Effect of hydrogen embrittlement on mechanical characteristics of dlc-coating for hydrogen valves of fcevs

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Diamond-like carbon (DLC) coating is a surface coating technology with excellent hydrogen permeation resistance and wear resistance. However, it is difficult to completely prevent

hydrogen permeation, and when hydrogen penetrates into the coating layer, the DLC coating is adversely affected. Therefore, we investigated the effect of hydrogen embrittlement on the

adhesion strength and wear resistance of the DLC coating layer. As the results of the research, the surface roughness of the DLC coating was increased by a maximum of 3.8 times with hydrogen

charging, and the delamination ratio of the DLC coating reached about 58%. In addition, the Lc3, which refers to the adhesion strength corresponding to the complete delamination of the DLC

coating, was decreased by a maximum of 2.0 N due to hydrogen permeation. In addition, the wear resistance decreased due to hydrogen permeation, and the exposed width of the substrate due to

wear increased by more than 4 times. It was also determined that hydrogen blistering or hydrogen-induced cracking occurred at the interface between the DLC coating and the chromium buffer

layer due to hydrogen permeation, which decreased the durability of the DLC coating. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS EFFECTS OF SILICON DOPING ON LOW-FRICTION AND HIGH-HARDNESS

DIAMOND-LIKE CARBON COATING VIA FILTERED CATHODIC VACUUM ARC DEPOSITION Article Open access 11 February 2021 OPTIMIZING GAS PRESSURE FOR ENHANCED TRIBOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF DLC-COATED

GRAPHITE Article Open access 02 October 2024 TRIBOCATALYTICALLY-ACTIVATED FORMATION OF PROTECTIVE FRICTION AND WEAR REDUCING CARBON COATINGS FROM ALKANE ENVIRONMENT Article Open access 19

October 2021 INTRODUCTION Climate change is a growing problem due to global warming and air pollution1. In particular, various greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrogen

dioxide, are emitted from automobiles using fossil fuels, which is attracting attention as a factor that accelerates environmental pollution. Thus, researchers are very interested in

researching and developing eco-friendly power sources to replace fossil fuels2,3. Among the various alternative power sources, hydrogen fuel cells represent an eco-friendly power source due

to having a relatively fast response and high efficiency, in addition to emitting only water4. Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) that use hydrogen fuel cells can be manufactured with

various systems and parts, such as a hydrogen supply system, hydrogen storage system, hydrogen fuel cells, power trains, etc. In particular, the hydrogen supply system is an essential system

that safely supplies and shuts off the hydrogen fuel from the hydrogen tank to the fuel cells5. In terms of the components of the hydrogen supply system, the hydrogen valve requires

particularly high durability due to being the component that operates most frequently during the operation of FCEVs. In particular, the plunger, which is one of the parts of the hydrogen

valve, is made of steel that is worn by friction with the core due to the reciprocating motion. This decreases both the performance and lifespan of the hydrogen valve, and in severe cases,

the operation of FCEVs may be impossible due to valve malfunction. Moreover, in an environment in which hydrogen exists, wear increases dramatically due to the defects and cracks formed

through hydrogen permeation into the surface of the plunger or core6. As a consequence, it is essential to apply a surface coating technology that exhibits both excellent hydrogen permeation

resistance and excellent wear resistance. There are many surface coating technologies with excellent hydrogen permeation resistance and wear resistance7,8. Among them, the diamond-like

carbon (DLC) coating is known to form a barrier layer with excellent hydrogen permeation resistance and wear resistance due to its inherent structure and characteristics9,10. In general, the

DLC coating consists of an amorphous carbon structure in which a graphite structure (sp2) and a diamond structure (sp3) are mixed, as well as in which the sp3 ratio is higher, so it is

called DLC coating11. In particular, the sp3 structure has a relatively dense structure due to the compressive residual stress. Therefore, it exhibits excellent hydrogen permeation

resistance and wear resistance12,13. In light of these advantages, researchers have investigated the hydrogen permeation resistance of DLC coatings. M. Tamura et al. investigated the

hydrogen barrier characteristic of DLC-coated stainless steel and reported that the DLC coating layer decreased hydrogen permeation into the stainless steel about 1000 times14. In

particular, they found that the hydrogen barrier function was improved when the chromium buffer layer was formed before the DLC coating process. In addition, G.A. Abbas et al. examined the

barrier performance of various DLC coatings, finding that the Si-doped hydrogenated amorphous DLC coating was associated with lower internal residual stress, decreased surface defects, and

improved barrier performance15. However, according to R. Lu et al., the DLC coating has a low diffusion coefficient for hydrogen but does not completely prevent hydrogen permeation16.

Moreover, T. Michler et al. reported that defects such as cracks and pinholes on the surface of the DLC coating act as pathways through which hydrogen can penetrate into the inside of the

coating17. According to C. Gu et al., when hydrogen permeates into the coating layer, the adhesion strength of the coating layer is degraded, and ultimately, the coating peels off18. Thus,

the DLC coating exhibits relatively good resistance to hydrogen permeation, but does not completely prevent hydrogen permeation. In particular, when the DLC coating is damaged due to a

decrease in its adhesion strength as a result of hydrogen permeation, its wear resistance decreases sharply due to the associated increase in the surface roughness and destruction of the DLC

coating layer. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the effect of hydrogen embrittlement on the adhesion strength and wear resistance of DLC coatings. In this research, DLC-coated

stainless steel was used to improve the hydrogen permeation resistance, as well as the adhesion strength and wear resistance, which was investigated by means of scratch and reciprocating

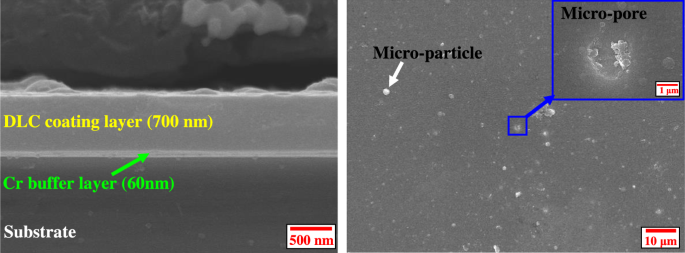

wear experiments after performing the hydrogen charging experiment on the DLC coating. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION CHARACTERISTICS OF DLC-COATED STAINLESS STEEL Figure 1 presents the

cross-section and surface analysis results of the DLC-coated stainless steel derived by FE-SEM. In this research, the DLC coating was deposited on the surface of the stainless steel by the

arc ion plating method, which entails relatively high ionization energy when compared with other physical vapor deposition (PVD) methods and enhances the adhesion strength of both the

coating layer and the substrate19. Generally, to improve the adhesion strength of the DLC coating, a very thin chromium buffer layer (about 60 nm) is deposited on the stainless steel

substrate using a chromium target (purity of 99.8%) in an argon environment, and then the DLC coating layer (about 700 nm) is deposited on the chromium buffer layer20,21. In particular, the

chromium buffer layer, which represents an interlayer between the DLC coating layer and the substrate, has been found to more effectively prevent hydrogen permeation14. As a result of the

cross-sectional observations, the chromium buffer layer and DLC coating layer were deposited densely and uniformly, and each interface was clearly observed. In addition, defects such as

cracks and pinholes were not found in the coating layer, buffer layer, and interface between the layers. By contrast, through the surface observations, micro-particles and pores of various

sizes were observed on the surface of the DLC coating. These micro-particles are formed during the coating process, and they are fragmented after colliding with other micro-particles,

forming defects such as pores and pinholes during the deposition process22. The micro-pores are formed approximately 2 μm in size, which is sufficiently large for molecular hydrogen (H2),

atomic hydrogen (H), and hydrogen ions (H+) to permeate and be trapped. In a hydrogen valve operating environment in which high-pressure hydrogen gas exists, hydrogen collides with

micro-particles to promote the formation of defects on the coating surface due to damage or delamination. According to Lee et al., mechanical characteristics are significantly reduced by

hydrogen permeation in the presence of defects such as pores and cracks on the surface of the metal rather than in the presence of dislocations inside the metal23. As a result,

micro-particles and micro-defects on the surface of the DLC coating are thought to be factors that accelerate both hydrogen attack and hydrogen embrittlement. Therefore, a critical task is

to reduce micro-particles and defects on the DLC coating surface and prevent substrate exposure. These can be achieved in three ways. The first is to completely remove the impurities inside

the chamber and on the surface of the substrate. In practice, however, it is very difficult to completely remove impurities. The second method is to increase the thickness of DLC coating.

The sizes of defects on DLC coating decrease with increasing coating thickness because of compressive residual stress24,25,26,27. However, as thickness increases, the residual stress also

rises at the same time, possibly reducing the durability of the coating layer and precluding the complete prevention of substrate exposure. The third approach is multilayer coating. When DLC

is deposited in multiple layers, the locations of the defects are staggered, which is thought to be more effective in preventing substrate exposure28. MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Figure 2

depicts the surface roughness measurement results of the DLC coating after the hydrogen charging experiments. Many researchers have conducted electrochemical hydrogen charging and

high-pressure hydrogen gaseous experiments to investigate the hydrogen embrittlement of materials exposed to hydrogen environments29,30. In addition, the current density corresponding to the

actual environments was investigated by comparing the experimental methods. In most research, however, electrochemical hydrogen charging and high-pressure gaseous experiments presented

different characteristics depending on the material31,32. In practice, the hydrogen gas pressure of approximately 24 bar reaches the hydrogen valve, which is the target of this study.

However, it is difficult to determine the current density corresponding to 24 bar in evaluating the durability of the valve. This research also is an accelerated experiment to investigate

damage to DLC coatings in the actual operating environments of hydrogen valves. After hydrogen charging experiment, the seven points of damaged specimen were measured using a 3D confocal

laser microscope, and after excluding the maximum and minimum values, a value approximated to the average and a 3D image were used. The measurements revealed the surface roughness of the DLC

coating without hydrogen charging to be about 0.269 μm. However, under the experimental conditions of the applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, 100 mA cm–2, and 150 mA cm–2, the surface

roughness was found to be about 0.382 μm, 0.628 μm, and 1.031 μm, respectively. In addition, the surface roughness of the DLC coating increased by up to 3.8 times as the applied current

density used for the hydrogen charging increased. This is considered to be due to damage and delamination of the DLC coating by hydrogen permeation. Figure 3 presents the degree of damage to

the DLC coating as the applied current density increases, using a 3D confocal laser microscope. In the case of an applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, a blister shape due to the hydrogen

blistering was observed on the surface of the DLC coating. In addition, micro-pinholes were observed in the center of the blister, and the chromium buffer layer was exposed. In particular,

the depth of the exposed part was about 0.71 μm (red color), which was fairly similar to the thickness of the DLC coating. At an applied current density of 100 mA cm–2, a crater shape was

observed, and the exposed area of the chrome buffer layer was larger due to the cracking and local delamination of the coating in the center of the crater. Moreover, damage to both the

buffer layer and the substrate due to hydrogen permeation appeared in the chromium buffer layer. The crater shape was formed by the advance of cracks at the interface between the buffer

layer and the substrate due to the hydrogen blistering and formation of the blister on the coating. When the elastic energy exceeds the fracture toughness of the DLC coating layer, the

coating layer is damaged and fractured33. With regard to an applied current density of 150 mA cm–2, the damage and delamination in relation to the DLC coating were more clearly observed, and

the exposed area of the chromium buffer layer was increased dramatically. In particular, in terms of the non-peeled off coating layer, a protrusion shape was observed at the edge of the

exposed buffer layer. This protrusion shape is considered to stem from the surface of the DLC coating being swollen due to hydrogen blistering or hydrogen-induced cracking caused by the

permeation and molecularization of hydrogen atoms into the interface between the DLC coating layer and chromium buffer layer. During this process, a micro-space is formed at the interface

between the DLC coating layer and chromium buffer layer, which causes a local decrease in the adhesion strength of the DLC coating. Thus, the blister and the protrusion shape formed on the

surface of the DLC coating increase the surface roughness of the coating, accelerate the damage and delamination caused to the DLC coating by external forces, and act as factors that

dramatically decrease the durability of the coating. On these bases, it is very important to prevent the initial permeation and damage to DLC coatings by hydrogen. In particular, DLC coating

is expected to remain durable if hydrogen permeation-induced blisters and protrusions are prevented from forming on its surface. Figure 4 depicts the results of the FE-SEM observations and

EDS analysis of the damaged and peeled off surface of the DLC coating following the hydrogen charging experiments. In the case of the DLC coating surface without hydrogen charging, only

micro-particles and micro-defects were observed, and the carbon components were mostly measured over the entire surface. However, damage and delamination were observed in relation to the DLC

coating after the hydrogen charging experiments, and the Fe and Cr components were clearly observed due to the exposure of the chromium buffer layer as the applied current density

increased. In addition, significant surface damage to the exposed chromium buffer layer was observed under the experimental conditions of applied current density of 100 mA cm–2 and higher.

When stainless steel is exposed due to the delamination of the DLC coating, hydrogen penetrates into its surface, causing cracks and damage to the surface of the substrate due to hydrogen

embrittlement34,35. In particular, under the experimental condition of an applied current density of 100 mA cm–2, multiple relatively small surface damages were found on the substrate.

However, in the case of an applied current density of 150 mA cm–2, relatively large surface damages were observed. The damage is thought to have grown into large damage through the

increasing and combining of the multiple small pieces of surface damage as the applied current density increased. In this way, as the size of the surface damage increases, the stress energy

is concentrated, degrading the mechanical characteristics and durability with even a small amount of external stress36,37. Figure 5 reveals the delamination ratio of the DLC coating layer

after the hydrogen charging, using Image J software. As a result of the calculations, the delamination ratio of the DLC coating with the applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, 100 mA cm–2,

and 150 mA cm–2 was 1.94%, 13.08%, and 58.28%, respectively. At an applied current density of 150 mA cm–2, the delamination ratio was the largest when compared with the other applied current

density. In general, the DLC coating layer exhibits excellent hydrogen permeation resistance. However, the delamination of the DLC coating is accelerated because the hydrogen permeation

resistance is rapidly reduced from the start point of damage and delamination with regard to the coating layer. Delaminated DLC coatings can migrate into a fuel cell and cause electrolyte

degradation. In severe cases, they can block hydrogen gas piping and valves, making it impossible to supply hydrogen gas to the fuel cell and thereby hindering the operation of the cell.

These results may be caused more significantly by hydrogen embrittlement or friction/wear of the material itself, not just the coating. Nevertheless, DLC coatings were chosen for this

research because of their relatively high resistance to hydrogen embrittlement and wear. In addition, the DLC coating is considered to have excellent performance as a thin film and will not

block the passage of hydrogen gas. Correspondingly, the initial damage and delamination of DLC coatings must be avoided to prevent hydrogen embrittlement. To summarize the findings depicted

in Figs. 3–5, the interfacial space between the DLC coating layer and chromium buffer layer is formed and expanded by hydrogen permeation, which is considered to be a factor that accelerates

the damage and delamination of the coating due to the decrease in the adhesion strength and the accumulation of elastic energy. ADHESION STRENGTH Figure 6 presents the results of the

scratch experiment performed to measure the adhesion strength of the DLC coating following the hydrogen charging. In the scratch experiment, the scratch tip was brought into contact with the

coating surface under a specific load, and then the coating surface was moved while the load was maintained or increased. This represents a practical method that can be used to evaluate the

adhesion strength of a coating by analyzing the acquired data (e.g., tip penetration depth, acoustic emission signal) and the shape of cracks formed on the coating surface by the scratches

using an optical microscope38. In particular, the adhesion strength is closely related to the durability of the coating39,40,41. Therefore, in this research, the adhesion strength of the DLC

coating according to the hydrogen charging was measured and evaluated quantitatively. To accomplish this, three critical loads measured through the scratch experiments were defined42,43.

The first critical load (Lc1) was the initiation of the initial cracking of the coating, the second critical load (Lc2) was the chipping caused by the coating cracking and partially

delaminating, and the third critical load (Lc3) was the complete destruction of the coating caused by the continuous and complete delamination (spalling). As shown in Fig. 6a, in the case of

the DLC coating without hydrogen charging, the first acoustic emission signal peak and the initial cracking of the coating were observed at an applied load of about 2.1 N (Lc1). Afterward,

the peak of the acoustic emission signal with the damage to the DLC coating was continuously measured as the applied load increased, and the initial and partial delamination of the coating

was observed at about 6.3 N (Lc2). Finally, spalling occurred along the scratch path due to the continuous and complete delamination of the coating at about 7.6 N (Lc3), indicating the

complete destruction of the coating. However, all the critical loads (Lc1, Lc2, and Lc3) decreased as the applied current density increased. When comparing the applied current density of 0

mA cm–2 and 150 mA cm–2, Lc1 presented a decrease of about 0.5 N; however, Lc2 and Lc3 decreased by 1.4 and 2.0 N, respectively. In particular, Lc2 indicated the largest decrease of about

0.9 N in the range of applied current density from 100 to 150 mA cm–2, although Lc3 decreased the most (to about 1 N) in the range of applied current density from 0 to 50 mA cm–2. Based on

these results, it can be seen that the hydrogen embrittlement had a great effect on the adhesion strength of the DLC coating. FRICTION AND WEAR BEHAVIOR Figure 7 depicts the friction

coefficients determined by the reciprocating friction experiment. Due to the nature of the experiment, the friction coefficients demonstrate positive and negative values depending on the

direction. However, the frictional forces of the material can be evaluated and compared with each other based on the width of the friction coefficients. As illustrated in Fig. 7a, the DLC

coating without hydrogen charging reached a friction coefficient of 0.6 μ as the substrate was exposed at about 488 m of sliding distance. However, with the increasing applied current

density of 50 mA cm–2, 100 mA cm–2, and 150 mA cm–2, the sliding distance decreased to 430 m, 339 m, and 295 m, respectively. The largest decrease of about 91 m was observed under the

experimental conditions of applied current density of 50–100 mA cm–2. It is thought that the coating was peeled off in a shorter period of time due to the decrease in the durability of the

coating caused by the hydrogen embrittlement. To analyze the change in the friction coefficient with the sliding distance in more detail, the graph of Fig. 7a was enlarged and exhibited as

in Fig. 7b. In addition, the width of the friction coefficient was divided into three parts to obtain the initial friction coefficient width (μ1), the intermediate friction coefficient width

(μ2), and final friction coefficient width (μ3), which were compared. At 0 mA cm–2, the μ1 was measured as about 0.169 μ, which was relatively low. In general, DLC coatings exhibit high

hardness, excellent thermal stability, smooth surface, and self-lubricating (solid lubricating) characteristics, which result in excellent wear resistance44,45,46,47,48. In particular, DLC

coatings have a very low friction coefficient, which minimizes the generation of the frictional heat that causes wear damage and provides excellent wear resistance because the adhesive force

between the contact surfaces is relatively low49,50. In terms of the friction experiment results, the friction coefficient of the DLC coating without hydrogen charging was about 0.085 μ

(half of the μ1 of 0.169 μ), indicating a low friction coefficient and excellent wear resistance. However, as the sliding distance increased, the width of the friction coefficient also

increased. This increase in the width of the friction coefficient with the increasing sliding distance indicated a similar trend under all the experimental conditions. However, for the

applied current density of 100 mA cm–2 and 150 mA cm–2, the width of friction coefficient presented almost similar values for μ1, μ2, and μ3. In addition, in the case of μ1, the friction

coefficient presented a relatively large increase according to the increase in the applied current density. However, μ3 presented almost similar values under all the experimental conditions.

In particular, when comparing the applied current density of 0 mA cm–2 and 50 mA cm–2 with hydrogen charging, μ1 increased by about 0.02 μ. In this way, while the effect of hydrogen

permeation in the coating is relatively small, it can have a large effect on the wear resistance of the coating. Moreover, when the DLC coating is partially damaged or peeled off, the wear

resistance function of the coating is lost and the durability of both the coating layer and the substrate is rapidly reduced. Figures 8 and 9 present 3D images of the wear tracks and the

measurement results of the depth and width of the wear damage observed using a 3D confocal laser microscope. In general, wear products (wear debris, wear particles, etc.) are generated by

the work hardening and phase transformation of the contact surface that occurs during friction experiments, which accumulate at the edge of the wear track to form a ridge51. This shape is

one of the main factors that accelerate wear damage, as plasticized parts are peeled off by frictional wear52. However, in the case of the DLC coating used in this research, a ridge shape

caused by the wear products was not observed. This is thought to be because the surface is not plasticized due to the wear characteristics of the DLC coating, and as a result, no wear

products are formed. In addition, the frictional heat is relatively low, so the tendency toward abrasive wear was more dominant than that toward adhesive wear53,54. As demonstrated in Fig.

9a, the wear depth of the DLC coating without hydrogen charging presented a wear depth of about 11.18 μm, while the increasing applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, 100 mA cm–2, and 150 mA

cm–2 resulted in wear depths of 10.63 μm, 9.83 μm, and 9.17 μm, respectively. As the result, the wear depth presented a decreasing trend as the applied current density increased. In this

research, to improve the adhesion strength of the DLC coating on the stainless steel, a chromium buffer layer of 60 nm in thickness was first deposited on the stainless steel and then the

DLC coating was deposited, meaning that the adhesion strength of the coating was relatively excellent. In general, the coating layer is worn by shear force during friction experiments55. In

particular, when the DLC coating thickness is reduced by wear, the compressive residual stress and adhesion strength of the coating are both reduced56,57. At the same time, when a shear

force stronger than the compressive residual stress and adhesion strength of the coating is applied, the interface destruction between the coating and substrate is accelerated, resulting in

damage and delamination of the coating58. According to A. A. Voevodin et al., when a contact load is applied to the coating layer with the wear resistance, the strongest shear force is

distributed at the interface between the coating and substrate59. When the coating thickness is relatively thin, the shear force and frictional heat act more strongly on the substrate to

plastically deform it, ultimately causing the adhesion failure of the coating60,61,62,63. Therefore, when a strong shear force is applied while a certain adhesion strength is retained due to

the wear of the coating, the coating is peeled off and the buffer layer or substrate is plasticized and eventually detached, resulting in adhesive wear64. This tendency is reflected in the

results of this research. However, as described in Fig. 9b, the wear width exhibited a tendency to increase with an increasing applied current density. In particular, the exposed width of

the 316 L stainless steel presented a relatively large increase with an increasing applied current density. The exposed width of the substrate at the applied current density of 0 mA cm–2 and

150 mA cm–2 was 74.21 μm and 302.12 μm, respectively, which indicated a more than 4 times increase. This is thought to be because the adhesion strength of DLC coating layer and the chromium

buffer layer is locally lowered by hydrogen permeation. As a result, the exposed width of the substrate is increased due to partial or complete delamination of the coating by wear damage in

a relatively wide range. These results are considered to be due to the following causes. First, the adhesion strength of the DLC coating layer and the chromium buffer layer is locally

lowered by hydrogen permeation. Afterward, the coating is partially or completely peeled off by friction to increase the exposed width of the substrate. Figure 10 depicts the results of the

FE-SEM observations and EDS analysis of the damaged surface by wear of the DLC coating. In terms of the worn surface of the DLC coating without the hydrogen charging, abrasive wear was

evident in the area where the DLC coating layer remained (i.e., the outer part of the wear track). By contrast, the central part where the substrate was exposed presented damage due to

adhesive wear. As mentioned above, the DLC coating has a low friction coefficient, high thermal stability, smooth surface finish, and self-lubricating characteristics that prevent adhesion

at the interface between the two materials. In other words, as the DLC coating exhibits excellent adhesion resistance, abrasive wear is considered to be dominant65. Conversely, the stainless

steel has a relatively high friction coefficient and low thermal stability, meaning that adhesion between the two contact materials is easy, which results in adhesive wear due to the shear

force66,67. However, the surface observation results after friction experiment in this research present adhesive wear due to the adhesion strength of the DLC coating and the substrate. In

general, DLC coatings are subject to abrasive wear due to the specific shear force. However, when the thickness of the coating is thinner than the critical value, it cannot tolerate the

applied shear force. As a consequence, it is thought that the part of the substrate bonded to the coating layer is peeled off. Thus, the DLC coating exhibits resistance to shear force for

even a very thin film of 0.7 µm, and it also exhibits excellent wear resistance. However, when the thickness is reduced as a result of wear to the coating layer, it is considered that the

resistance to shear force is lost and the DLC coating exhibits characteristics such as adhesive wear. In the case of the DLC coating with hydrogen charging, the exposed area of the substrate

increased. With regard to the applied current density of 100 mA cm–2 and 150 mA cm–2 when compared with 50 mA cm–2, multiple instances of micro local delamination were observed. In

addition, in the case of an applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, wear products such as wear debris were not observed on the surface of the DLC coating. However, plastically deformed parts

appeared in the exposed substrate due to the friction between the substrate and the alumina balls, and wear debris of various sizes were observed. The plastic deformation of the substrate

and the formation of wear debris were more clearly observed at the applied current density of 100 mA cm–2 and 150 mA cm–2. In the case of an applied current density of 100 mA cm–2, cracks in

the plastically deformed part first occurred in the exposed substrate, and in severe cases, these cracks were converted into wear debris. These wear debris are formed by the plastic

deformation of the metal and the cracks of surface. In addition, the wear debris increases the surface roughness and acts as a factor that lowers wear resistance. However, the DLC coating

did not form wear products. In addition, it is thought that excellent wear resistance can be continuously maintained by the remaining DLC coating layer even if the adhesion strength of the

coating is reduced and local delamination occurs due to hydrogen charging. DELAMINATION MECHANISM OF DLC COATING LAYER Figure 11 illustrates the delamination mechanism of the DLC coating

associated with hydrogen charging. Initially, there are micro-cracks and micro-pores on the surface of the DLC coating (1st step). Simultaneously, hydrogen atoms in the hydrogen environment

penetrate and diffuse into the interface between the DLC coating layer and chromium buffer layer through the micro-cracks or micro-pores (2nd step). Thereafter, the diffused hydrogen atoms

are molecularized to cause the hydrogen blistering. Therefore, the size of the interface region is expanded by vertical stress and a micro-space is formed, thereby decreasing the adhesion

strength between the DLC coating layer and the chromium buffer layer (3rd step). During this third step, the degradation of the DLC coating layer is initiated. In addition, the micro-cracks

and the blister shapes appear on the surface of the DLC coating by the buckling of the coating layer. Hence, when more hydrogen molecules are generated at the interface between the DLC

coating layer and chromium buffer layer, stronger vertical stress acts on the upper surface of the DLC coating layer to cause the growth of the blister on the surface of the coating. In

addition, interfacial cracking between the coating layer and buffer layer is promoted. Furthermore, the adhesion strength is almost lost (4th step). If this process has continued, elastic

energy exceeding the fracture toughness is accumulated in the DLC coating, and the cracking of the coating layer progresses further. In severe cases, micro-pinholes are formed due to the

destruction of the coating layer, and the chromium buffer layer is exposed (5th step). Moreover, as the adhesion strength decreases and is lost in the horizontal direction of the formed

pinholes, a crater shape appears due to the local delamination of the DLC coating, and finally, the coating layer completely peels off (6th step). CONSIDERATIONS FOR APPLICATION OF DLC

COATING TO PREVENT HYDROGEN EMBRITTLEMENT This research examined the resistance of hydrogen embrittlement resistance and wear of DLC coatings to improve the durability of hydrogen valves as

components of hydrogen vehicles. In future work, we intend to address the following issues: The first is hydrogen embrittlement on a substrate during glow discharge in a mixed environment of

argon and hydrogen gas during DLC coating process. Many researchers have argued that surface coating technology is required in a hydrogen gas-free environment due to the problem of hydrogen

embrittlement during glow discharge68,69. However, some studies have found no hydrogen embrittlement characteristics in substrates exposed to a mixed environment of hydrogen gas70,71. The

second issue is the change in the characteristics of DLC coatings due to hydrogen embrittlement. DLC coatings have a combined diamond (sp3) and graphite (sp2) structure, and they exhibit

different binding energies depending on the fractions of sp3 and sp2 in the coatings72. In particular, under abundant sp3, DLC coating has a dense structure and effectively prevents the

migration of substances73,74. Correspondingly, the binding energies and characteristics of DLC coatings are expected to change because of hydrogen embrittlement. It is therefore necessary to

investigate the effects of hydrogen on the crystallographic structure of DLC coating. The third issue for future exploration is that the exposure area of a specimen differs from that of an

actual component. In this research, it was necessary to consider the specimen affected by hydrogen and the exposure area of an actual hydrogen valve. However, the error ratio determined by

differences in specimen sizes was expected to be small because the experiment was performed under current density. The fourth issue to be addressed in future work is how to effectively

prevent hydrogen embrittlement and damage in DLC coatings. As shown in this research, DLC coatings exhibit excellent resistance against hydrogen permeation. However, H2, H, and H+ can

permeate through surface defects to the interface between the DLC coating layer and the buffer layer or substrate. This problem can be solved by increasing the thickness of DLC coating or

performing multilayer deposition. The challenge is that increasing the thickness of DLC coating diminishes the durability of the coating layer because of increased residual stress. This

phenomenon can produce internal cracks, which can increase the permeation ratio of hydrogen gas75. In addition, hydrogenated DLC coatings suffer from various shortcomings, such as poor

adhesion to a substrate, limited thickness, the desorption of hydrogen over time, and temperature changes76,77,78. Nevertheless, the multilayer deposition of DLC coatings can increase

thickness while simultaneously distributing residual stresses to each layer79,80. Surface defects can also be staggered layer by layer to minimize substrate exposure81. Therefore, multilayer

deposition is considered the optimal coating method, as it presents the strongest resistance against hydrogen embrittlement. Previous research has found significantly better hydrogen

embrittlement resistance by DLC coatings than CrN coatings82. In particular, DLC coatings on hydrogen valves that reciprocate for more than approximately twice per second exhibit a

significantly lower friction coefficient and are recommended for hydrogen valve applications due to their excellent wear resistance. However, future research on buffer layer materials

(deposition force, hydrogen permeation resistance, etc.) is needed depending on type of substrate. As a result, the DLC coating prevented hydrogen permeation into the substrate and exhibited

relatively excellent wear resistance, indicating it to be a surface coating technology that is suitable for use in parts where frictional wear occurs while hydrogen exists. However, the DLC

coating could not completely prevent hydrogen permeation, and when hydrogen penetrated into the interface between the coating layer and buffer layer or substrate, the durability of the DLC

coating was reduced due to hydrogen molecularization. We recommend the DLC coating technology for plunger, which is the component of hydrogen valve. This is due to the excellent hydrogen

embrittlement resistance and wear resistance of DLC coatings. In particular, DLC coatings exhibit improved performance when surface defects are controlled, when buffer layer materials are

used, and when the application environment is considered during deposition. Further research should be directed toward the application of DLC coatings under various conditions. METHODS

PREPARATION OF SPECIMEN AND DLC COATING The specimen used in this research was 316 L stainless steel and the chemical composition of the stainless steel is depicted in Table 1. To perform

the DLC coating process, the specimen was cut to a size of 20 mm × 20 mm and its surface was polished using 4000 grit SiC abrasive paper and 0.3 μm alumina suspension. The polished specimen

was then cleaned with ultrasonic waves using acetone and distilled water before being dried in a vacuum dryer for 24 h. Subsequently, an amorphous DLC coating was deposited on the stainless

steel surface using the arc ion plating method. Chamber pressure and temperature were maintained at 3 × 10–5 Torr and 350 °C, respectively, for 60 min to remove the residual gas and moisture

inside the chamber. Argon and hydrogen gas were then injected into the chamber at a ratio of 66:34, and the substrate was glow-discharged for 40 min by applying a bias of 400 to 500 V. The

plasma generated in this process ionizes argon and hydrogen gas, thereby removing impurities from the substrate surface and activating it. In this case, hydrogen ions can penetrate the

surface of the substrate and give rise to the risk of hydrogen embrittlement. However, according to J. Cwiek, no difference in elongation is found in tensile tests performed with and without

hydrogen gas during glow discharge70. Furthermore, in the current research, the substrate was exposed to hydrogen for 40 min at a flow rate of 34 sccm, which is a negligible value that is

not expected to cause hydrogen embrittlement. After surface cleaning through glow discharge, a chromium buffer layer was deposited onto the surface to improve the adhesion strength of the

DLC coating layer. Deposition of the buffer layer was performed in an environment injected with argon at 100 sccm (temperature: 350 °C, pressure: 2.5 × 10–3 Torr) for 2 min. Amorphous DLC

coating was then deposited onto the specimen surface via carbon etching and carbon coating. Carbon etching during glow discharge is a preliminary step in improving the deposition performance

of DLC coatings. The detailed parameters of the process are shown in Table 2. HYDROGEN CHARGING EXPERIMENT To investigate the hydrogen permeation resistance of the DLC-coated stainless

steel, hydrogen was artificially charged for 12 h at applied current density of 50 mA cm–2, 100 mA cm–2, and 150 mA cm–2 in 2 N H2SO4 + 1 g L–1 Na2HAsO4 · 7H2O solution using a power supply.

Direct current was applied to the DLC-coated specimen (working electrode) as the cathode and the platinum electrode (counter electrode) as the anode. Details are shown in the schematic in

Fig. 12. After the hydrogen charging, the surface of the specimen was observed and the surface roughness (Sa) was measured using a three-dimensional (3D) confocal laser microscope (OLS-5000,

OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, the effect of the hydrogen embrittlement on the DLC coating layer was analyzed by means of field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM,

JSM-7500F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, AZTec Energy, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) analyses. Moreover, the delamination ratio of the DLC coating

was measured using Image J software. SCRATCH EXPERIMENT To measure the adhesion strength of the DLC coating before and after the hydrogen charging, a micro scratch tester (MCT3, Anton Paar,

Garz, Austria) equipped with an optical microscope, an acoustic emission detection system, a tangential friction force sensor, and a penetration depth measurement sensor were used. For the

scratch experiment, a Rockwell C diamond indenter with an angle of 120° and a diameter of 100 μm was used. The scratch distance was 2 mm, the load increased linearly from 0.02 N to 10 N, and

the scratch rate and load rate were set at 0.5 mm min–1 and 2.5 N min–1, respectively. In addition, to ensure reproducibility, the scratch experiment was repeated 14 times under the same

conditions. The scratch data were approximated to the average and the results of the optical microscope observations were analyzed. FRICTION EXPERIMENT A friction experiment was conducted to

evaluate the frictional wear characteristics of the DLC-coated stainless steel following the hydrogen charging. A tribometer (TRB3, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) was used for the friction

experiment, and a ball-on-disk method was adopted. In addition, to simulate the operating environment of the hydrogen valve, the friction coefficient and sliding distance were measured after

the reciprocating wear experiment. The ball used in the experiment was an alumina ball with a diameter of 6 mm and a Vickers hardness of 1650 HV. In terms of the experimental conditions,

the rotation radius, reciprocating angle, sliding speed, and applied load of the disk were set as 6 mm, 30°, 3 cm s–1, and 25 N, respectively, while the air temperature and humidity were

maintained at 25 °C and 30%, respectively. In addition, to evaluate the durability of the DLC coating layer according to the hydrogen charging, the friction experiment was set to stop when

the friction coefficient reached 0.6 μ, and the associations between the sliding distance and the hydrogen charging time were compared. After the experiment, the wear depth, width, and

surface roughness of the wear track were measured using a 3D confocal laser microscope to evaluate the wear damage. Furthermore, the worn surface was observed and the chemical composition

was analyzed by means of FE-SEM and EDS. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, and any additional data that support the

findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Sekoai, P. T. & Yoro, K. O. Biofuel development initiatives in Sub-Saharan

Africa: opportunities and challenges. _Climate_ 4, 33 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Luo, Y. et al. Development and application of fuel cells in the automobile industry. _J. Energy

Storage_ 42, 103124 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Olabi, A. G., Wilberforce, T. & Abdelkareem, M. A. Fuel cell application in the automotive industry and future perspective.

_Energy_ 214, 118955 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Pei, P. & Chen, H. Main factors affecting the lifetime of Proton Exchange Membrane fuel cells in vehicle applications: a review.

_Appl. Energy_ 125, 60–75 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Hwang, H. K., Shin, D. H. & Kim, S. J. Hydrogen embrittlement characteristics by slow strain rate test of aluminum alloy for

hydrogen valve of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle. _Corros. Sci. Technol._ 21, 503–513 (2022). CAS Google Scholar * Seo, D. I. & Lee, J. B. Comparison of hydrogen embrittlement resistance

between 2205 duplex stainless steels and type 316L austenitic stainless steels under the cathodic applied potential. _Corros. Sci. Technol._ 15, 237–244 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Rönnebro, E. C. E., Oelrich, R. L. & Gates, R. O. Recent advances and prospects in design of hydrogen permeation barrier materials for energy applications—a review. _Molecules_ 27,

6528 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Laadel, N. E., El Mansori, M., Kang, N., Marlin, S. & Boussant-Roux, Y. Permeation barriers for hydrogen embrittlement

prevention in metals—a review on mechanisms, materials suitability and efficiency. _Int. J. Hydrog. Energy_ 47, 32707–32731 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hatta, A., Kaneko, S.

& Hassan, M. K. Hydrogen permeation through diamond-like carbon thin films coated on PET sheet. _Plasma Process. Polym._ 4, 241–244 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Lin, Y., Zhou, Z.

& Li, K. Y. Improved wear resistance at high contact stresses of hydrogen-free diamond-like carbon coatings by carbon/carbon multilayer architecture. _Appl. Surf. Sci._ 477, 137–146

(2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kim, S. H. & Jang, J. C. Investigation of structural change of DLC coating during frictional wear by Raman spectroscopy. _J. Korean Inst. Surf.

Eng._ 52, 16–22 (2019). CAS Google Scholar * Park, M. S., Kim, D. Y., Shin, C. S. & Kim, W. R. Improved adhesion of DLC films by using a nitriding layer on AISI H13 substrate. _J.

Korean Inst. Surf. Eng._ 54, 307–314 (2021). CAS Google Scholar * Liechtenstein, V. K., Ivkova, T. M., Spitsyn, A. V. & Olshanski, E. D. A study of very thin DLC foils as a gas

barrier. _Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip._ 590, 171–175 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tamura, M. & Kumagai, T. Hydrogen

permeability of diamondlike amorphous carbons. _J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film._ 35, 04D101 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Abbas, G. A., McLaughlin, J. A. & Harkin-Jones, E.

A study of ta-C, a-C:H and Si-a:C:H thin films on polymer substrates as a gas barrier. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 13, 1342–1345 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lu, R. et al. Effect of

diamond-like carbon coating on preventing the ingress of hydrogen into bearing steel. _Tribol. Trans._ 64, 157–166 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Michler, T. & Naumann, J.

Coatings to reduce hydrogen environment embrittlement of 304 austenitic stainless steel. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 203, 1819–1828 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gu, C., Hu, J. &

Zhong, X. The coating delamination mitigation of epoxy coatings by inhibiting the hydrogen evolution reaction. _Prog. Org. Coat._ 147, 105774 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shi, C.

M., Wang, T. G., Pei, Z. L., Gong, J. & Sun, C. Effects of the thickness ratio of CrN vs Cr2O3 layer on the properties of double-layered CrN/Cr2O3 coatings deposited by arc ion plating.

_J. Mater. Sci. Technol._ 30, 473–479 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ahmad, I. et al. Substrate effects on the microstructure of hydrogenated amorphous carbon films. _Curr. Appl.

Phys._ 9, 937–942 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Song, J. S. & Nam, T. W. The effects of imterlayer on the DLC coating. _Corros. Sci. Technol._ 10, 65–70 (2011). Google Scholar *

Boxman, R. L. & Goldsmith, S. Macroparticle contamination in cathodic arc coatings: generation, transport and control. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 52, 39–50 (1992). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Guan, X. et al. Microstructures and properties of Zr/CrN multilayer coatings fabricated by multi-arc ion plating. _Tribol. Int._ 106, 78–87 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Shin, D. H. & Kim, S. J. Electrochemical characteristics and damage behaviour of DLC-coated 316L stainless steel for metallic bipolar plates of PEMFCs. _Trans. Imf._ 101, 308–319

(2023). Article Google Scholar * Gunnars, J. & Alahelisten, A. Thermal stresses in diamond coatings and their influence on coating wear and failure. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 80, 303–312

(1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pauleau, Y. Residual stresses in DLC films and adhesion to various substrates. In:Donnet, C., Erdemir, A. (eds) Tribology of Diamond-Like Carbon

Films. p. 102–136 (Springer, 2008). * Yi, P., Zhang, D., Peng, L. & Lai, X. Impact of film thickness on defects and the graphitization of nanothin carbon coatings used for metallic

bipolar plates in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. _ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces_ 10, 34561–34572 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dalibon, E. L., Moreira, R. D., Guitar,

M. A., Trava-Airoldi, V. J. & Brühl, S. P. Influence of the substrate pre-treatment on the mechanical and corrosion response of multilayer DLC coatings. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 118, 108507

(2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Arniella, V., Zafra, A., Álvarez, G., Belzunce, J. & Rodríguez, C. Comparative study of embrittlement of quenched and tempered steels in hydrogen

environments. _Int. J. Hydrog. Energy_ 47, 17056–17068 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * Okonkwo, P. C. et al. A focused review of the hydrogen storage tank embrittlement mechanism

process. _Int. J. Hydrog. Energy_ 48, 12935–12948 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Djukic, M. B., Bakic, G. M., Zeravcic, V. S. & Sedmak, A. The synergistic action and interplay

of hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms in steels and iron: Localized plasticity and decohesion. _Eng. Fract. Mech._ 216, 106528 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Koren, E. et al. Experimental

comparison of gaseous and electrochemical hydrogen charging in X65 pipeline steel using the permeation technique. _Corros. Sci._ 215, 111025 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Falub,

C. V. et al. In vitro studies of the adhesion of diamond-like carbon thin films on CoCrMo biomedical implant alloy. _Acta Mater._ 59, 4678–4689 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Elhoud, A. M., Renton, N. C. & Deans, W. F. Hydrogen embrittlement of super duplex stainless steel in acid solution. _Int. J. Hydrog. Energy_ 35, 6455–6464 (2010). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Murakami, Y., Kanezaki, T. & Mine, Y. Hydrogen effect against hydrogen embrittlement. _Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci._ 41, 2548–2562 (2010). Article Google

Scholar * Wang, S., Liang, W., Duan, L., Li, G. & Cui, J. Effects of loading rates on mechanical property and failure behavior of single-lap adhesive joints with carbon fiber

reinforced plastics and aluminum alloys. _Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol._ 106, 2569–2581 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Li, B., Shen, Y. & Hu, W. Casting defects induced fatigue damage

in aircraft frames of ZL205A aluminum alloy—a failure analysis. _Mater. Des._ 32, 2570–2582 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ollendorf, H. & Schneider, D. A comparative study of

adhesion test methods for hard coatings. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 113, 86–102 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Łępicka, M., Grądzka-Dahlke, M., Pieniak, D., Pasierbiewicz, K. &

Niewczas, A. Effect of mechanical properties of substrate and coating on wear performance of TiN- or DLC-coated 316LVM stainless steel. _Wear_ 382–383, 62–70 (2017). Article Google Scholar

* Shin, D. H. & Kim, S. J. Effect of hydrogen charging on the mechanical characteristics and coating layer of CrN-coated aluminum alloy for light-weight FCEVs. _Jpn J. Appl. Phys._ 62,

1–10 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Zaidi, H., Djamai, A., Chin, K. J. & Mathia, T. Characterisation of DLC coating adherence by scratch testing. _Tribol. Int._ 39, 124–128 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Waseem, B. et al. _Optimization and Characterization of Adhesion Properties of DLC Coatings on Different Substrates_. _Materials Today: Proceedings_ 2

(Elsevier Ltd., 2015). * Jacobs, R. et al. A certified reference material for the scratch test. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 174–175, 1008–1013 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Tyagi, A. et al.

A critical review of diamond like carbon coating for wear resistance applications. _Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater._ 78, 107–122 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Erdemir, A. &

Martin, J. M. Superior wear resistance of diamond and DLC coatings. _Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci._ 22, 243–254 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, L., Wan, S., Wang, S. C.,

Wood, R. J. K. & Xue, Q. J. Gradient DLC-based nanocomposite coatings as a solution to improve tribological performance of aluminum alloy. _Tribol. Lett._ 38, 155–160 (2010). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Vanhulsel, A. et al. DLC solid lubricant coatings on ball bearings for space applications. _Tribol. Int._ 40, 1186–1194 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Scharf,

T. W. & Prasad, S. V. Solid lubricants: a review. _J. Mater. Sci._ 48, 511–531 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fontaine, J., Donnet, C. & Erdemir, A. Fundamentals of the

tribology of DLC coatings. _Tribol. Diamond-Like Carbon Film. Fundam. Appl_. 139–154 (2008). * Fukui, H., Okida, J., Omori, N., Moriguchi, H. & Tsuda, K. Cutting performance of DLC

coated tools in dry machining aluminum alloys. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 187, 70–76 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rao, R. N. & Das, S. Effect of matrix alloy and influence of SiC

particle on the sliding wear characteristics of aluminium alloy composites. _Mater. Des._ 31, 1200–1207 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mekicha, M. A. et al. Study of wear particles

formation at single asperity contact: an experimental and numerical approach. _Wear_ 470–471, 203644 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Harris, S. J., Weiner, A. M. & Meng, W. J.

Tribology of metal-containing diamond-like carbon coatings. _Wear_ 211, 208–217 (1997). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhou, Z. F., Li, K. Y., Bello, I., Lee, C. S. & Lee, S. T. Study

of tribological performance of ECR-CVD diamond-like carbon coatings on steel substrates Part 2. The analysis of wear mechanism. _Wear_ 258, 1589–1599 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Kato, K. Wear in relation to friction—a review. _Wear_ 241, 151–157 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xiao, Y., Shi, W., Han, Z., Luo, J. & Xu, L. Residual stress and its effect on

failure in a DLC coating on a steel substrate with rough surfaces. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 66, 23–35 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sheeja, D., Tay, B. K., Leong, K. W. & Lee, C.

H. Effect of film thickness on the stress and adhesion of diamond-like carbon coatings. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 11, 1643–1647 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Escudeiro, A., Wimmer, M.

A., Polcar, T. & Cavaleiro, A. Tribological behavior of uncoated and DLC-coated CoCr and Ti-alloys in contact with UHMWPE and PEEK counterbodies. _Tribol. Int._ 89, 97–104 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Voevodin, A. A., Iarve, E. V., Ragland, W., Zabinski, J. S. & Donaldson, S. Stress analyses and in-situ fracture observation of wear protective multilayer

coatings in contact loading. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 148, 38–45 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bernoulli, D. et al. Improved contact damage resistance of hydrogenated diamond-like

carbon (DLC) with a ductile α-Ta interlayer. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 58, 78–83 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bernoulli, D. et al. Contact damage of hard and brittle thin films on

ductile metallic substrates: an analysis of diamond-like carbon on titanium substrates. _J. Mater. Sci._ 50, 2779–2787 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bernoulli, D. et al. Cohesive

and adhesive failure of hard and brittle films on ductile metallic substrates: A film thickness size effect analysis of the model system hydrogenated diamond-like carbon (a-C:H) on Ti

substrates. _Acta Mater._ 83, 29–36 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Okonkwo, P. C., Kelly, G., Rolfe, B. F. & Pereira, M. P. The effect of sliding speed on the wear of steel-tool

steel pairs. _Tribol. Int._ 97, 218–227 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Zhou, Y. et al. Hardness anomaly, plastic deformation work and fretting wear properties of polycrystalline TiN/CrN

multilayers. _Wear_ 236, 159–164 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sui, X., Liu, J., Zhang, S., Yang, J. & Hao, J. Microstructure, mechanical and tribological characterization of

CrN/DLC/Cr-DLC multilayer coating with improved adhesive wear resistance. _Appl. Surf. Sci._ 439, 24–32 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gaard, A., Hallbäck, N., Krakhmalev, P. &

Bergström, J. Temperature effects on adhesive wear in dry sliding contacts. _Wear_ 268, 968–975 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wei, M. X., Wang, S. Q., Wang, L. & Cui, X. H.

Wear and friction characteristics of a selected stainless steel. _Tribol. Trans._ 54, 840–848 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mashovets, N. S., Pastukh, I. M. & Voloshko, S. M.

Aspects of the practical application of titanium alloys after low temperature nitriding glow discharge in hydrogen-free-gas media. _Appl. Surf. Sci._ 392, 356–361 (2017). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Konno, T. et al. Characterization of carburized layer on low-alloy steel fabricated by hydrogen-free carburizing process using carbon ions. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 135,

109816 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cwiek, J. Hydrogen degradation of high-strength steels. _J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf._ 37, 193–212 (2009). Google Scholar * Shin, D. H. & Kim,

S. J. Effects of hard anodizing and plasma ion-nitriding on Al alloy for hydrogen embrittlement protection. _Corros. Sci. Technol._ 22, 221–231 (2023). CAS Google Scholar * Mabuchi, Y.,

Higuchi, T. & Weihnacht, V. Effect of sp2/sp3 bonding ratio and nitrogen content on friction properties of hydrogen-free DLC coatings. _Tribol. Int._ 62, 130–140 (2013). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Park, H. et al. The influence of hydrogen concentration in amorphous carbon films on mechanical properties and fluorine penetration: A density functional theory and: ab

initio molecular dynamics study. _RSC Adv._ 10, 6822–6830 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, L., Lu, F., Tian, J., Xia, S. & Diao, Y. Electronic and

optical properties of amorphous carbon with different sp3/sp2 hybridization ratio. _Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process._ 125, 1–10 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Dorner, A. et al.

Diamond-like carbon-coated Ti6A14V: influence of the coating thickness on the structure and the abrasive wear resistance. _Wear_ 249, 489–497 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Vasquez-Borucki, S., Jacob, W. & Achete, C. A. Amorphous hydrogenated carbon films as barrier for gas permeation through polymer films. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 9, 1971–1978 (2000). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Capote, G., Bonetti, L. F., Santos, L. V., Trava-Airoldi, V. J. & Corat, E. J. Adherent amorphous hydrogenated carbon films on metals deposited by plasma

enhanced chemical vapor deposition. _Thin Solid Films_ 516, 4011–4017 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Akasaka, H. et al. Thermal decomposition and structural variation by heating on

hydrogenated amorphous carbon films. _Diam. Relat. Mater._ 101, 107609 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lara, L. C., Costa, H. & De Mello, J. D. B. Influence of layer thickness on

sliding wear of multifunctional tribological coatings. _Ind. Lubr. Tribol._ 67, 460–467 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Djabella, H. & Arnell, R. D. Finite element comparative study

of elastic stresses in single, double layer and multilayered coated systems. _Thin Solid Films_ 235, 156–162 (1993). Article Google Scholar * Mingge, W., Congda, L., Tao, H., Guohai, C.

& Donghui, W. Chromium interlayer amorphous carbon film for 304 stainless steel bipolar plate of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. _Surf. Coat. Technol._ 307, 374–381 (2016). Article

Google Scholar * Shin, D. H. & Kim, S. J. Effect of hydrogen charging on the mechanical characteristics and coating layer of CrN-coated aluminum alloy for light-weight FCEVs. _Jpn J.

Appl. Phys._ 62, SN1004 (2023). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Advanced Reliability Engineering for Automotive Electronics based

on Bigdata Technique Infra (P0021563: Development of Lightweight Hydrogen Valve Module), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE), Republic of Korea. AUTHOR

INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Marine Engineering, Graduate School, Mokpo National Maritime University, 91, Haeyangdaehak-ro, Mokpo-si, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea

Dong-Ho Shin * Division of Marine System Engineering, Mokpo National Maritime University, 91, Haeyangdaehak-ro, Mokpo-si, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea Seong-Jong Kim Authors * Dong-Ho

Shin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Seong-Jong Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Dong-Ho Shin: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, validation, writing—original draft. Seong-Jong Kim: Conceptualization, formal analysis,

funding acquisition, writing—reviewing & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Seong-Jong Kim. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING

INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Shin, DH., Kim, SJ. Effect of hydrogen embrittlement on mechanical characteristics of DLC-coating for hydrogen valves of FCEVs. _npj Mater Degrad_ 8, 47

(2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00460-y Download citation * Received: 25 December 2023 * Accepted: 10 April 2024 * Published: 04 May 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00460-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative