Advanced antireflection for back-illuminated silicon photomultipliers to detect faint light

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Silicon photomultipliers have attracted increasing attention for detecting low-density light in both scientific research and practical applications in recent years; yet the photon

losses due to reflection on the light-sensitive planar silicon surface considerably limit its photon detection efficiency. Here we demonstrate an advanced light trapping feature by

developing the multi-layer antireflection coatings and the textured silicon surface with upright random nano-micro pyramids, which significantly reduces the reflection of faint light in a

wide spectrum, from ultraviolet to infrared. Integrating this advanced photon confinement feature into next-generation back-illuminated silicon photomultiplier would increase the photon

detection efficiency with significantly lower reflection and much more active areas. This advanced design feature offers the back-illuminated silicon photomultiplier broader application

opportunities exemplified in the emerging scenarios such as nuclear medical imaging, light detection and ranging for autonomous driving, detection of scintillation light in ionizing

radiation, as well as high energy physics. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ULTRAHIGH-SPEED POINT SCANNING TWO-PHOTON MICROSCOPY USING HIGH DYNAMIC RANGE SILICON PHOTOMULTIPLIERS

Article Open access 04 March 2021 QUANTUM MICROSCOPY BASED ON HONG–OU–MANDEL INTERFERENCE Article 11 April 2022 DEVICE RESPONSE PRINCIPLES AND THE IMPACT ON ENERGY RESOLUTION OF EPITAXIAL

QUANTUM DOT SCINTILLATORS WITH MONOLITHIC PHOTODETECTOR INTEGRATION Article Open access 02 October 2024 INTRODUCTION Silicon photomultipliers (SiPM) are the cornerstones of photodetector

technologies for detecting faint light in both industry and scientific research since their early development in 1990s1,2,3,4,5. Their attractive performances have brought benefits into

emerging applications, such as ionizing radiation detection, biomedical imaging, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) for autonomous driving6. Compared to photomultiplier tube (PMT) that

is a conventional photodetector legacy technology in the radiation detection, SiPM offers several advantages, including low operation voltage, compactness, ruggedness, and relatively low

cost7. Furthermore, in contrast to PMT, SiPM is insensitive to magnetic fields, which leads to its vital role as the foundation of light detection technology for the advanced medical

equipment in the presence of magnetic fields, such as positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. However, the photon detection efficiency (_PDE_) that is defined as the ratio between the

numbers of detected photons and the photons arriving at the detector, which is also one of the key measurable metrics that quantify SiPM’s performance, is still limited to about 60% and

rapidly decreases from the peak as the wavelength enters into the ultraviolet range5,8. This is due to not only the reflection losses of photons impinging on the front planar silicon

surface, but also the limited fill factor (_FF_) caused by the dead areas (_i.e._, quenching resistor, isolation trench, guard ring, and contact metal) for the conventional front-illuminated

structure, in addition to the recombination loss of the photo-generated primary carriers near defect centers9. Therefore, a reduction in photon reflection at the surface is a prominent role

in the development of high-performance SiPM devices. In order to reduce the photon losses due to reflection, the approach of antireflection coatings (ARC) is typically used, because it can

reduce the photon losses by making use of phase changes and the dependence of the reflectivity on refractive index10. In addition to the proper refractive index and film thickness, a low

extinction coefficient (_κ_) is also required for the ARC material to avoid a significant photon absorption by the ARC thin-film layer. The ARC materials used in conventional SiPM are

thermally grown silicon dioxide (SiO2), and silicon nitride (SiNx) that can be deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) as single-layer ARC (SARC) on planar

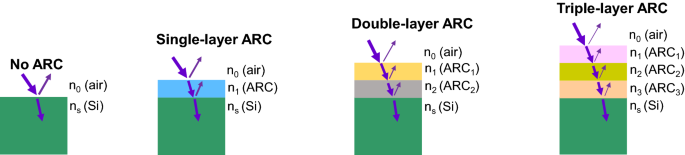

surface2,7,11. In this work, we developed multi-layer ARC on textured surface with upright nano-micro pyramids to reduce the reflection, including double-layer ARC (DARC) and triple-layer

ARC (TARC). For comparison purpose, the single-layer ARC as well as the bare silicon wafer without ARC on both planar and textured surfaces are also studied in this work. In the end, the

back-illuminated SiPM integrated with the multi-layer ARC on textured surface are discussed, as a comparison to the conventional SiPM with ARC on planar surface. RESULTS CONVENTIONAL

SINGLE-LAYER ANTIREFLECTION COATING According to the theory of quarter-wave dielectric layer12,13, the reflection of incident beam of light reflected from the surface of a single-layer ARC

deposited on a substrate material has its minimum value when: $$ n_{1} = \sqrt {n_{0} n_{s} } $$ (1) $$ n_{1} d_{1} = \lambda_{0} /4 $$ (2) where _n__0_, _n__1_, and _n__s_ represent the

refractive indices of medium (air in this work), ARC material, and absorption substrate material (silicon in this work), respectively. _d__1_ is the thickness of ARC layer, and _λ__0_ is the

wavelength of incident light with minimum reflection. For a SiPM in air (_n__0_ = 1.0, and _n__s_ = 3.8), the optimum refractive index of single-layer ARC is _n__1_ ≈ 1.9. Note that the

specific refractive index values given in this work are measured at the wavelength of 632 nm. Therefore, this work applied the conventional single-layer ARC material SiNx as a reference due

to its refractive index of 1.96 close to the optimum value, and the SiO2 was also included as a comparison because it is typically used as a surfa passivation material as well as an ARC

material at the same time for the early SiPM studies2,7. Figure 1 shows the schematic of single-layer ARC on silicon wafers in this study, the case of no ARis also included. Figure 2 shows

that the 55-nm SiNx deposited on planar silicon surface as a single-layer ARC can minimize the reflection close to zero at the wavelength of 450 nm, which is in good agreement with the

condition Eqs. (1)–(2). The “thicker” SiNx (72 nm) shifts the reflection curve to higher wavelength with the minimum reflection close to zero at around 600 nm, while the “thinner” SiNx (38

nm) results in the minimum reflection of still over 5% at about 340 nm, suggesting the thickness of 38 nm is too thin for SiNx as a single-layer ARC. It is also indicated in Fig. 2 that the

average reflection of all studied SiNx films as single-layer ARC measured in the spectrum of 200–800 nm are all over 15%, although the minimum reflection can be reduced to zero at certain

wavelength by changing the SiNx thickness. Although SiO2 demonstrates a better surface passivation function than SiNx due to lower interface defect density14, and the earlier SiPM studies

use it as a surface passivation layer as well as a single-layer ARC2, Fig. 3 clearly shows that SiO2 has inferior antireflection performance over the studied spectrum. Compared to the case

of without any ARC (bare silicon surface), SiO2 does reduce the reflection shown in Fig. 3, and the average reflection is reduced from 47.4% to 28.5%. However, it is still much higher than

that of SiNx (18.4%), as summarized by the insert table in Fig. 3. Therefore, Fig. 3 reveals that SiO2 is not a proper ARC material, and SiNx as a single-layer ARC is still not sufficient to

reduce photon losses for high-performance next-generation SiPM devices. MULTI-LAYER ARC: DOUBLE-LAYER ARC AND TRIPLE-LAYER ARC Although a single-layer ARC is able to minimize the reflection

down to zero at a specific wavelength when it meets the conditions as given by Eqs. (1) and (2), its reflections at other wavelengths are still high because its refractive index is

wavelength-dependent. Therefore, to reduce the reflection over a wide spectrum of 200 ~ 800 nm, this work developed multi-layer ARC, including double-layer ARC and triple-layer ARC, as shown

in Fig. 1. The multi-layer ARC feature can decrease the reflection at the surface because of the interference of the reflected light from each interface. This work applied the transfer

matrix method (TMM)10,15 in addition to the theory of quarter-wave dielectric layers to determine the multi-layer ARC materials and their thickness. For the double-layer ARC feature, to

minimize the average reflection over a wide spectrum, the selected ARC materials should meet the conditions: $$ n_{1} = \sqrt[3]{{n_{0}^{2} \cdot n_{s} }} $$ (3) $$ n_{2} = \sqrt[3]{{n_{0}

\cdot n_{s}^{2} }} $$ (4) $$ d_{j} = \frac{{\lambda_{0} }}{{4n_{j} }} $$ (5) where _n__0_, _n__1_, _n__2_, and _n__s_ represent the refractive dices of each layer as shown in Fig. 1, and

_d__j_ (_j_ = 1, and 2) is the thickness of ARC layer. Therefore, according to the conditions (3) and (4), magnesium fluoride (MgF2, _n__1_ = 1.37) and zinc sulfide (ZnS, _n__2_ = 2.33) are

selected as constituent layers of the double-layer ARC feature in this work. Similarly, for the triple-layer ARC feature, the following conditions of refractive indices of the selected ARC

materials should be met to minimize the average reflection over a wide spectrum: $$ n_{1} = \sqrt[4]{{n_{0}^{3} \cdot n_{s} }} $$ (6) $$ n_{2} = \sqrt {n_{0} \cdot n_{s} } $$ (7) $$ n_{3} =

\sqrt[4]{{n_{0} \cdot n_{s}^{3} }} $$ (8) where _n__0_, _n__1_, _n__2_, _n__3_, and _n__s_ are the refractive indices of each layer as shown in Fig. 1. The thickness of each layer _d__j_

(_j_ = 1, 2, and 3) can be determined by Eq. (5). So, this work investigated MgF2 (_n__1_ = 1.37), HfO2 (_n__2_ = 1.91), and TiO2 (_n__3_ = 2.49) for the triple-layer ARC feature. Figure 4

shows that double-layer ARC reduces the reflection for most wavelengths, compared to SiNx as single-layer ARC, especially in the ultraviolet (UV) range, with the minimum reflection close to

zero at round 320 nm. Its resulted average reflection also decreases to 11.2%. However, its reflection at wavelength below 280 nm is still high (over 15%), and even higher than that of SiNx

at below 250 nm. Therefore, this work develops the textured surface in combination with multi-layer ARC features to enhance the light trapping and hence reduce the photon losses. TEXTURED

SURFACE WITH UPRIGHT RANDOM NANO-MICRO PYRAMIDS FORMED BY ANISOTROPIC ETCHING To enhance the light trapping on silicon wafer, texturing the wafer surface by an anisotropic etching to obtain

upright random nano-micro pyramidal structures16,17 is an effective approach to reduce the surface reflection. As shown Fig. 5, compared to the planar surface where the light reflected from

the surface is completely lost, the textured surface can allow the light reflected from the side of one of pyramids to be reflected downward, and then getting a second chance of being

absorbed into the silicon bulk. The formation of these random arrays of ideal {111} faceted upright pyramids on the etched surface is driven by the anisotropic nature of the chemical

etchant, that is, the etch rate in the < 100 > direction of single crystalline silicon is several times greater than that in the < 111 > direction. The higher etch rate in the

< 100 > direction is because the {100} surface requires the lower activation energy to remove an atom than the {111} surface18. This is because the {100} surface only needs to break

two back bonds rather than three ones in the case of {111} surface19. Note that each atom of Si {111} surface has three back bonds and one dangling bond, but each atom of {100} surface has

two back bonds and two dangling ones. Therefore, the upright pyramids are formed by the intersection of (100) and (111) planes as the consequence of anisotropic etching of silicon (100)

substrate due to the slowest etching rate of {111} crystallographic planes. Figure 6 displays the surface morphology of etched silicon (100) wafers by scanning electron microscope (SEM)

images taken on the textured surface after the anisotropic etching. The appearance of the upright random nano-micro pyramids is clearly seen from these SEM images. The sizes of these

pyramids are random, in the range of a few hundreds of nanometers to a couple of microns. These upright pyramids are formed due to the anisotropic etching of silicon (100) substrate, which

are bounded by {111} crystallographic planes because of the slowest etching rate of {111} planes18. The image (a) is obtained from the top view, showing the pyramid tips as shining points

and the pyramid base borders as black lines, while the resulted image (b) gives a more straightforward view after tilting the sample at -5°. From the side view and tilting the sample at 30°,

image (c) shows an art-like overview of resulted upright pyramids, and image (d) gives a closer look after increasing the SEM resolution. As shown in Fig. 7, the textured bare surface has

much lower reflection than the planar bare surface over the entire spectrum, because it allows the light reflected from the side of pyramids to be reflected downward and hence get a second

chance of being absorbed into silicon, as demonstrated in Fig. 5. This leads to its average reflection of only 18.6%, a dramatical decrease from that of the planar surface (47.4%). Figure 7

also indicates that the reflection reduction between the textured and planar surfaces is almost similar for all wavelengths because of the same light trapping mechanism regardless of the

wavelength. To further reduce the reflection, various ARC dielectric stacks are deposited on the textured surface to combine the antireflection benefits of both the textured surface and the

ARC feature. MULTI-LAYER ARC ON TEXTURED SURFACE It is shown in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 that the single-layer ARC (SiNx) on textured surface provides a dramatical decrease in reflection, compared

to the bare textured surface. Its reflection is close to zero for the wavelength above 400 nm, while it bumps up in the UV range, and peaks at over 27% around 275 nm. These result in its

average reflection of 5.0% on textured surface, an effective improvement from the same ARC feature on planar surface (18.4%) shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. Having the reflection as low as the

single-layer ARC for the wide spectrum from blue light to red light, the double-layer ARC (MgF2/ZnS) on textured surface cuts down significantly the reflection for the UV light, as shown in

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8. However, its reflection gradually increases at wavelength below 260 nm, and saturates at approximately 9% around 200 nm. These lead to a very low average reflection of

2.3%, compared to 11.2% for the same double-layer ARC feature on planar surface listed in Fig. 4, a very impressive enhancement in antireflection. Figure 7 and Fig. 8 display that the

triple-layer ARC (MgF2/HfO2/TiO2) on textured surface can reduce the reflection down to less than 1% for the wavelengths below 260 nm, which is a very promising enhancement, compared to the

double-layer ARC feature. Its reflection also is marginally lower at the wavelength above 500 nm than the double-layer ARC, but bumps up in the range of 300 ~ 420 nm, and peaks at 6.5%

around 360 nm. These result in an average reflection of 1.5%, the lowest among the studied antireflection features in this work. Figure 9 summarizes the average reflections of

single/double/triple-layer ARC on planar and textured surfaces, as well as the bare planar and textured surfaces without ARC. It clearly displays that all ARC features on textured surface

have lower average reflection than their counterparts on planar surface. In addition, the multi-layer ARC features can reduce the average reflection more than the single-layer ARC regardless

of the silicon wafer surface tomography, either planar or textured, as shown in Fig. 9. When SiPM is coupled with a scintillator for radiation detection applications, the sensitive

wavelength of SiPM must match with the emission wavelength of scintillators. For example, barium fluoride (BaF2) scintillators are among the fastest scintillators with sub-nanosecond decay

time for emitted “fast” pulses at wavelength of 220 nm, and widely used in the applications of time-of-flight measurement, PET, nuclear and high energy physics20. Therefore, in order to

detect these “fast” pulses emitted from BaF2 scintillators, the triple-layer ARC on textured surface would be a better feature than the double-layer ARC, because it enables lower reflection

at wavelength range of 220 nm shown in Fig. 8, and hence potentially higher _PDE_. While detecting the photons with wavelength in the range of 300 ~ 420 nm, i.e., emitted from cesium

fluoride (CsF), cerium fluoride (CeF3), and yttrium orthoaluminate (YAlO3) scintillators20, the double-layer ARC on textured surface may be a competitive option, but the triple-layer ARC on

textured surface is still a better feature for detecting photons with wavelength over 460 nm, i.e., coming from Y3A15O12 and CsI:Tl scintillators21. In the next section, we will discuss more

about the back-illuminated SiPM with the multi-layer ARC on textured surface. DISCUSSION Figure 10 shows the schematic of conventional front-illuminated SiPM with SiNx as single-layer ARC

on planar surface where photons are incident. As a solid-state photodetector, SiPM is segmented in tiny Geiger-mode Avalanche Photodiodes (GM-APD), also called microcells. The cross-section

of a microcell of this SiPM structure is enlarged and shown in Fig. 11 (left). The _pn_-junction of microcell is formed on the top of epitaxial layer that is grown on the _n_-type Si wafer

substrate to create a high-field region for the Geiger-mode avalanche events via a sufficient bias voltage. The Al2O3 thin film acts as an excellent passivation layer to passivate the

surface defects (i.e., dangling bonds) to suppress the carrier recombination by its low interface defect density and built-in negative fixed charges at the interface to shield the electron

carriers14. The front contact metal is connected to the positively-doped emitter layer (_p_+) and the quenching resistor that is used to turn off the avalanche current to reduce the

operating voltage down to below the breakdown voltage, so that the microcell can be restored to its initial status and get ready to detect a new event. Through the quenching resistors, each

microcell is connected in parallel to the front buried metal grid. The isolation trenches between microcells are introduced to minimize the optical cross-talk effect that is one of noise

sources, but it reduces the total active areas and hence the _FF_. In addition, the guard ring structure at the edge area with lower doping level (_p__-_) than the active area (_p_+) can

prevent an edge premature breakdown, but induces a reduction in the active area. As a consequence, this conventional front-illuminated SiPM structure has not only a high photon reflection

due to the ARC on planar surface but also a limited _FF_ due to the dead areas (i.e., quenching resistor, front contact mental, isolation trench, and guard ring) on the detector side where

the photons are incident, which limits quantum efficiency (_QE_) and hence _PDE_. Therefore, this work investigates the back-illuminated SiPM with multi-layer ARC on textured surface. Figure

11 compares the microcell cross-sections of the conventional front-illuminated SiPM with ARC on planar surface and the back-illuminated SiPM with multi-layer ARC on textured surface that is

developed in this work. For the conventional front-illuminated SiPM, the incoming photons are incident on the planar surface coated by ARC, being on the same side as the avalanche regions

(high electrical field regions). In contrast, for the back-illuminated SiPM, the incoming photons fall on the detector side opposite to the avalanche regions22,23,24. The multilayer ARC on

textured surface developed in this work is designed on the detector side of back-illuminated SiPM shown in Fig. 11, directly facing the incoming photons. As shown in Fig. 8, the multi-layer

ARC on textured surface has much lower reflection over the entire spectrum than the SiPM array that has the conventional front-illuminated structure with ARC on planar surface. Note that

this SiPM array is SensL J-Series sensors (635J1) with microcell size of 35 × 35 μm2, _FF_ of 75%, the maximum _PDE_ of 50% at 420 nm, dark count rate of 150 kHz/mm2, and gain of 6.3 × 106.

The resulted average reflection of this SiPM array is 18.9%, much higher than those of the multi-layer ARC on textured surface, 2.3% for the double-layer ARC and 1.5% for the triple-layer

ARC. So, applying the multi-layer ARC on textured surface to the back-illuminated SiPM can reduce dramatically its reflection and hence potentially boost its _PDE_ and _QE_ that is defined

as the probability for an incident photo to generate a primary electron–hole pair and subsequent collection of photogenerated carriers in the active area of the SiPM device. In addition, as

the dead areas (including quenching resistor, isolation trench, and guard ring) are relocated to the microcell’s bottom side, the back-illuminated SiPM structure has more active areas on the

top side where photons are incident, which leads to a much higher _FF_, compared to the conventional front-illuminated structure that typically limits the _FF_ to 80% or even much lower for

smaller microcell sizes. Combining the high _FF_ (potentially close to 100%) and the low reflection as described above, the back-illuminated SiPM structure with multi-layer ARC on textured

surface shown in Fig. 11 would improve the _PDE_ to a very promising level. In conclusion, this work has demonstrated that the multi-layer ARC on textured silicon surface with upright random

nano-micro pyramids can dramatically reduce the reflection over a wide spectrum, compared to the conventional single-layer ARC on planar surface for SiPM. On the planar silicon surface,

SiNx as the conventional single-layer ARC has a better antireflection performance than SiO2 due to its optimum refractive index, and can minimize the reflection down close to zero at

specific wavelengths for the optimum film thickness, but its average reflection of 18.4% is higher than that of the multi-layer ARC (about 11%). The textured surface can be formed by the

anisotropic etching of silicon (100) substrate in alkaline solution due to the slowest etching rate of {111} crystallographic planes, and lead to significantly lower reflection than the

planar surface regardless of the wavelength, resulting in the average reflection of 18.6% vs 47.4%. This is due to its powerful light trapping feature that allows the light reflected from

the side of pyramids to be reflected downward and get a second chance of being coupled into silicon. The combined feature of the multi-layer ARC deposited on the textured surface empowers

the light trapping performance even further by reducing the average reflection down to 2.3% for the double-layer ARC (MgF2/ZnS), and 1.5% for the triple-layer ARC (MgF2/HfO2/TiO2), which is

lower than that of the single-layer ARC on textured surface (5.0%). Compared to the conventional front-illuminated SensL SiPM array with ARC on planar surface that have an average reflection

of 18.9%, a _FF_ of 75%, and a state-of-the-art _PDE_ of 50%, our back-illuminated SiPM with the multi-layer ARC on textured surface would increase the _PDE_ to a very promising level by

the ultra-low average reflection of 1.5% and the much higher _FF_ (potentially approach to 100%) due to the elimination of the dead areas from the detector side. Benefiting from its

reflection close to zero for the wavelength range of 200 ~ 300 nm, the studied feature of the multi-layer ARC on textured surface might enable the back-illuminated SiPM to effectively detect

the “fast” pulses with sub-nanosecond decay time at wavelength of 220 nm emitted from one of the fastest scintillators BaF2, which paves a way to facilitate its broad applications, such as

time-of-flight measurement, PET, scintillation light detection in ionizing radiation, nuclear and high energy physics. METHODS The silicon wafers used in this study are polished float-zone

4-inch _n_-type (100) wafers with thickness of 280 μm. The wafers were processed in a 5% hydrogen fluoride (HF) solution prior to depositing ARC thin films. The SiNx dielectric thin films

were deposited by PECVD at 250 °C with precursors of nitrogen, silane, and ammonia. Three different thicknesses of SiNx films are compared, including a designated thickness of 55 nm in order

to detect the photons emitted from conventional scintillators with wavelength around 450 nm, a “thicker” film of 72 nm, and a “thinner” one of 38 nm. The 78-nm SiO2 films (refractive index

_n__SiO2_ = 1.46) used to compare SiNx in the single-layer ARC feature were also deposited by PECVD at 250 °C with precursors of nitrogen, silane, and nitrous oxide. For the multi-layer ARC

features, zinc sulphide (ZnS, refractive index _n__ZnS_ = 2.20) and magnesium fluoride (MgF2, refractive index _n__MgF2_ = 1.37) thin films were grown by a thermal-evaporator at the voltages

of 15 V and 10 V and the deposition rate of 2 Å/s, with the film thicknesses of 48 nm and 77 nm. Titanium oxide (TiO2, refractive index _n__TiO2_ = 2.49) and hafnium oxide (HfO2, refractive

index _n__HfO2_ = 1.91) thin films are deposited by an E-beam evaporator at the deposition rate of 0.5 Å/s. The film thicknesses of triple-layer ARC are 42, 55, and 77 nm for TiO2, HfO2,

MgF2, respectively. Note that the physical vapor deposition (PVD) techniques used this work are the thermal-evaporator and the E-beam evaporator, which are less conformal than the chemical

vapor deposition (CVD) or the atomic-layer deposition (ALD) techniques. However, because the pyramids with feature base angle of about 54° formed on the silicon wafer surface are in the

scale of one micron while the ARC thickness in this study is in the scale of 100 nm, the applied deposition technique would have negligible impact on the reflection measurement results.

After the ARC depositions, the wafers were characterized by a Cary 5000 UV–Vis/NIR spectrophotometer to measure the total reflectance (specular and scattering) in the wide spectrum of 200 ~

800 nm, which is enabled by using a combination of a tungsten halogen and deuterium arc light source to illuminate the samples. The anisotropic etching was performed in the 3% (volume ratio)

potassium hydroxide (KOH) alkaline and 4% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and deionized (DI) water mixture solutions at a high temperature of 80 °C for 20 min. After the texturing, the wafers were

cleaned in a 5% HF solution. Note that all the wet chemical processing and the thin film depositions were performed in the specialized class 100 cleanrooms to avoid contaminations. This work

used the scanning electron microscope (SEM) technique at 5 kV to characterize the surface features after the texturing process. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this

study are available from the corresponding author on request. REFERENCES * Bisello, D. _et al._ Silicon avalanche detectors with negative feedback as detectors for high energy physics.

_Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A_ 367(1–3), 212–214 (1995). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Antich, P. P., Tsyganov, E. N., Malakhov, N. A. & Sadygov, Z. Y. Avalanche

photo diode with local negative feedback sensitive to UV, blue and green light. _Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A_ 389(3), 491–498 (1997). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Buzhan, P. _et al._ Silicon photomultiplier and its possible applications. _Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A_ 504(1–3), 48–52 (2003). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Roncali,

E. & Cherry, S. R. Application of silicon photomultipliers to positron emission tomography. _Ann. Biomed. Eng._ 39(4), 1358–1377 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Sadygov, Z., Sadigov,

A. & Khorev, S. Silicon photomultipliers: Status and prospects. _Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett._ 17(2), 160–176 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Li, Y. & Ibanez-Guzman, J. Lidar for

autonomous driving: The principles, challenges, and trends for automotive lidar and perception systems. _IEEE Signal Process. Mag._ 37(4), 50–61 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Renker, D.

Geiger-mode avalanche photodiodes, history, properties and problems. _Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A_ 567(1), 48–56 (2006). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Nagai, A. _et

al._ SENSE: A comparison of photon detection efficiency and optical crosstalk of various SiPM devices. _Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detectors Assoc. Equip._

912, 182–185 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Piemonte, C. & Gola, A. Overview on the main parameters and technology of modern Silicon Photomultipliers. _Nucl. Instrum.

Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A_ 926, 2–15 (2019). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Zhao, J. & Green, M. A. Optimized antireflection coatings for high-efficiency silicon solar cells.

_IEEE Trans. Electron Devices_ 38(8), 1925–1934 (1991). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Dinu, N., 2016. Silicon photomultipliers (SiPM). In _Photodetectors_ (pp. 255–294). Woodhead

Publishing. * Heavens, O.S., 1991. Optical properties of thin solid films. Courier Corporation. * Green, M.A., 1982. Solar cells: operating principles, technology, and system applications.

_Englewood Cliffs_. * Tao, Y. & Erickson, A. Enhanced surface passivation by atomic layer deposited Al2O3 for ultraviolet sensitive silicon photomultipliers. _IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci._

69(2), 187–191 (2022). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Saylan, S. _et al._ Multilayer antireflection coating design for GaAs0. 69P0. 31/Si dual-junction solar cells. _Sol. Energy_ 122,

76–86 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Campbell, P. & Green, M. A. Light trapping properties of pyramidally textured surfaces. _J. Appl. Phys._ 62(1), 243–249 (1987). Article

ADS Google Scholar * Baker-Finch, S. C. & McIntosh, K. R. Reflection distributions of textured monocrystalline silicon: Implications for silicon solar cells. _Prog. Photovoltaics

Res. Appl._ 21(5), 960–971 (2013). Google Scholar * Seidel, H., Csepregi, L., Heuberger, A. & Baumgärtel, H. Anisotropic etching of crystalline silicon in alkaline solutions: I.

Orientation dependence and behavior of passivation layers. _J. Electrochem. Soc._ 137(11), 3612 (1990). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Chen, W. _et al._ Difference in anisotropic

etching characteristics of alkaline and copper based acid solutions for single-crystalline Si. _Sci. Rep._ 8(1), 1–8 (2018). ADS Google Scholar * Blasse, G. Scintillator materials. _Chem.

Mater._ 6(9), 1465–1475 (1994). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yanagida, T. Inorganic scintillating materials and scintillation detectors. _Proc. Japan Acad. Ser. B_ 94(2), 75–97 (2018).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Otte, A. N. _et al._ Prospects of using silicon photomultipliers for the astroparticle physics experiments EUSO and MAGIC. _IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci._

53(2), 636–640 (2006). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Moser, H.G., Hass, S., Merck, C., Ninkovic, J., Richter, R., Valceanu, G., Otte, N., Teshima, M., Mirzoyan, R., Holl, P. and

Koitsch, C., 2007, June. Development of back illuminated SiPM at the MPI semiconductor laboratory. In _Proceedings of International Workshop New Photon-Detectors_ (pp. 1–7). * Hu, H. _et

al._ Advanced back-illuminated silicon photomultipliers with surrounding P+ trench. _IEEE Sens. J._ 2, 440. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3188692 (2022). Article Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Energy/National Nuclear Security Administration under Award Number(s) DE-NA0003921. The

authors would like to thank Dr. Ajeet Rohatgi and Brian Rounsaville at the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and the technical staffs at the Institute for Electronics and

Nanotechnology (IEN) at Georgia Institute of Technology for their supports. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Nuclear and Radiological Engineering, Georgia Institute of

Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA Yuguo Tao, Arith Rajapakse & Anna Erickson Authors * Yuguo Tao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Arith

Rajapakse View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anna Erickson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS A.E. and Y.T. developed the project. A.R. performed the SEM characterization. Y.T. performed the fabrication and characterization. All authors analyzed the results,

prepared conclusions, and contributed to the paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Yuguo Tao. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or

format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or

other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission

directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Tao, Y.,

Rajapakse, A. & Erickson, A. Advanced antireflection for back-illuminated silicon photomultipliers to detect faint light. _Sci Rep_ 12, 13906 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18280-y Download citation * Received: 01 June 2022 * Accepted: 09 August 2022 * Published: 16 August 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18280-y

SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy

to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative