Efficacy of escitalopram for poststroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Depression is very common after stroke, causing multiple sequelae. We aimed to explore the efficacy of escitalopram for poststroke depression (PSD). PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane

Central Register of Controlled Trials, Clinical trials. gov, Wan fang Data (Chinese), VIP (Chinese) and CNKI (Chinese) were retrieved from inception to May 2021. We recruited Randomized

Controlled Trials (RCTs) which met the inclusion criteria in our study. The depression rating scores, the incidence of PSD, adverse events as well as functional outcomes were analyzed. 11

studies and 1374 participants were recruited in our work. The results were depicted: the reduction of depression rating scores was significant in the escitalopram groups and the standard

mean difference (SMD) was − 1.25 (_P_ < 0.001), 95% confidence interval (95% CI), − 1.82 to − 0.68; the risk ratio (RR) of the incidence of PSD was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.29 to 0.91; _P_ = 0.007

< 0.05), which was significantly lower in the escitalopram groups; Escitalopram is safe for stroke patients; there was improvement of the motor function. However, in sensitivity

analyses, the conclusions of the motor function and the incidence of drowsiness were altered. The study suggests that escitalopram has a potentially effective role compared with control

groups and demonstrates escitalopram is safe. However, the results of the motor function and the incidence of drowsiness should be considered carefully and remain to be discussed in the

future. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ENHANCED EVIDENCE-BASED CARE FOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS: A META-ANALYSIS OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS Article Open access

16 October 2021 A META-ANALYSIS OF THE EFFECTS OF KETAMINE ON SUICIDAL IDEATION IN DEPRESSION PATIENTS Article Open access 10 June 2024 PREVALENCE, AWARENESS, AND TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION

AMONG COMMUNITY-DWELLING STROKE SURVIVORS IN KOREA Article Open access 08 March 2022 INTRODUCTION Approximately 79,5000 people suffer a new or recurrent stroke each year1. Additionally, an

epidemiology meta-analysis revealed 31% of patients developed depression during 5 years following stroke2. Frustratingly, poststroke depression (PSD) could impair the cognitive level and

activities of daily living (ADL), cause negative sequelae on the recovery of patients, and increase the burden of caregivers3. So far, the etiological mechanisms of PSD have not been

revealed clearly. Psychological, social, and biological factors contributed to PSD together4,5. Stroke survivors with the homozygous short variation allele genotype of the serotonin

transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) have a higher risk of PSD6. Both stroke and depression are associated with increased inflammation7. Antidepressants can lower the levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines8. These new promising methods show that, in terms of the physical consequences of stroke, these drugs can reduce bad mood9. Escitalopram is a selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with few drug interactions, and is thus suitable for stroke patients who are prescribed multiple medications10. In recent years, SSRI escitalopram has been proved

to be effective for the treatment and prevention of PSD, but there are still controversy11,12. It demonstrates that escitalopram is safe in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) for prevention

of PSD, and decreases effectively the incidence of PSD, as well as improving ADL and social function11. Moreover, it also shows that there are no significant differences on cognitive

function compared with problem-solving therapy (PST) and placebo. However, a study of escitalopram by Kim et al.12 shows that the occurrence of moderate or severe depressive symptoms and

adverse events are not statistically significant except diarrhea, ADL improvement, cognitive function, motor function and neurological defects. Two SSRI systematic reviews13,14 enrolled RCTs

of escitalopram have been found, to our knowledge, which both only included a study of Robinson et al.11. Recently, new RCTs of escitalopram are pouring out15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, which

were conducted in different circumstances, and the integration effects of these studies was vague. Therefore, we aimed at conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs about

escitalopram arm compared with the placebo/the blank control arm, evaluating the depression rating scores, the occurrence of depression along with depressive symptoms, the frequency of

adverse events and other significant clinical outcomes. METHODS SEARCH STRATEGY AND STUDY SELECTION 8 databases were searched (search strategy in online supplemental data), Medline via

PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Clinical Trials.gov, CNKI (Chinese), Wan fang (Chinese), and VIP database (Chinese), from inception to May 2021. In

addition, we scrutinized references of relevant papers and also contacted with authors to get the detailed data if necessary. Inclusion criteria: ① RCTs were enrolled for participants with a

clinical diagnosis of stroke; ② The experimental group was treated with escitalopram at any dose, by any mode of delivery and the control arm was included a placebo or the blank control; ③

The primary outcomes: depression rating scores, in which the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) was preferred, the incidence of PSD, and adverse events including gastrointestinal side effects,

sexual side events, cardiovascular adverse effects, and other adverse events. The secondary outcomes: neurological deficit scores, ADL, cognitive impairments, and motor function. For

functional outcomes, we gave preference to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), the Barthel Index (BI), Fugl—Meyer motor scale (FM), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Exclusion criteria: ① The type of study was a non-randomized controlled study; ② The subjects were not stroke patients or no clear diagnostic

criteria; ③ The experimental group was not treated with escitalopram, or the control arm was not included a placebo or the blank control, or drugs and therapies with mixed effects; ④ Outcome

indicators were not required in this study; ⑤ Intervention methods were not expressed clearly and could not be verified by the authors. Two team members exacted data of each literature

independently. A third investigator was discussed with if necessary. QUALITY ASSESSMENT Study quality was independently assessed by two reviewers based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk

of bias tool including randomization, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. An opinion was sought from a third reviewer if the first two

reviewers could not reach an agreement. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Pooled analyses were carried out at any follow-up point by RevMan 5.3 software (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center, The

Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was described by categorical data. Standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was used for continuous

outcomes. _P_ < 0.05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance. Statistical heterogeneity of trials was evaluated by I224. We used a random-effect model to calculate the pooled

estimates if we observed I2 > 50% or _P_ < 0.10, and on the contrary, we used a fixed-effect model. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on different rating scales, depression or not

at recruitment and follow-up duration (< 3 months vs 3 ~ 6 months vs > 6 months). In sensitivity analyses, the trails with high heterogeneity were excluded. Publication bias was

assessed by a funnel plot and Egger statistical test that was carried out by Stata 12.0 and _P_ < 0.10 was considered as statistically asymmetry25. Our study was conducted according to

the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. We analyzed the data about previous studies which were published early in our research, so ethical approval and patient consent were not necessary and therefore

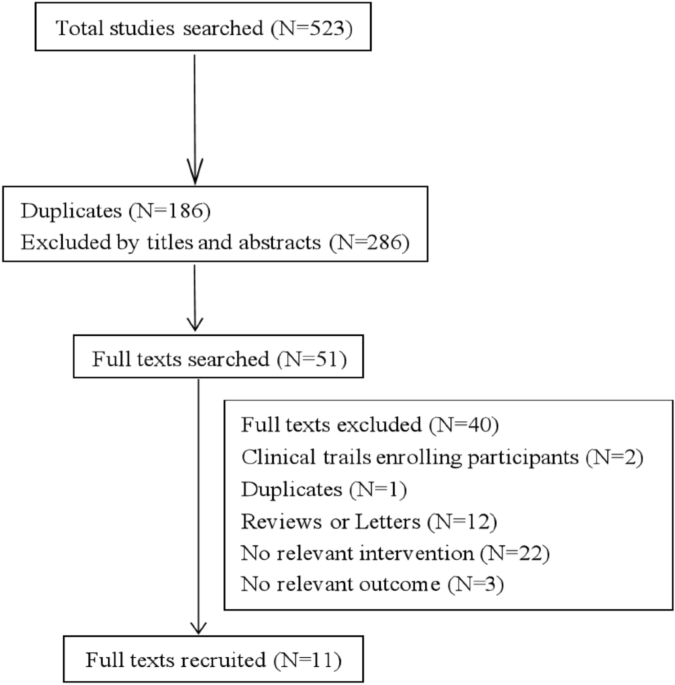

not provided. RESULTS STUDY SELECTION AND CHARACTERISTICS We searched 5 English databases (27 from Medline via PubMed, 72 from Embase, 123 from Scopus, 12 from Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials, 3 from Clinical Trials.gov) and 3 Chinese databases (100 from CNKI, 99 from Wan fang, 87 from VIP database) from inception to May 2021. After removing duplicates, there

existed 285 records and 51 full texts were obtained. Finally, 11 articles were recruited (Fig. 1), in which 1374 participants were randomly enrolled in the escitalopram or the

control11,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Most of the papers excluded the participants with severe comprehension deficits, aphasia, and unstable medical conditions. The follow-up was at

treatment end in 9 RCTs11,12,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. There were 2 RCTs of which the follow-up duration was beyond treatment end12,16, however, we could not obtain the detailed data of Kim

et al.12 at 6 months and Mikami et al.16 at 18 months. Participants suffered from depression at recruitment in 5 papers12,19,20,22,23. In 6 papers, participants were with no diagnosis of

depression at recruitment11,15,16,17,18,21. Table 1 shows the detailed characteristics of each paper. DEPRESSION RATING SCORES Figure 2 shows that the SMD of depression rating scores was −

1.25 (95% CI, − 1.82 to − 0.68; 7 trials; I2 = 90%) among participants allocated escitalopram compared with control. But there was moderate heterogeneity among participants who were with

depression (SMD = -1.32; 95% CI, − 1.74 to − 0.90; I2 = 57%) or not depression (SMD = -1.15; 95% CI, − 2.21 to − 0.09; I2 = 95%) at recruitment and with no heterogeneity between subgroups

(I2 = 0%; _P_ = 0.77). It was reported that the antidepressant efficiency was obvious statistical significance (_P_ < 0.05) in escitalopram group (88.9%) compared with the control (64.7%)

in one trail, but we could not obtain the detailed scores23. Figure 3 shows that there was obvious statistical significance in the subgroup where follow-up duration was the group of < 3

months (SMD = -1.78; 95% CI, − 2.78 to − 0.77; I2 = 91%) and the group of 3 ~ 6 months (SMD = -1.23; 95% CI, − 1.50 to − 0.97; I2 = 0%), however, there were no advantage of escitalopram in

the subgroups, follow-up duration ≥ 6 months, but only one trial was included_._ Significant heterogeneity was among subgroups (I2 = 93.1%; _P_ < 0.001). THE INCIDENCE OF POSTSTROKE

DEPRESSION The incidence of PSD was higher in control compared with escitalopram and with moderate heterogeneity (RR = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.91; 5 trials; I2 = 72%; Fig. 4). SAFETY No

statistical significance was between escitalopram and control among trials for gastrointestinal side events. For nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain and constipation, the RR was 1.31 (95% CI,

0.86 to 1.99; 7 trials; Fig. 5) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 59%, _P_ = 0.02) among trials. There was also no statistical significance for other gastrointestinal side events: the dry

mouth (RR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52 to 1.03; 3 trials; I2 = 46%; Supplemental Fig. 1), the anorexia (RR = 1.66; 95% CI, 0.95 to 2.90; 3 trials; I2 = 2%; Supplemental Fig. 2), the indigestion (RR

= 1.26; 95% CI, 0.75 to 2.11; 3 trials; I2 = 0%; Supplemental Fig. 3), the bleeding (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.15 to 7.07; 2 trials; I2 = 0%; Supplemental Fig. 4). There was no significant

cardiovascular adverse effects in escitalopram groups. The RR was 1.14 (95% CI, 0.44 to 2.96; 3 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.65; Fig. 6) for palpitation. For tachycardia, the RR was 1.07 (95%

CI, 0.90 to 1.28; 2 trials; Supplemental Fig. 5) without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; _P_ = 0.65) among trials. Only 2 trails reported the chest pain, and the RR was 1.35 (95% CI, 0.68 to 2.70; 2

trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.57; Supplemental Fig. 6). Escitalopram did not affect sexual function versus control (RR = 1.39; 95% CI, 0.94 2.05; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.72; 3 trials; Fig. 7) among

trials for sexual side events. The escitalopram was safe for the other adverse events, except for the drowsiness (RR = 6.95; 95% CI, 1.61 to 30.09; 3 trials; I2 = 31%, _P_ = 0.23;

Supplemental Fig. 7), and there was no or low heterogeneity among all enrolled trials: the insomnia (RR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.48 to 1.39; 4 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.71; Supplemental Fig. 8), the

dizziness (RR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.32; 3 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.95; Supplemental Fig. 9), the fatigue (RR = 1.25; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.74; 3 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.73; Supplemental

Fig. 10), the increased sweating (RR = 1.78; 95% CI, 0.99 to 3.20; 3 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ = 0.80; Supplemental Fig. 11), the falls (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.15 to 7.07; 2 trials; I2 = 0%, _P_ =

0.97; Supplemental Fig. 12), the pain (RR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.48 to 1.63; 2 trials; I2 = 24%, _P_ = 0.25; Supplemental Fig. 13), the dysuria (RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.51 to 3.77; 2 trials; I2 =

0%, _P_ = 0.85; Supplemental Fig. 14), the anxiety (RR = 1.98; 95% CI, 0.37 to 10.61; 2 trials; I2 = 48%, _P_ = 0.16; Supplemental Fig. 15). It was no statistical significance (_P_ >

0.05) in escitalopram group compared with the control, including the incidence of the paraesthesia, tremor, pruritus and peripheral oedema, however, they were only reported in one trail12.

NEUROLOGICAL DEFICIT SCORES The SMD was − 0.97 (95% CI, − 1.97 to 0.03; 4 trials; Supplemental Fig. 16) with high heterogeneity among trials (I2 = 97%), regarding different scales NFI

(Neurologic Function Impairment) (SMD = -3.25; 95% CI, − 3.86 to − 2.64) vs NIHSS (SMD = -0.15; 95% CI, − 0.46 to 0.17; I2 = 91%, _P_ = 0.15) vs MESSS (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI, − 0.69 to −

0.01). It was reported that the recovery rate of neurological function was obvious statistical significance (_P_ < 0.05) in escitalopram group (86.1%) compared with the control (58.8%) in

one trail, but we could not obtain the detailed scores23. ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING The pooled analysis was not in favor of the escitalopram compared with the control (SMD = 0.42; 95% CI,

− 0.32 to 1.16; I2 = 94%; Supplemental Fig. 17). COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENTS The SMD was 0.56 (95% CI, − 0.23 to 1.34; 3 trials; Supplemental Fig. 18) with high heterogeneity among trials (I2 =

94%; _P_ < 0.001). MOTOR FUNCTION There was a better effect in the escitalopram versus the control (SMD = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.93; 4 trials, Supplemental Fig. 19) with high

heterogeneity among trials (I2 = 83%; _P_ = 0.0005), between different motor function scales FM (SMD = 0.65; 95% CI, 0.25 to 1.06; I2 = 54%, _P_ = 0.11) vs Hemispheric Stroke Scale (SMD =

0.00; 95% CI, − 0.18 to 0.18). QUALITY ASSESSMENT AND SENSITIVITY ANALYSES The quality of studies enrolled was shown in Fig. 8. In the sensitivity analyses, studies of the low quality were

eliminated19,20,22, and the conclusions of pooled analyses were robust, except for the motor function (SMD = 0.36; 95% CI, − 0.40 to 1.13; I2 = 90%, _P_ = 0.002) and the drowsiness (SMD =

4.70; 95% CI, 0.17 to 127.25; I2 = 64%, _P_ = 0.09). Moreover, the I2 was decreased from 94 to 79% in the pooled analysis of the ADL. The inverted funnel plot of visual examination

depression score (Fig. 9) was symmetrical. Moreover, the Egger tests showed that the outcome of depression rating scores (_t_ = -0.77; _P_ = 0.478 > 0.10) was not affected by publication

bias. DISCUSSION The systematic review and meta-analysis give an up-to-date and detailed description of the efficacy of escitalopram for PSD, in which 11 papers and 1374 participants were

enrolled. Excitingly, participants allocated to the escitalopram were more improved than the control, including depression rating scores, the incidence of PSD and motor function, but the

participants enrolled in the escitalopram group did not experience more improved in aspect of the ADL, neurological function and cognitive function. Furthermore, the participants in the

escitalopram groups did not suffer more adverse events compared with the control groups in our research, except for the drowsiness. However, in sensitivity analyses, the conclusions of motor

function and the drowsiness were not stable, which should be considered carefully. Our research reveals escitalopram reduces effectively the depression rating scores and the incidence of

PSD, which demonstrates the escitalopram is effective in the treatment and prevention of PSD. Escitalopram is safe for stroke patients in our meta-analysis. The pooled results show the

participants treated with escitalopram are well tolerated for adverse events, including the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, sexual and other adverse events but the drowsiness which only 2

trails were enrolled, however, the escitalopram groups did not experience more drowsiness in the sensitivity analyses, which is consistent with our previous meta-analysis26 and is different

from two previous meta-analyses13,27, due to different types of antidepressants enrolled in that researches, especially tricyclic antidepressants included in Xu et al.27. It is negative for

the functional indexes we analyzed except for the motor function. In the sensitivity analyses, only the result of motor function is altered. The conclusions of functional indexes are not

consistent with previous meta-analyses26,27,28, which maybe only ≤ 4 papers are enrolled in each functional index and the validity should be interpreted cautiously and proved in the future.

One of the potential weaknesses was the high heterogeneity among trials in our research, except for the incidence of PSD and adverse events. The possible reasons were analyzed. Firstly, it

may be small samples of most trials we enrolled and low quality of some trails, which may lead to high risk of bias and overestimation29. So in the sensitivity analyses, the I2 was decreased

from 94 to 79% in the pooled analysis of the ADL. Secondly, different rating scales were used in the studies included, and one study shows the occurrence of PSD is different by different

depression scales (HAM-D17 vs. HAM-D6)30, which proved different scales could lead to different outcomes and conclusions. It is testified in the subgroup analyses of neurological function

(Supplemental Fig. 16) and motor function (Supplemental Fig. 19). Thirdly, after removing the paper16, the I2 was decreased from 90 to 80% in the pooled analysis of the depression rating

scores, and the reason maybe the intervention duration (12 months) was obviously longer than other trails enrolled. Fourthly, after removing the trail12, heterogeneity (I2 = 22%, _P_ = 0.26)

decreased significantly in the pooled analysis of cognitive function, which maybe the weight of the trail was too large and the studies enrolled were too few. The main problems of the

serious cognitive impairment, aphasia, and the severe stroke about the participants were excluded in the studies recruited, therefore we could not know whether those patients could be

treated with escitalopram, which was also a limitation of our research. Another limitation was that the studies enrolled were too few in some pooled analyses and related original studies

should be conducted to clarify and testify the results. The strengths also existed in our study. An extensive search was conducted, including online papers, references and unpublished

trials, as well as a fairly wide range of important clinical results. Additionally, sufficient sensitivity analyses and enough subgroup analyses were performed to ensure the reliability and

robustness of the results. In the future, it should be necessary to develop more detailed and rigorous basic experiments on mechanisms and clinical trials to make a better choice for

clinicians and patients. CONCLUSIONS Taken together, our findings prompt escitalopram is safe and effective for PSD. However, the pooled analyses of the motor function and the incidence of

drowsiness should be explained cautiously. Moreover, limitations and inspirations are provided for further researches in our study. Therefore, more multicenter, larger sample, more rigorous

and more result indexes designed RCTs are needed to evaluate the protective role of escitalopram on PSD. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 06 APRIL 2022 A Correction to this paper has been published:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10039-9 _ REFERENCES * Mozaffarian, D. _et al._ Heart disease and stroke statistics–2016 update. _Circulation_ 133, e38–e360 (2016). PubMed Google Scholar

* Hackett, M. L. & Pickles, K. Part I: Frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. _Int. J. Stroke_ 9, 1017–1025

(2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ayerbe, L., Ayis, S., Wolfe, C. D. A. & Rudd, A. G. Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 202, 14–21 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * De Ryck, A. _et al._ Poststroke depression and its multifactorial nature: results from a prospective

longitudinal study. _J. Neurol. Sci._ 347, 159–166 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hackett, M. L., Yapa, C., Parag, V. & Anderson, C. S. Frequency of depression after stroke:

A systematic review of observational studies. _Stroke_ 36, 1330–13340 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mak, K. K., Kong, W. Y., Mak, A., Sharma, V. K. & Ho, R. C. Polymorphisms

of the serotonin transporter gene and post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis. _J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry_ 84, 322–328 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Geng, H. H. _et al._ The

relationship between c-reactive protein level and discharge outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 13, 636 (2016). Article PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Lu, Y. _et al._ Chronic administration of fluoxetine and pro-inflammatory cytokine change in a rat model of depression. _PLoS ONE_ 12(10), e0186700 (2017). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chollet, F. _et al._ Use of antidepressant medications to improve outcomes after stroke. _Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep._ 13, 318 (2013). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Puri, B. K., Ho, R., Hall, A. Revision Notes in Psychiatry; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA (2014). * Robinson, R. G. _et al._ Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy

for prevention of poststroke depression: A randomized controlled trial. _JAMA_ 299, 2391–2400 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kim, J. S. _et al._ Efficacy of

early administration of escitalopram on depressive and emotional symptoms and neurological dysfunction after stroke: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.

_Lancet Psychiatry_ 4, 33–41 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mead, G. E. _et al._ Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for stroke recovery: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. _Stroke_ 44, 844–850 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mead, G. E. _et al._ Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery (Review). _Cochrane

Database Syst. Rev._ 11, CD009286 (2012). PubMed Google Scholar * Jorge, R. E., Acion, L., Moser, D., Adams, H. P. & Robinson, R. G. Escitalopram and enhancement of cognitive recovery

following stroke. _Arch. Gen. Psychiatry_ 67(2), 187–196 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mikami, K. _et al._ Increased frequency of first-episode poststroke

depression after discontinuation of escitalopram. _Stroke_ 42, 3281–3283 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhan, Y. H. _et al._ Effect of escitalopram on motor

recovery after ischemic stroke. _Chin. Hosp. Pharm. J._ 34, 752–755 (2014). Google Scholar * Zhan, Y. H., Tong, S. J., An, X. K., Lu, C. X. & Ma, Q. L. Effect of escitalopram for

cognitive recovery after acute ischemic stroke. _Chin. Gen. Pract._ 17, 2422–2425 (2014). CAS Google Scholar * Wang, X. F. Randomized controlled trial of escitalopram on outpatients with

post-stroke depression. _China Pharmacist._ 15, 81–82 (2012). ADS Google Scholar * Jiang, D. D., Peng, C. & Lu, Y. C. Effect of escitalopram oxalate on motor recovery with post-stroke

depression. _Chin. Manipulat. Rehabilit. Med._ 6, 76–77 (2015). Google Scholar * Zhao, X. H., Wen, J. Z. & Yuan, F. Clinical observation of escitalopram oxalate for preventing

post-stroke depression. _Drugs Clin._ 29, 269–272 (2014). CAS Google Scholar * Li, X. Y., Zhang, Z. D. & Zhang, T. Effect of early antidepressant treatment on prognosis of patients

with post-stroke depression. _Shaanxi Med. J._ 45, 1344–1346 (2016). Google Scholar * Lin, L. Effect of escitalopram on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenergic axis function in patients with

post-stroke depression. _Chin. J. Pharmacoepidemiol._ 21, 417–419 (2012). ADS CAS Google Scholar * Higgins, J. P. T., Green, S.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. * Egger, M. & Smith, G. D. Meta-analysis: Bias in location and selection of studies. _BMJ_ 316, 61–66

(1998). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Feng, R. F. _et al._ Effect of sertraline in the treatment and prevention of poststroke depression: A meta-analysis.

_Medicine_ 97, e13453 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Xu, X. M. _et al._ Efficacy and feasibility of antidepressant treatment in patients with post-stroke

depression. _Medicine_ 95, e5349 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chen, Y., Guo, J. J., Zhan, S. & Patel, N. C. Treatment effects of antidepressants in

patients with post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis. _Ann. Pharmacother._ 40, 2115–2122 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wickenberg-Bolin, U., Goransson, H., Fryknas, M.,

Gustafsson, M. G. & Isaksson, A. Improved variance estimation of classification performance via reduction of bias caused by small sample size. _BMC Bioinf._ 7, 127–127 (2006). Article

Google Scholar * Rasmussen, A. _et al._ A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the prevention of depression in stroke patients. _Psychosomatics_ 44(3), 216–221 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Rong-fang Feng and Rui Ma collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. Li Guo, Peng Wang and Xu Ji

participated in writing of the manuscript. Rong-fang Feng, Rui Ma, Li Guo and Peng Wang conceived and designed this study. Zhen-xiang Zhang extracted the data and modified the paper.

Meng-meng Li and Jia-wei Jiao extracted the data. All authors reviewed the paper, read and approved the final manuscript. FUNDING This work is supported by the Innovative Talent Project of

Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (20HASTIT047), Philosophy and social science planning project of Henan (2021BSH017), Foundation of Co-constructing Project of Henan Province and

National Health Commission (SBGJ202002103), the Medical Education Research Project of Henan Health Commission (Wjlx2020362), Teaching program of Zhengzhou University (2021ZZUKCLX025,

2021ZZUJGLX194 and 2021-32), the Project of Social Science association in Henan Province (SKL-2021-472 and SKL-2021-476) and Zhengzhou (2021-0651), the Science and Technology Project of

Henan Science and Technology Department (202102310069 and 192102310531). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou,

450052, Henan, People’s Republic of China Rong-fang Feng & Li Guo * College of Physical Education (Based School), Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, Henan, People’s Republic of

China Rui Ma * Department of Basic Medicine, School of Nursing and Health, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, Henan, People’s Republic of China Peng Wang & Jia-wei Jiao * Zhengzhou

University of Industrial Technology, Zhengzhou, 450002, Henan, People’s Republic of China Peng Wang * Medical School of Huanghe Science and Technology University, Zhengzhou, 450006, Henan,

People’s Republic of China Peng Wang * Henan University of Chinese Medicine, Zhengzhou, 450046, Henan, People’s Republic of China Xu Ji * Department of Clinical Medicine, School of Nursing

and Health, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, Henan, People’s Republic of China Zhen-xiang Zhang * Zhengzhou Central Hospital Affiliated to Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450007,

People’s Republic of China Meng-meng Li Authors * Rong-fang Feng View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rui Ma View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Peng Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xu Ji View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhen-xiang Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Meng-meng Li View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jia-wei Jiao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Li Guo View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS R.-f.F., and R.M. collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. L.G., P.W., and X.J.

participated in writing of the manuscript. R.-f.F., R.M., L.G., and P.W. conceived and designed this study. Z.-x.Z. extracted the data and modified the paper. M.-m.L. and J.-w.J. extracted

the data. All authors reviewed the paper, read and approved the final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Peng Wang or Li Guo. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of the Article contained an error in the Author list, where the authors Rong‑fang Feng and Rui Ma

were erroneously listed as equally contributing authors. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the

original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in

the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Feng, Rf., Ma, R., Wang, P. _et al._ Efficacy of escitalopram for poststroke

depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. _Sci Rep_ 12, 3304 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05560-w Download citation * Received: 16 September 2021 * Accepted: 10

January 2022 * Published: 28 February 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05560-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative