Cyclands: cycling geo-located accidents, their details and severities

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Several cities and national authorities across the globe publish records on road accidents and crashes. This data is vital for road safety analysis, enabling researchers to develop

models to understand how different factors impact the frequency and severity of accidents. However, researchers studying cycling safety face additional challenges as datasets containing

solely cycling accidents are scarce, may contain errors, among others. Thus, we publish CYCLANDS: CYCling geo-Located AccideNts, their Details and Severities. CYCLANDS is a curated

collection of 30 datasets on cycling crashes to lower the barrier in objective cycling research comprising nearly 1.6 M cycling accidents. All observations include the severity and location

of the accident. This collection fosters the worldwide study of cycling safety by providing a testbed for researchers to develop tools and models for cycling safety analysis, ultimately

improving the safety of those who cycle. Measurement(s) Cycling Accident Technology Type(s) Reports Sample Characteristic - Location World SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS CYCLING AREA

CAN BE A CONFOUNDER AND EFFECT MODIFIER OF THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN HELMET USE AND CYCLISTS’ RISK OF DEATH AFTER A CRASH Article Open access 24 February 2022 CRASH AND DISENGAGEMENT DATA OF

AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES ON PUBLIC ROADS IN CALIFORNIA Article Open access 23 November 2021 ASSESSING INEQUALITY, IRREGULARITY, AND SEVERITY REGARDING ROAD TRAFFIC SAFETY DURING COVID-19 Article

Open access 23 June 2021 BACKGROUND & SUMMARY Cycling safety research seeks to understand how safe cycling is and what factors related to the individual, the bicycle, and the surrounding

environment influence cycling safety. Its research is vital because it envisages a safer environment for everyone to cycle, aiming to decrease the number of accidents and decrease the

severity of each accident. More, it is increasingly important to address the cycling safety issue better, potentially through infrastructure design and other interventions, as safety

concerns greatly discourage people from cycling1,2,3. Thus, improving the safety of cyclists is a crucial component in any cities’ strategy that seeks to increase cycling numbers3,4, while

also protecting those who cycle. Cycling safety is often measured in terms of the number of injuries or fatalities suffered by cyclists. It is often recorded on police reports or hospital

admissions. However, most incidents are often not reported (or underreported)5,6, resulting in underestimates in gauging how (un)safe cycling is. Nevertheless, accident or crash records are

vital because they form the basis for cycling safety research. Researchers use these cycling accidents records for analyzing how factors such as demographic data, built environment, weather,

and behavior increase or decrease the risk cyclists face of being involved or injured in an accident7. For instance, accident records act as the foundation for accident frequency and

severity models where researchers analyze and quantify which factors impact the outcome of accidents and what measures should be taken to protect cyclists. Fortunately, there is a growing

number of cities that are publishing road accident data. However, this data is often published for all transport modes, making it difficult for researchers who only want to focus on

vulnerable road users and the particular case of cyclists. Not only this, but cycling safety researchers face many other challenges when working with the provided data. First, accident data

is often fragmented into different files, where distinct files contain location information, anonymized personal characteristics, involved vehicle attributes, weather, and road conditions,

among others. All different files must be compiled and merged to account for all the accident attributes captured. Second, data specifications differ for each authority publishing the

dataset, with even injury severity levels specific to a single country or region. The third and final main challenge is that the published data often contain errors (e.g., accident

coordinates wrongly located). Thus, researchers ought to perform a series of validation steps before even being able to study what makes an accident happen. Furthermore, all these challenges

also hamper the comparison and transferability of models on cycling safety from one location to another, hindering knowledge transfer from one location to the other. Hence, validated

datasets are required to lower the barrier of cycling safety research. To the best of our knowledge, such an extensive compilation of curated cycling accident records is non-existent today.

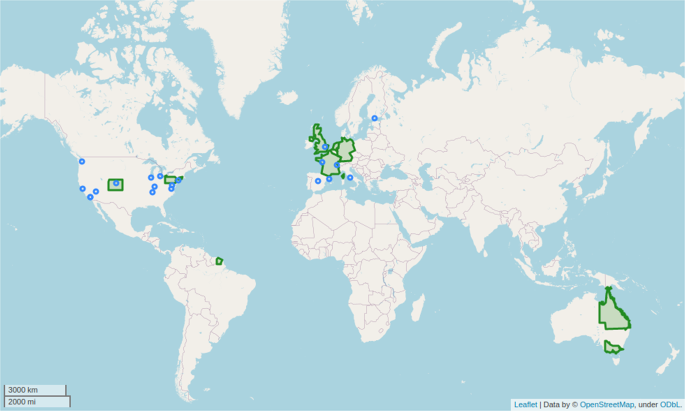

Thus, we publish CYCLANDS: CYCling geo-Located AccideNts, their Details and Severities. CYCLANDS is a collection of 30 datasets on objective cycling safety (i.e., based on accidents and

crashes counts), comprising 1.58 M cycling accident records with geographical scales ranging from country, region, or city-level data. The location of these datasets is laid out in Fig. 1.

We present this data in an easy-to-access CSV format, along with the code used for curating and validating each dataset from its source. We expect this data to be particularly beneficial for

researchers working with severity models (such as discrete outcome models) or similar. There is a need for a worldwide effort concerning improvement and standardization in crash data

collection to monitor the evolution of cycling safety plans and policies and implement the most effective safety countermeasures. Our collection provides a solid contribution to fulfill this

need. This collection of cycling accident records aims to facilitate the comparison of research, tools, and models on cycling safety. Each dataset was individually gathered, curated, and

validated to create a testbed for researchers. We aim to promote further the study and understanding of how, what, and why the risk faced by cyclists is still too high. Additionally, we have

published this collection on an online site for anyone to visualize and explore the pervasiveness of cycling accidents. Potentially, this site can promote the usage of the data and foster

research to protect cyclists further. METHODS Cycling accident data form the basis for any research on cycling safety. We begin by searching for publicly available data on road accidents

(including accidents involving cars, cyclists, pedestrians, and other road users). After downloading the original data, we filter the collected datasets, resulting in geo-located

observations with severity outcomes accidents where any number of cyclists are involved. We further curate and validate the collected data to ensure that the corresponding datasets are

easy-to-use and researchers do not need much validation work, essentially lowering the barrier on cycling safety analysis. DOWNLOADING DATA To make a collection of cycling accident data, we

began by searching for traffic accident data, as national authorities and cities more commonly publish these. Traffic accidents include observations of accidents involving all road users:

cars, public transportation, pedestrians, and cyclists, among others. We focused on looking for data from cities with different sizes, distinct continents, with different cycling modal

shares, and with different cycling maturities. However, our final collection was greatly influenced by the data availability, as most cities worldwide do not yet publish any data or

statistics on traffic safety. Thus, we included and downloaded data for different geographic scales (ranging from city, region, or country-wide data) and for which their licensing or usage

conditions do not hinder its usage for research purposes. Hence, to the best of our knowledge, at this point, all datasets in this collection are available under the public domain, allow for

reuse for scientific purposes, or have no licensing terms. Table 1 enumerates all 30 datasets in our collection, alongside some basic information for each, including the number of cycling

accidents. We searched traffic accident data in different platforms, such as cities’ open data portals and maps, national statistics bureaus, and national open data platforms. Typically

these platforms aggregate the data collected by police authorities and hospitals about traffic accidents, their locations, the severity outcomes, and the conditions in which the accident

happened. After reviewing the data to ensure that it could be reused for research purposes, it was downloaded in Excel, CSV, GeoJSON, or any other format. CYCLING DATA FILTERING Next, after

downloading the datasets, we filter the data such that in the end, we have accidents where cyclists were involved. This step is needed because cities’ accident and collision data include

accidents for all transport modes (motorized vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians). Since most cycling safety research rely solely on cycling observations or accidents where cyclists were

involved, we filter the original dataset only to have observations concerning bicycles. For that, we scrutinize each observation to identify whether a bicycle or cyclist was involved in the

accident. We scout such information from the user or vehicles involved, matching cases for which information is scattered across several sources. If a positive match is found, the

observation is filtered and added to the final cycling dataset. DATA CURATION The third and final step in our process consists of curating the cycling accident data. Once we filter the

cycling data, we curate the data, ensuring that the data can be easily handled by any researcher and consistent across the collection. Table 2 shows some information about the contents of

each dataset. We begin by curating the datasets based on the geographical location of accidents. Knowing the location of accidents is vital in safety research. Many use this information as

the foundation to analyze the built environment in such locations and how it impacts accidents. Although all added datasets include the location to some degree, the description of accident

locations varies greatly across datasets. Accident locations on each dataset can be detailed in one of four formats. Some describe locations based on geographic coordinates under the WSG 84

coordinate system, while others use specific coordinate systems or projections for the specific referenced region. Other datasets’ accident locations are not as simple or accurate, and

crashes are instead located with an address, the closest intersection to the location, or a description of the location (i.e., 200 meters west of the intersection of streets A and B). Given

the importance of crash locations, we standardize when feasible crash locations to a single format, which we chose to be the WSG 84 coordinate system given its wide use across many

applications worldwide. Thus, for datasets whose crash locations are in a projection system different from the WSG 84, we automatically project all accident locations to the WSG 84

coordinate system. This projection was applied to the following datasets, where the original coordinate system is detailed in parentheses: Barcelona (UTM), Helsinki (EPSG:3879), Netherlands

(EPSG:28992), Queensland (GDA94), and UK (.gov) (OSGR) datasets. For the datasets which do not contain any geographic coordinates and are instead located using an address or description, no

projection is applied (Detroit, Las Vegas, and Madrid datasets). Ultimately, this allows for locations to be more easily discoverable and circumvents researchers’ needs to identify and

project the coordinate system of the original dataset for those datasets which use a specific coordinate system to the related area. Next, we standardize the date and time details of each

observation. Knowing when an accident has happened allows researchers and urban authorities to identify the frequency of accidents and any related trends. Consequently, we standardize the

format of how accident dates are enumerated across datasets, easing the analysis of accidents over time. Finally, we filter accident observations to ensure that key fields (accident

severity, location, and date) do not contain any erroneous or missing elements. Localized accident severity models are vastly reliant on knowing both the location of accidents and their

outcome. With this in mind, we iterate over all observations and filter entries where these variables are either 0, NaN, None, empty, or correspond to an Unknown value. Equally important,

observations with incorrect or invalid data in these variables are also filtered. This means that observations with unfeasible locations or annotated outside their respective geographic

boundaries are removed (e.g., accidents outside the state of Colorado are removed for the Colorado dataset, or accidents with location [0.0, 0.0] for the Barcelona dataset are also

excluded). This step enables the inclusion of only observations which contain critical information for cycling safety research. In the end, we present our collection of cycling accident

datasets as presented in the Data Records section. With this procedure we ensure that all final records have detailed and accurate information about both accidents’ outcomes and where these

have happened, along with other accident information. Following a growing need for improving and standardizing crash data collection, this procedure ensures a solid step for monitoring

cycling safety data. This, in turn, can help research to design plans and policies and implement the most effective safety countermeasures to help protect cyclists. DATA RECORDS For each

dataset, we provide the curated data on cycling accidents enumerated in Table 1. We provide a copy of all data at Zenodo8, while also making data available in our repository9. Additionally,

we published an online site (https://ushift.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/cyclands) for easy exploration and interactive visualization of the datasets. Tables 3 and 4 expands Table 2 by providing more

detailed information about the data contained in each dataset. For each dataset, we provide the following files, where {_name_} corresponds to a given dataset: * cycling_safety_{name}.csv:

The data for each dataset is available as a comma separated value (CSV) file to allow easy use and exploration, regardless of the software used. This file contains all variables available

for the data, including the accident severity, location, date, among other variables. * cycling_safety_{name}.geojson: We also provide the data as a GeoJSON file to facilitate the usage of

this data in GIS-based software and other mapping tools, by reducing the need for researchers to transform the data into readable formats for such tools. * cycling_safety_{name}_summary.txt:

Contains a summary of the available variables for the dataset, together with some descriptive statistics of each variable. * cycling_safety_{name}_license.txt: The license or terms of use

for each dataset. The details for the license are provided in cycling_safety_{name}_legalcode.txt. * cycling_safety_{name}_legalcode.txt: The legal code for the license under which the data

is provided. TECHNICAL VALIDATION Substantial efforts were undertaken to verify and validate the quality of the collection of datasets presented here. Individual datasets were found,

selected, and obtained from reliable sources linked with cities, municipalities, statistical bureaus, or police records. Acquiring data from this set of sources is routinely employed by

cycling safety researchers and form the current research literature. Then, from the original data, a series of automated data validation steps were undertaken to further validate the

correctness of each individual dataset. Datasets were individually checked for key missing features (e.g., crash severity outcome or location) and invalid observations were removed from the

final curated data. Additionally, accident locations were compared to their expected locations, i.e., accidents from the Barcelona dataset were compared to Barcelona’s geographical borders.

Observations with geographical coordinates which lay far from the feasible dataset boundaries (inaccurate or faulty locations) were also removed from the final collection. Finally, we

perform a visual sanity check of the data for each dataset. We visualize accident locations using mapping tools and assess whether accident locations seem feasible. The code for all data

curation processes is publicly available, enabling further verification by other researchers. In effect, this ensures that researchers can readily use the data available under this

collection with the hope of expediting the barrier of cycling safety research. USAGE NOTES The collection of cycling accident datasets can be analyzed using different tools or software. We

provide each dataset in a single CSV file to facilitate data import into different tools or pieces of software, such as Python, R, NLogit, or others, which are typically used in cycling

safety research when using discrete outcome modes, ordered probability models or any machine learning approach. Key accident data for each dataset has been normalized so that information

like date (Date) and location (Latitude and Longitude) can be easily found and used. CODE AVAILABILITY Together with the collection of cycling safety datasets, we share the code used for

curating the datasets. All code has been written for Python3. We present the code under Jupyter notebooks, which provide step-by-step instructions on how each dataset was curated. The code

is available under the MIT license (https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT) and is available at https://github.com/U-Shift/cyclands. REFERENCES * Lawson, A. R., Pakrashi, V., Ghosh, B. &

Szeto, W. Perception of safety of cyclists in dublin city. _Accid. Analysis & Prev._ 50, 499–511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.05.029 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Aldred, R.

& Crosweller, S. Investigating the rates and impacts of near misses and related incidents among uk cyclists. _J. Transp. & Heal._ 2, 379–393 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Félix,

R., Moura, F. & Clifton, K. J. Maturing urban cycling: Comparing barriers and motivators to bicycle of cyclists and non-cyclists in lisbon, portugal. _J. Transp. & Heal._ 15, 100628

(2019). Article Google Scholar * Elvik, R. Cycling safety. _Cycl. for Sustain. Cities_ (2021). * Winters, M. & Branion-Calles, M. Cycling safety: quantifying the under reporting of

cycling incidents in vancouver, british columbia. _J. Transp. & Heal._ 7, 48–53 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Gildea, K., Hall, D. & Simms, C. Configurations of underreported

cyclist-motorised vehicle and single cyclist collisions: Analysis of a self-reported survey. _Accid. Analysis & Prev._ 159, 106264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106264 (2021).

Article Google Scholar * Vanparijs, J., Panis, L. I., Meeusen, R. & de Geus, B. Exposure measurement in bicycle safety analysis: A review of the literature. _Accid. Analysis &

Prev._ 84, 9–19 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Costa, M., Marques, M., Roque, C. & Moura, F. _CYCLANDS: CYCling geo-Located AccideNts, their Details and Severitie. zenodo_

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5603036 (2021). * Costa, M., Marques, M., Roque, C. & Moura, F. CYCLANDS: CYCling geo-Located AccideNts, their Details and Severities - Data. Online at

https://ushift.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/ushift.daemon/content/cyclands/data/ (2021). * Guàrdia Urbana de Barcelona. Aplicació accidents. Online at

https://opendata-ajuntament.barcelona.cat/data/en/dataset?q=accident&sort=fecha_publicacion+desc (2020). * Cambridgeshire County Council. Road traffic collisions: Location. Online at

https://data.cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk/dataset/road-traffic-collisions-location (2018). * City of Chicago. Traffic crashes. Online at

https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/Traffic-Crashes-Crashes/85ca-t3if, https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/Traffic-Crashes-Vehicles/68nd-jvt3, and

https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/Traffic-Crashes-People/u6pd-qa9d (2020). * DRCOG, CDOT. Crashes. Online at

https://data.drcog.org/data?category[0]=Transportation&page=1&q=crash&sort=title (2020). * Connecticut Transportation Safety Research Center. Connecticut crash data repository.

Online at https://www.ctcrash.uconn.edu/ (2020). * DRCOG, CDOT. Crashes. Online at https://data.drcog.org/data?q=crash&categories[0]=Transportation (2019). * Southeast Michigan Council

of Governments. Traffic crash data. Online at https://semcog.org/traffic-crash-data (2018). * Ministère de l’Intérieur. Bases de données annuelles des accidents corporels de la

circulationroutière - années de 2005 à 2019. Online at

https://www.data.gouv.fr/en/datasets/bases-de-donnees-annuelles-des-accidents-corporels-de-la-circulation-routiere-annees-de-2005-a-2019/ (2018). * DI - Département des infrastructures,

Office cantonal des transports. Accidents de la circulation (depuis 2010). Online at https://ge.ch/sitg/fiche/8139 (2021). * Statistical offices of the federal and state governments.

Accident atlas and opendata. Online at https://unfallatlas.statistikportal.de/ (2021). * Helsingin kaupunkiympäristön toimiala/Liikenne- ja katusuunnittelu. Traffic accidents in helsinki.

Online at https://hri.fi/data/en_GB/dataset/liikenneonnettomuudet-helsingissa (2020). * City of Las Vegas, Nevada Department of Transportation. Traffic crashes. Online at

https://opendataportal-lasvegas.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/traffic-crashes/data (2020). * Los Angeles Police Department. Traffic collision data from 2010 to present. Online at

https://data.lacity.org/A-Safe-City/Traffic-Collision-Data-from-2010-to-Present/d5tf-ez2w (2020). * Kentucky State Police. Traffic collisions. Online at

https://data.louisvilleky.gov/dataset/traffic-collisions (2020). * Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Accidentes de tráfico de la ciudad de madrid. Online at

https://datos.madrid.es/portal/site/egob/menuitem.c05c1f754a33a9fbe4b2e4b284f1a5a0/?vgnextoid=7c2843010d9c3610VgnVCM2000001f4a900aRCRD&vgnextchannel=374512b9ace9f310VgnVCM100000171f5a0aRCRD&vgnextfmt=default

(2020). * Département de Loire-Atlantique. Localisation des accidents sur les routes départementales de loire atlantique. Online at

https://data.nantesmetropole.fr/explore/dataset/224400028_localisation-accidents-sur-routes-departementales-de-loire-atlantique%40loireatlantique/export/?disjunctive.nom&disjunctive.nlieu&disjunctive.nveh&disjunctive.ntu&disjunctive.nbh&disjunctive.nbl&disjunctive.nind&sort=datetime&location=12,47.23904,-1.51388&basemap=jawg.streets

(2019). * Metro Nashville Police Department, Information Technology. Traffic accidents. Online at https://data.nashville.gov/Police/Traffic-Accidents/6v6w-hpcw (2021). * Rijkswaterstaat -

CIV. Bestand geRegistreerde Ongevallen Nederland (BRON). Online at https://data.amsterdam.nl/datasets/G6xF0loDvppzog/verkeersongevallen-bron-landelijk/ (2018). * NYC OpenData. Motor vehicle

collisions - crashes. Online at https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Public-Safety/Motor-Vehicle-Collisions-Crashes/h9gi-nx95 (2020). * City of Pasadena, CA City GIS. Traffic collisions. Online at

http://data.cityofpasadena.net/datasets/85f49ea583c24056968bee6e28162da4_0/data (2021). * Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. Penndot crash download map. Online at

https://pennshare.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=8fdbf046e36e41649bbfd9d7dd7c7e7e (2021). * Queensland Government Transport and Main Roads. Crash data from queensland roads.

Online at https://www.data.qld.gov.au/dataset/crash-data-from-queensland-roads (2020). * Richmond Police Department. Bicycle motor vehicle accidents. Online at

https://data.richmondgov.com/Community-Safety-and-Well-Being/Bicycle-Motor-Vehicle-Accidents/hcga-86ns/data (2015). * Roma Capitale, Ufficio Stampa, Corpo di Polizia Locale Roma Capitale,

Ufficio del Responsabile della Protezione dei Dati (RPD) & Ufficio di Scopo Innovazione per le Politiche Comportamentali. Incidenti stradali nel territorio di roma capitale - anno

2006-2019. Online at https://dati.comune.roma.it/catalog/it/dataset?q=incidenti&sort=score+desc%2C+dataset_last_update+desc (2019). * San Jose Enterprise GIS. Crash vehicles involved.

Online at https://data.sanjoseca.gov/dataset/crash-vehicles-involved1 (2021). * City of Seattle GIS Program. Collisions. Online at

http://data-seattlecitygis.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/5b5c745e0f1f48e7a53acec63a0022ab_0 (2020). * ITP and Merseyside Road Safety Partnership. Collideoscope. Online at

https://collideoscope.org.uk (2020). * Department for Transport. Road safety data. Online at https://data.gov.uk/dataset/cb7ae6f0-4be6-4935-9277-47e5ce24a11f/road-safety-data (2020). *

Department of Transport. Road crashes for five years - victoria. Online at https://discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/fatal-crashes-lives-lost-last-5-years-to-date (2020). * DC GIS Opendata.

Crashes in dc. Online at https://opendata.dc.gov/datasets/70392a096a8e431381f1f692aaa06afd_24 (2021). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was partially funded by Fundação para a

Ciência e Tecnologia via grant [PD/BD/142948/2018], and the authors are also grateful for the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia’s support through funding [UIDB/04625/2020] from the

research unit CERIS and [UIDB/50009/2020] from the research unit LARSyS. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Civil Engineering Research and Innovation for Sustainability, Instituto

Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Rovisco Pais, 1, 1049-001, Lisboa, Portugal Miguel Costa & Filipe Moura * Institute for Systems and Robotics, Instituto Superior Técnico,

Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Rovisco Pais, 1, 1049-001, Lisboa, Portugal Miguel Costa & Manuel Marques * Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil, Departamento de Transportes, Núcleo de

Planeamento, Tráfego e Segurança, Av. do Brasil 101, 1700-066, Lisboa, Portugal Carlos Roque Authors * Miguel Costa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Manuel Marques View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Carlos Roque View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Filipe Moura View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization: M.C., M.M., F.M.;

Methodology: M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Software: M.C.; Validation: M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Formal analysis: M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Resources: M.C., C.R.; Writing—original draft preparation:

M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Writing—review and editing: M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Visualization: M.C., M.M., C.R., F.M.; Supervision: M.M., C.R., F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the

published version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Miguel Costa. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s

Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Costa, M., Marques, M., Roque, C. _et al._

CYCLANDS: Cycling geo-located accidents, their details and severities. _Sci Data_ 9, 237 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01333-2 Download citation * Received: 16 December 2021 *

Accepted: 20 April 2022 * Published: 26 May 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01333-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative