Latent virus reactivation in astronauts on the international space station

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Reactivation of latent herpes viruses was measured in 23 astronauts (18 male and 5 female) before, during, and after long-duration (up to 180 days) spaceflight onboard the

international space station . Twenty age-matched and sex-matched healthy ground-based subjects were included as a control group. Blood, urine, and saliva samples were collected before,

during, and after spaceflight. Saliva was analyzed for Epstein–Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, and herpes simplex virus type 1. Urine was analyzed for cytomegalovirus. One astronaut did

not shed any targeted virus in samples collected during the three mission phases. Shedding of Epstein–Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus was detected in 8 of the 23

astronauts. These viruses reactivated independently of each other. Reactivation of Epstein–Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus increased in frequency, duration, and

amplitude (viral copy numbers) when compared to short duration (10 to 16 days) space shuttle missions. No evidence of reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type

2, or human herpes virus 6 was found. The mean diurnal trajectory of salivary cortisol changed significantly during flight as compared to before flight (_P_ = 0.010). There was no

statistically significant difference in levels of plasma cortisol or dehydoepiandosterone concentrations among time points before, during, and after flight for these international space

station crew members, although observed cortisol levels were lower at the mid and late-flight time points. The data confirm that astronauts undertaking long-duration spaceflight experience

both increased latent viral reactivation and changes in diurnal trajectory of salivary cortisol concentrations. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS REACTIVATION OF LATENT HUMAN

INTRACELLULAR INFECTIONS DURING A MONTHS-LONG EXPEDITION AT THE ANTARCTIC VOSTOK STATION Article Open access 22 March 2025 TIME-LAG OF URINARY AND SALIVARY CORTISOL RESPONSE AFTER A

PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESSOR IN BONOBOS (_PAN PANISCUS_) Article Open access 12 April 2021 SEROPREVALENCE AND MOLECULAR DIVERSITY OF HUMAN HERPESVIRUS 8 AMONG PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV IN

BRAZZAVILLE, CONGO Article Open access 31 August 2021 INTRODUCTION Increased reactivation of some naturally occurring latent herpes viruses including Epstein–Barr virus (EBV),

varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) was previously demonstrated in astronauts during short-duration (10–16 days) space shuttle flights.1 However, following reactivation,

viruses were shed in body fluids and the astronauts were typically asymptomatic.2 Stress responses associated with spaceflight include activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and

the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axes 3 and may result in the reactivation of latent herpes viruses subjecting astronauts to risk of shedding live, infectious viruses during spaceflight.4,

5 Cortisol and dehydoepiandosterone (DHEA) may affect regulation of cellular immunity resulting in reactivation of latent viruses.4 Responses to reactivation of herpes viruses can be

asymptomatic, debilitating, or even life-threatening. Isolation of crewmembers before flight has no mitigating effect on latent virus reactivation. Even a complete quarantine does not

prevent viral reactivation during spaceflight.5 The goal of this study was to determine whether long-duration (up to180 days) spaceflight aboard the international space station (ISS) would

allow astronauts to acclimate to spaceflight and mitigate the impact of spaceflight associated stressors on crewmembers.6 In the present study, viral reactivation and shedding of EBV, VZV,

CMV, HSV1, and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) were measured in 23 US astronauts before, during, and immediately following long duration spaceflight. Recently, immune changes were shown to

persist during and after long-duration ISS missions in the same participants as studied in the present virus study.7 In an environment of immune dysfunction, our hypothesis is that viral

reactivation and shedding of these herpes viruses will also increase in astronauts during long-duration space flight as observed in ground-based space analogs.8 RESULTS VIRAL REACTIVATION

Twenty-two of 23 astronauts shed one or more target viruses (Table 1). Fifteen astronauts shed VZV, 22 shed EBV, and 14 shed CMV at one or more time points before, during, or after

spaceflight (Table 1). One astronaut did not shed any virus during any defined collection time. By contrast, none of the 20 control subjects shed VZV or CMV and only 2 of them shed EBV

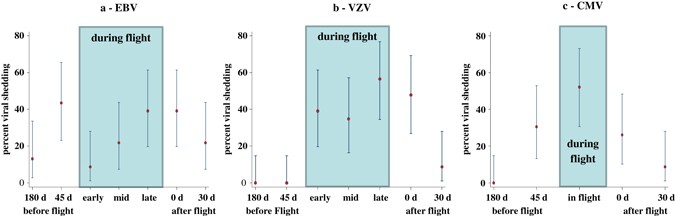

(Table 1). No astronauts or control subjects shed HSV1, HSV2, or HHV6 at any time throughout the study. Percent shedding among crewmembers with 95% binomial confidence intervals are shown

for EBV, VZV, and CMV in Fig. 1. For these three viruses, there was considerable variation of the shedding percentages over the collection time points (Fig. 1) suggesting a possible overall

mission effect on the reactivation of these viruses. More formally, when comparing copy numbers between time points, the Friedman test did not show a significant difference between time

points for EBV (_P_ = 0.064). Indeed, EBV was shed at all seven sample collection time points (Two before, three during, and two after flight). For VZV, no shedding occurred at both 180 days

and 45 days before flight but shedding was found in early, mid, and late time points during flight as well as at landing and 30 days after landing (Table 1). The Friedman test comparing

copy number distributions was significant for VZV (_P_ < 0.0001). After adjustment for multiple comparisons, we found significantly more VZV reactivation in the late-flight time period

than either pre-flight (_P_ = 0.011) or 30d-post-flight (_P_ = 0.035). There was no CMV shedding at 180 days before flight but there was CMV shedding 45 days before, during, and after

flight. The Friedman test comparing copy numbers for CMV was also significant (_P_ < 0.0001). In particular, also after adjustment for multiple comparisons, we found that this was due to

increased CMV shedding during flight which was significantly greater than 180 days before flight (_P_ = 0.013) and also greater than 30 days after flight (_P_ = 0.041). Even when the time

points with no shedding were excluded from the analysis, there were still significant differences between the remaining time points; _P_ = 0.0027 (VZV) and _P_ = 0.0008 (CMV) (Fig. 1). Viral

copy numbers for positive tests had skewed distributions, so we show results in terms of medians rather than means. For the same viruses as above, Figure 2 shows median number of copies for

EBV, VZV, and CMV along with 95% confidence limits obtained from mixed-model regression analysis. The overall mission effect on copy numbers was evident for EBV _(P_ < 0.001), VZV (_P_ =

0.057), and CMV (_P_ = 0.001). For EBV, post-hoc comparisons with Sidak-adjusted _P_-values reflected higher median viral copies during the last two flight periods (Mid, Late) relative to

pre-flight (_P_ < .001, both comparisons) and relative to 30 days post-flight (_P_ < 0.001, both comparisons). Median copies for early recovery (at landing) were not significantly

higher than preflight (unadjusted _P_ = 0.08) (Fig. 2). For CMV, the median copy number was significantly higher during flight than before flight (_P_ < 0.001), but not for landing day

(unadjusted _P_ = 0.56) or 30 days after landing (unadjusted _P_ = 0.55). No post-hoc comparisons were made for median copies of VZV because the overall mission effect was not significant.

EBV DNA LEVELS IN PERIPHERAL BLOOD MONONUCLEAR CELLS (PBMCS) EBV DNA levels varied considerably: from below or at the detectable limit of 2 copies (55 cases) to a maximum of 71,500 copies,

with 25 instances of at least 1000 copies being detected. Because of this high degree of variation, we did not find a significant difference between median copy levels over the time points

as a whole (_P_ = 0.21, median regression analysis), although it did appear that median copies were somewhat elevated at the later time points (Fig. 3). PLASMA CORTISOL Median plasma

cortisol levels ranged from 15.2 μg/dL (late flight) to 24.8 μg/dL (late recovery). The overall test for differences in medians between the seven time points was not significant

(bootstrapped median regression: _P_ = 0.086). Estimates of medians and 95% confidence limits for each time point are shown in Fig. 4. SALIVARY CORTISOL AND DHEA With natural log cortisol

concentration as outcome, there was some evidence that daily mean trajectories for each of the three during-flight periods differed from the trajectories before flight (unadjusted _P_ =

0.069, 0.022, 0.086 by mixed-model regression on log cortisol concentration values for early-flight vs. before-flight, mid-flight vs. before-flight, and late-flight vs. before-flight,

respectively). However, the flight periods did not differ significantly between themselves (_P_ = 0.132). After combining data across the three flight periods and comparing the mean daily

trajectory during flight with pre-flight, we found evidence for an effect of flight (_P_ = 0.010, see Appendix). With one outlier subject removed (see details in the Appendix), there was

even stronger evidence of a flight effect (_P_ = 0.0015). Figure 5a shows the predicted mean daily trajectory of log cortisol concentration before flight and during flight with 95%

confidence limits. The difference was greatest around the middle of the waking period (about 10 h). A plot of this difference vs. hours since awakening with 95% confidence limits is shown in

Fig. 5b. There was no evidence that the mean cortisol trajectory during the first period after flight was different from pre-flight (_P_ = 0.42). There was some evidence of a difference

between the second recovery period and before flight (unadjusted _P_ = 0.048) (see Discussion). Estimated diurnal declines of DHEA did not change as a function of study phase. Figure 6a

shows these trends (on a log scale) for the before and during flight periods and Fig. 6b shows the estimated difference in these trends between the “during flight” and “before flight”

periods. ANTI-VIRAL ANTIBODIES After adjusting for differences between subjects, titer levels of anti-EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) antibodies appeared increased relative to the first

pre-flight period. However, because of high variability we found no significant difference between the periods (_P_ = 0.53, repeated measures ordered logit analysis). Similarly we could not

detect any effect of flight on anti-CMV VCA antibodies (_P_ = 0.79). DISCUSSION This is the first study of reactivation of multiple latent herpes viruses in astronauts during long-duration

spaceflight (60–180 days). We have previously shown a direct correlation of immune changes and viral reactivation in a study of 17 astronauts during short-duration (10–16 days) spaceflight.1

In those subjects, substantial changes in cell-mediated immunity were found in most astronauts that reactivated one or more of the target herpes viruses.1, 7 Glaser9 previously showed

association of EBV reactivation and diminished cell-mediated immunity. Short-duration spaceflight onboard the space shuttle is a unique experience that includes a unique set of stressors

that contribute to the dysregulation of immune and endocrine systems).6, 10 Astronauts on ISS missions experience many similar stressors for a much longer duration. Recent studies confirmed

that astronauts on the ISS continue to experience dysregulation of immune and endocrine systems.6, 10 Increased levels of plasma and urinary stress hormones (cortisol, and catecholamines)

commonly accompany spaceflight.11, 12 Virus reactivation was shown to be associated with the unique combination of stressors associated with spaceflight which include psychosocial stressors

of isolation, confinement, anxiety, sleep deprivation, as well as physical exertion, noise, increased radiation, and microgravity.1, 13 These stressors may be constant or intermittent. It

has been previously suggested that during 4–6 months of spaceflight, astronauts onboard the ISS would acclimate to the unique environment resulting in the recovery of the immune system to

normal levels. Therefore, the immune and viral reactivation observations during 10–16 days space shuttle missions may not occur in crewmembers of 4–6 month missions.6 Normal immune activity

is likely to prevent or mitigate the shedding of the herpes viruses (with exception of EBV) as observed in control subjects. Data in the present study demonstrate that shedding of EBV, CMV,

and VZV did not abate during the longer missions onboard the ISS. Rather, virus shedding actually increased in frequency and amplitude (viral copy numbers) of all three viruses tested. As

shown in Table 2, VZV shedding increased from 41% in short duration space shuttle to 65% in long duration ISS, EBV increased from 82 to 96%, and CMV increased from 47 to 61% of the

crewmembers. Also, shedding for all three viruses persisted throughout the long duration (Early, Mid, and Late) missions. In addition, VZV and CMV shed up to 30 days after longer-duration

spaceflight on the ISS unlike for the short-duration spaceflight on the space shuttle where VZV was shed only up to 5 days and CMV shed up to 3 days after flight.5, 14 In a recent study, it

was reported that immune changes observed in short duration spaceflight actually increased in astronauts after 6 months of ISS flight.7 EBV infects approximately 90% of human adults, and

100% of all astronauts (_n_ = 86) studied to date were seropositive for EBV.1, 5, 14 In this study, all but one of the 23 astronauts studied shed EBV at some time point. VZV is an important

health risk to crewmembers (some have experienced shingles before or during the course of spaceflight), and CMV can be immuno-suppressive.15 CMV may play a role in immune dysfunction

observed in crewmembers. Viral reactivation has been reported in ground-based models of spaceflight although to a lesser extent than spaceflight.16, 17 Previously, we have shown that the VZV

shed in saliva by crewmembers contains live, infectious virus capable of infecting other crew members.18, 19 However, if crewmembers have had exposure to VZV, it is not likely to re-infect

but they may spread live infectious virus to immunocompromised or sero-negative individuals with whom they come in contact during or after the flight. Reactivation of VZV can result in

shingles or other serious health issues that can compromise mission objectives. EBV shedding was found in 3% of control subjects while VZV and CMV were found in less than 1%.1, 5, 14 Even

though the exact mechanism of virus shedding in saliva of astronauts during flight is not fully understood, increased stress and reduced immunity are important contributory factors.9, 20 VZV

is a neurotropic virus that does not appear in saliva of normal healthy subjects.21 However, stressful conditions such as spaceflight can reactivate this virus to replicate in the dorsal

root ganglia, and shedding occurs in saliva.22 The apparent higher salivary cortisol profile predicted in diurnal cortisol (Fig. 5) is similar to dysregulation associated with psychosocial

challenges such as chronic caregiving stress,23, 24 early trauma,25 and breast cancer.26 Herein with longitudinal sampling during the course of extended space flight, there were indications

of disruption in cortisol levels reflected by a higher diurnal level at mid-day. Our previous report for short-term space flight suggested that cortisol levels remained unchanged when

applying a different metric, area under the curve.1 These differences could be due to the impact of longer exposure to microgravity,radiation, work load, and psychological factors operating

in longer missions. Furthermore, in the MARS500 investigation,27 no relevant shedding was observed during or after isolation, again suggesting the impact of spaceflight (in particular,

long-duration spaceflight) as a key contributor to the current findings. The lack of psychological assessments addressing stress levels in crewmembers is a limitation of the present study.

Additonally the inability to precisely time each sample collection within a 24-h cycle, limits our capacity to speculate on sources of midday increases. Improved documentation of daily

activities on when saliva was collected would contribute significantly to interpreting these observations. However the contraints in collection from rigidly scheduled crewmembers precludes

collecting additional information of this nature. Controlling the reactivation of latent herpes viruses is among the numerous functions of T cells. Percentages of virus-specific T cells have

been found to be elevated after short-duration spaceflight.28 An investigation of immunity after short duration space shuttle missions found no significant increases in the absolute levels

of peptide-specific EBV or CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. However, CD8+ T-cell subsets, including cytotoxic, central memory, and senescent; T-cell function; and cytokine production profiles were

altered during short-duration spaceflight.6 The functional capacity of virus-specific T cells during this previous study was in fact decreased.6 CONCLUSIONS Previously, we showed that at

least three latent herpes reactivate and shed in astronauts during short-term spaceflight.1, 5, 14 Changes in immunity were also observed6 and provided a likely mechanistic cause for

reactivation of latent viruses.6, 7 This study was undertaken to determine if the longer duration missions resulted in a reduction in stress effects and restored viral immunity thus

preventing or mitigating the reactivation of these viruses. Unfortunately, in this long duration (6 months) ISS study, immune status did not improve7 and consequently, reactivation of EBV,

VZV, and CMV actually increased in frequency, duration, and amplitude (viral copy numbers) when compared to values found with short-duration spaceflight. The viruses studied reactivated

independently of each other. These findings could impact the design of exploration-class missions during which reactivation of latent viruses could result in an increased risk of

wide-ranging adverse medical events.10 It may be however, that a partial-gravity environment, e.g., on Mars, would be sufficient to prevent serious viral reactivation. Future research needs

to address this question. For now, we conclude that because astronaut’s saliva has significantly increased shedding of VZV DNA during and after spaceflight and this virus has been shown to

be infectious in an earlier study,19 vaccination of crewmembers with VZV vaccine (zostavax) may be recommended as a countermeasure to the astronauts before they go in space. MATERIALS AND

METHODS SUBJECTS Twenty-three ISS astronauts (18 male and 5 female; mean age + SE = 53 + 4.9 years) participated in this observational study. These study participants are the same

individuals that participated in a recent immune study.7 Informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in the study and the study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board at the Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas. The nominal mission duration was approximately 180 days. Two crewmembers participated in shorter missions of approximately 2–3 months. For

those crewmembers; only two samplings occurred during flight, with data aligned with the ‘early’ and ‘mid’ for the 6-month crewmembers. Twenty apparently healthy age—and gender matched

subjects (16 males and 4 females, mean age ± SE of 49.3 ± 4.9 years) participated as ground-based viral reactivation controls. With the exception of the diurnal saliva collections, the

control subjects were sampled and processed at the same time for the same assays as the ISS crewmembers. All astronauts and control subjects were EBV, CMV, VZV, and HSV-1 seropositive as

tested by measuring IgG with an ELISA based commercial assay at baseline (180 days before flight) assessment. A total of 1044 samples from 23 astronauts were collected before, during and

after long-duration spaceflight on the ISS and were analyzed upon return to Earth. Saliva accounted for 644 samples, 207 samples were urine, and 193 were blood samples. Saliva samples were

assayed for EBV, VZV, and HSV-1/2 and HHV6; urine samples were analyzed for CMV. This study was observational and exploratory, making use of all data from participating astronauts, and as

such was not designed to achieve any particular level of power for detecting pre-specified effects, nor could this work be replicated in a laboratory setting. SAMPLE COLLECTION Saliva

samples for viral assessments were collected using Salivette cotton rolls (Sarstedt, Inc., Newton, NC immediately after their sleep cycle, before eating and brushing their teeth. To collect

a sample, the subject placed the cotton roll in their mouth until it became saturated with saliva (2–3 min). The saturated salivette was then placed in a Ziploc® bag containing 1 mL of

stability buffer (0.5% SDS, 10 mM Tris-Cl, and 1 mM EDTA. The samples were stored at ambient temperature for approximately 2 weeks before return to Earth for analysis.1 Four saliva samples

were collected at each of 7 sampling sessions, approximately corresponding to the following time points: Sessions 1–2: 180 and 45 days before flight; Sessions 3–5: during flight at mission

day 14 days (early), between mission days 60–120 days (mid-mission) and about 180 days (late); Sessions 6–7: 3 h after landing and 30 days after landing (Fig. 1). A 10 mL EDTA anti

coagulated peripheral blood sample and a 24-h urine pool were also collected before and after each mission time point. Only one blood sample was taken at each inflight time point, as shown

in Table 3. Samples for control subjects (four saliva samples, a urine sample from a 24-h pool, and a blood sample (10 mL, EDTA) were collected at corresponding time points for a 6—month

simulated spaceflight mission. Control samples were treated the same way as astronauts’ samples and processed in batches after each subject completed the simulated spaceflight schedule.

Urine samples from the participating crewmembers were obtained via a sample sharing agreement with another NASA investigation. Twenty four-hour urine pool samples were collected before and

after flight. Urine voids during flight contained 1 mL of a LiCl solution as a volume marker. The 24-h urine pool was thoroughly mixed, and a syringe aliquot was obtained and then frozen

until return to Earth for analyses about 6–12 months later. After landing, the flight urine samples were analyzed for lithium concentration to determine void volume and subsequently to

prepare 24-h pools, as previously described.29, 30 SAMPLE PROCESSING AND STORAGE Upon return to Earth, flight saliva samples collected via Salivettes were centrifuged to separate fluid from

the cotton, and the supernatant fluid was stored frozen (−70 °C) until processed. Ground-based analysis verified that the stability buffer preserved viral DNA in saliva for subsequent

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for up to 240 days14 Ten-fold concentration of saliva was achieved by centrifugation using a Microsep concentrator 100kD (Pall Filtron Corp.,

Northborough, MA). For CMV, urine (3 mL) was concentrated to ~200 µL using a 100 kD filtration unit as mentioned above. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −70 °C until

processed. All samples collected from each subject were processed together to avoid inter-assay variations between subjects or assay inconsistencies between laboratories. DETECTION OF VIRAL

DNA Viral DNA was extracted by a nonorganic extraction method (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA) QIAamp Viral RNA Kits (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, CA) were used to extract viral genomic DNA from

concentrated saliva and urine, and each assay was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. HSV1, HSV2, EBV, HHV6, and VZV DNA were measured in saliva and CMV DNA in urine by

real-time PCR using an ABI 7900 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) PCR system. The primers and probes used for EBV, VZV, and CMV have been published previously.1 MEASUREMENT OF ANTIBODY

TITER Anti-viral antibody titers were determined by indirect immunofluorescence as previously described.31 Commercially prepared substrate slides and control sera (Bion Enterprises, Park

Ridge, IL) were used for determining IgG antibody titers to EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) and early antigen, EBV-nuclear antigen, VZV, and CMV as described.1 DIURNAL SALIVARY CORTISOL AND

DHEA Diurnal dry saliva samples (5 per sampling day) were collected at awakening and 30 min, 6 h, and 10 h after awakening, as well as on retiring, using a unique filter-paper collection

method. In short, the subject wet the filter paper with saliva, which was then air-dried at room temperature storage until return to Earth. All of a subject’s samples were assayed on the

same plate. Filters were processed for cortisol and DHEA in a similar manner as previously described.32, 33 Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for cortisol and DHEA were

less than 5 and 10%, respectively, using this procedure. MEASUREMENT OF PLASMA CORTISOL Stored plasma samples were thawed, and cortisol was measured by EIA using commercially available kits

(Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH). Samples were batch analyzed to minimize inter-assay variation. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS VIRAL REACTIVATION For each subject, EBV and VZV maximum copy numbers

within the four replicate saliva samples at each of 7 time points were analyzed to (a) compare the effect of mission time points on all copy numbers (including zeroes for cases of no

shedding) and (b) to compare means of log-transformed copy numbers for those samples in which a virus was shed. Single values of CMV copies were similarly analyzed as is. For (a) above we

used Friedman’s rank-based ANOVA34 with follow-up multiple comparisons if the overall test for equal mean ranks was rejected (two-sided _p_ < 0.05). No analysis was made on data from

HSV1, HSV2, and HHV6 since these viruses were not shed at any time point. For (b) we used mixed model linear regression analysis35 with Sidak-adjusted _P_-values for post-hoc comparisons of

each time point to the previous one. ANTIBODY TITERS By nature, antibody titers are discrete, taking only relatively few distinct values. Therefore, we compared the antibody titers between

time points with a repeated-measures version of an ordered logit regression model,36 which is designed to analyze ordered categorical data. EBV-DNA COPIES This data was highly variable, with

a considerable number of observations below detectable limits (2 copies), while others ranged over several orders of magnitude. We analyzed this outcome using median regression37 with

samples below detection limits being treated as having produced 2 copies. PLASMA CORTISOL Median plasma cortisol levels at the seven time points were compared using median regression with

cluster bootstrapped samples at the subject level. The presence of a few outliers, which were verified to be valid, precluded the use of mixed-model regression for this purpose. HORMONE DATA

(SALIVA) The main outcomes here were cortisol concentration (μg/dl) and DHEA concentration (pg/mL) measured at various hours within a day, starting at awakening. The goal of the analysis

was so see if the mean daily trajectories of these outcomes differed by flight period or phase. To do this we constructed random-effects regression models35 (one for each mission time point)

for the mean daily trajectories of each outcome on a log scale using a 3-knot cubic spline, then compared the parameters of the regression model between pre-flight and each of the other

phases. Comparisons were assessed in terms of two-sided _P_-values with Bonferroni adjustment when appropriate. Model assumptions were checked with Q–Q plots of residuals. Cortisol data

collected within 1 h after awakening was not used in any of the analyses because this value represents a different underlying control system38 as well as the difficulty of modeling the high

variability associated with the rise in cortisol concentration at that time. A detailed description of these types of analyses as well as an example of one such analysis is given in

supplementary information files. CODE AVAILABILITY All statistical analyses were performed with user-written sequences of commands in Stata 14 software. Some of these commands may be seen

preceding the analysis results in the supplementary material. REFERENCES * Mehta, S. K. _et al._ Multiple latent viruses reactivate in astronauts during space shuttle missions. _Brain Behav.

Immun._ 41, 210–217 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mehta, S. K. _et al._ Stress-induced subclinical reactivation of varicella zoster virus in astronauts. _J. Med. Virol._

72, 174–179 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Goldstein, D. S. Adrenal responses to stress. _Cell. Mol. Neurobiology_ 30, 1433–1440 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Padgett,

D. A., Loria, R. M. & Sheridan, J. F. Steroid hormone regulation of anti-viral immunity. _Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci._ 917, 935–943 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Pierson, D. L., Mehta, S.

K., Stowe, R. P. in _Psychoneuroimmunology_ 4th edn, (ed Ader, R.) Ch. Reactivation of latent herpes viruses in astronauts (Elsevier Academic Press, 2007). * Crucian, B. R. _et al._ Immune

system dysregulation occurs during short duration spaceflight on board the space shuttle. _J. Clin. Immunol._ 33, 456 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Crucian, B. _et al._

Alterations in adaptive immunity persist during long-duration spaceflight. _npj Microgravity_ 10, 1038 (2015). Google Scholar * Mehta, S. K., Pierson, D. L., Cooley, H., Dubow, R. &

Lugg, D. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation associated with diminished cell-mediated immunity in antarctic expeditioners. _J. Med. Virol._ 61, 235–240 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Glaser, R. _et al._ Stress and the memory T-cell response to the Epstein-Barr virus in healthy medical students. _Health Psychol._ 12, 435–442 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Crucian, B. & Sams, C. Immune system dysregulation during spaceflight: clinical risk for exploration-class missions. _J. Leukoc. Biol._ 86, 1017–1018 (2009). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Stowe, R. P., Pierson, D. L. & Barrett, A. D. T. Elevated stress hormone levels relate to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in astronauts. _Psychosom. Med._ 63,

891–895 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stowe, R. P., Pierson, D. L., Feeback, D. L. & Barrett, A. D. Stress-induced reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus in astronauts.

_Neuroimmunomodulation_ 8, 51–58 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nicogossian, A. E. _et al_. (eds) _Space Physiology and Medicine_. 3 edn, (Lea and Febiger, 1994). * Pierson,

D. L., Stowe, R. P., Phillips, T. M., Lugg, D. J. & Mehta, S. K. Epstein-Barr virus shedding by astronauts during space flight. _Brain Behav. Immun._ 19, 235–242 (2005). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Nokta, M. A., Hassan, M. I., Loesch, K. & Pollard, R. B. Human cytomegalovirus-induced immunosuppression. Relationship to tumor necrosis factor-dependent

release of arachidonic acid and prostaglandin E2 in human monocytes. _J. Clin. Invest._ 97, 2635–2641 (1996). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mehta, S. K., Crucian,

B., Pierson, D. L., Sams, C. & Stowe, R. P. Monitoring immune system function and reactivation of latent viruses in the Artificial Gravity Pilot Study. _J. Gravit. Physiol._ 14, 21–25

(2007). Google Scholar * Mehta, S. K. & Pierson, D. L. Reactivation of latent herpes viruses in cosmonauts during a Soyuz taxi mission Bremen. _Microgravity Sci Technology._ XIX,

215–218 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Cohrs, R. J. _et al._ (eds) _Asymptomatic Alphaherpesvirus Reactivation. Herpesvirdae Viral Structure, Life Cycle and Infection_ (Nova Medical

Books, 2009). * Cohrs, R. J., Mehta, S. K., Schmid, D. S., Gilden, D. H. & Pierson, D. L. Asymptomatic reactivation and shed of infectious varicella zoster virus in astronauts. _J. Med.

Virol._ 80, 1116–1122 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Glaser, R. _et al._ Stress-related impairments in cellular immunity. _Psychiatry Res._ 16, 233–239

(1985). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Birlea, M. _et al._ Search for varicella zoster virus DNA in saliva of healthy individuals aged 20-59 years. _J. Med. Virol._ 86, 360–362

(2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gilden, D., Mahalingam, R., Nagel, M. A., Pugazhenthi, S. & Cohrs, R. J. Review: the neurobiology of varicella zoster virus infection.

_Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol_ 37, 441–4463 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sannes, T. S., Mikulich-Gilbertson, S. K., Natvig, C. L. & Laudenslager, M. L.

Intraindividual cortisol variability and psychological functioning in caregivers of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. _Psychosom. Med._ 78, 242–247 (2016). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Savla, J. _et al._ Cortisol, alpha amylase, and daily stressors in spouses of persons with mild cognitive impairment. _Psychol Aging_ 28, 666–679 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Miller, G. E., Chen, E. & Zhou, E. S. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans.

_Psychol. Bull._ 133, 25–45 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sephton, S. E., Sapolsky, R. M., Kraemer, H. C. & Spiegel, D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast

cancer survival. _J. Nat. Cancer Inst_. 92, 994–1000 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yi, B. _et al._ 520-d isolation and confinement simulating a flight to Mars reveals

heightened immune responses and alterations of leukocyte phenotype. _Brain Behav. Immun._ 40, 203–210 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stowe, R. P. Impaired effector function

in virus-specific T cells in astronauts NASA Human Research Program Investigators Meeting, Houston, Texas 2003. * Smith, S. M. _et al._ Calcium metabolism before, during, and after a 3-mo

spaceflight: kinetic and biochemical changes. _Am. J. Physiol._ 277, 1–10 (1999). Article Google Scholar * Smith, S. M. _et al._ Bone markers, calcium metabolism, and calcium kinetics

during extended-duration space flight on the mir space station. _J. Bone Miner. Res._ 20, 208–218 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lennette, E. T. in _Manual of Clinical

Microbiology_ 6th edn, (ed Murray, P. R.) Ch. Epstein-Barr virus (ASM Press, 1995). * Laudenslager, M. L. “Anatomy of an Illness”: control from a caregiver’s perspective. _Brain Behav.

Immun._ 36, 1–8 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Laudenslager, M. L., Calderone, J., Philips, S., Natvig, C. & Carlson, N. E. Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and DHEA

using a novel collection device: electronic monitoring confirms accurate recording of collection time using this device. _Psychoneuroendocrinology_ 38, 1596–1606 (2013). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gibbons, J. D. & Chakraborti, S. (eds) _Nonparametric Statistical Inference_ (Marcel Dekker, 2003). * Diggle, P. _et al_. (eds) _Analysis of

Longitudinal Data_ (Clarendon Press, 1995). * Skrondal, A. _et al_. (eds) _Generalized Latent Variable Modeling: Multilevel, Longitudinal, and Structural Equation Models_ (Chapma, 2004). *

Greene, W. H. _et al_. (eds) _Econometric Analysis_ (Prentice Hall, 2000). * Clow, A., Hucklebridge, F., Stalder, T., Evans, P. & Thorn, L. The cortisol awakening response: more than a

measure of HPA axis function. _Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev._ 35, 97–103 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully acknowledge the

conscientious participation of the astronauts in the study. This work was supported by NASA grants 111-30-10-03 and 111-30-10-06 to DLP. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Jestech, Johnson Space Center, NASA, Houston, TX, 77058, USA Satish K. Mehta * University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus, 12700 E. 19th Ave, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA Mark L.

Laudenslager * Microgen Laboratories, 903 Texas Ave, La Marque, TX, 77568, USA Raymond P. Stowe * NASA Johnson Space Center, Mail code SK, 2101 NASA Parkway, Houston, TX, 77058, USA Brian E.

Crucian, Alan H. Feiveson, Clarence F. Sams & Duane L. Pierson Authors * Satish K. Mehta View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mark L.

Laudenslager View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Raymond P. Stowe View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Brian E. Crucian View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alan H. Feiveson View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Clarence F. Sams View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Duane L. Pierson View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Satish K. Mehta. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing

interest. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL APPENDIX SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not

included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Mehta, S.K., Laudenslager, M.L., Stowe, R.P. _et al._ Latent virus reactivation in

astronauts on the international space station. _npj Microgravity_ 3, 11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-017-0015-y Download citation * Received: 21 September 2016 * Revised: 21

December 2016 * Accepted: 07 January 2017 * Published: 12 April 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-017-0015-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able

to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative