Seroprevalence and associated risk factors for bovine leptospirosis in egypt

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Leptospirosis is caused by pathogenic bacteria of the genus _Leptospira_ and is one of causative agents of reproductive problems leading to negative economic impact on bovine

worldwide. The goal of this study was to investigate the seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. in cattle in some governorates of Egypt's Nile Delta and assess the risk factors for

infection. A total of 410 serum samples were collected from cattle and examined using microscopic agglutination test. The overall seroprevalence was 10.2% and the most prevalent serovars

were Icterohaemorrhagiae, Pomona and Canicola. In addition, the potential risk factors were associated _Leptospira_ spp. infection were age, herd size, history of abortion, presence of dogs

and rodent control. Thus, leptospirosis is common in dairy cattle in the Nile Delta and the presence of rodents in feed and dog-accessible pastures increases the risk of _Leptospira_ spp.

infection among animals. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE ROLE OF SMALL RUMINANTS IN THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LEPTOSPIROSIS Article Open access 09 February 2022 _NEOSPORA CANINUM_

INFECTION IN DAIRY CATTLE IN EGYPT: A SEROSURVEY AND ASSOCIATED RISK FACTORS Article Open access 19 September 2023 SEROSURVEY AND ASSOCIATED RISK FACTORS FOR _NEOSPORA_ _CANINUM_ INFECTION

IN EGYPTIAN WATER BUFFALOES (_BUBALUS_ _BUBALIS_) Article Open access 21 December 2023 INTRODUCTION Leptospirosis is a global zoonotic threat that poses a global public health problem due to

its high mortality and morbidity rates1,2. The disease is caused by pathogenic bacterium of genus of _Leptospira_, which occurs primarily in tropical and subtropical countries where humid

climates and high temperatures favor bacterial growth3,4. This pathogen spreads mostly by direct or indirect exposure to urine of the principal reservoirs (rodents) and other animals.

Moreover, the bacterium persist in renal tissue of infected animals for variable periods and shedding in urine causing contamination to environment5,6. In cattle, infection can occur

directly through contaminated urine, post-abortion secretions, infected placenta, or sexual contact. However, indirect transmission plays a significant role in infection dissemination7,8.

Bovine leptospirosis is characterized mostly by reproductive losses such as abortions and stillbirths, as well as poor weight growth, mastitis, and reduction in milk yield. Nevertheless,

laboratory testing, primarily serological techniques, are used to support the diagnosis9,10. Human contract _Leptospira_ by coming into contact with infected urine or by visiting a

urine-contaminated environment11. Mucosal and conjunctival tissues as well as scratches and cuts are common entry points12. Human infections can cause severe, potentially fatal illnesses,

but in most cases remain asymptomatic or cause mild ailments. This disease causes non-specific signs and symptoms, including fever, headaches, dry coughs, abdominal discomfort, myalgia, and

nausea13. The epidemiology of leptospirosis and the incidence of the disease in the cattle herds have both been found to be significantly influenced by the presence of dogs on rural farms14.

Cattle positive serology has shown that rodents that have direct contact with cattle feeding are another significant risk factor15. For a definitive diagnosis of leptospirosis, laboratory

testing is required. Dark-field microscopy can be used to show the organism in the blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid16,17. The ELISA is used as a first screening test and is a crucial

piece of clinical immunology equipment. For the diagnosis of leptospirosis, additional tests are employed, such as the microscopic agglutination test, fluorescent antibody test, indirect

hemagglutination test, radial immunoassay, complement fixation test, and PCR18,19,20. The most often used laboratory technique for _Leptospira_ diagnosis is ELISA, which is also commercially

accessible. PCR is less frequently employed. ELISA can identify antibodies from the second weeks of infection forward and has higher sensitivity and specificity than the microscopic

agglutination test21. The global prevalence of animal leptospirosis with wide ranges from 2 to 46% according to animal species22,23, this variation might be climatic changes and diagnostic

techniques. In Egypt, the previous researches focused on leptospirosis in people exposed to animals. The ELISA test used to identify Leptospiral antibodies in people with unexplained acute

febrile sickness and hepatitis24. However, little information is known on the prevalence of leptospirosis in cattle across Egypt's key cattle-producing provinces, notably the Nile Delta

province, which includes Dakahlia Governorate25. This study aimed to identify seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. infection and to assess risk factors associated with _Leptospira_ infection

in dairy cattle in northern Egypt. MATERIALS AND METHODS ETHICAL STATEMENT Benha University's ethics committee for animal research approved the study's methodology and techniques.

All cattle owners provided informed consent to participate in the study. The Faculty of Veterinary Medicine's ethics committee guaranteed that all operations followed all applicable

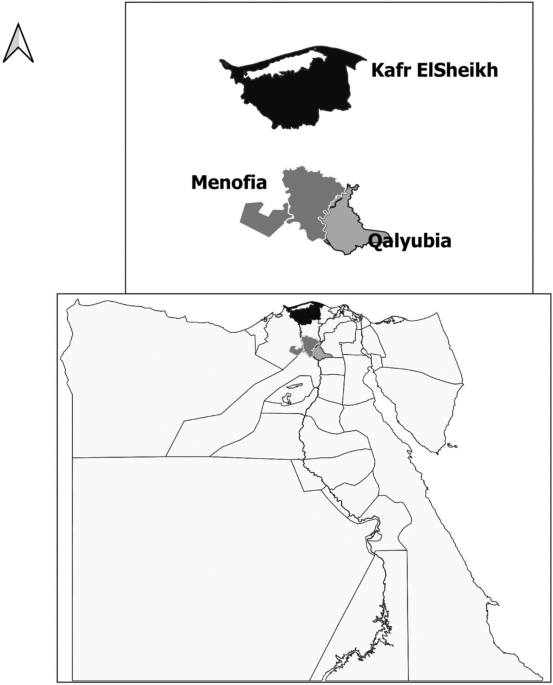

rules. The ARRIVE criteria were followed throughout the study process. STUDY SITE This study was performed during the period of March 2021 to February 2022 and cover three governorates (Kafr

ElSheikh, Menofia and Qalyubia) situated at Nile Delta of Egypt, Fig. 1. The selected governorates are located at latitudes 31° 06′ 42″ N, 30.52° N, and 30.867° N, respectively, and at

longitudes 30° 56′ 45″ E, 30.99° E, and 31.028° E. A hot desert climate dominates the Nile Delta in general, but in its northernmost part, which is also the wettest region in Egypt, it has

relatively moderate temperatures with a high of 31 °C in the summer, as is the case with all of the northern coast of Egypt. SAMPLE DESIGN AND SAMPLING The sample size were determined using

the following formula according26 using the procedure for simple random sampling: $${\text{N}} = Z^{{{2}*}} P\left( {{1} - P} \right)/d^{{2}}$$ where n is the sample size, _P_ is the

predicted prevalence 50%, _Z_ = 1.96 with 95% confidence level, and _d_ is the absolute error 5%. The calculated number of samples was 384 and increased to 410 to increase the precision. In

order to obtain serum, cattle blood samples were collected using vacuum tubes without anticoagulant through punctured the jugular vein and centrifuged at 3000 xg for ten minutes. the serum

was stored at − 20 °C in 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes till serological examination was completed. DATA COLLECTION Cattle owners provided the database with their individual information to identify

potential risk factors for leptospirosis seropositivity. At the time of blood sampling, each participant filled out a questionnaire. A number of variables were selected: (1) location (Kafr

ElSheikh, Menofia and Qalyubia), (2) age (2, 2–3, and > 3 years), (3) sex (male and female), (4) herd size (50, 50–75, and > 75), (5) gestation status (pregnant and non-pregnant), (6)

history of abortion (yes or no), (7) presence of dogs (yes or no), and 8) rodent control (yes or no). The samples were collected randomly from individual farmer, two medium herds and one

large herd. SEROLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS In accordance with the recommendations of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the serological diagnosis was carried out using a microscope

equipped with a dark field condenser to conduct the microscopic agglutination test (MAT) as described by27. The panel of antigens utilized in this investigation contained seven common

strains, taking into account the most common serovars of _Leptospira interrogans_ in the country: Canicola, Hardjo, Pomona, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Grippotyphosa, Bratislava, and Copenhageni. A

dilution of 1:50 was used for the initial testing of sera samples, and those with an agglutination level equal to or greater than 50% were further diluted. The final titration was

calculated as the dilution at which 50% agglutination was detected. A titration of 1:50 indicated that the animals had been exposed to the causative agent. Titrations of 1:100 were regarded

as positive for _Leptospira_ infection. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS The data from the questionnaires were analysed to identify potential risk factors for leptospirosis seropositivity. The analysis

was done in two stages: univariate and multivariate. In the univariate analysis, each independent variable was crossed with the dependent variable (seropositivity), and those with a

chi-square test _P_-value < 0.20 were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis28,29,30,31,32,33. A correlation analysis was used to confirm collinearity between independent

variables; for those variables with substantial collinearity (correlation coefficient > 0.9). The statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software ver. 24 (IBM < USA). RESULTS In

total, out of 410 animals examined, 42 tested seropositive, indicating a seroprevalence of 10.2% (95% CI 7.66–13.55). The analysis of the identified sera revealed that serovar

Icterohaemorrhagiae was the most prevalent at 2.9% (95% CI 1.68–5.05), while Copenhageni exhibited the lowest occurrence with 0.24% (95% CI 0.04–1.36), Table 1. The univariate analysis for

the variables associated to seropositivity for any _Leptospira_ spp. serovar in cattle were presented in Table 2. The seroprevalence revealed non-significant (_P_ > 0.05) association

between locality, sex and gestation status and _Leptospira_ seropositivity. The seroprevalence rose with age and was substantially (_P_ < 0.05) higher in cattle over 5 years old (15.8%),

particularly in those raised in large herd sizes (37.1%). Furthermore, _Leptospira_ seroprevalence in cattle increased significantly (_P_ < 0.05) in animals with a history of miscarriage

(16.4%), in animals living with dogs (18.7%), and in homes without rodent management (14.2%), Table 2. The variables with _P_ < 0.2 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate

logistic regression model. The variables were identified as risk factors in multivariate model for _Leptospira_ seropositivity were age more than five years (OR 7.24, _P_ = 0.027), large

herd size more than 75 (OR 30.53, _P_ < 0.0001), animal with history of abortion (OR 1.49, _P_ = 0.036), presence of dogs (OR 6.32, _P_ < 0.0001) and absence of rodents control (OR

2.03, _P_ = 0.010), Table 3. DISCUSSION Leptospirosis is a global zoonotic threat and information on the disease's epidemiology and the variables that contribute to its incidence is

very important to improve the control level of leptospirosis34. In particular, few studies to our knowledge have been considered the epidemiological situation of leptospirosis in cattle in

Dakhalia governorates but no data about its prevalence in other governorates of Nile Delta. Therefore, one of the major aim of this study is determination the seroprevalence of _Leptospira_

spp. in cattle in three Egyptian governorates and assess its associated potential risk variables. In this study, the seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. in cattle raising the three studied

governorates in Nile Delta (Kafr ElSheikh, Menofia and Qalyubia) was 10.2% (95% CI 7.66–13.55). In another Nile Delta governorate, cattle seroprevalence was estimated to be 39.33%25. As a

result, the findings emphasise the significance of this disease in the country and the necessity to develop effective control measures to lower its incidence. However, the _Leptospira_ spp.

seroprevalence is higher in some countries such as 81.7% in Northeastern Malaysia35, 89.9% in Poland36, 88.2% in Mexico37, 81% in Chile38, and 87% in India39. Alternatively, lower

prevalences have been reported in some countries, it was 3% in North Eastern India40, 3.2% in Poland41, 13% in Tanzania42, 20.3% in Sri Lanka43, 31.3% in Brazil44, and 24.48% in southwestern

Ethiopia45. Several factors may contribute to this variation, including geography, husbandry practices, management, sampling and diagnostic method, natural immunity, and disease

resistance9,14,30,32,33,45,46,47. In addition, high densities of infected cows with _Leptospira_ spp. might lead to environmental contamination and disease spreading since they could serve

as reservoirs and spread infection to other animals residing in the same habitat48. Interestingly, the most prevalent serovars among examined cattle in the present study were

Icterohaemorrhagiae (2.9%), Pomona (2.2%) and Canicola (1.9%). These findings are in accordance with previous findings reported by49 and50, they found the most common serovars in cattle

Pomona and Icterohaemorrhagiae. Moreover, Icterohaemorrhagiae and Pomona serogroups are associated to animal interaction with various animal species that serve as reservoirs for the

diseases51. In the present study, the seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. did not varied between studied governorates because all of them situated in the Nile Delta and have the same

climatic features and topographic characters52. Moreover, Marzok, et al.52 found that the most prevalent serovars in Egypt was Icterohaemorrhagiae, Canicola and Pomona. Similar to previous

findings of dos Santos, et al.44, but in contrast with findings of Parvez, et al.53, the seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. increased significantly with age. In addition, in an Indian

investigation, Sudharma and Veena54 observed that the seroprevalence was not correlated with animal age. This might be attributable to the fact that exposure to _Leptospira_ becomes more

common as old cattle, and that seropositivity can remain for a very long period1,25. The present findings revealed that the females were more seropositivity for _Leptospira_ spp. than males,

this consistent with previous findings of El-Deeb, et al.25 and Ijaz, et al.55. However, many previous studies have shown that males are more likely to contract leptospirosis than females

without a significant variation56,57. There is no clear explanation for these findings and reported differences in relation to sex57. The result of present study might be contributed to most

of the samples examined were collected from female cows which give its potential influence. _Leptospira_ spp. seroprevalence significantly increased in large herd size in accordance with

prior findings of Benseghir, et al.58. This finding may be explained by inadequate sanitation facilities, difficulty in monitoring hygienic practices on large herds compared to small herds

and Leptospiral infection spread rapidly in overcrowded farms which have poor management and sanitation application4,35,44,55. In the current study, the prevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. was

higher in cattle suffered from history of abortion or second semester of pregnancy. The findings confirm previous reports that _Leptospira_ spp. present chronically in bovines and can lead

to sexual dysfunction, low fertility, and abortion59,60. The presence of dogs increased the prevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. in cattle, which come in agreement with previous findings of

Fávero, et al.49. Moreover, _Leptospira_ spp. were more prevalent in cattle raising farm which have poor management and rodent control. Similar findings were concluded by Motto, et al.42.

Rodents are mostly recognized epidemiologically for spreading various pathogenic _Leptospira_ and contaminating pasture61, and as a result, animals may contract leptospirosis during

grazing62. CONCLUSION The results of present study confirmed that _Leptospira_ spp. present among cattle in Nile Delta of Egypt, contributed as cause of abortion in pregnant animals. The

multivariate logistic regression model identified age, herd size, history of abortion and control of rodents as potential risk factors for _Leptospira_ spp. infection. The identification of

species and biovars, the understanding of transmission cycles, and the implementation of preventative and control measures are critical, particularly for dairy cows, as well as identifying

alternatives to management practices that could spread disease to people or animals. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published

article. REFERENCES * Karpagam, K. B. & Ganesh, B. Leptospirosis: A neglected tropical zoonotic infection of public health importance-an updated review. _Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.

Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol._ 39, 835–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03797-4 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pham, H. T. & Tran, M. H. One health: An

effective and ethical approach to leptospirosis control in Australia. _Trop. Med. Infect. Dis._ https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7110389 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Alemayehu, G. _et al._ Causes and flock level risk factors of sheep and goat abortion in three agroecology zones in Ethiopia. _Front. Vet. Sci._ 8, 615310.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.615310 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Langston, C. E. & Heuter, K. J. Leptospirosis: A re-emerging zoonotic disease. _Vet.

Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract._ 33, 791–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-5616(03)00026-3 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Muñoz-Zanzi, C., Mason, M. R., Encina, C., Astroza,

A. & Romero, A. _Leptospira_ contamination in household and environmental water in rural communities in southern Chile. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 11, 6666–6680.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110706666 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Belmaker, I. _et al._ Risk of transmission of leptospirosis from infected cattle to dairy

workers in southern Israel. _Israel Med. Assoc. J. IMAJ_ 6, 24–27 (2004). PubMed Google Scholar * Le Turnier, P. & Epelboin, L. Update on leptospirosis. _La Revue de medecine interne_

40, 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2018.12.003 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sohm, C. _et al._ A systematic review on leptospirosis in cattle: A European perspective.

_One Health_ 17, 100608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100608 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dogonyaro, B. B. _et al._ Seroepidemiology of _Leptospira_

infection in slaughtered cattle in Gauteng province, South Africa. _Trop. Anim. Health Prod._ 52, 3789–3798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02417-0 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Gelalcha, B. D., Robi, D. T. & Deressa, F. B. A participatory epidemiological investigation of causes of cattle abortion in Jimma zone, Ethiopia. _Heliyon_ 7,

e07833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07833 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Martins, G., Penna, B. & Lilenbaum, W. The dog in the transmission of

human leptospirosis under tropical conditions: Victim or villain?. _Epidemiol. Infect._ 140, 207–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268811000276 (2012) (AUTHOR REPLY 208–209). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Lau, C. L. _et al._ Human leptospirosis infection in Fiji: An eco-epidemiological approach to identifying risk factors and environmental drivers for transmission.

_PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis._ 10, e0004405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004405 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bharti, A. R. _et al._ Leptospirosis: A zoonotic

disease of global importance. _Lancet. Infect. Dis_ 3, 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chiebao, D. P. _et al._ Variables

associated with infections of cattle by Brucella abortus., _Leptospira_ spp. and _Neospora_ spp. in Amazon Region in Brazil. _Transboundary Emerg. Dis._ 62, e30-36.

https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12201 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Talebkhan Garoussi, M., Mehravaran, M., Abdollahpour, G. & Khoshnegah, J. Seroprevalence of leptospiral

infection in feline population in urban and dairy cattle herds in Mashhad, Iran. _Vet. Res. Forum : Int. Q. J._ 6, 301–304 (2015). Google Scholar * Musso, D. & La Scola, B. Laboratory

diagnosis of leptospirosis: A challenge. _J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect._ 46, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.001 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Budihal, S.

V. & Perwez, K. Leptospirosis diagnosis: Competancy of various laboratory tests. _J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR_ 8, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2014/6593.3950 (2014). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Hernández-Rodríguez, P., Díaz, C. A., Dalmau, E. A. & Quintero, G. M. A comparison between polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and traditional techniques for the

diagnosis of leptospirosis in bovines. _J. Microbiol. Methods_ 84, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.021 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Otaka, D. Y. _et al._

Serology and PCR for bovine leptospirosis: Herd and individual approaches. _Vet. Rec._ 170, 338. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.100490 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schafbauer,

T. _et al._ Seroprevalence of _Leptospira_ spp. infection in cattle from central and Northern Madagascar. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16112014

(2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ahmad, S. N., Shah, S. & Ahmad, F. M. Laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis. _J. Postgrad. Med._ 51, 195–200 (2005). CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Leal-Castellanos, C. B., García-Suárez, R., González-Figueroa, E., Fuentes-Allen, J. L. & Escobedo-de la Peñal, J. Risk factors and the prevalence of

leptospirosis infection in a rural community of Chiapas, Mexico. _Epidemiol. Infect._ 131, 1149–1156. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268803001201 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * de Faria, M. T. _et al._ Carriage of _Leptospira_ interrogans among domestic rats from an urban setting highly endemic for leptospirosis in Brazil. _Acta Trop._ 108, 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.07.005 (2008). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Samir, A., Soliman, R., El-Hariri, M., Abdel-Moein, K. & Hatem, M. E.

Leptospirosis in animals and human contacts in Egypt: Broad range surveillance. _Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical_ 48, 272–277.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0102-2015 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * El-Deeb, W. _et al._ Assessment of the immune response of clinically infected calves to Cryptosporidium

parvum infection. _Agriculture_ 12, 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12081151 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * Thrusfield, M. _Veterinary Epidemiology_ (Wiley, 2018). Book

Google Scholar * OIE. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, Leptospirosis. _World Organization for Animal Health, Paris_ (2014). * Selim, A., Abdelrahman, A.,

Thiéry, R. & Sidi-Boumedine, K. Molecular typing of Coxiella burnetii from sheep in Egypt. _Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis._ 67, 101353.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2019.101353 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Selim, A., Almohammed, H., Abdelhady, A., Alouffi, A. & Alshammari, F. A. Molecular detection and

risk factors for _Anaplasma platys_ infection in dogs from Egypt. _Parasites & vectors_ 14, 429. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04943-8 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Selim,

A., Attia, K. A., Alsubki, R. A., Kimiko, I. & Sayed-Ahmed, M. Z. Cross-sectional survey on _Mycobacterium avium_ Subsp. _paratuberculosis_ in dromedary camels: Seroprevalence and risk

factors. _Acta Tropica_ 226, 106261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.106261 (2022). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Selim, A., Khater, H. & Almohammed, H. I. A recent

update about seroprevalence of ovine neosporosis in Northern Egypt and its associated risk factors. _Sci. Rep._ 11, 14043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93596-9 (2021). Article ADS

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Selim, A., Manaa, E. & Khater, H. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of lumpy skin disease in Egypt. _Comp. Immunol.

Microbiol. Infect. Dis._ 79, 101699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2021.101699 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Selim, A., Manaa, E. A., Alanazi, A. D. & Alyousif, M. S.

Seroprevalence, risk factors and molecular identification of bovine leukemia virus in Egyptian cattle. _Animals_ 11, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020319 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Harran, E. _et al._ Molecular and Serological Identification of Pathogenic <i>Leptospira</i> in Local and Imported Cattle from Lebanon. _Transboundary

Emerg. Dis._ 2023, 3784416. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3784416 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Daud, A. _et al._ Leptospirosis seropositivity and its serovars among cattle in

Northeastern Malaysia. _Vet. World_ 11, 840–844. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2018.840-844 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Czopowicz, M. _et al._ Leptospiral

antibodies in the breeding goat population of Poland. _Vet. Rec._ 169, 230. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.d4403 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Joel, N. E., Maribel, M. M.,

Beatriz, R. S. & Oscar, V. C. Leptospirosis Prevalence in a Population of Yucatan, Mexico. _J. Pathogens_ 2011, 408604. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/408604 (2011). Article Google

Scholar * Salgado, M., Otto, B., Sandoval, E., Reinhardt, G. & Boqvist, S. A cross sectional observational study to estimate herd level risk factors for _Leptospira_ spp. serovars in

small holder dairy cattle farms in southern Chile. _BMC Vet. Res._ 10, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-126 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Natarajaseenivasan, K. _et al._ Seroprevalence of _Leptospira borgpetersenii_ serovar javanica infection among dairy cattle, rats and humans in the Cauvery river valley of southern India.

_Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health_ 42, 679–686 (2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Leahy, E. _et al._ _Leptospira interrogans_ Serovar Hardjo Seroprevalence and Farming Practices on

Small-Scale Dairy Farms in North Eastern India; Insights Gained from a Cross-Sectional Study. _Dairy_ 2, 231–241. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy2020020 (2021). Article Google Scholar *

Rypuła, K. _et al._ Prevalence of antibodies to _Leptospira hardjo_ in bulk tank milk from unvaccinated dairy herds in the south-west region of Poland. _Berliner und Munchener tierarztliche

Wochenschrift_ 127, 247–250 (2014). PubMed Google Scholar * Motto, S. K. _et al._ Seroepidemiology of _Leptospira_ serovar Hardjo and associated risk factors in smallholder dairy cattle in

Tanzania. _PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis._ 17, e0011199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011199 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gamage, C. D. _et al._ Prevalence and

carrier status of leptospirosis in smallholder dairy cattle and peridomestic rodents in Kandy, Sri Lanka. _Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis._ 11, 1041–1047. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2010.0153

(2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * dos Santos, J. P. _et al._ Seroprevalence and risk factors for Leptospirosis in goats in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. _Trop. Anim. Health

Prod._ 44, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-011-9894-1 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Desa, G., Deneke, Y., Begna, F. & Tolosa, T. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk

Factors of _Leptospira interrogans_ Serogroup Sejroe Serovar Hardjo in Dairy Farms in and around Jimma Town, Southwestern Ethiopia. _Vet. Med. Int._ 2021, 6061685.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6061685 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Selim, A. & Abdelhady, A. Neosporosis among Egyptian camels and its associated risk

factors. _Trop. Anim. Health Prod._ 52, 3381–3385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02370-y (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Selim, A. _et al._ Prevalence and animal level risk

factors associated with _Trypanosoma evansi_ infection in dromedary camels. _Sci. Rep._ 12, 8933. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12817-x (2022). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Ellis, W. A. Leptospirosis as a cause of reproductive failure. _Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract._ 10, 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30532-6 (1994).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fávero, J. F. _et al._ Bovine leptospirosis: Prevalence, associated risk factors for infection and their cause-effect relation. _Microbial

Pathogenesis_ 107, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.032 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pratt, N. & Rajeev, S. _Leptospira_ seroprevalence in animals in the

Caribbean region: A systematic review. _Acta Tropica_ 182, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.02.011 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Suepaul, S. M., Carrington, C.

V., Campbell, M., Borde, G. & Adesiyun, A. A. Seroepidemiology of leptospirosis in livestock in Trinidad. _Trop. Anim. Health Prod._ 43, 367–375.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-010-9698-8 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Marzok, M., Hereba, A. M. & Selim, A. Equine leptospirosis in Egypt: Seroprevalence and risk factors.

_Slovenian Vet. Res._ 60, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.26873/SVR-1716-2023 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Parvez, M. A., Prodhan, M. A. M., Rahman, M. A. & Faruque, M. R.

Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of _Leptospira interrogans_ serovar Hardjo in dairy cattle of Chittagong, Bangladesh. _Pak. Vet. J._ 35, 350–354 (2015). Google Scholar * Veena,

S. Investigation on the Distribution of Leptospira Serovars and its Prevalence in Bovine in Konkan Region, Maharashtra, India. _Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci._ 4, 19–26.

https://doi.org/10.14737/journal.aavs/2016/4.2s.19.26 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Ijaz, M. _et al._ Sero-epidemiology and hemato-biochemical study of bovine leptospirosis in flood

affected zone of Pakistan. _Acta Trop_ 177, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.09.032 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hegazy, Y. _et al._ Leptospirosis as a

neglected burden at human-cattle interface in Mid-Delta of Egypt. _J. Infect. Dev. Countries_ 15, 704–709. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.13231 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Suwancharoen,

D., Chaisakdanugull, Y., Thanapongtharm, W. & Yoshida, S. Serological survey of leptospirosis in livestock in Thailand. _Epidemiol. Infect._ 141, 2269–2277.

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268812002981 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Benseghir, H., Amara-Korba, A., Azzag, N., Hezil, D. & Ghalmi, F. Seroprevalence of and

associated risk factors for _Leptospira interrogans_ serovar Hardjo infection of cattle in Setif, Algeria. _Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol._ 21, 185–191 (2020). Google Scholar * Higgins, R.

J., Harbourne, J. F., Little, T. W. & Stevens, A. E. Mastitis and abortion in dairy cattle associated with _Leptospira_ of the serotype hardjo. _Vet. Rec._ 107, 307–310.

https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.107.13.307 (1980). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Orjuela, A. G., Parra-Arango, J. L. & Sarmiento-Rubiano, L. A. Bovine leptospirosis: Effects on

reproduction and an approach to research in Colombia. _Trop. Anim. Health Prod._ 54, 251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-022-03235-2 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Boey, K., Shiokawa, K. & Rajeev, S. _Leptospira_ infection in rats: A literature review of global prevalence and distribution. _PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis._ 13, e0007499.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007499 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ribeiro, P. _et al._ Seroepidemiology of leptospirosis among febrile patients in a

rapidly growing suburban slum and a flood-vulnerable rural district in Mozambique, 2012–2014: Implications for the management of fever. _Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc.

Infect. Dis._ 64, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2017.08.018 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the

Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia for the financial support of this research through the

Grant Number 5858. FUNDING This work was supported through the Annual Funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King

Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant Number 5858). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Animal Medicine (Infectious Diseases), Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Benha

University, Toukh, 13736, Egypt Abdelfattah Selim * Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, 31982, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia Mohamed Marzok

& Mohamed Salem * Department of Surgery, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kafr El Sheikh University, Kafr El Sheikh, Egypt Mohamed Marzok * Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences,

Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Hattan S. Gattan * Special Infectious Agents Unit, King Fahad Medical Research Center, King AbdulAziz

University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Hattan S. Gattan * Department of Parasitology and Animal Diseases, National Research Center, Giza, Egypt Abdelhamed Abdelhady * Department of Biomedical

Physics, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt Abdelrahman M. Hereba * Department of Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo

University, 12613, Cairo, Egypt Mohamed Salem * Department of Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, 31982, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia Abdelrahman M. Hereba Authors

* Abdelfattah Selim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mohamed Marzok View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Hattan S. Gattan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Abdelhamed Abdelhady View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mohamed Salem View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Abdelrahman M. Hereba View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation,

writing-original draft preparation, A.S., A.A., H.S.G., A.M,H., M.M., and M.S.; writing-review and editing, A.S., A.A., H.S.G., A.M,H., M.M., and M.S.; project administration, M.M.; funding

acquisition, A.S., A.A., H.S.G., A.M,H., M.M., and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Abdelfattah Selim

or Mohamed Marzok. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with

regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's

Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not

permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Selim, A., Marzok, M., Gattan, H.S. _et al._ Seroprevalence and associated risk

factors for bovine leptospirosis in Egypt. _Sci Rep_ 14, 4645 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54882-4 Download citation * Received: 22 October 2023 * Accepted: 17 February 2024 *

Published: 26 February 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54882-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable

link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * _Leptospira_ spp *

Serology * Risk factors * Cattle * Egypt