,

Prince of Songkla University. PARTICIPANTS The anesthesia database from HIS was used to identify all patients who required surgery with endotracheal tube intubation between January 1, 2015

and December 31, 2020. We excluded patients who had preoperative mechanical ventilation. Difficult airway cases were searched in the HIS using a quality assurance process and double

validated by the two of the authors (CK and WJ). Cases were recruited by the code of difficult intubation criteria, while controls were randomly selected from those who were not coded as

difficult intubation using a computer-generated program in a ratio of 1:3 such that one control had a previous history of difficult intubation or preoperative anticipated difficult airway

from anesthesia team while two others had no history of difficult intubation. Cases were also matched with the controls on the year of surgery (within 1 year), site of operation and age

within 5 years. STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES In our institution, the decision to perform general anesthesia with endotracheal tube intubation or awake intubation was made by the

anesthesiologist staff. In case of unexpected difficult intubation, a neuromuscular blocking agent such as rocuronium 0.5–0.9 mg/kg or cisatracurium 0.1–0.2 mg/kg was used intravenously (IV)

for intubation. Succinylcholine (1.5 mg/kg IV) is not routinely used in our institution, except for rapid sequence induction and intubation. Propofol 2–3 mg/kg IV is the main induction

agent used. Sevoflurane (1–2 minimum alveolar concentration), rather than desflurane (1–2 minimum alveolar concentration), is used for volatile anesthetic agents to minimize airway

complications. Since we are a university hospital, the first intubation personnel are usually a trainee such as anesthesia resident or anesthetist student supervised by anesthesiologist

staff. The anesthetists nurse recorded all details of the intubation procedure such as the experiences of intubation personnel, attempts, type of laryngoscopy, intubation time, success rate

and complications (if any) after endotracheal intubation. DEFINITION OF DIFFICULT INTUBATION Difficult intubation was defined as at least 3 attempts to perform an endotracheal tube

intubation with conventional or video laryngoscopy on the same patient by anesthesiologist personnel (anesthesia resident/nurse anesthetist/anesthesiologist staff) who had at least one year

of experience before commencing surgery. EXPLANATORY VARIABLES AND POTENTIAL RISK FACTORS Potential risk factors for difficult intubation were categorized into patient-, surgery-, and

anesthesia-related factors. Patient-related factors included sex, age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), previous history of difficult airway, underlying disease (congenital heart

disease, obstructive sleep apnea), potential abnormal airway problem such as airway/neck/oral deformity, airway and neck infection, tumors at intraoral, airway or thyroid, airway and neck

area, burn, and post-radiation. The only surgery-related factor was operation site which was used as a matching variable. Anesthesia-related factors included the American Society of

Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, intubation personnel, experience of intubation personnel, airway assessment such as MP score, thyromental distance, interincisor gap, limitation of

neck flexion and extension, upper lip bite test, abnormal facial appearance/ syndrome, and edentulous. DEFINITION OF EXPLANATORY VARIABLES Obstructive sleep apnea was defined as having

history of snoring diagnosed by history or polysomnography. Airway/neck/oral deformity was defined as having oropharyngeal or laryngeal or neck deformity such as subglottic/tracheal

stenosis, laryngeal papilloma, or scar contracture. Airway and neck infection was defined as having retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, supraglottitis, or croup. Tumors at the intraoral

area and airways as referred to tumors at the oropharynx, nasopharynx, larynx and tracheobronchus. Abnormal facial appearance/ syndrome was defined as having abnormal appearance from the

outside or a dysmorphic face. OUTCOMES AND COMPLICATIONS OF DIFFICULT INTUBATION The outcomes of intubation regarding technique of endotracheal tube intubation (general anesthesia, awake

intubation), type of endotracheal tube intubation (Macintosh/ Miller laryngoscopy, video laryngoscopy, fiberoptic bronchoscopy), intubation attempts, laryngoscopic view grade 1–4 classified

by Cormack and Lehane10,11, definite airway (endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy), extubation or remain intubated were also recorded. Laryngoscopic view grade 1–4 were defined as follows:

grade 1: the entire glottis was seen; grade 2: only the posterior commissure of the glottis was seen; grade 3; only the epiglottis was seen, and grade 4; any part of laryngeal structure was

not seen10,11. The major complications were cardiac arrest, hypoxemia, esophageal intubation, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and cricoarytenoid dislocation while tongue injury, buccal mucosal

injury, lip trauma, and dental injury were considered as minor complications. Hypoxemia was defined as SpO2 less than 92% by pulse oximeter. SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION We estimated the

prevalence of exposure (potential predictor) among the controls to be 15% to detect an odds ratio of at least 2.0 using a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%12 that resulted in a

required sample size of 157 cases and 471 controls. Therefore, 628 patients were required. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Descriptive results are presented as the mean with standard deviation, median

with interquartile range, or frequency with percentage. Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess bivariate associations between categorical variables and reintubation.

Continuous variables were evaluated using Student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney test for normally distributed and non-normally distributed data, respectively. The univariate analysis was

screened by the cross- tabulation between the difficult intubation and no difficult intubation groups and confirmed by univariate conditional logistic regression. Variables with a p-value

< 0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the initial multivariate conditional logistic regression model. The matching ID was used as a strata variable in the multivariate model.

Utilizing a backward selection procedure, the final regression model was determined by selecting all remaining significant variables. Variables having a p-value < 0.05 were deemed to be

statistically significant. A multivariate conditional logistic regression analysis was performed and presented with adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Missing data

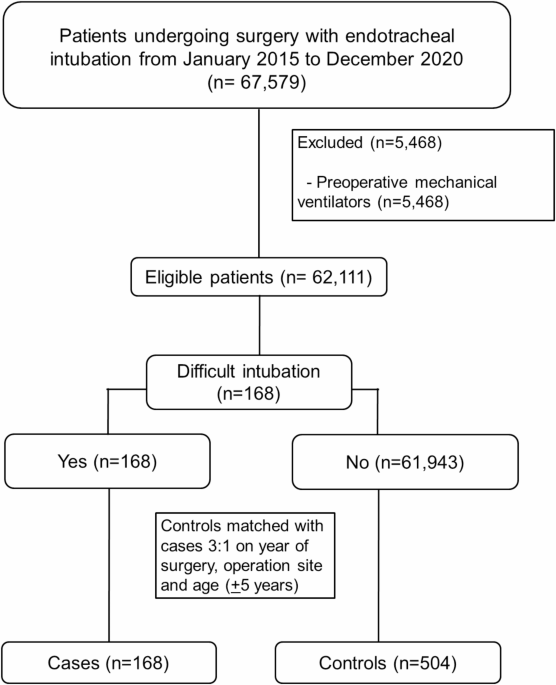

were reported and automatically excluded in the analysis process. The data were analyzed using R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team (2022). RESULTS A total of 67,579 patients had surgery with

endotracheal intubation during the study period. We excluded 5,468 patients who had preoperative mechanical ventilators before surgery. The incidence of difficult intubation was 0.27% (168

of 62,111 eligible patients) (Fig. 1). The control group matching on the same year and same site of operation and age within 5 years comprised 504 patients who had no difficult intubation.

Among those with difficult intubation the median number of attempts at intubation was 4. Patient related-factors associated with difficult intubation were lower BMI, previous history of

difficult airway, airway/neck/oral deformity, tumors at the intraoral area, airway or thyroid, history of head & neck radiation and laryngeal edema (Table 1). Associated surgery- and

anesthetic-specific factors and airway parameters were ASA physical status, limited neck flexion and extension, high grade upper lip bite test, and abnormal facial appearance/syndrome (Table

2). 50% of abnormal facial appearances were children with dysmorphic facial appearance or having syndrome, e.g. Down syndrome, Pierre Robin, Hurler syndrome, and Apert syndrome. OUTCOMES

AND COMPLICATIONS OF DIFFICULT INTUBATION The outcomes and complications of difficult intubation are shown in Table 3. An awake intubation compared to one using general anesthesia was

significantly associated with difficult intubation (10.7% vs. 4.2%). Use of video laryngoscopy and fiberoptic bronchoscopy were significantly associated with difficult intubation (74.3% and

9.0%) compared to the no difficult intubation group (12.3% and 3.0%, respectively). Definite airway via tracheostomy was significantly higher in the difficult intubation group (9.0 and 1.0%,

respectively). The major complications of difficult intubation group were cardiac arrest (2.4%), hypoxemia (7.1%) and esophageal intubation (6.5%) while buccal mucosal injury (2.4%) and lip

trauma (71%) were minor complications. There was a higher proportion of difficult intubation among patients who remained intubated postoperatively compared to those who did not (24.6% and

12.1%, respectively). All difficult airway cases received definite airway with 91% successful tracheal intubation and 9% tracheostomy. No patients died after experiencing a difficult

intubation. PREDICTORS OF ANTICIPATED AND UNANTICIPATED DIFFICULT INTUBATION Univariate conditional logistic regression analysis for intraoperative difficult intubation is shown in Table 4.

Eleven potential patient-related factors (sex, BMI, previous history of difficult airway, airway/neck/oral deformity, pharyngeal infection, post-thyroid procedures, tumors at intraoral,

airway or thyroid, burns at head, neck, face, history of head & neck radiation, laryngeal edema, and coagulopathy) and eight anesthesia-related factors (ASA physical status, MP score,

thyromental distance, interincisor gap, limit neck flexion and extension, upper lip bite test, abnormal facial appearance/syndrome, and overbite) that had p-value < 0.2 were included in

the initial conditional multivariate logistic regression model. Of these, six remained in the final model, namely: lower BMI (vs. BMI _≥_ 30 kg/m2), previous history of difficult airway, ASA

physical status 3 (vs. 1), airway/neck/oral deformity, tumors at intraoral, airway or thyroid, and abnormal facial appearance/syndrome. The clinical predictors of anticipated and

unanticipated difficult intubation are shown in Table 5. DISCUSSION Our incidence of difficult tracheal intubation between 2015 and 2020 was relatively low (0.27%) compared to previous

studies2,3,13,14. This might be due to the early use of video laryngoscopy, 100% coverage by anesthesiologist staff and availability of otolaryngologist staff for surgical airway. We found

that previous history of difficult airway and abnormal facial appearances were associated with a 6.3 and 6.1 times higher likelihood of difficult intubation than patients who neither had a

history of difficult airway nor abnormal facial appearances, respectively. Half of patients with abnormal facial appearances were children with Down syndrome, Pierre Robin syndrome, Hurler

syndrome, or Apert syndrome. Pierre Robin syndrome is usually associated with micrognathia while Apert syndrome is associated with midface hypoplasia, which leads to difficult airway

management15. Other studies also reported that other syndromes with dysmorphic facial appearance were associated with difficult tracheal intubation such as Treacher Collins syndrome and

Goldenhar syndrome16,17,18. Patients who had airway/neck/oral deformity had two-fold increased risk of difficult intubation than those who had no airway deformity. In case of airway

deformity diagnosed before anesthesia, the anesthesia personnel can make all the necessary preparations for an anticipated difficult airway. However, in situations where airway deformity

cannot be recognized, unanticipated difficult airway may be encountered. Nishimor et al.19 reported an undiagnosed case of oropharyngeal stenosis from an unknown history of previous upper

airway surgery, which developed an inability to perform tracheal intubation after anesthesia; consequently, the surgery was cancelled. Thus, in the anticipated situation, the anesthesia team

can promptly summon an expert in airway management, especially a pediatric anesthesiologist, prepare difficult airway equipment, and coordinate a plan of airway management. In case of an

undiagnosed or unanticipated situation, the emergency anesthesia team should be promptly called for any emergency or life-threatening conditions such as airway collapse and failed

intubation. The significant risk factors for unanticipated difficult intubation were lower BMI, high ASA physical status, and tumors at the intraoral site, airway or thyroid. Lower BMI

patients was associated with a higher chance of having difficult intubation (4.6-times for BMI < 15 kg/m2 and 2.7-times for BMI 15–29 kg/m2). While obesity was considered as a high risk

of difficult intubation in this study, previous studies showed marginal results3,4,20. Mantaga et al.3 reported and IDS score of 2.2 in obesity (BMI at least 30 kg/ m2) while IDS > 5 was

considered as difficult intubation. Siriussawakul et al.4 reported an incidence of difficult intubation in patients with obesity (BMI at least 30 kg/ m2) of only 3.2%. Shailaja et al.20 also

reported that patients with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2 were slightly more difficult to intubate than normal patients (BMI < 25 kg/m2) (11% vs. 7%). In our study, we found that all

patients who had a previous history of difficult intubation were non-obese (BMI < 30 kg/ m2). Among the patients with a BMI < 15 kg/m2, 77% (41/53) were children aged less than 7

years. Chen et al.21 reported a pediatric cerebral palsy case with complicatedly difficult airway from laryngomalacia who also had a low BMI from difficult feeding. Moreover, the poor

nutrition and difficult airway could be associated from some condition like bronchopulmonary dysplasia that children developed severe tracheomalacia which can lead to difficult airway and

esophageal atresia leading to feeding difficulty22. ASA physical status 3 increased the odds of difficult intubation by a factor of 3.6-times compared to ASA physical status 1. In case of

suspected difficult airway, especially in children or adults who had airway abnormality, ASA physical status 3 was classified by anesthesia personnel in order to prepare an expert in airway

management and difficult airway equipment in advance. Oria et al.23 reported that ASA physical status 2 and 3 (with systemic disease) increased the risk of difficult intubation compared to

ASA physical status 1 (no systemic disease). Ki et al.24 also reported ASA physical status 4 patient who came for neurosurgery developed unanticipated difficult intubation from

laryngotracheal stenosis due to history of prolonged tracheal intubation. Therefore, patients with a high ASA physical status are more likely to have difficult airway than healthier

patients. Patients who had tumors at the intraoral site, airway or thyroid had an increased risk of difficult intubation by a factor of 2.4-times compared to patients who had no airway

tumors. Patients with intraoral tumors or thyroid masses that were not obviously detected from the airway assessment could experience unanticipated difficult airway. Li et al.25 reported

that tumor size was significantly associated with successful intubation OR (95% CI): 0.43(0.22–0.82). Nonetheless, the mild to moderate size of airway tumor might not be recognized at the

preoperative period among asymptomatic patients or patients who come for other types of surgery. Sagün et al.26 also reported that endocrine disease such as thyroid mass and the presence of

an intraoral cavity mass should be considered as a predictor of difficult intubation, a finding supported by our study. Therefore, unrecognized airway deformity or intraoral or airway tumors

at the preoperative period could eventually result in unanticipated difficult airway, especially in patients who seem to have a normal facial appearance. The application of the study is as

follows. The hospital policy following the Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults27 was adapted in 2019 throughout the

Advanced Hospital Accreditation process. Therefore, the continuous quality improvement required design-action-learning-improvement to ensure the sustainability of quality improvement28,29.

Our clinical predictors of anticipated and unanticipated difficult intubation have been included into the new version of the clinical practice guideline (CPG) to improve the hospital’s

management of difficult airways. Moreover, the CPG difficult airway management in our setting is also complied with 2022 ASA practices guideline for management of difficult airways30. The

strengths of the study are that we used a pool of over 60,000 patients to randomly select controls with matching to cases on the same year, site of operation and age. This reduced the

selection bias in terms of the same equipment and anesthetic agents used and the same anesthesia personnel during the same time period. Second, the multivariate conditional logistic

regression model was used to adjust for potential confounding variables. Third, we used an adequate sample size to examine the clinical predictors of difficult intubation with no missing

data in the final model. Although we attempted to minimize selection bias, some information bias could have occurred. First, airway assessment parameters contained 10–15% missing data, which

would have diluted the association with difficult intubation, but were removed from the final analysis. 3% of laryngoscopic view grade was unknown, but we considered this had low impact to

the validity of the data since the high grade of laryngoscopic view was significantly related with difficult intubation cases. Second, according to the definition of difficult intubation in

our study, the incidence of difficult intubation might be overestimated since 20–30% of the first intubation attempts were performed by first-year anesthesia residents or anesthetist

students who had experience < 1 year. However, when the first attempts failed, the anesthesiologist staff took over every case with conventional or video laryngoscopy. Third, the actual

time of airway management during airway difficulty was not included in the analysis since it is not routinely recorded. Fourth, three matching criteria used in our study might diminish the

statistical power of subsequent logistic regression and mask the potential predictors compared to no matching study31. However, age and type of surgery (airway surgery) which were potential

unmodifiable predictors, were used for matching to enhance potential unknown or other modifiable predictors in the final model. Finally, the generalizability of our results to other

hospitals in different settings might be limited since the subjects were recruited from a single university hospital. CONCLUSIONS The anticipated risk factors of difficult intubation were

previous history of difficult airway and abnormal facial appearance/syndrome while unanticipated risk factors were body mass index < 30 kg/m2, ASA physical status of 3, and the presence

of intraoral/thyroid tumors. Clinical factors that an anesthesiologist needs to be concerned with are undiagnosed airway/neck/oral deformity, and intraoral/thyroid tumors, especially in

patients who have a normal general appearance. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES * Chanchayanon, T. & Suraseranivongse, S. Chau-in, W. The Thai anesthesia incidents study (THAI study) of difficult intubation: a qualitative analysis. _J. Med. Assoc. Thai_

88(Suppl 7), S62–68 (2005). PubMed Google Scholar * Narasethkamol, A., Charuluxananan, S., Kyokong, O., Premsamran, P. & Kundej, S. Study of model of anesthesia related adverse event

by incident report at King Chulalongkorn memorial hospital. _J. Med. Assoc. Thai_ 94, 78–88 (2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Mantaga, S., Mitmak, P., Samankatiwat, S. & Siriussawakul,

A. The evaluation of difficult intubation among obese patients by using the intubation difficulty scale (IDS) at Ratchaburi hospital: a descriptive study. _Thai J. Anesthesiol._ 45, 7–14

(2019). Google Scholar * Siriussawakul, A. et al. Predictive performance of a multivariable difficult intubation model for obese patients. _PLoS One_. 13, e0203142 (2018). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lundstrøm, L. H. Detection of risk factors for difficult tracheal intubation. _Dan. Med. J._ 59, B4431 (2012). PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Cattano, D.

et al. Risk factors assessment of the difficult airway: an Italian survey of 1956 patients. _Anesth. Analg_. 99, 1774–1779 (2004). Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Nasa, V. K.

& Kamath, S. S. Risk factors assessment of the difficult intubation using intubation difficulty scale (IDS). _J. Clin. Diagn. Res._ 8, GC01–03 (2014). Google Scholar * Xu, Z., Ma, W.,

Hester, D. L. & Jiang, Y. Anticipated and unanticipated difficult airway management. _Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol._ 31, 96–103 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * World Medical

Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. _JAMA_ 310, 2191–2194 (2013). Article MATH Google Scholar

* Nasir, K. K., Shahani, A. S. & Maqbool, M. S. Correlative value of airway assessment by Mallampati classification and Cormack and Lehane grading. _Rawal Med. J._ 36, 2–6 (2011). MATH

Google Scholar * Yemam, D., Melese, E. & Ashebir, Z. Comparison of modified Mallampati classification with Cormack and Lehane grading in predicting difficult laryngoscopy among

elective surgical patients who took general anesthesia in Werabie comprehensive specialized hospital—cross sectional study. Ethiopia, 2021. _Ann. Med. Surg (Lond.)_ 79, 103912 (2022). PubMed

Google Scholar * Fahim, N. K., Negida, A. & Fahim, A. K. Sample size calculation guide—part 3: how to calculate the sample size for an independent Case-control study. _Adv. J. Emerg.

Med._ 3, e20 (2019). PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Levitan, R. M., Heitz, J. W., Sweeney, M. & Cooper, R. M. The complexities of tracheal intubation with direct

laryngoscopy and alternative intubation devices. _Ann. Emerg. Med._ 57, 240–247 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jung, H. A comprehensive review of difficult airway management

strategies for patient safety. _Anesth. Pain Med._ 18, 331–339 (2023). Article MATH Google Scholar * Ngwenya, M. Syndromic paediatric airway. _South. Afr. J. Anaesth. Analg._ 28(5 Suppl

1), S162–169 (2022). Google Scholar * Cladis, F. et al. Pierre robin sequence: a perioperative review. _Anesth. Analg._ 119, 400–412 (2014). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Mohan,

S., Del Rosario, T. J., Pruett, B. E. & Heard, J. A. Anesthetic management of treacher Collins syndrome in an outpatient surgical center. _Am. J. Case Rep._ 22, e931974 (2021). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Oofuvong, M., Valois, T. & Withington, D. E. Laryngeal mask airway and difficult airway management in adolescent: a case report. _Ped Anesth._

18, 1228–1229 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Nishimori, M., Matsumoto, M., Nakagawa, H. & Ichiishi, N. Unanticipated difficult airway due to undiagnosed oropharyngeal stenosis: a

case report. _JA Clin. Rep._ 2, 10 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Shailaja, S., Nichelle, S. M., Shetty, A. K. & Hegde, B. R. Comparing ease of intubation in obese and lean

patients using intubation difficulty scale. _Anesth. Essays Res._ 8, 168–174 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Chen, J. X., Shi, X. L., Liang, C. S., Ma,

X. G. & Xu, L. Anesthesia management in a pediatric patient with complicatedly difficult airway: a case report. _World J. Clin. Cases_ 11, 2482–2488 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed

Central MATH Google Scholar * Gunatilaka, C. C. et al. Increased work of breathing due to tracheomalacia in neonates. _Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc._ 17, 1247–1256 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed

Central MATH Google Scholar * Oria, M. S., Halimi, S. A., Negin, F. & Asady, A. Predisposing factors of difficult tracheal intubation among adult patients in Aliabad teaching

hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan—a prospective observational study. _Int. J. Gen. Med._ 15, 1161–1169 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ki, S., Cho, S. B., Park, S.

& Lee, J. Management of unanticipated difficult airway in a patient with well-visualized vocal cords using video laryngoscopy—a case report. _Anesth. Pain Med. (Seoul)_. 18, 204–209

(2023). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Li, W. X. et al. Risk factors for difficult mask ventilation and difficult intubation among patients undergoing pharyngeal and laryngeal

surgery. _Heliyon_ 9, e14408 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sagün, A., Ozdemir, L. & Melikogullari, S. B. The assessment of risk factors associated with

difficult intubation as endocrine, musculoskeletal diseases and intraoral cavity mass: a nested case control study. _Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg_ 28, 1270–1276 (2022). PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Mendonca, C. et al. Difficult airway society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult airway society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated

difficult intubation in adults. _Br. J. Anaesth._ 115, 827–848 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Valentine, E. A. & Falk, S. A. Quality improvement in

Anesthesiology—Leveraging data and analytics to optimize outcomes. _Anesthesiol. Clin._ 36, 31–44 (2018). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * O’Donnell, B. & Gupta, V. Continuous

quality, I. (StatPearls Publishing, 2024). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559239/. * Apfelbaum, J. L. et al. 2022 American society of anesthesiologists practice guidelines for

management of the difficult airway. _Anesthesiology_ 136, 31–81 (2022). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Kheterpal, S. et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask

ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: a report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. _Anesthesiology_ 119, 1360–1369 (2013). Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Assistant Professor Edward McNeil for editing the manuscript. FUNDING This work was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of

Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla, Thailand. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, 15

Kanjanavanich Road, Hat Yai, Songkhla, 90110, Thailand Pannawit Benjawaleemas, Maliwan Oofuvong, Chanatthee Kitsiripant, Wilasinee Jitpakdee, Nussara Dilokrattanaphichit, Wipharat

Juthasantikul, Pannipa Phakam & Qistina Yunuswangsa Authors * Pannawit Benjawaleemas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maliwan

Oofuvong View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chanatthee Kitsiripant View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Wilasinee Jitpakdee View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nussara Dilokrattanaphichit View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wipharat Juthasantikul View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pannipa Phakam View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Qistina Yunuswangsa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS All those listed as authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. Each listed author participated in the work and can defend its content. P.B. participated in its

design and revised the draft manuscript. M.O. coordinated the study, participated in the study design, undertook the statistical analysis and wrote the draft manuscript. C.K., W.J., N.D.,

W.J., and P.P. participated in its design and collected the data. Q.Y. coordinated the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Maliwan Oofuvong. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE The study was approved by

the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand, Chairperson Assoc. Prof. Boonsin Tangtrakulwanich, REC 63-560-8-1 on January

15, 2021. The consent to participate was not applicable. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction

in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the

licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and

your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this

licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Benjawaleemas, P., Oofuvong, M., Kitsiripant, C. _et al._

Clinical predictors for perioperative anticipated and unanticipated difficult intubation: a matched case-control study. _Sci Rep_ 15, 9078 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93609-x

Download citation * Received: 12 June 2024 * Accepted: 07 March 2025 * Published: 17 March 2025 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93609-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Anticipated difficult intubation * Unanticipated difficult intubation * Clinical predictors * Perioperative period