Transcriptomic insight into the translational value of two murine models in human atopic dermatitis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This study sought to develop a novel diagnostic tool for atopic dermatitis (AD). Mouse transcriptome data were obtained via RNA-sequencing of dorsal skin tissues of CBA/J mice

affected with contact hypersensitivity (induced by treatment with 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene) or brush stimulation-induced AD-like skin condition. Human transcriptome data were collected

from German, Swedish, and American cohorts of AD patients from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. edgeR and SAM algorithms were used to analyze differentially expressed murine and human

genes, respectively. The FAIME algorithm was then employed to assign pathway scores based on KEGG pathway database annotations. Numerous genes and pathways demonstrated similar dysregulation

patterns in both the murine models and human AD. Upon integrating transcriptome information from both murine and human data, we identified 36 commonly dysregulated differentially expressed

genes, which were designated as a 36-gene signature. A severity score (AD index) was applied to each human sample to assess the predictive power of the 36-gene AD signature. The diagnostic

power and predictive accuracy of this signature were demonstrated for both AD severity and treatment outcomes in patients with AD. This genetic signature is expected to improve both AD

diagnosis and targeted preclinical research. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS MULTIFACETED ANALYSIS OF CROSS-TISSUE TRANSCRIPTOMES REVEALS PHENOTYPE–ENDOTYPE ASSOCIATIONS IN ATOPIC

DERMATITIS Article Open access 02 October 2023 AN UNBIASED TISSUE TRANSCRIPTOME ANALYSIS IDENTIFIES POTENTIAL MARKERS FOR SKIN PHENOTYPES AND THERAPEUTIC RESPONSES IN ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Article Open access 02 June 2025 POTENTIAL SHARED MECHANISMS IN ATOPIC DERMATITIS AND TYPE 2 DIABETES IDENTIFIED VIA TRANSCRIPTOMIC AND MACHINE LEARNING APPROACHES Article Open access 16

December 2024 INTRODUCTION Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) often exhibit an itchy rash, xerosis, skin barrier defects, chronic relapses, and emotional distress, which reduces their

quality of life1. The diagnosis of AD is generally based on visible clinical symptoms, with limited therapeutic options available for this condition. The most common diagnostic criteria and

severity scoring tools are the Hanifin and Rajka criteria2 and the SCORing AD (SCORAD) index3, respectively. Various murine models have been developed for studying AD; however, their ability

to recapitulate the pathophysiological features and complex clinical manifestations of human AD is limited. In the contact hypersensitivity (CHS) model, hapten 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

is applied to the skin to stimulate keratinocytes, which produce various biochemical mediators, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α4. These responses promote the

migration and maturation of dermal dendritic cells, which then migrate to draining lymph nodes, presenting contact allergens to naïve T cells. In the skin-scratching stimulation (SSS) model,

mice exhibit a temporary self-scratching behavior within a few minutes of brush stimulation. This leads to the physiological stimulation of the skin via activation of the substance P

signaling pathway, following the binding of tachykinin receptor 15,6. Using these murine models, we previously suggested—from a molecular genetic perspective—that itching is caused by

induction of damage to the chemical/physical skin barrier, which is related to the rate of wound healing, particularly in the case of inflammatory reactions, and pain signal intensity7. We

also noted that pruritus and a skin barrier disorder were representative symptoms of AD. Therefore, we employed these two pruritus murine models, which demonstrate early stages of skin

reactions, rather than the chronic AD NC/Nga mouse model8. In this study, we developed objective AD criteria based on molecular signatures that can be applied as potential tools for

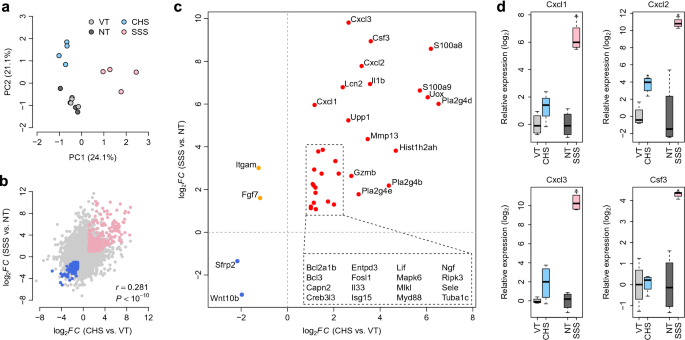

improving the accuracy of AD diagnosis and evaluating AD treatment outcomes9. RESULTS GENE DYSREGULATION PATTERNS IN CHS AND SSS MURINE MODELS We prepared 16 polyA-enriched RNA-seq libraries

of mouse skin samples with four biological replicates per group (vehicle control, VT; non-treated control, NT; CHS model, and SSS model). In total, 13,259 genes were identified with average

expression levels > 1 transcript per million. To assess transcriptome heterogeneity within the different murine models, we conducted principal component analysis of the whole-genome gene

expression data, which revealed distinct transcriptome patterns between the VT and CHS and NT and SSS samples (Fig. 1a). However, the first and second principal components of the VT and NT

samples did not differ significantly (Fig. 1a), suggesting similar transcriptomic landscapes for these two controls. To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in both murine models,

we compared gene expression patterns between the VT and CHS samples, and between the NT and SSS samples. Using the following cut-offs: a false discovery rate (FDR) < 5% and fold-change

(FC) > 2, 993 upregulated and 1,214 downregulated DEGs were detected in the CHS samples, relative to the VT samples (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Comparatively, 1,608 and 999 DEGs

were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in the SSS samples, relative to the NT samples (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). Interestingly, FC gene expression values in the VT and CHS

groups were positively correlated with those observed between the NT and SSS groups (Pearson’s correlation (_r_) = 0.281, _P_ < 10−10). In both models, 292 and 293 DEGs were commonly

upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Fig. 1b), suggesting that a considerable number of DEGs shared similar dysregulation patterns in the two murine models. DYSREGULATED PATHWAYS IN

THE MURINE MODELS To investigate transcriptomic alterations in the two murine models, we examined dysregulated pathways based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

database annotations10,11,12. For each pathway, we obtained a pathway score using the FAIME algorithm, with a higher pathway score indicating higher overall expression. In total, 39

upregulated and 49 downregulated KEGG pathways (_t_-test: corrected _P_ < 0.05) were detected in CHS samples compared with VT samples (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). Additionally, 46

and 23 pathways were found to be upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in SSS samples, relative to the NT samples (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). We then investigated the

dysregulated pathways shared between the two murine models. Eleven KEGG pathways were commonly upregulated in both models, including TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway,

RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, apoptosis, and necroptosis (Supplementary Fig. S1). Lipoic acid metabolism and Wnt signaling pathway, were commonly downregulated in the two murine

models (Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, the Rap1 signaling pathway was dysregulated in a contradictory manner in the two murine models (downregulated in the CHS model and upregulated

in the SSS model) (Supplementary Fig. S1). We further investigated commonly dysregulated DEGs within these prioritized pathways. In total, 32 DEGs were commonly upregulated in the CHS and

SSS samples, including _Cxcl1_, _Cxcl2_, _Cxcl3_, _Csf3_, _Il1b_, _Mmp13_, _S100a8_, and _S100a9_ (Fig. 1c). _Sfrp2_ and _Wnt10b_ were commonly downregulated in both murine models (Fig. 1c),

while _Fgf7_ and _Itgam_ were downregulated in the CHS model and upregulated in the SSS model (Fig. 1c). Using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), we further validated the

expression patterns of _Cxcl1_, _Cxcl2_, _Cxcl3_, and _Csf3_, all of which exhibited significant upregulation in the SSS samples, compared with the NT samples (one-tailed _t_-test: _P_ = 1.2

× 10−4 for _Cxcl1_; _P_ = 8.8 × 10−3 for _Cxcl2_; _P_ = 3.7×10−6 for _Cxcl3_; _P_ = 6.7 × 10−3 for _Csf3_). Significant or marginal upregulation of _Cxcl1_, _Cxcl2_, and _Cxcl3_ was also

observed in the CHS samples, compared with the VT samples (one-tailed _t_-test: _P_ = 5.4 × 10−2 for _Cxcl1_; _P_ = 1.4 × 10−3 for _Cxcl2_; _P_ = 6.8 × 10−2 for _Cxcl3_) (Fig. 1d).

COMPARISON OF PATHWAY DYSREGULATION BETWEEN MURINE MODELS AND HUMAN AD To evaluate the extent to which the CHS and SSS murine models translationally recapitulated the pathology of human AD,

we compared the transcriptomic profiles of the murine models with those of the German (DE)13 and Swedish (SE) AD cohorts14. For both the human cohorts, KEGG pathway scores were computed for

the control skin and AD lesional skin samples using the _FAIME_ algorithm. We utilized a Student’s _t_-test to prioritize the dysregulated KEGG pathways between the control and AD skin

samples, and recorded the _t_-statistic value for each comparison. For a given pathway, a positive t-statistic suggested the upregulation of a potential pathway in AD skin, relative to the

control. A negative t-statistic suggested the downregulation of a potential pathway in AD. The t-statistics of both human AD cohorts were positively correlated with those of the VT and CHS

samples (_r_ = 0.158, _P_ = 1.4 × 10−2 for DE; _r_ = 0.429, _P_ < 10−-10 for SE) (Fig. 2a). A similar positive correlation was observed when comparing the human AD cohorts and the SSS

model (_r_ = 0.338, _P_ = 6.9 × 10−8 for DE; _r_ = 0.544, _P_ < 10−10 for SE) (Fig. 2b). The results suggest that the pathways dysregulated in the murine models were more likely to be

dysregulated in human AD skin, and that many pathways shared similar dysregulation patterns in murine models and human AD. Figure 2c illustrates several KEGG pathways commonly upregulated in

the human AD cohorts and both murine models, including TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, necroptosis, and apoptosis. In contrast, the

Wnt signaling pathway was commonly downregulated in human AD lesional skin from the SE cohort (but not the DE cohort) and in both murine models (Fig. 2c). We also observed several pathways

exhibiting upregulation in both human cohorts but not in the murine models, such as those related to fructose and mannose metabolism (Fig. 2c). To evaluate the effect of age on the

translational value of the two murine models, one more AD cohort from the United States (US1)15 was investigated, which included both pediatric and adult subjects. We found that the

_t_-statistics of the KEGG pathways of both the pediatric and adult groups were positively correlated with those of the VT and CHS samples (_r_ = 0.526, _P_ < 10−10 for the pediatric

group; _r_ = 0.348, _P_ = 2.5 × 10−8 for the adult group) (Supplementary Fig. S2a). A similar positive correlation was observed when comparing the US1 cohort with the SSS model (_r_ = 0.295,

_P_ = 2.9 × 10−6 for the pediatric group; _r_ = 0.479, _P_ < 10−10 for the adult group) (Supplementary Fig. S2b). These results suggest that the translational power of the two murine

models is not likely to be affected by the age of the AD patients. TRANSLATIONAL CONTRIBUTION OF MURINE MODELS TO AD BIOMARKER DEVELOPMENT To understand whether incorporation of the

transcriptomic information from the murine models may potentially aid in the development of biomarkers for human AD, we focused on dysregulated DEGs shared between the murine models and the

human AD cohorts. As shown in Figure 1b, we identified 292 commonly upregulated and 293 commonly downregulated genes in the CHS and SSS models. We mapped these genes to their corresponding

human orthologs and found that 36 of the genes were also dysregulated in the DE and SE cohorts (FDR < 10% and FC > 1.5). We designated these 36 genes as a 36-gene signature (Table 1)

and assigned a weight of 1 and -1 to upregulated and downregulated DEGs in human lesional skin, respectively. To validate the diagnostic power of the 36-gene signature, we investigated its

predictive performance using the US2 cohort16 for independent validation. To statistically assess the predictive power of the 36-gene signature, a severity score (AD index) was assigned to

each human sample. AD index scores were significantly correlated with the SCORAD index scores for both lesional (_r_ = 0.815, P < 10−10) (Fig. 3a) and non-lesional (_r_ = 0.639, _P_ = 4.8

× 10−7) samples (Supplementary Fig. S3). AD index scores of lesional samples were significantly higher than those of non-lesional samples (_t_-test: _P_ = 5.4 × 10−5) (Supplementary Fig.

S4). Finally, clinical treatment outcome was associated with AD index scores in both lesional and non-lesional skin samples. AD index scores of human skin subjected to the 2-week treatment

were significantly lower than baseline values (paired _t_-test: _P_ = 3.4 × 10−6 for lesional samples and _P_ = 5.2 × 10−3 for non-lesional samples) (Fig. 3b). However, AD index scores of

lesional skin subjected to the 12-week treatment were only marginally lower than those of the skin subjected to the 2-week treatment (paired _t_-test: _P_ = 5.4 × 10−2). AD index scores of

non-lesional skin between the 2- and 12-week time points did not differ significantly (paired _t_-test: _P_ = 3.7 × 10−1) (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that the 36 gene-based AD index may

potentially serve as a proxy for an anti-AD therapeutic response. To determine whether the transcriptomic information from the murine model can contribute to the development of AD skin

biomarkers, a resampling test was conducted following the scheme suggested by Venet et al.17. We generated a human gene pool (designated as Human in Fig. 3c) containing AD-related genes

commonly dysregulated in the DE and SE cohorts. We then artificially constructed 1,000 random gene signatures, identical in size to that of the 36-gene signature, by randomly selecting genes

from the human AD-related gene pool. For each resampled signature, we calculated a severity score based on the gene expression within the resampled signature for all the lesional samples.

The correlation between SCORAD index scores and gene expression-based severity scores was recorded for each random gene signature, which measured the predictive power of the random gene set.

The correlation coefficient r of our 36-gene signature was significantly higher than that of the artificial gene signatures (right-tailed: _P_ = 0.046) (Fig. 3c). The resampling test

suggested that including the transcriptomic information from the murine model improved the predictive accuracy of the AD severity gene signature. To determine whether the CHS or SSS murine

model had a greater potential to improve the performance of the AD gene signature, we conducted two more rounds of the resampling test. We generated a gene pool (Human + CHS) containing the

DEGs commonly dysregulated in both the CHS murine model and human cohorts, and artificially constructed 1000 random gene signatures by randomly selecting 36 genes from the Human + CHS gene

pool. We computed the severity score for each resampled signature, and the correlation between the SCORAD index scores and severity scores was recorded for each random gene signature. We

also generated a gene pool (Human + SSS) containing the DEGs commonly dysregulated in both the SSS murine model and the human cohorts. A 1,000-time resampling test based on the Human + SSS

gene pool was conducted using the aforementioned method. The predictive power of the Human + CHS signature was significantly higher than that of the signatures generated from the Human + SSS

gene pool and the human AD-related gene pool (_t_-test: _P_ < 10−10) (Fig. 3c). This finding indicated that the incorporation of the CHS murine model’s transcriptomic information

substantially benefited the development of AD biomarkers. A previous study suggests that the transcriptome of IL-23-injected mice show strong homology with the human AD transcriptome and may

best represent the AD phenotype18. To determine whether the IL-23-injected murine model had a potential to improve the performance of the AD gene signature, we generated a gene pool (Human

+ IL-23) containing the DEGs commonly dysregulated in both the IL-23-injected murine model and human cohorts. A 1,000-time resampling test based on the Human + IL-23 gene pool was conducted

using the aforementioned method. We found that the predictive power of the Human + IL-23 signatures was significantly higher than that of the Human + SSS signatures (_t_-test: _P_ <

10−10), but significantly lower than that of the Human + CHS signatures (_t_-test: _P_ < 10−10) (Fig. 3c). In addition, we did not find significant difference between Human and Human +

IL-23 gene pools (_t_-test: _P_ = 0.780) (Fig. 3c). These findings further suggest the superior translational value of the CHS murine model. SUPERIOR PREDICTIVE POWER OF THE 36-GENE

SIGNATURE We compared the predictive power of our 36-gene signature against the following AD severity biomarkers published by Ungar et al.19: a 10-gene signature for lesional skin, and a

14-gene signature for non-lesional skin (Supplementary Table S9). The 10-gene- and 14-gene-based severity scores were significantly correlated with the SCORAD index scores for both lesional

and non-lesional samples from the US2 cohort (_r_ = 0.671, _P_ < 10−10 for lesional samples; _r_ = 0.449, _P_ = 9.4 × 10−10 for non-lesional samples) (Fig. 4a). To compare the

performances of the published 10-gene signature and our proposed 36-gene signature, a resampling test was performed 1,000 times by randomly selecting ten genes from our proposed 36-gene

signature. The predictive power of the random 10-gene signature was significantly higher than that of the published 10-gene signature for lesional samples from the US2 cohort (left-tailed:

_P_ < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). We also applied a resampling test to compare the performance of our 36-gene signature with that of the published 14-gene signature for non-lesional samples. As

shown in Figure 4b, the predictive power of the random 14-gene signature was significantly higher than that of the published 14-gene signature for non-lesional samples from the US2 cohort

(left-tailed: _P_ = 0.023). These results indicated the superior AD severity-predicting power of our proposed 36-gene signature. DISCUSSION We integrated the transcriptomic information

obtained for the murine models with that of human AD cohorts and identified a commonly dysregulated 36-gene signature. The 36-gene signature demonstrated sufficient diagnostic power to

accurately predict the severity of AD and treatment outcomes in AD patients. AD is diagnosed based on its clinical features; therapeutic strategies for AD are limited to the hydration of the

skin, topical corticosteroid application, or suppression of the immune system. Therefore, a reliable method for the molecular diagnosis of AD is urgently required. The significant role of

ion channel in AD has been determined in previous studies, for example, various transient receptor potential (TRP) channels including _TRPA1_, _TRPV1-4_, and _TRPM8_, have been shown to be

responsible for the transmission of itch sensation20,21,22. Although the alterations of the transcriptome and integrative analysis of murine and human transcriptomes in disease conditions

have been extensively studied, the number of channels in each subfamily among AD animal models largely varies and datasets from regions of interest and approaches for transcriptome analysis

differ. In our study, to diminish the discrepancies between various animal AD models and improve the accuracy of AD diagnosis, we identified commonly dysregulated ion channel gene signature

by including two animal AD models. The informative transcriptomes of the CHS and SSS models obtained by us will serve as primary resources for providing insights into the molecular changes

associated with AD and AD-related biological studies. In our previous study7, keratinization was found to be a commonly upregulated biological process in both the CHS and SSS murine models,

although not all the observed skin lesions were severe. Our 36-gene signature included four KRT genes, among which _KRT6A_, _KRT6B_, and _KRT16_ were upregulated and _KRT15_ was

downregulated in AD samples. The _KRT6_ and _KRT16_ keratin gene pair is constitutively expressed and activated in epidermal hyperproliferation23,24. However, _KRT15_ encodes a type I

keratin, which does not serve as a natural type II expression partner, and its expression is not compatible with keratinocyte activation. In accordance with our study findings, _KRT15_ is

known to be downregulated in the hyperproliferating epidermis to maintain the hyperplastic phenotype25,26. Skin barrier dysfunction in AD is associated with alterations in key genes involved

in keratinocyte differentiation and formation of structural proteins for skin barrier elements. We found that genes encoding structural proteins (TUBB, KRT, DSC, and FSCN) and epidermal

differentiation complex components (SPRR1A and SPRR1B) known to be associated with AD27,28,29,30 were upregulated in AD samples. We also found that genes encoding the Ca2+-binding proteins

S100A8 and S100A9, which are members of an inflammatory protein complex, were upregulated in AD samples. This is consistent with previous reports of their upregulation in AD31 and

psoriasis32. The intracellular concentration of Ca2+ regulates keratinocyte differentiation, and alterations in the extracellular Ca2+ gradient in the epidermis may be responsible for

upregulating a group of S100 proteins, including S100A8 and S100A933. We observed that _Sfrp2_ was downregulated in both murine models, whereas _Sfrp4_ was only downregulated in the CHS

model. SFRP family proteins encoded by _Sfrp_ genes bind Wnt ligands, thereby inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway and subsequently controlling cell proliferation and differentiation34.

SFRP4, in particular, which is reportedly downregulated in the lesional skin of murine psoriasis models and human psoriasis patients, has also been reported to inhibit keratinocyte

hyperproliferation and epidermal hyperplasia35. A previous study has identified genes that are differentially expressed in AD compared to normal skin specimens from several types of animal

AD models and humans with AD18. Among 6 common AD-like murine models, an IL-23-injected mouse model showed a transcriptomic profile with the highest similarity to the human AD transcriptome.

This model shows remarkable innate immune activation and some epidermal alterations, increased neutrophil counts, and sparse amounts of eosinophils and mast cells, which can be found in

human AD patients18. In our study, we found many pathways with a similar dysregulation pattern in both the CHS and SSS murine models and human AD patients and revealed that including

information obtained from murine models improve the accuracy of the gene signature for predicting AD severity. In another previous study, based on meta-analysis derived atopic dermatitis

(MADAD) transcriptome, Ewald et al. identified a robust AD signature composed of 19 genes36. Sixteen of these nineteen human genes can be successfully mapped to mouse orthologs. We found

that the expression fold changes of these MADAD genes were positively correlated with those of the corresponding mouse orthologous genes in both the CHS and SSS models (Supplementary Fig.

S5). Moreover, 6 and 7 genes out of the 16 mouse orthologs were significantly dysregulated in the CHS and SSS models, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6); this suggests the strong intrinsic

connection between the MADAD and CHS/SSS transcriptomes. Although our study was limited to European and American AD patients, recent studies have reported a unique skin phenotype in Asian

AD patients, which is a combination of that observed in European and American atopic and psoriasis patients characterized by increased TH17/TH22 polarization. Hence, our 36-gene signature is

expected to further improve our understanding of AD in Asian patients37. Animal models do not completely reflect the transcriptomic and gene pathways activated in human AD skin, resulting

in inconsistent non-clinical and clinical AD trial results. The focus of our study was to integrate AD diagnostic criteria to overcome these inconsistencies, and our 36-gene signature was

validated for use in further diagnostic and translational studies involving AD. The findings of our study provide a useful tool for AD diagnosis or for screening compounds in the development

of targeted AD therapies. METHODS MURINE MODEL TRANSCRIPTOME DATA The details of our experiment have been described previously7. The experiments were approved by the ethics committee of

Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea (review numbers: 2018-00082 and 2018-00083). The CHS model was generated using a method modified from a local lymph node assay38,39, and the SSS model was

generated using a method described previously, with modifications5,6. All methods were conducted in accordance with IACUC guidelines and regulations for animal testing. Briefly, total RNAs

were extracted from dorsal skin tissues (four samples/group) using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression of all annotated

mouse mRNAs in the Ensembl database40 was quantified using the Sailfish pipeline41 with default settings. QUANTITATIVE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (QPCR) All reactions were performed according

to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the RNA to cDNA EcoDry Premix (Double Primed) (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Kusatsu, Japan), and quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (qPCR) was performed using LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a LightCycler 2.0 instrument (Roche). DETERMINATION OF DEGS USING MOUSE

RNA-SEQ DATA The edgeR algorithm42 was employed with default settings to identify DEGs (CHS vs. VT and SSS vs. NT) using the mouse RNA-seq data. Genes with FDR < 5% and FC values > 2

were deemed to be differentially expressed. HUMAN MICROARRAY DATA The following three human AD cohorts from the Gene Expression Omnibus database43 were investigated in this study: DE, based

on the Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 expression beadchip (GSE60709)13; SE, based on the Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array (GSE6012)14; US1, based on the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0

Array (GSE107361)15; and US2, based on the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (GSE58558)16. Fourteen control and twelve AD lesional skin samples from the DE cohort, as well as ten

control and ten AD lesional skin samples from the SE cohort, were included. The DE and SE cohorts were used to prioritize DEGs/pathways between the lesional AD and control samples. The US1

cohort was used to evaluate the effect of age on the translational value of our murine models. In total, there were 18 pediatric control samples, 19 pediatric AD lesional samples, 11 adult

control samples, and 20 adult lesional sample from the US1 cohort. The US2 cohort was used as the validation dataset; it contained 56 lesional and 53 non-lesional skin biopsy specimens

obtained from 19 AD patients at three separate time points: day 1 (baseline), week 2 (after 2 weeks of cyclosporine treatment), and week 12 (after 12 weeks of cyclosporine treatment). For a

gene with multiple probes/probesets, the geometric mean of all probes/probesets mapped to the gene was used to measure the expression level. The SAM algorithm44 was used to compare the

log2-transformed gene expression between lesional AD and control samples. FDR was controlled using the q-value method45. Genes with FDR < 10% were deemed to be differentially expressed.

PATHWAY SCORE The FAIME algorithm46 was applied to compute the gene expression-based pathway scores for samples from the murine models and human cohorts. The FAIME tool calculated the

pathway scores using the rank-weighted gene expression of individual samples, converting the transcriptomic data of each sample to the pathway-level information. Student’s t-tests were

performed to prioritize the dysregulated pathways between the control and AD samples. AD INDEX We followed a scoring scheme used in our previous studies47,48,49,50 to assign each human

patient an AD index, which is a linear combination of weighted gene expression values: $$AD=\sum_{i=1}^{n}{w}_{i}({e}_{i}-{\mu }_{i})/{\tau }_{i}$$ where n is the number of genes; _w__i_ is

the weight of gene _i_ (1 and − 1 for upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively); _e__i_ is the expression level of gene _i_; and _μ__i_ and _τ__i_ are the mean and standard

deviation of the gene expression values for gene _i_ across all samples, respectively. A higher AD index implies a more severe AD status. DATA AVAILABLITY Human cohort datasets related to

this study can be found at the Gene Expression Omnibus database. RNA sequencing data are available from the corresponding author upon request. REFERENCES * Schneider, L. _et al._ Atopic

dermatitis: A practice parameter update 2012. _J Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 131, 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.672 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hanifin, J. M.

& Rajka, G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. _Acta Derm. Venereol. Suppl._ 60, 44–47 (1980). Google Scholar * Stalder, J. F. _et al._ Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: The

SCORAD index Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. _Dermatology_ 186, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000247298 (1993). Article Google Scholar * Christensen, A.

D. & Haase, C. Immunological mechanisms of contact hypersensitivity in mice. _APMIS_ 120, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02832.x (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Yamaoka, J. & Kawana, S. A transient unresponsive state of self-scratching behaviour is induced in mice by skin-scratching stimulation. _Exp. Dermatol._ 16, 737–745.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00593.x (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yilinuer, H., Yamaoka, J. & Kawana, S. Effect of epinastine hydrochloride on murine

self-scratching behavior after skin-scratching stimulation. _Arch. Dermatol. Res._ 302, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-009-1006-y (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kim,

Y.-W. _et al._ Prediction of itching diagnostic marker through RNA sequencing of contact hypersensitivity and skin scratching stimulation mice models. _Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol._ 23,

151–159. https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2019.23.2.151 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jin, H., He, R., Oyoshi, M. & Geha, R. S. Animal models of atopic

dermatitis. _J. Invest. Dermatol._ 129, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.106 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gallant, M. J. & Ellis, A. K. What can

we learn about predictors of atopy from birth cohorts and cord blood biomarkers?. _Ann. Allergy Asthm. Immunol._ 120, 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.12.003 (2018). Article

Google Scholar * Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. _Protein Sci._ 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG: Integrating viruses and cellular organisms.

_Nucleic Acids Res._ 49, D545-d551. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa970 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rodriguez, E. _et al._ An integrated epigenetic and transcriptomic analysis

reveals distinct tissue-specific patterns of DNA methylation associated with atopic dermatitis. _J. Invest. Dermatol._ 134, 1873–1883. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.87 (2014). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mobini, R. _et al._ A module-based analytical strategy to identify novel disease-associated genes shows an inhibitory role for interleukin 7 Receptor in

allergic inflammation. _BMC Syst. Biol._ 3, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-3-19 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Brunner, P. M. _et al._ Early-onset

pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by T(H)2/T(H)17/T(H)22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 141, 2094–2106.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.040 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Khattri, S. _et al._ Cyclosporine in patients with atopic dermatitis modulates activated

inflammatory pathways and reverses epidermal pathology. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 133, 1626–1634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.003 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Venet, D., Dumont, J. E. & Detours, V. Most random gene expression signatures are significantly associated with breast cancer outcome. _PLoS Comput. Biol._ 7, e1002240.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002240 (2011). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ewald, D. A. _et al._ Major differences between human atopic dermatitis and

murine models, as determined by using global transcriptomic profiling. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 139, 562–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.029 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Ungar, B. _et al._ An integrated model of atopic dermatitis biomarkers highlights the systemic nature of the disease. _J. Invest. Fermatol._ 137, 603–613.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.037 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lucaciu, O. C. & Connell, G. P. Itch sensation through transient receptor potential channels: A

systematic review and relevance to manual therapy. _J. Manip. Physiol. Ther._ 36, 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.05.018 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Seo, S. H., Kim, S.,

Kim, S. E., Chung, S. & Lee, S. E. Enhanced thermal sensitivity of TRPV3 in keratinocytes underlies heat-induced pruritogen release and pruritus in atopic dermatitis. _J. Invest.

Dermatol._ 140, 2199-2209.e2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2020.02.028 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Reese, R. M. _et al._ Behavioral characterization of a

CRISPR-generated TRPA1 knockout rat in models of pain, itch, and asthma. _Sci. Rep._ 10, 979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57936-5 (2020). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Machesney, M., Tidman, N., Waseem, A., Kirby, L. & Leigh, I. Activated keratinocytes in the epidermis of hypertrophic scars. _Am. J. Pathol._ 152, 1133–1141 (1998). CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stoler, A., Kopan, R., Duvic, M. & Fuchs, E. Use of monospecific antisera and cRNA probes to localize the major changes in keratin expression

during normal and abnormal epidermal differentiation. _J. Cell. Biol._ 107, 427–446. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.107.2.427 (1988). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Waseem, A. _et al._

Keratin 15 expression in stratified epithelia: downregulation in activated keratinocytes. _J. Invest. Dermatol._ 112, 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00535.x (1999).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Werner, S. & Munz, B. Suppression of keratin 15 expression by transforming growth factor beta in vitro and by cutaneous injury in vivo. _Exp.

Cell. Res._ 254, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1006/excr.1999.4726 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Totsuka, A., Omori-Miyake, M., Kawashima, M., Yagi, J. & Tsunemi, Y.

Expression of keratin 1, keratin 10, desmoglein 1 and desmocollin 1 in the epidermis: Possible downregulation by interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 in atopic dermatitis. _Eur. J. Dermatol._

27, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2017.2985 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ma, Y. _et al._ Fascin 1 is transiently expressed in mouse melanoblasts during development

and promotes migration and proliferation. _Development_ 140, 2203–2211. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.089789 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * McAleer, M. A. _et

al._ Severe dermatitis, multiple allergies, and metabolic wasting syndrome caused by a novel mutation in the N-terminal plakin domain of desmoplakin. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 136,

1268–1276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.002 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Grzanka, A. _et al._ The effect of pimecrolimus on expression of genes

associated with skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis skin lesions. _Exp. Dermatol._ 21, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01417.x (2012). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Gittler, J. K. _et al._ Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. _J. Allergy

Clin. Immunol._ 130, 1344–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.012 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schonthaler, H. B. _et al._ S100A8-S100A9 protein

complex mediates psoriasis by regulating the expression of complement factor C3. _Immunity_ 39, 1171–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.011 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Bikle, D. D., Ratnam, A., Mauro, T., Harris, J. & Pillai, S. Changes in calcium responsiveness and handling during keratinocyte differentiation. Potential role of the calcium

receptor. _J. Clin. Invest._ 97, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci118501 (1996). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kawano, Y. & Kypta, R. Secreted antagonists

of the Wnt signalling pathway. _J. Cell. Sci._ 116, 2627–2634. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.00623 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bai, J. _et al._ Epigenetic downregulation of

SFRP4 contributes to epidermal hyperplasia in psoriasis. _J. Immunol._ 194, 4185–4198. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1403196 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ewald, D. A.

_et al._ Meta-analysis derived atopic dermatitis (MADAD) transcriptome defines a robust AD signature highlighting the involvement of atherosclerosis and lipid metabolism pathways. _BMC Med.

Genom._ 8, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-015-0133-x (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Noda, S. _et al._ The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic

dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 136, 1254–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Anderson, S. E., Siegel, P. D. & Meade, B. J. The LLNA: A brief review of recent advances and limitations. _J. Allergy_ 424203–424203, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/424203

(2011). Article Google Scholar * OECD. _Test No. 429: Skin Sensitisation: Local Lymph Node Assay_. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4, OECD Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264071100-en (2010). * Cunningham, F. _et al._ Ensembl 2015. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 43, D662-669. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1010 (2015). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Patro, R., Mount, S. M. & Kingsford, C. Sailfish enables alignment-free isoform quantification from RNA-seq reads using lightweight algorithms. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 32,

462–464. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2862 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package

for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. _Bioinformatics_ 26, 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Edgar, R., Domrachev, M. & Lash, A. E. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. _Nucleic Acids Res_ 30, 207–210.

https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/30.1.207 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tusher, V. G., Tibshirani, R. & Chu, G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied

to the ionizing radiation response. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 98, 5116–5121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.091062498 (2001). Article ADS CAS PubMed MATH PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Taylor, J., Tibshirani, R. & Efron, B. The “miss rate” for the analysis of gene expression data. _Biostatistics_ 6, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxh021 (2005).

Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Yang, X. _et al._ Single sample expression-anchored mechanisms predict survival in head and neck cancer. _PLoS Comput. Biol._ 8, e1002350.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002350 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, R. _et al._ Ion channel gene expression predicts survival in glioma

patients. _Sci. Rep._ 5, 11593. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11593 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Qian, Z. _et al._ Expression of nuclear factor,

erythroid 2-like 2-mediated genes differentiates tuberculosis. _Tuberculosis_ 99, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2016.04.008 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ko, J. H.

_et al._ Expression profiling of ion channel genes predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. _Mol. Cancer_ 12, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-12-106 (2013). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ko, J.-H. _et al._ Ion channel gene expression in lung adenocarcinoma: potential role in prognosis and diagnosis. _PLoS ONE_

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086569 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by the Basic Science

Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant Number: 2017R1D1A1B06035273). The study was also funded by Chung-Ang

University Research Grants in 2019. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Young-Won Kim and Eun-A Ko. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Physiology,

College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Korea Young-Won Kim, Donghee Lee, Yelim Seo, Seongtae Kim, Hyoweon Bang & Jae-Hong Ko * Department of Physiology, School of

Medicine, Jeju National University, Jeju, 63243, Korea Eun-A Ko & Sung-Cherl Jung * Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University Hospital, Seoul, 06973, Korea

Jung-Ha Kim * Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, Reno, NV, 89557, USA Tong Zhou Authors * Young-Won Kim View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eun-A Ko View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sung-Cherl Jung View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Donghee Lee View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yelim Seo View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Seongtae Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jung-Ha

Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hyoweon Bang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Tong Zhou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jae-Hong Ko View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Y.W.K., E.A.K. and T.Z. conceptualized the research. Y.W.K., D.L., Y.S. and S.K. conducted the experiments. E.A.K., T.Z. and J.H.K.1. analysed the results. S.C.J.,

J.H.K.3. and H.B. had oversight of the research activity. Y.W.K., E.A.K., T.Z. and J.H.K.1. wrote the initial draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence

to Tong Zhou or Jae-Hong Ko. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the

copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Kim, YW., Ko, EA., Jung,

SC. _et al._ Transcriptomic insight into the translational value of two murine models in human atopic dermatitis. _Sci Rep_ 11, 6616 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86049-w

Download citation * Received: 08 June 2020 * Accepted: 10 March 2021 * Published: 23 March 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86049-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative