Nighttime smartphone use and changes in mental health and wellbeing among young adults: a longitudinal study based on high-resolution tracking data

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Frequent nighttime smartphone use can disturb healthy sleep patterns and may adversely affect mental health and wellbeing. This study aims at investigating whether nighttime

smartphone use increases the risk of poor mental health, i.e. loneliness, depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and low life satisfaction among young adults. High-dimensional tracking data

from the Copenhagen Network Study was used to objectively measure nighttime smartphone activity. We recorded more than 250,000 smartphone activities during self-reported sleep periods among

815 young adults (university students, mean age: 21.6 years, males: 77%) over 16 weekdays period. Mental health was measured at baseline using validated measures, and again at follow-up four

months later. Associations between nighttime smartphone use and mental health were evaluated at baseline and at follow-up using multiple linear regression adjusting for potential

confounding. Nighttime smartphone use was associated with a slightly higher level of perceived stress and depressive symptoms at baseline. For example, participants having 1–3 nights with

smartphone use (out of 16 observed nights) had on average a 0.25 higher score (95%CI:0.08;0.41) on the Perceived stress scale ranging from 0 to 10. These differences were small and could not

be replicated at follow-up. Contrary to the prevailing hypothesis, nighttime smartphone use is not strongly related to poor mental health, potentially because smartphone use is also a

social phenomenon with associated benefits for mental health. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SELF-REPORTED AND TRACKED NIGHTTIME SMARTPHONE USE AND THEIR ASSOCIATION WITH OVERWEIGHT

AND CARDIOMETABOLIC RISK MARKERS Article Open access 28 February 2024 A TRANSLATIONALLY INFORMED APPROACH TO VITAL SIGNS FOR PSYCHIATRY: A PRELIMINARY PROOF OF CONCEPT Article Open access 26

August 2024 MONITORING SLEEP USING SMARTPHONE DATA IN A POPULATION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS Article Open access 17 March 2023 INTRODUCTION Mental health problems are recognized as a major burden

of disease, and a substantial number of adults struggle with mental health problems1. In many Western societies, an increase in poor mental health has been detected in particular among

young adults during the last decades2,3. During the same period advances in smartphone technologies have become increasingly available causing widespread and round-the-clock use of

smartphones especially among the younger generations4,5. The parallel increase in both smartphone use and poor mental health in western societies is striking and draws attention to excessive

smartphone use as a potential risk factor for poor mental health6,7. In particular, the frequent nighttime smartphone use may disturb sleep and thereby adversely affect mental health8. As

part of the sustainable development goals, the United Nations has proclaimed to promote mental health and wellbeing by 20309. However, research is yet to identify modifiable risk factors

that can be easily targeted in mental health interventions. Considering the widespread nighttime smartphones use even small effects on mental health can have major public health

implications. Specifically preventing nighttime smartphone use may be a tangible population behaviour change as it requires a relatively simple change for the individual such as turning off

the smartphone at night or leaving the smartphone out of the bedroom10. Hence, it is relevant to investigate whether and how nighttime smartphone use may affect mental health. The use of

light-emitting electronic devices before and during the sleep period is likely to stimulate cognitive arousal and delay the release of the sleep hormone melatonin affecting both sleep onset

latency and sleep perceptions11,12,13,14. Prolonged sleep disruptions are likely to interfere with mental restitution15,16 and mood17, and several studies have shown that poor sleep plays an

important etiological role in the development of poor mental health working through changed emotional regulation and neuro-biological interaction18,19,20. Poor sleep quality has shown to

either affect or exacerbate feelings of perceived stress21, which may over a longer period develop into depressive symptoms22. Further, sleep deprivation may also hamper daily functioning

and the ability and energy to engage in meaningful activities, which are likely to affect overall life satisfaction and feelings of being socially connected. While it is less likely that

sleep disruption from technology use plays a key role in the aetiology of severe mental disorders requiring prolonged clinical intervention, we hypothesise that the general mental wellbeing

such as stress perceptions, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and feelings of social isolation may be affected. In a prior study using data from a population-based citizen science

sample of 24,856 Danish adults, we showed that 81 percent of the men and 88 percent of the women aged 16–25 years reported to use their smartphone before falling asleep a few times a week or

more, and one-third reported to use their smartphone during the sleep period5. We also showed that phone use during the sleep period relative to other smartphone behaviours had the

strongest association with poor sleep, and hence this behaviour might pose a risk factor for poor mental health. A systematic review shows that nighttime phone use is related to measures of

poor sleep8. However, most studies in the area are conducted among children and adolescents, and only a few studies have investigated nighttime smartphone use in relation to mental health in

adult populations6,23. We have only been able to identify one study that reported on the longitudinal relationship between nighttime smartphone use and mental health in an adult population,

and this study found no associations at follow-up6. Further, studies in the field are predominately based on self-reported measures of both nighttime smartphone use and mental health in

cross-sectional studies limiting the validity of these findings. Hence, more research is needed to investigate the relationship between nighttime smartphone use and mental health in adult

populations—in particular among young adults where nighttime smartphone use is very frequent5,24. In order to overcome measurement bias due to self-reports, phone tracking has been proposed

as an alternative strategy, but this approach has mostly been applied in small samples (N ~ 100) and with a short observation period25,26. Although this measurement method is difficult to

apply in large population-based studies, it has the advantage of being recorded independently from outcome(s) of interest with a very high information resolution. The aim of this paper is to

investigate whether nighttime smartphone use is associated with the risk of poor mental health and wellbeing, i.e. loneliness, depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and low life

satisfaction. We will use a unique dataset that allows us to study multiple behavioural dimensions of nighttime smartphone use in relation to mental health using longitudinal

high-dimensional tracking data from smartphones in a sample of 815 young adults. MATERIAL AND METHODS THE COPENHAGEN NETWORK STUDY In 2013, 3329 undergraduate students at the Danish

Technical University were invited to participate in the Copenhagen Network Study27. In total, 979 students (29%) accepted the invitation (60% were freshmen students). All participants signed

an informed consent. The students participating in the study were given a smartphone (LG Nexus 4) which was running customised software continuously recording information on all call and

text message interactions (not content). The students were required to insert their private SIM-card into the provided smartphone to make it their primary phone and to respond to a baseline

questionnaire. The questionnaire was presented using a custom-built web application. Facebook data (Facebook friends, likes, and status updates) were captured by asking the participants to

authorise data collection from their Facebook account using access tokens. All data were linked at the individual level, and we used data collected in a four-week period starting one week

after the participants first activated their smartphone. We excluded the first week of phone use to allow for adjustment to the new phone. As we assumed the sleep patterns over the weekends

to be considerably different from weekdays, we only used data from weekdays (Monday through Thursday) from the four-week period. We excluded individuals with no information on mental health

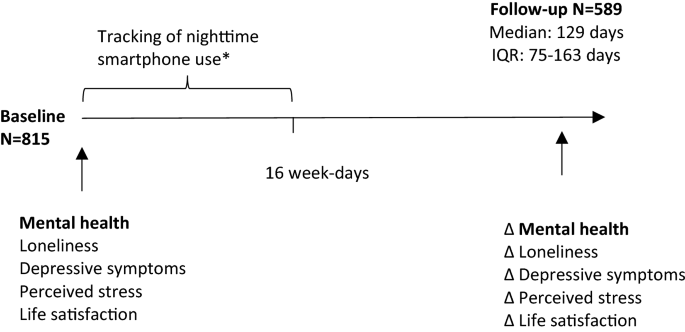

(N = 59) and with missing phone recordings (N = 105) yielding a total sample of 815 individuals who were included in the analyses at baseline. After approximately four months (interquartile

range (IQR): 75–163 days), 589 participants (72% of baseline population) responded to a follow-up questionnaire and of these between 47–51 participants had missing values in the four

outcomes of interests. More men (30%) than women (22%) were lost to follow-up, but loss to follow-up was unrelated to nighttime smartphone use, mental health, and age28. See Fig. 1 for an

overview of the study design. The experiments done in this study are in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. (Approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency, number:

2012–41-0664). The current study does not require approval by the National Committee on Health Research Ethics by Danish law. TRACKED NIGHTTIME SMARTPHONE USE: NUMBER OF NIGHTS WITH LESS

THAN SIX HOURS OF CONSECUTIVE SLEEP We recorded the exact timing of smartphone activities from one hour before self-reported usual weekday bedtime throughout the self-reported sleep period

calculated from self-reported usual weekday bedtimes and rise times. We recorded each of the following smartphone activities during the self-reported sleep period which all required active

engagement and thus indicating that the participant was awake: received ingoing calls, outgoing calls, outgoing text messages, uploaded Facebook status-reports and ‘liking’ a post on

Facebook. Building on this information including more than 250,000 records of nightly smartphone activity, we determined for each night the longest consecutive passive period without

smartphone activity within the self-reported sleep period. As it is well established in the literature that less than six hours of sleep is related to higher risk of morbidity and

mortality29, we derived a variable counting the number of nights out of the 16 week days where participants had less than six consecutive hours due to smartphone activity during the

self-reported sleep period. The variable was grouped into categories indicating the number of nights with less than six consecutive hours of no smartphone activity: 0 Nights, 1–3 Nights,

> 3 Nights. MENTAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING OUTCOMES _Loneliness_ was evaluated with a Danish version of the UCLA loneliness scale; a 20-item inventory measuring individual’s subjective

feelings of loneliness and social isolation. A score between 0 (least lonely) to 60 (most lonely) was obtained30. _Depressive symptoms_ were measured using the Major Depression Inventory

(MDI)31, which is a self-reported 12-item mood questionnaire evaluating depressive symptoms on a 5 point Likert scale. The total depressive symptoms severity scale ranges from 0 to 50, where

a score of 50 indicates the most severe level of depressive symptoms. _Perceived stress_ was measured using a Danish consensus translation of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)32. The 10-item

PSS instrument was designed to measure the degree to which everyday situations are appraised as being stressful measured using a score ranging from 0 to 40, where a score of 40 indicates

the highest level of perceived stress. The Danish consensus translation of the PSS has shown good reliability, internal consistency (ICC = 0.87, Cronbach’s alfa = 0.84) and validity33. _Life

Satisfaction_ was evaluated with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS): This 5-item inventory measures global satisfaction with one's life. Scores range from 5 (lowest life

satisfaction) to 25 (highest life satisfaction)34. To increase ease of interpretation and comparability between outcomes, all measures were re-scaled from their original scale to a scale

going from 0 to ten. CO-VARIATES _Gender, age_ and _cohabitation_ (Do you live alone; yes, no) were self-reported in the baseline questionnaire. The personality traits _neuroticism and

extroversion_ were measured at baseline with the 44-item version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI)35. These traits are strongly related to both smartphone use and mental health35,36. _The

social network score_ was measured at baseline with the following item from the Copenhagen Social Relations Questionnaire37 indicating a social contact frequency with six different social

roles: How often are you together with any of the following people who you do not live with? Mother, father, siblings, extended family, partner, and friends (Response code: Several days a

week; About once a week; One to three times a month; Less often than once a month; Never; Have no; Live with). Participants reporting “live with” were grouped in the highest contact

frequency category, and participants reporting “Have no” were grouped in the lowest contact frequency group. The contact frequency from the six roles was summed to indicate a measure of

total contact frequency and hence reflect both diversity and frequency in social interactions. The social network is strongly related to mental health38 and smartphone use as smartphone use

may reflect interaction with an underlying social network39. ANALYTICAL STRATEGY First, we explored characteristics of the study population. Second, we conducted two separate cross-sectional

multiple linear regression analyses for the associations between the nighttime smartphone use and the four mental health outcomes at baseline in the full population (N = 815) and at

follow-up (NUCLA = 542, NMDI = 538, NPSS = 540, NSWLS = 541). The analyses were adjusted for age, gender, cohabitation status, social network score, and the personality traits neuroticism

and extroversion which were identified as potential confounders based on the framework of directed acyclic graphs40. Third, we assessed the associations between nighttime smartphone use and

changes in the four mental health outcomes from baseline to follow-up approximately four months later by including the baseline mental health outcomes in addition to the identified

confounders in a follow-up model. F-tests and associated _p_-values were calculated for the final models evaluating the significance of nighttime smartphone use and the considered mental

health outcome. In a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the baseline models to the population at follow-up to evaluate whether the observed changes were due to effects of underlying

different populations. In addition, we included an interaction term between the variable of nighttime smartphone use and follow-up time (grouped in three time-bands: less than 75 days,

between 750 and 150 days, and above 150 days) in order to assess whether the effect of nighttime smartphone use differed between participants with short and long follow-up time. All analyses

were conducted in the statistical software R. ETHICAL APPROVAL Data used in the manuscript are from the Copenhagen Networks study which has been approved by the Danish Data Protection

Agency (DDPA) Journal nr 2012–41- 0664. DDPA is the relevant legal entity in Denmark. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION Table 1 shows the summary statistics for the study population at baseline. The mean age was 21.6 years and the majority of the study population was

men (77.3%), which roughly corresponded to the gender and age distribution at the Danish Technical University (men: 68%, mean age: 21). Participants who had more than three nights with less

than 6 h of consecutive sleep due to smartphone use were more often women and on average scored higher on the extroversion personality dimension compared to participants with a lower number

of nights with smartphone use. NIGHTTIME SMARTPHONE USE AND MENTAL HEALTH Figure 2 shows the baseline associations between nighttime smartphone use and mental health outcomes. The figure

shows that having nights with less than six hours of consecutive sleep is associated with higher levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms. We found that participants having 1–3

nights with smartphone use had on average a 0.25 points higher score (95%CI:0.08;0.41) on the PSS scale from 0 to 10, and a 0.33 (95%CI: 0.06;0.60) points higher score on the MDI scale

ranging from 0 to 10 compared to participants with no smartphone interrupted nights. The results were less clear for loneliness and life satisfaction, but nighttime smartphone use appeared

to be associated with a lower level of loneliness—participants having > 3 nights with nighttime smartphone use scored on average 0.30 lower (mean diff. − 0.30 95%CI: − 0.61; − 0.001) on

the UCLA loneliness scale ranging from 0 to 10 than participants not using their phone during the sleep period. All mentioned estimates were adjusted for potential confounders. Figure 3

shows the associations between nighttime smartphone use and changes in mental health outcomes at follow-up. Overall, there were no clear associations between smartphone interrupted sleep and

changes in perceived stress, loneliness and life satisfaction over an average four-month follow-up period. Contrary to our hypothesis, more than three nights of nighttime smartphone use was

associated with a small decrease in depressive symptoms from baseline to follow-up compared with participants who did not use the smartphone at night. The number of participants in this

group was small (N = 45), and hence this result should be interpreted with caution. Limiting the baseline associations to participants who responded to the follow-up questionnaire did not

change the results considerably, and the observed effects did not differ by length of follow-up. See supplementary information for a full table of all estimates and results from sensitivity

analyses. DISCUSSION In a longitudinal study of 815 young adults, we leveraged objective tracking data from more than 250,000 data points, and we found that nighttime smartphone use was

associated with slightly higher levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms at baseline. These differences were small and could not be replicated in longitudinal analyses. Rather, it

appeared that frequent nighttime smartphone use was associated with a small decrease in depressive symptoms over time. An Australian cross-sectional survey of 397 adults showed that sending

and receiving calls and texts after lights out and being woken by phone use were associated with lowered mood23. Likewise, a Swedish study of 4156 young adults (age: 20–24 years) found

associations between self-reported nighttime awakenings by the phone and perceived stress and depressive symptoms. However, the study did not find longitudinal associations between these

variables at follow-up one year later6. Although conducted among adolescents (1101 adolescents aged 13–16 years), another Australian study is worth mentioning as it is one of few studies

considering changes in mental health similar to the current study. They found cross-sectional associations between nighttime smartphone use and depressive symptoms, but when they considered

changes in nighttime smartphone use and subsequent changes in depressive symptoms, this relationship was attenuated41. Although the present study was carried out using a different

measurement method of nighttime smartphone use, we report similar findings. In an earlier cross-sectional study also using objective tracking data, we found that nighttime smartphone use was

not associated with depressive symptoms24. Combined, these findings do not support the prevailing hypothesis that nighttime smartphone use is a strong risk factor for poor mental health

among adults, and they underpin the complexity of teasing out causal inference in the area of nightly smartphone use, sleep and mental health as these factors are highly interlinked. In the

same vein, it is important to keep in mind that the type of activity considered in the current study indicated social interaction. It is well known that social relations and social

interactions are generally beneficial to mental health38. The current study population consisted of young adults newly enrolled at university where forming social networks and engaging in

social interaction are crucial for mental health and wellbeing. Even though nighttime smartphone use is likely to disturb sleep, it is possible that the beneficial effects from having social

contact overrides the negative consequences of having disturbed sleep. We tried to accommodate this dual effect by adjusting for participants’ social network score at baseline, but may not

fully capture this social element. An American cross-sectional survey conducted among 308 frequent smartphone users suggested that anxiety was related to consumption-based smartphone use

(e.g., news consumption, entertainment, relaxation) rather than social smartphone use42. This highlights the importance of considering the type and content of smartphone activity as

different activities with potentially different implications for mental health. We suggest future studies to consider a broader range of nighttime smartphone activities (screen use, passive

usage, active usage) in order to investigate the mental health effects of smartphone activities. STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES We were able to objectively track the nighttime smartphone use of

more than 800 young adults and relate this behaviour to changes in several validated mental health outcomes. This is a particular advantage as most previous studies using tracking data in

combination with survey data have only included relatively small samples in a cross-sectional set-up25,26. We aimed at only considering smartphone activities that indicated that the

participant was awake during their self-reported sleep period, e.g. only _received_ incoming calls and not just incoming calls. Still, it is difficult to know whether the participants had

sleep interruptions due to the incoming call or whether they were already awake because of existing sleep problems that may have affected the mental health status prior to the study. In an

earlier study conducted in the same study population (restricted to first-year students), we found that mental health was important for daily smartphone communication and social

interaction43. In the current study, we tried to accommodate the potential reversed causation by considering changes in mental health occurring after baseline. The small differences in

mental health detected at baseline could suggest that reverse causality mechanisms may be a valid explanation. Further, it should be mentioned that it was not possible to consider all

relevant activities carried out using the phone, and the recorded nightly smartphone activity is likely to be underestimated. We prioritized recording activities from the most commonly used

social media platform among young adults in Denmark during the study period 2013–1444. In relation to this, it should be noted that the exposure group having most nights with smartphone use

(> 3 nights) only consisted of 45 participants and hence, results from this group should be interpreted with caution. Further, it should be noted that we did not have information on the

participants’ bedtimes during weekends and we could therefore only consider sleep disruptions during weekdays. The observed effects could potentially differ between men and women. Due to the

low proportion of women in this population, we refrained from investigating stratified gender effects, but we suggest future studies to explore this aspect further. CONCLUSIONS Contrary to

the prevailing hypothesis, nighttime smartphone use was not strongly associated with poor mental health, possibly because smartphone use is also a social phenomenon with beneficial effects

on mental health. Further research is warranted in order to confirm these findings preferably designs distinguishing between nightly social and consumption-related smartphone use. DATA

AVAILABILITY The full data set contains personally identifiable telecommunication patterns and survey data. According to the Act on Processing of Personal Data, such data cannot be made

available in the public domain. The authors confirm that the data is available upon request to all interested researchers under conditions stipulated by the DDPA. Data inquiries should be

addressed to the Social Fabric steering committee (http:// sodas.ku.dk), to be reached at [email protected]. REFERENCES * Rehm, J. & Shield, K. D. Global burden of disease and the impact of

mental and addictive disorders. _Curr. Psychiatry Rep._ 21(2), 10 (2019). Article Google Scholar * McManus, S. & Gunnell, D. Trends in mental health, non-suicidal self-harm and

suicide attempts in 16–24-year old students and non-students in England, 2000–2014. _Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol._ 55(1), 125–128 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Sundhedsstyrelsen, _Danskernes Sundhed - Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017_. 2018: Sundhedsstyrelsen. * Pew Research Center. _Mobile Fact Sheet 2021_. 2021; Available from:

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. * Dissing, A. S. _et al._ Daytime and nighttime smartphone use A study of associations between multidimensional smartphone behaviours

and sleep among 24856 Danish adults. _J. Sleep Res_ 30(6), e13356 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Thomée, S., Härenstam, A. & Hagberg, M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep

disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults - a prospective cohort study. _BMC Public Health_ 11, 66 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Vahedi, Z. & Saiphoo, A. The

association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. _Stress. Health_ 34(3), 347–358 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Thomée, S. Mobile phone use and mental

health. A review of the research that takes a psychological perspective on exposure. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health._ 15(12), 2692 (2018). Article Google Scholar * The United

Nations. _Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages_. 2021; Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/. *

He, J.-W. _et al._ Effect of restricting bedtime mobile phone use on sleep, arousal, mood, and working memory: A randomized pilot trial. _PLoS ONE_ 15(2), e0228756 (2020). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Cain, N. & Gradisar, M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. _Sleep Med._ 11(8), 735–742 (2010). Article Google Scholar *

Zisapel, N. New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. _Br. J. Pharmacol._ 175(16), 3190–3199 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Tang, N. K. & Harvey, A. G. Effects of cognitive arousal and physiological arousal on sleep perception. _Sleep_ 27(1), 69–78 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Chang, A.-M. _et al._

Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 112(4), 1232–1237 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Marshall, N. S. & Stranges, S. _Sleep duration: Risk factor or risk marker for ill-health_ 35–49 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010). Google Scholar * Lockley, S.W.,

_Principles of sleep-wake regulation_. 10–21 (2018) * Walker, M. P. & van Der Helm, E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. _Psychol. Bull._ 135(5), 731

(2009). Article Google Scholar * Harvey, A. G. _et al._ Sleep disturbance as transdiagnostic: consideration of neurobiological mechanisms. _Clin. Psychol. Rev._ 31(2), 225–235 (2011).

Article Google Scholar * Riemann, D., Berger, M. & Voderholzer, U. Sleep and depression — results from psychobiological studies: an overview. _Biol. Psychol._ 57(1), 67–103 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Freeman, D. _et al._ The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): a randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. _The Lancet Psychiatry_

4(10), 749–758 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Becker, N. B. _et al._ Sleep quality and stress: a literature review. In _Advanced research in health, education and social sciences_ (eds

Marius, M. _et al._) 53–61 (Editora Universitária, Santiago, 2015). Google Scholar * Yang, L. _et al._ The effects of psychological stress on depression. _Curr. Neuropharmacol._ 13(4),

494–504 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Saling, L. L. & Haire, M. Are you awake? Mobile phone use after lights out. _Comput. Hum. Behav._ 64, 932–937 (2016). Article Google

Scholar * Rod, N. H. _et al._ Overnight smartphone use: A new public health challenge? A novel study design based on high-resolution smartphone data. _PLoS ONE_ 13(10), e0204811 (2018).

Article Google Scholar * Rozgonjuk, D. _et al._ The association between problematic smartphone use, depression and anxiety symptom severity, and objectively measured smartphone use over

one week. _Comput. Hum. Behav._ 87, 10–17 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Elhai, J. D. _et al._ Depression and emotion regulation predict objective smartphone use measured over one week.

_Personality Individ. Differ._ 133, 21–28 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Stopczynski, A. _et al._ Measuring large-scale social networks with high resolution. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e95978 (2014).

Article ADS Google Scholar * Dissing, A. S. _et al._ Smartphone interactions and mental well-being in young adults: A longitudinal study based on objective high-resolution smartphone

data. _Scand. J. Public Health._ 49(3), 325–332 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Watson, N. F. _et al._ Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep

Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. _Sleep_ 38(8), 1161–1183 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Lasgaard, M. Reliability and

validity of the Danish version of the UCLA loneliness scale. _Personality Individ. Differ._ 42(7), 1359–1366 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Bech, P. _et al._ The sensitivity and

specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. _J. Affect. Disord._ 66(2), 159–164 (2001). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. _J. Health Soc. Behav._ 24(4), 385–396 (1983). Article CAS Google Scholar * Eskildsen, A. _et

al._ Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish consensus version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. _Scand. J. Work Environ. Health_ 41(5), 486–490 (2015). Article Google

Scholar * Diener, E. _et al._ The satisfaction with life scale. _J. Pers. Assess._ 49(1), 71–75 (1985). Article CAS Google Scholar * John, O. P., Naumann, L. P. & Soto, C. J.

Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In _Handbook of personality: Theory and research_ (eds John, O. P. _et al._) 114–158

(Guilford Press, 2008). Google Scholar * De-Sola Gutiérrez, J., Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. & Rubio, G. Cell-phone addiction: a review. _Front. Psyc._ 7, 175 (2016). Google Scholar *

Lund, R. _et al._ Content validity and reliability of the copenhagen social relations questionnaire. _J. Aging Health_ 26(1), 128–150 (2014). Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Kawachi,

I. & Berkman, L. F. Social ties and mental health. _J. Urban Health_ 78(3), 458–467 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Dissing, A. S. _et al._ Measuring social integration and tie

strength with smartphone and survey data. _PLoS ONE_ 13(8), e0200678 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Greenland, S. & Pearl, J. Causal Diagrams. In _Modern Epidemiology_ 183–209

(Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, UK, 2008). Google Scholar * Vernon, L., Modecki, K. L. & Barber, B. L. Mobile phones in the bedroom: Trajectories of sleep habits and subsequent

adolescent psychosocial development. _Child Dev._ 89(1), 66–77 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Elhai, J. D. _et al._ Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression,

anxiety and problematic smartphone use. _Comput. Hum. Behav._ 69, 75–82 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Dissing, A. S. _et al._ High perceived stress and social interaction behaviour

among young adults A study based on objective measures of face-to-face and smartphone interactions. _PLoS ONE_ 14(7), 0218429 (2019). Article Google Scholar * STATISTA. _Share of social

media users in Denmark from 2016 to 2020, by social media site_. 2021; Available from:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/861527/share-of-social-media-users-in-denmark-by-social-media-site/. Download references FUNDING The project was supported by funds from the Danish

Research Council (grant no. 7025-00005B), the Health Foundation (Helsefonden, grant no. 20-B-0254), and the Velliv Association (Velliv Foreningen, grant no. 20–0047). The Copenhagen Social

Network Study was made possible by an interdisciplinary University of Copenhagen 2016 grant, Social Fabric (PI David Dreyer Lassen, co-PI Sune Lehman). This grant has funded purchase of the

smartphones, as well as technical personnel. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. AUTHOR INFORMATION

AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Section of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Oester Farimagsgade 5, Postbox 2099, 1014, Copenhagen, Denmark Agnete Skovlund

Dissing, Thea Otte Andersen & Naja Hulvej Rod * Section of Biostatistics, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Oester Farimagsgade 5, Postbox 2099, 1014, Copenhagen,

Denmark Andreas Kryger Jensen * Section of Social Medicine, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Oester Farimagsgade 5, Postbox 2099, 1014, Copenhagen, Denmark Rikke Lund *

Center for Healthy Ageing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Blegdamsvej 3B, 2200, Copenhagen, Denmark Rikke Lund Authors * Agnete Skovlund Dissing View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thea Otte Andersen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andreas

Kryger Jensen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rikke Lund View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Naja Hulvej Rod View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Obtained funding: A.S.D., T.O.A., N.H.R. Collected data: A.S.D.,

R.L., N.H.R. Conceptual framing of the manuscript: A.S.D., T.O.A., A.K.J., R.L., N.H.R. Conducted analyses: A.S.D. Manuscript writing: A.S.D. Supervision: R.L., N.H.R., A.K.J. All authors

reviewed and approved the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Agnete Skovlund Dissing. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit

line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use,

you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Dissing, A.S., Andersen, T.O., Jensen, A.K. _et al._ Nighttime smartphone use and changes in mental health and wellbeing among young adults: a longitudinal study

based on high-resolution tracking data. _Sci Rep_ 12, 8013 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10116-z Download citation * Received: 13 July 2021 * Accepted: 04 March 2022 *

Published: 15 May 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10116-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative