A unified model of human hemoglobin switching through single-cell genome editing

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Key mechanisms of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) regulation and switching have been elucidated through studies of human genetic variation, including mutations in the _HBG1/2_ promoters,

deletions in the β-globin locus, and variation impacting BCL11A. While this has led to substantial insights, there has not been a unified understanding of how these distinct

genetically-nominated elements, as well as other key transcription factors such as ZBTB7A, collectively interact to regulate HbF. A key limitation has been the inability to model specific

genetic changes in primary isogenic human hematopoietic cells to uncover how each of these act individually and in aggregate. Here, we describe a single-cell genome editing functional assay

that enables specific mutations to be recapitulated individually and in combination, providing insights into how multiple mutation-harboring functional elements collectively contribute to

HbF expression. In conjunction with quantitative modeling and chromatin capture analyses, we illustrate how these genetic findings enable a comprehensive understanding of how distinct

regulatory mechanisms can synergistically modulate HbF expression. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE-LEVEL MAPPING OF DNA REGULATORY ELEMENTS THAT CONTROL FETAL

HEMOGLOBIN EXPRESSION Article 06 May 2021 ACTIVATION OF Γ-GLOBIN GENE EXPRESSION BY GATA1 AND NF-Y IN HEREDITARY PERSISTENCE OF FETAL HEMOGLOBIN Article 02 August 2021 POTENT AND UNIFORM

FETAL HEMOGLOBIN INDUCTION VIA BASE EDITING Article 03 July 2023 INTRODUCTION The regulation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) has been of substantial interest, both for its value to enable improved

therapies to elevate HbF as a treatment in sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, as well as for its broader implications as a paradigm for understanding the developmental control of gene

expression1,2,3. A number of studies have provided insights into HbF regulation through the identification and analysis of naturally occurring mutations impacting this process. Such variants

have been extensively characterized at two distinct loci: (1) in the gene encoding the BCL11A transcription factor and (2) within the β-globin gene locus that harbors the HbF genes, _HBG1_

and _HBG2_. Both common and rare variants in the _BCL11A_ gene alter HbF expression in erythroid cells, with rare loss-of-function variants resulting in substantially increased

HbF4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Other studies focused on the β-globin locus have identified a number of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small deletions in the _HBG1_ and _HBG2_ proximal promoters

that allow upregulation of HbF levels to varying extents (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 1)11,12. Recent studies have begun to elucidate how specific variants in these proximal promoters act

by either preventing or facilitating the interactions of _trans_-acting regulatory factors, most notably the key HbF silencing factors BCL11A and ZBTB7A, with specific sequences13,14,15,16.

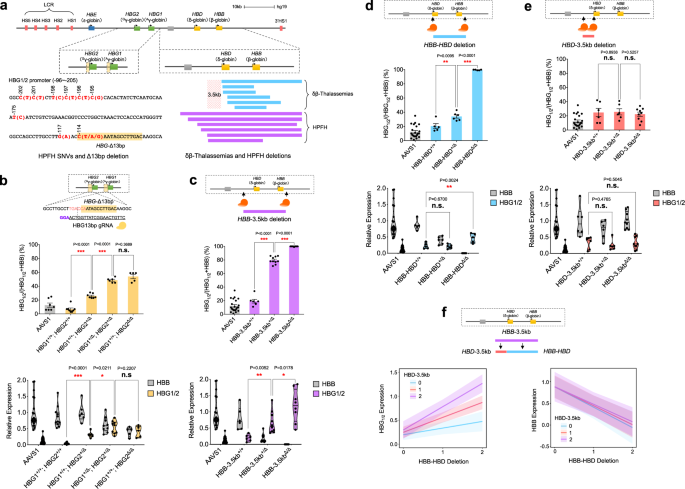

In addition to variants affecting the _HBG1_/_2_ proximal promoters, large deletions that span the entirety of the adult β-globin _HBB_ and _HBD_ genes also increase HbF expression to

varying extents. Such deletions can be broadly classified into two categories: those that have higher _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA and therefore HbF production, termed hereditary persistence of fetal

hemoglobin (HPFH) deletions, and those that are characterized by lower HbF production with resultant globin chain imbalance, termed δβ-thalassemia (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). We and

others have suggested that a 3.5 kb region upstream of the _HBD_ gene may underlie the difference between these two groups of deletions, although this remains to be functionally

tested17,18,19. Despite the substantial knowledge that has arisen through these studies, which have primarily focused on one type of genetic variant or another in isolation, a holistic view

of HbF regulation has yet to emerge. Recent work has cataloged and defined biochemical interactions and epigenetic marks that occur across the β-globin locus, including several binding sites

for BCL11A and binding sites within the _HBG1_/_2_ promoters for ZBTB7A (Supplementary Fig. 1b). However, a unified model integrating how these various regions of the β-globin locus

interact has not yet been produced. One impediment to achieving this goal has been the inability to study humans with combinations of these rare variants that have a major impact on HbF

levels. Furthermore, a number of experimental limitations have constrained potential insights in cellular models. While genome editing in transformed erythroid cell lines has enabled clonal

analysis, some observations made in primary human hematopoietic cells cannot be faithfully recapitulated in this context18. Moreover, despite the fact that genome editing in primary

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) has progressed significantly20, such perturbations create a heterogeneous array of edits that can typically only be analyzed in bulk. Here we

sought to address these limitations in order to capture a more unified view of HbF regulation. We began by developing a system using genome editing capable of recapitulating specific

mutations either individually or in combination. By integrating this with functional analysis of distinct genome edits in the progeny of single human HSPCs, we are able to assess the

specific outcome of these edits upon HbF regulation at single-variant resolution. Through quantitative modeling of this data, we illuminate functional genetic interactions between specific

perturbations involving these regulatory elements. We bolster these findings through the biochemical analysis of locus-specific long-range chromatin interactions using the CRISPR affinity

purification in situ of regulatory elements (CAPTURE) approach and with chromosome conformation capture (3C) in the presence or absence of BCL11A21,22. These holistic analyses provide

previously unappreciated insights into the overarching mechanisms necessary for HbF expression and switching. More broadly, we also illuminate the value of performing single-cell individual

and combinatorial functional perturbations that are inspired by human genetic variation. RESULTS A SINGLE-CELL GENOME-EDITING FUNCTIONAL ASSAY FOR GLOBIN GENE REGULATION We initially aimed

to create a system to address two major limitations that exist in this field. First, while transformed clonal erythroid cell lines enable analysis of specific regulatory elements,

perturbations in these cell models may not always faithfully recapitulate in vivo observations18. Second, combinations of these rare genetic perturbations are almost never observed in

humans, thus limiting inferences that can be made using in vivo data11. To overcome these limitations, we sought to create specific genetic perturbations guided by natural genetic variation

through genome editing in an isogenic setting using human HSPCs from healthy donors. These could then be plated at low density in semi-solid medium to form erythroid colonies (burst-forming

unit erythroid (BFU-E) colonies) from which cells derived from a single progenitor could be isolated for paired RNA and DNA analyses23. We have previously shown that single-cell analysis of

individual cells derived from BFU-E colonies demonstrate close clonal relationships, as assessed by sharing of mitochondrial DNA mutations, and each of the single erythroblasts from any

BFU-E cluster closely together using gene expression profiling, irrespective of donor24. Therefore, by isolating the hundreds to thousands of differentiated erythroblasts in each BFU-E

colony derived from a single distinct edited HSPC, we could obtain information on the specific genotype present in that colony and simultaneously interrogate the impact on globin gene

regulation in the same colony (Supplementary Fig. 2). We hypothesized that this approach would enable us to study the impact of each individual genetic mutation and combinations of these

perturbations to gain a more complete understanding of HbF regulation. Furthermore, we expected that existing genome-editing tools would enable us to recreate each category of the

well-characterized rare perturbations that significantly alter HbF, including variants in the proximal promoters of the _HBG1_/_2_ genes, deletions involving _HBD_ and _HBB_, and

perturbation of the key _trans_-acting regulatory factors, BCL11A and ZBTB7A (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1b). MODULATION OF HBF REGULATION BY RECAPITULATING SPECIFIC _CIS_-REGULATORY

ELEMENT PERTURBATIONS IN THE PROGENY OF SINGLE CELLS Given the recent identification of key sequence elements that are bound by BCL11A in the _HBG1_ and _HBG2_ promoters15,16,25,26, we first

sought to test this functional assay by recapitulating the 13 bp deletion of these elements that has been observed in vivo27. In bulk, we observed efficient editing and a high frequency of

the 13 bp deletion through sequencing analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). There was robust induction of _HBG1_/_2_ without notable perturbation of erythroid differentiation or maturation

(Supplementary Fig. 4a, b, d). By screening hundreds of colonies, we could obtain numerous independent clones targeted by either the _HBG1_/_2_ promoter guide or with a control

_AAVS1_-targeting guide, which is a genomic region that has no impact on hematopoiesis upon editing28. We initially noted that in _AAVS1_-edited colonies, there was minimal donor-to-donor

variability observed in globin mRNA levels enabling pooling of data across multiple independent donors (Supplementary Fig. 5). By either separating the colonies that harbored disruptive

deletions in either one or both _HBG1_ or _HBG2_ promoters, as well as through aggregate analysis across these homologous genes, we found that each deletion derepressed _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA

expression in an additive manner, without signs of resultant globin chain imbalance (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 6a and 12). Given similar impacts seen with editing at either the _HBG1_

or _HBG2_ promoters, we performed aggregate analysis with these edits together (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and treat these similarly in subsequent modeling. Importantly, we ensured that we did

not analyze deletions or inversions created across the _HBG1_/_2_ region through targeted sequencing approaches. Our findings provide functional validation for the recently emerging models

that BCL11A acts through a sequence element that overlaps the 13 bp deletion to silence the _HBG1_/_2_ genes, while competing with activating factors such as NF-Y, and that each element in

the proximal promoters of these homologous genes appears to act in a semi-autonomous manner15,16,25. We next sought to use the single-cell functional assay to dissect how larger HPFH or

δβ-thalassemia deletions may impact HbF silencing. We initially targeted the region from 3.5 kb upstream of _HBD_ that is commonly removed in many HPFH deletions and concomitantly removed

the region spanning the adult _HBD_ and _HBB_ genes, which is deleted in nearly all HPFH and δβ-thalassemia deletions (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 3a, d, e and 4a, b, e). This resulted

in robust _HBG1_/_2_ expression in both heterozygous and homozygous states without any signs of globin chain imbalance. We additionally examined clones with an inversion of this element,

which displayed globin chain imbalance in contrast to the deletion, despite some elevation of _HBG1_/_2_ expression (Supplementary Fig. 6b). To gain further insights into the elements that

comprise this larger region and how they may function independently, we separately removed the region spanning the adult _HBD_ and _HBB_ genes, which as expected led to a phenotype

characterized by imbalance of the beta-like to alpha-like mRNAs with minimal HbF induction in the heterozygous state (Fig. 1d), or the _HBD_ upstream 3.5 kb region—which is by itself never

removed in any in vivo deletions causing HPFH—that resulted in little HbF induction (Fig. 1e). This data suggested that there is an interaction between these two deleted regions such that

the increase in HbF when both regions are deleted is much greater than would be expected by either deletion alone. These findings provide support for the promoter competition model that has

been proposed to underlie hemoglobin switching, whereby interaction between the locus control region (LCR) enhancer with the adult globin promoters competes with LCR interactions with the

_HBG1_/_2_ promoters3. To quantitatively test this, we fit a linear mixed model (LMM) for _HBG1_/_2_ and _HBB_ mRNA expression to a dosage (0, 1, 2) for each partial deletion, wherein the

larger deletion would consist of both. We also treated the interaction term between the deletions as a fixed effect in the LMM. Moreover, we allowed for random intercepts to account for

donor and guide RNA (gRNA)-based variation when applicable. Importantly, when looking at the model fit to _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA expression, we observe significant reinforcement interactions

(synergy) between these regions in the model (_β_ = 0.17; _P_ value < 0.0001), which can be noted visually by the non-parallel lines of the interaction plot with increasing slopes as

dosages of each deletion increase (Fig. 1f). Conversely, when modeling _HBB_ expression, we see that only the _HBD_-_HBB_ deletion impacts _HBB_ mRNA expression and there is no effect on

this by the _HBD_-3.5 kb region (_β_ = 0.03; _P_ value = 0.55) (Fig. 1f). Collectively, this analysis revealed key _cis_-regulatory elements in both the _HBG1_/_2_ proximal promoters and in

long-range distal elements near the adult globin genes that are critical for HbF silencing. However, we wanted to gain further insights into how these elements could interact with the key

and genetically nominated _trans_-acting regulators of HbF, BCL11A, and ZBTB7A. INSIGHTS FROM PERTURBATION OF BCL11A AND ZBTB7A IN SINGLE PROGENITOR-DERIVED ERYTHROID CELLS We therefore next

sought to characterize the impact of perturbing BCL11A alone in our single cell functional assay. Rare haploinsufficient mutations in BCL11A have been shown to enable significant

persistence of HbF8,9,10. To mimic the impact of these rare variants, we screened several gRNAs and identified two that showed efficient cutting as assessed by indel frequency (62 and 81%

editing efficiency for guides targeting exon 2 and 4, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In bulk, we found no significant perturbation of erythroid maturation and differentiation, while

observing robust HbF induction with both of the guides (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Interestingly, perturbation of exon 4 appeared to result in much higher HbF induction than would be expected

for the degree of editing achieved compared to exon 2 (Supplementary Fig. 7b–d). This prompted us to examine the observed protein expression levels. While targeting of exon 2 resulted in a

reduction of overall BCL11A levels, targeting of exon 4 resulted in an increase in the levels of a truncated protein form of BCL11A, as would be predicted from the commonly observed indels

with this gRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). These results suggest that targeting of exon 4 creates frameshift mutations that bypass nonsense mediated decay pathways, given its location near

the C-terminal end of the protein, and thereby result in the production of dominantly interfering forms of BCL11A that may inhibit activity of a portion of the remaining wild-type (WT)

allele of _BCL11A_. To directly demonstrate dominant negative activity, we expressed the cDNAs encoded by these frameshift mutations and observed increased _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA production in

adult erythroid cells, which is distinct from the _HBG1_/_2_ repression observed with overexpression of the WT cDNA (Supplementary Fig. 8). This finding suggests a possible role for BCL11A

homodimerization in HbF regulation29,30. Alternatively, this dominantly interfering form may sequester co-repressors, given that DNA binding by BCL11A requires zinc fingers 4-6, which would

be removed by these deletions15,31. We transitioned to single cell functional analyses of these edits to assess the consequences across a range of perturbations impacting BCL11A. We observed

robust induction of HbF in cells with heterozygous edits in single HSPCs that underwent erythroid differentiation. We observed an increase in these levels from a baseline of ~20% to ~60%

_HBG1_/_2_ with heterozygous edits, and observed ~94% with homozygous edits at this exon (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Interestingly, with perturbation of exon 4, we observed ~80% _HBG1_/_2_ with

heterozygous edits and ~96% with homozygous edits in single progenitors (Supplementary Fig. 9b). These observations bolstered the data obtained in bulk and enabled us to illuminate the

critical role of BCL11A in HbF silencing in primary cells at single-cell resolution, while also establishing an allelic series for BCL11A perturbations. The exon 4 edits enabled us to alter

activity to a level lower than haploinsufficiency, given dominant negative activity, which together with exon 2 edits provided an allelic series in _BCL11A_ to use in interrogating

functional interactions. We do note that all loss-of-function variants that have been identified in patients with _BCL11A_ haploinsufficiency to date occur in more N-terminal regions of the

protein in comparison to the BCL11A exon 4 guide we selected10, consistent with the resultant dominant interference by indels in this region. While mutations in ZBTB7A have not been found in

individuals with persistence of HbF, this _trans_-acting factor has been genetically-nominated through analysis of _cis_-regulatory elements to which it binds that are disrupted by

mutations associated with elevated HbF levels, including the −195C > G mutation25. As a result, we also disrupted _ZBTB7A_ with gRNAs and examined the consequences of this perturbation in

our single cell functional assay (Supplementary Fig. 10). Consistent with the restricted terminal erythroid defects observed with ZBTB7A perturbation14,32, we found ostensibly normal

erythroid maturation in the targeted cells (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). With this perturbation, we noted an elevation of _HBG1/2_ as a percentage of total β-like globin mRNAs. Interestingly,

there was significant derepression of _HBG1_/_2_, beyond what is observed from reciprocal _HBB_ silencing (Supplementary Fig. 11). This observation suggests that ZBTB7A has a distinct role

in silencing _HBG1_/_2_ and maintaining appropriate expression levels. The significant and out of proportion enhancement of _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA expression compared to the decrease in _HBB_ mRNA

upon ZBTB7A perturbation suggests a key role for ZBTB7A in autonomous silencing of the _HBG1_/_2_ genes. FUNCTIONAL GENETIC INTERACTIONS BETWEEN BCL11A, ZBTB7A, AND Β-GLOBIN LOCUS

_CIS_-REGULATORY ELEMENTS Given the findings from our single cell functional analysis of individual perturbations, we next sought to combine these perturbations to assess for functional

genetic interactions between these distinct regulatory factors. We initially began by combining the perturbation of the _HBG1_/_2_ promoter 13 bp element (herein, Δ13 bp) with targeting of

BCL11A, which has been shown to bind to this region15,25. Interestingly, combined perturbation of Δ13 bp and BCL11A showed non-additive effects across a range of distinct genotypes,

suggestive of a functional interaction (Fig. 2a, c and Supplementary Fig. 12). We applied a LMM to directly quantify this interaction by modeling the impact of individual or combined

perturbations upon _HBG1_/_2_ and _HBB_ mRNA expression. We treated the various _BCL11A_ perturbations as an allelic series based upon their effects with heterozygous exon 2 edits given a

value of 1, heterozygous exon 4 edits given a value of 2 (given greater than haploinsufficient perturbation), and homozygous edits of BCL11A given a value of 3 (“Methods”). As our previous

results had suggested a purely additive effect for _HBG1_/_2_ edits, these were given values of 0-4 to represent the number of _HBG1_/_2_ proximal promoter edits observed in any single cell.

Both allelic series were treated as fixed effects and fit to values of _HBG1_/_2_ and _HBB_ mRNA expression. Random intercepts were allowed, as previously described, to account for donor

and other experimental sources of variation when applicable. The combined effects of BCL11A and Δ13 bp perturbations showed a clear and significant antagonistic interaction with this LMM (β

= −0.12, _p_-value < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c). This finding shows that the _HBG1_/_2_ promoters and BCL11A act via an overlapping and interacting pathway, thus causing non-additive effects upon

perturbation, as seen by the decreasing effect (slope) of _HBG1_/_2_ proximal promoter edits on _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA expression, with an increasing effect (slope) on _HBB_ mRNA expression as the

BCL11A allelic series is increased. As expected, when modeling _HBB_ mRNA expression versus these same fixed and random effects, we find a similar, albeit moderated, result consistent with

the total levels of β-globin chains staying roughly in balance (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 12). This finding provides functional validation for the previously characterized binding

interaction of BCL11A with these elements (Supplementary Fig. 1b)15,25. We then sought to combine perturbation of the _HBB-_3.5kb element, which is commonly removed in HPFH deletions, with

BCL11A. By combining these edits in single hematopoietic progenitors and deriving erythroblasts in colony assays, we again observed a non-additive effect, suggestive of a functional

interaction across a range of genotypes (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 12). We again utilized LMMs to demonstrate a similar antagonistic interaction effect (_β_ = −0.15; _P_ value <

0.001) between the _HBB_-3.5 kb deletion and BCL11A perturbation (across the full allelic series involving perturbation of exons 2 or 4) upon _HBG1_/_2_ and _HBB_ mRNA expression. This

finding could readily be visualized by the decreasing effect (slope) of the _HBB_-3.5 kb edits on both _HBG1_/_2_ and _HBB_ mRNA expression as the BCL11A allelic series increases (Fig. 2f).

While these elements have been hypothesized to be critical for BCL11A-mediated silencing17, we now directly and quantitatively demonstrate at a functional level that BCL11A and this

long-range regulatory element must intersect. We next combined perturbation of the _HBB_-3.5kb element with ZBTB7A, the latter of which is primarily suggested to act in a local autonomous

manner to mediate _HBG1_/_2_ silencing25. Interestingly, we observed significant attenuation of the _HBG1_/_2_ induction caused by ZBTB7A perturbation upon concomitant perturbation of the

_HBB_-3.5kb element (Fig. 3a–c), which could be quantified using the LMM (_β_ = −0.75410; _P_ value <0.0001). This finding demonstrates that ZBTB7A also acts through both local and

long-range interactions to silence HbF. This prompted us to examine whether BCL11A and ZBTB7A were acting independently using our single-cell functional assay. Indeed, with combined

perturbations of both _trans_-acting factors, we observed independent induction of _HBG1_/_2_ expression, which could be demonstrated with the LMM and demonstration of completely parallel

lines in the visualization of this model (Fig. 3d–f; _β_ = 0.16148; _P_ value = 0.0623). Collectively, our findings therefore suggest that BCL11A has a critical functional role in enabling

silencing via two distinct genetically nominated _cis_-regulatory elements: the local _HBG1_/_2_ promoters and distal regulatory elements upstream of the _HBD_ gene. ZBTB7A also appears to

have roles in both local silencing of the _HBG1_/_2_ genes and in interaction with long-range regulatory elements. To gain further insights, we would ideally combine perturbations of these

two distinct _cis_-regulatory elements at the β-globin locus to also assess functional interactions. However, we found that tandem perturbations involving simultaneous introduction of 3–4

gRNAs primarily resulted in larger deletions of the entire _HBG1_/_2_ to _HBB_ region, preventing this analysis. ANALYSIS OF DISTINCT Β-GLOBIN LOCUS _CIS_-REGULATORY ELEMENTS AND BCL11A

DEPENDENCE USING CAPTURE AND 3C ASSAYS We next sought to integrate the results obtained from our single-cell functional assay of globin gene regulation with insights from systematic

biochemical assessments of long-range DNA interactions observed at critical mutation-associated _cis_-regulatory elements within the β-globin locus. Long-range chromatin interactions

including enhancer–promoter looping play causative roles in transcriptional activation, as demonstrated by induced loop formation at the β-globin locus33,34. The biotinylated dCas9-based

CAPTURE method enables the dissection of long-range DNA interactions at native chromatin that play critical roles in transcriptional regulation21,22. Given the need for significant cell

numbers to achieve high-resolution multiplexed CAPTURE analyses, we initially used HUDEP-2 cells that harbor an adult-like globin expression pattern and targeted knockout of BCL11A in these

experiments that results in predominant expression of _HBG1_/_2_15 (Supplementary Fig. 13). Using this approach, we engineered WT or BCL11A knockout HUDEP-2 cells co-expressing C-terminally

biotinylated dCas9 and multiplexed single gRNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the _HBB_, _HBG1_/_2_, _HBD_-3.5kb, and upstream enhancer LCR (harboring hypersensitive sites (HS), 1–5) (Fig. 4). As

expected, given the greatly reduced _HBB_ mRNA expression upon BCL11A knockout, we observed decreased long-range DNA interactions between the LCR HS1–5 and _HBB_ promoter upon this knockout

with concomitantly increased interactions between the LCR and _HBG1_/_2_ promoters (Fig. 4a, b). Remarkably, strong interactions observed in the adult globin expressing state between the

silenced _HBG1_/_2_ genes and the _HBD_-3.5kb region were completely abrogated upon deletion of BCL11A (Fig. 5a, b). These findings are concordant with the functional interaction observed

between BCL11A and the _HBD_-3.5kb upstream element in HbF silencing from our single-cell analysis. These findings were further corroborated by using the _HBD_-3.5kb region as the capture

bait region (Fig. 4c, d). We observed markedly reduced chromatin interactions between the _HBD_-3.5kb region and the _HBG1_/_2_ promoters, illustrating loss or destabilized long-range

chromatin interactions between _HBD-_3.5kb and _HBG1_/_2_ in the absence of BCL11A. Of note, _HBD-_3.5kb region had significantly more long-range chromatin interactions than other

_cis_-regulatory elements within the β-globin locus in WT HUDEP-2 cells, consistent with previous reports21,22. Importantly, the majority of these _HBD_-3.5kb region-mediated long-range

interactions were lost or significantly weakened in BCL11A knockout cells, suggesting that BCL11A is required for the maintenance of proper three-dimensional (3D) organization of the

β-globin locus to facilitate _HBB_ transcription. Interestingly, increased interactions of both the _HBG1_/_2_ regions and the _HBD_-3.5kb upstream element with the 3’ HS1 were noted upon

knockout of BCL11A (Fig. 4a–d). This suggests that there is global reorganization and long-range alterations in chromatin conformation seen upon knockout of BCL11A. In addition, by using the

LCR HS1–5 as the capture baits, we found markedly decreased interactions between the LCR and _HBD_-3.5kb region in BCL11A knockout cells (Fig. 4e, f), consistent with the results obtained

using the reciprocal _HBD_-3.5kb region as the capture bait (Fig. 4c, d). These results suggest that the 3D configuration mediated by long-range chromatin interactions between LCR and

_HBD_-3.5kb elements were impaired upon loss of BCL11A. Importantly, we noted decreased interactions between the LCR and the _HBB_ gene and increased interactions between the LCR and the

_HBG1_/_2_ genes (Fig. 4e, f), consistent with shifts in globin mRNA expression patterns observed upon BCL11A knockout (Supplementary Fig. 13c, d). To ensure that these interaction losses

were also observed in primary erythroid cells upon perturbation of BCL11A, we performed genome editing of BCL11A followed by 3C assays in bulk human HSPC-derived erythroblasts, which

revealed loss of the key interactions between the _HBD_-3.5kb region and the _HBG1_/_2_ promoters with concomitantly increased interaction between the LCR and _HBG1_/_2_ promoters upon

perturbation of BCL11A (Fig. 5a–c). The insights from the biochemical interaction data obtained through CAPTURE and 3C assays complement the data obtained through our single-cell functional

assessments, enabling the derivation of a unified model of HbF regulation based on human genetic observations (Fig. 5d, e). Specifically, our findings suggest at both a functional level and

through complementary biochemical assessments that two distinct genetically nominated _cis_-regulatory regions, the _HBG1_/_2_ proximal promoters and the _HBD_ 3.5 kb upstream region,

physically interact at native chromatin through long-range DNA interactions and act collaboratively with BCL11A to silence HbF expression. Upon targeted perturbation of either of these

elements or BCL11A, we see derepression of HbF silencing that is accompanied by dissociation of the locus-regulating chromatin interactions mediated by these elements. Importantly, in this

unified model, we distinguish the long-range interactions mediated by BCL11A and ZBTB7A, as well as the associated _cis_-elements with the local and independent silencing of the _HBG1_/_2_

genes by these factors. Hence, our findings establish evidence for the model that different _HBG1_/_2_-regulating _cis_-regulatory elements physically and functionally interact in 3D space

to coordinate chromatin structure and gene transcription, providing a clearer picture of how distinct elements nominated through human genetic studies of HbF variation may function

cooperatively in native biological contexts. DISCUSSION Here we have developed and utilized a single-cell functional assay with targeted genome editing in primary human HSPCs to mimic

perturbations that are observed in vivo in humans. We sought to use these targeted perturbations to gain a more complete picture of the regulation of HbF, a key therapeutic target for the

major disorders of β-hemoglobin, sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia2,35. While targeted perturbations of the 13 bp element in the _HBG1_/_2_ promoters, the 3.5 kb region upstream of

_HBD_, _BCL11A_, and _ZBTB7A_ have been individually studied, how all of these distinct genetically-nominated perturbations may function together has remained unknown. Through the use of

individual and combined perturbations, along with quantitative modeling of this data, we have now refined our understanding of this process. We are able to show that BCL11A has two major

functions to enable effective HbF silencing: acting “locally” and through “distal” interactions. We show that the local function of BCL11A enables silencing of the _HBG1_/_2_ genes via

promoter interactions involving the 13 bp element in a semi-autonomous manner, as has been recently shown to involve direct promoter occupancy and competition with the activating

transcription factor NF-Y15,25. In addition, we also demonstrate a key role for distal long-range interactions involving a functional region upstream of the _HBD_ gene that enables effective

HbF silencing17. While this _HBD_ upstream region has been posited to require BCL11A, originally through the suggested occupancy of this factor in this region, it has been unclear whether

this region is functionally required for HbF silencing. Through our functional assays in single progenitors and CAPTURE data, we show that long-range chromatin organization involving this

region requires intact BCL11A activity. While the precise underlying mechanisms that account for this distal activity remain to be fully defined, particularly given the variable observed

binding from recent CUT&RUN or chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing studies of BCL11A in this region15,25 (Supplementary Fig. 1b), a key role for BCL11A activity is clearly present.

Importantly, we also demonstrate distinct and non-overlapping roles for ZBTB7A in HbF silencing and a surprisingly strong negative interaction between its perturbation and the _HBB_-3.5kb

deletion. Collectively, our findings lead to a unified model of how distinct mutations may in aggregate contribute to the silencing of HbF and how BCL11A has dual activities to effectively

silence HbF through both local promoter interactions and long-range distal modulation of chromatin conformation at this locus (Fig. 5d, e). An important area for future studies will be to

tease apart whether overlapping or separable activities of BCL11A are required for these distinct roles involved in regulating HbF. A deeper understanding of this process holds significant

promise for the development of improved and more effective therapeutic approaches to induce HbF in sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Moreover, such complex long-range interactions

suggest a reason why only select approaches can successfully reconfigure chromatin interactions and gene expression at this locus33. While we have gained important insights through our

analysis, there are also several limitations that should be noted about these results. First, we have focused on mimicking perturbations highlighted by rare in vivo observations in humans.

Our rationale was based on the fact that these particular elements have been definitively shown to have a significant role in HbF silencing in humans. While other factors and elements have

been suggested to be involved in this process, we have not examined these here, since our focus was to understand how various in vivo perturbations may cooperatively function in the process

of HbF silencing. For instance, a set of long-range interactions with a region upstream of the _HBD_-3.5kb element within the _HBBP1_ pseudogene and also involving the _BGLT3_ non-coding RNA

have been suggested to have roles in HbF silencing36,37. Future studies taking advantage of similar kinds of approaches as we describe here will enable further insights and provide an

opportunity to examine the role of other _trans_- and _cis_-acting regulators through perturbation in single cells. Second, we do note limitations of the single progenitor functional assay

we describe. Most notably, the baseline level of _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA expression observed in this assay is higher than what is observed in vivo. This reinforces our focus on perturbations where

the effects can be compared to what is seen in vivo in the setting of individual perturbations. While the resultant levels of individual perturbations were larger than what is observed in

vivo in humans, the overall degree of HbF induction does closely mimic what is observed in individuals with these rare mutations, providing confidence in this approach. Third, we are

constrained by specific genome edits that can readily be achieved through existing genome-editing tools. This has limited our ability to combinatorially target in _cis_ multiple regulatory

elements within the β-globin locus. As improved genome perturbation and editing tools are developed, such as base and prime editors38, it is likely that refined assessment of distinct

perturbations, including the enumerable SNVs linked to this process, can be uncovered. Finally, our findings also have broader implications for how we should consider the multifactorial

impact of genetic variation. We have traditionally focused on the impact of individual variants either uncovered through studies of rare diseases or complex traits. This has enabled

previously unappreciated knowledge and emphasized the key role of non-coding regulatory variation. However, many questions remain about how numerous variants collectively act to impact a

phenotype of interest39,40. Through our studies of HbF regulation—a simple and directly measured quantitative trait impacted by human genetic variation—we have shown how studies of

combinatorial variation can reveal synergistic interactions that move beyond the conventional additive models employed to study human genetic variation. As increasing numbers of common

variants underlying complex diseases are uncovered, approaches combining single-cell functional interrogation and locus-specific chromatin interaction assays, as we use here, are likely to

provide insights into how combinations of genetic variants can act in non-additive ways to modulate the 3D genome in human health and disease41,42. METHODS PRIMARY HSPC CULTURE AND

COLONY-FORMING CELL ASSAY Human HSPCs from healthy donors (CD34 enriched) were obtained from the Fred Hutchinson Hematopoietic Cell Processing and Repository (Seattle, USA). Use of

deidentified human HSPCs was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital. The HSPCs were thawed and cultured in phase I erythroid differentiation Medium (EDM)

composed of Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, Life Technologies) supplemented with 200 μg/mL human holo-transferrin, 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin, 3 IU/mL heparin, 2% human AB

plasma, 3% human AB serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) with three supplemental cytokines (3 IU/mL erythropoietin (EPO), 10 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 1 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3)) at

37 °C and 5% CO243,44,45. For colony-forming cell assays, HSPCs were plated at 500 cells/mL in MethoCult H4034 Optimum methylcellulose medium (StemCell Technologies, Inc.) that support

erythroid maturation, along with formation of other hematopoietic colony types. Individual BFU-E colonies were identified by the distinct red color and morphology, which separates these

cells from other hematopoietic colonies. The cells in the BFU-E colonies were picked at day 14 after plating. CRISPR/CAS9 GENOME EDITING IN HSPCS gRNA sequences (shown in Supplementary Data

3) were chosen using the IDT CRISPR design tool and generated as oligonucleotides. The Amaxa Nucleofector System with program DZ-100 was used to deliver Cas9 and gRNA as a ribonucleoprotein

(RNP) complex into HSPCs. In all, 5 µL of 120 pmol gRNA duplex (crRNA:tracrRNA) and 105 pmol Cas9 protein (Integrated DNA Technologies, following the manufacturer’s instructions) were

prepared to form RNP complexes and delivered in 20 µL of 2–4 × 105 HSPCs using the P3 Primary Cell 4D Nucleofector X Kit S (Lonza, following the manufacturer’s instructions). Subsequently,

cells were transferred to phase I EDM culture medium for 24 h and then seeded in MethoCult H4034 Optimum methylcellulose medium (StemCell Technologies, Inc.). For long-range deletions

(_HBB_-3.5kb, _HBB_-_HBD_, _HBD_-3.5kb), paired gRNAs were delivered into HSPC following colony-forming cell assay. To generate combinatorial perturbations of _cis_-regulatory regions

(_HBB_-3.5kb, _HBG1_/_2_-∆13bp) and _trans_-acting factors (_BCL11A_, _ZBTB7A_), multiplexed RNPs composing 2–3 gRNAs were simultaneously nucleofected into HSPCs. BFU-E colonies were

randomly selected and collected as a single group of cells after 2 weeks of culture in order to evaluate the genome-editing genotype and hemoglobin gene expression. DNA and RNA were

simultaneously isolated from single BFU-E colony using the ALLPrep DNA/RNA Micro Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from BFU-E colony-extracted RNA

using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences used for PCR screening and Sanger sequencing of gRNA editing efficiency are shown

in Supplementary Data 4. DETECTION OF GENOME-EDITING EVENTS To evaluate editing efficiency of gRNA, we performed PCR followed by Sanger sequencing and ICE Analysis

(https://ice.synthego.com/) to decompose insertion/deletion (indel) of editing outcomes. Genotypes of edited alleles were confirmed by comparing the sequence chromatogram from edited bulk

HSPCs to a control sequence chromatogram from WT HSPCs. These genotypes were also confirmed by independent massively parallel sequencing validation. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed

using SYBR green (BioRad) and primers (shown in Supplementary Data 5) to evaluate the frequency of deletion and inversion of target regions (_HBB_-3.5kb, _HBB_-_HBD_, _HBD_-3.5kb) and was

validated with deletions confirmed via orthogonal approaches. For genotyping of BFU-E colonies, CRISPR/Cas9 targeted loci (BCL11A exon 2 gRNA, BCL11A exon 4 gRNA, ZBTB7A gRNA, _HBG1_/_2_ 13

bp gRNA) were amplified using primers (shown in Supplementary Data 4) and the Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs) according to the protocol. Amplicons were sequenced for

genotyping using primers (shown in Supplementary Data 4). The intact _HBG1_/_2_ genetic loci were confirmed by qPCR using primers (shown in Supplementary Data 5). Mutation of >2 bp within

_HBG_-Δ13bp were considered disruptive mutations under the assumption that these edits overlapped with the characterized BCL11A-binding site. The deletion and inversion events (_HBB_-3.5kb,

_HBB_-_HBD_, _HBD_-3.5kb) were identified by qPCR using primers. qPCR primer sequences used for detection of genome-editing events are shown in Supplementary Data 5. GLOBIN GENE EXPRESSION

ANALYSIS For cDNA extracted from BFU-E colonies, qPCR was carried out using a 96-well plate on a CFX96 Real Time System (BioRad) with SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad). _HBB_ and _HBG1_/_2_

mRNA/cDNA expression levels were normalized with endogenous control _HBA1_/_2_ gene expression levels. Gene-specific primers used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Data 6. _HBG1_ and

_HBG2_ gene expression were identified by _HBG1_/_2_ expression level and _HBG1_:_HBG2_ expression ratio, which were calculated based on G (_HBG1_):A (_HBG2_) nucleotide ratios from the

Sanger sequencing chromatograms. PCR and sequencing primers are shown in Supplementary Data 6. ERYTHROID DIFFERENTIATION HSPCs were cultured and differentiated in a three-phase erythroid

differentiation culture system43,44,45. Briefly, cells were cultured in IMDM (Life Technologies) containing 200 μg/mL human holo-transferrin, 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin, 3 IU/mL

heparin, 2% human AB plasma, 3% human AB serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (base medium). In phase I (0–7 days), the cultures were supplemented with 3 IU/mL EPO, 10 ng/mL SCF, and 1

ng/mL IL-3 and in phase II (7–12 days) they were supplemented with 3 IU/mL EPO and 10 ng/mL SCF alone. In phase III (12–17 days), primary cell cultures contained 1 mg/mL of human

holo-transferrin supplemented with 3 IU/mL EPO. Cells were maintained at 105–106 per mL in phases I and II and at 1–5 × 106 per mL in phase III. Cells were changed into fresh culture medium

every 3 days. For assessment of differentiation, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with anti-human CD49d, CD71, and CD235a antibodies (shown in Supplementary

Data 10). Flow cytometric analyses were conducted on an Accuri C6 instrument and all data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (v.10.3). IMMUNOBLOT ANALYSIS Immunoblotting was performed

by following standard approaches45. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and protein levels were quantified with the DC Protein Assay (BioRad). Briefly, samples were

incubated at 95 °C for 5 min in 4× Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad) and loaded on to a Mini-Protein TGX Gel (BioRad) for electrophoresis at 120 V for 1 h. Proteins were then transferred to

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane with BioRad wet transfer system at 100 V for 1.5 h. Membranes were blocked with TBS-T/3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h and then incubated with primary

antibodies overnight in a cold room with shaking. Excess antibodies were washed with TBS-T (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Tween 20) for 3 times and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibodies were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After 3 washes with TBS-T, the membranes were developed with the Clarity Western ECL Substrate Kit (BioRad). Immunoblots

were performed with antibodies BCL11A (AbCam, at 1/1000 dilution), ZBTB7A (eBioscience, at 1/1000 dilution), Hemoglobin γ (Santa Cruz, 1/250 dilution), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz, at 1/5000 dilution). The secondary antibodies used were goat anti-rabbit (BioRad), goat anti-mouse (BioRad), and goat anti-hamster (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Data 9. The blotting intensities were analyzed using ImageJ (version 1.8.0). RNA ISOLATION AND QPCR WITH REVERSE TRANSCRIPTION (RT-QPCR) In all, 1 ×

106 HSPC-derived erythroblasts were collected and isolated for RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNAse (Qiagen) digestion, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

cDNA was synthesized with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). RT-qPCR was carried out using a 96-well plate on a CFX96 Real Time System (BioRad) with SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad).

Gene-specific primers used for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Data 6. HBF FLOW CYTOMETRY For HbF analysis cells were fixed in 0.05% glutaraldehyde for 10 min, washed 2 times with

PBS/0.1% BSA (Sigma), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Life Technologies, prepared in PBS/0.1% BSA) for 5 min. Following one wash with PBS/0.1% BSA, cells were stained with HbF-APC

conjugate antibody (Invitrogen). For primary erythroid cells, 5 × 105 cells were incubated with 0.4 µg HbF-APC antibody (shown in Supplementary Data 10) for 10 min in the dark at room

temperature. Cells were then washed twice with PBS/0.1% BSA. Flow cytometric analyses were conducted on an Accuri C6 instrument, and all data were analyzed using the FlowJo software

(v.10.3). HEMOGLOBIN HPLC Approximately 5 × 106 erythroblasts were collected on day 17 of erythroid differentiation and subjected to lysis for hemoglobin high-performance liquid

chromatography (HPLC). HbF levels were measured using a G7 HPLC Analyzer (Tosoh Bioscience, Inc.) with the β-thalassemia program. To compare HbF levels across experiments, we defined HbF% as

a proportion of HbF relative to HbA and other hemoglobin subtypes. HUDEP-2 CELL CULTURE HUDEP-2 cells were maintained in expansion medium: StemSpan SFEM (STEMCELL Technologies) with 50

ng/mL SCF, 3 IU/mL EPO, 10−6 M dexamethasone, and 1 μg/mL doxycycline and passaged every 3 days. The cell density was maintained within 20,000–500,000 cells/mL. Erythroid differentiation was

carried out by replacing the medium to EDM (IMDM; Corning) supplemented with 330 μg/mL human holo-transferrin, 10 μg/mL recombinant human insulin, 2 IU/mL heparin, 5% heat-inactivated

plasma, 3 IU/mL EPO, 2 mM L-glutamine) with two supplements (100 ng/mL SCF, 1 μg/mL doxycycline). After 5 days of differentiation, cells were collected for CAPTURE analyses. BIOTINYLATED

DCAS9-MEDIATED CAPTURE ASSAYS HUDEP-2 cells co-expressing Bio-tagged dCas9 (CAPTURE2.0-CBio) and sequence-specific sgRNAs were generated as previously described with modifications21,22.

CAPTURE-3C-seq experiments were performed as previously described using between 3 and 5 million WT or BCL11A knockout HUDEP-2 cells21,22. CAPTURE-3C-seq data processing and quantitative

analyses of locus-specific long-range DNA interactions were performed as previously described21,22. Three biological replicates were merged for WT or BCL11A knockout HUDEP-2 cells,

respectively. Only significant long-range DNA interactions from the following captured bait regions with BF score ≥20 were used for quantitative analyses: _HBB_, _HBG1_/_2_, _HBD_-3.5kb

(containing sgRNAs targeting _HBD_-1kb, _HBD_-1.5kb, and _HBD_-3.5kb regions), and upstream enhancer locus control (HS1–5) regions. The relative interaction frequency per kilobase at each

captured bait region was calculated as (interactions between bait region and other interacting regions) × 106/(size of bait region × all interactions from bait region). The computer code for

data processing and analysis is available from GitHub (https://github.com/ChenYong-RU/MAXIM). CHROMOSOME CONFORMATION CAPTURE 3C was performed as described previously46. Briefly, 1 × 107

HSPC-derived cell nuclei (AAVS1 and BCL11A exon 2 gRNA) at day 12 of erythroid differentiation were fixed in 1% formaldehyde, digested with EcoRI overnight, and ligated for 4 h with T4 DNA

ligase at 16 °C. Cross-links were reversed and ligation products extensively purified. qPCR was performed using SYBR green (BioRad) and primers (shown in Supplementary Data 7) to evaluate

ligation products. Ligation frequencies were normalized to an interaction in the TUBA1A gene (shown in Supplementary Data 7). CREATION OF BCL11A DOMINANT-NEGATIVE MUTANTS All constructs of

BCL11A dominant-negative mutants incorporating 1 bp∆, 2 bp∆, and 7 bp∆ mutants of interest were created using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs). Primers used for

constructs are listed in Supplementary Data 8. For genotyping of BCL11A dominant-negative mutants, targeted loci were amplified using primers (shown in Supplementary Data 8) and the Q5

High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix (New England Biolabs) according to the protocol. Amplicons were sequenced for genotyping using primers (shown in Supplementary Data 8). LENTIVIRAL INFECTIONS

HSPCs undergoing erythroid differentiation were transduced with HMD control, BCL11A WT, and 1 bp∆, 2 bp∆, and 7 bp∆ lentiviral constructs on day 2 of differentiation; 293T cells for

lentivirus production were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Approximately 24 h before transfection, 293T cells were seeded,

without antibiotics, in 6-well plates. Cells were co-transfected with the packaging vectors pVSVG and pΔ8.9 and the lentiviral genomic vector of interest. The medium was changed to base

medium on the day following transfection, and the viral supernatant was collected approximately 48 h post-transfection, filtered with a 0.45-μm filter, and used for infection of CD34+ cells.

Where the virus was required to be concentrated, 293T cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes and the viral supernatant was filtered and centrifuged at 64,512 × _g_ for 2 h at 4 °C. Between

200,000 and 300,000 CD34+ cells were infected in 6-well plates with 8 μg/mL of polybrene (Millipore), spun at 448 × _g_ for 1.5 h at room temperature, and incubated in the viral supernatant

overnight at 37 °C. Virus was washed off 1 day after infection, and infected cells were selected for by green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression driven by IRES-GFP in the HMD vector in the

particular construct. GFP+ cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting in a sterile manner and cultured for further analysis. Flow cytometric analyses were conducted on Becton

Dickinson LSRII, and data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (v.10.3). STATISTICAL ANALYSES AND QUANTITATIVE MODELING Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.16), GraphPad

Prism 7, FlowJo (version 10.3), ImageJ (version 1.8.0), and R (version 3.4.3). Statistical analysis of data was generally done using the two-tailed Student’s _t_ test, unless otherwise

specified. Detailed information about statistical methods are specified in figure legends or in specific parts of the “Methods” section. In order to quantitatively model HbF expression, we

separated this measurement into _HBB_ and _HBG1_/_2_ mRNA expression and fit these values using a LMM. Edited genotypes were coded as either editing events (0–2) for the _HBB_-_HBD_,

_HBD_-3.5kb, the combined deletion _HBB_-3.5kb, and _ZBTB7A_ or as an allelic series for _HBG1_/_2_ (0–4) and _BCL11A_ (0–3) and treated as fixed effects in these models. Interaction effects

between the edits were also treated as fixed effects. Three models with differing fixed effects were used in order to maximize numeric observations and to explore meaningful genetic

interactions: (1) _HBB_-_HBD_, _HBD_-3.5kb, and their interaction; (2) _HBB_-3.5kb, _HBG1_/_2_, and _BCL11A_ with applicable interaction terms; and (3) _HBB_-3.5kb, _ZBTB7A_, and _BCL11A_

and applicable interaction terms. In order to account for differences in the unedited states between conditions, we allowed for random intercepts based on the gRNAs introduced in each

condition, as well as the specific cell donor when applicable. Thus, the LMMs fit the equation: $${y}={X}\beta +{Z}\mu +{\epsilon }$$ (1) where _y_ is _n_ × 1 column vector of _HBB_ or

_HBG1_/_2_ mRNA measurements, _X_ is a _n_ × number of deletions + interaction terms matrix of fixed effects (_p_), _β_ is a _p_ × 1 row vector of the _β_-coefficients of the fixed effects,

_Z_ is an _n_ × number of donors + number of gRNAs, which affect either _HBB_ or _HBG1_/_2_ basal levels (doubled for the presence or absence of the gRNA) model matrix of random effects, and

_ε_ is _n_ × 1 residual column vector of the residuals. LMM was performed using the R package lme4. _P_ values for fixed effects were approximated using the Satterthwaite method

instantiated through the lmerTest package. We do note that large confidence intervals were noted in some cases, particularly at the end of the allelic spectrum involving multiple

edits/perturbations due to limited numbers of colonies of a particular genotype assessed. All resultant _β_ and corresponding _P_ values are provided in the text as each analysis is

discussed. Data were visualized in R using the sjPlot and ggplot2 packages. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary

linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The original data for globin gene expression analysis in BFU-E has been provided as a Supplementary File. Raw immunoblots for Supplementary Figs.

7b, 8d, and 10b are available online. CAPTURE data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE181151. All previously published

datasets used in this paper are available at the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and relevant accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Data 2. Source data are

provided with this paper. CODE AVAILABILITY Custom computational code for reproduction of statistical analyses and quantitative modeling is available at

https://github.com/sankaranlab/Fetal_Hemoglobin_model. REFERENCES * Sankaran, V. G. & Orkin, S. H. The switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin. _Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med._ 3,

a011643 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Tisdale, J. F., Thein, S. L. & Eaton, W. A. Treating sickle cell anemia. _Science_ 367, 1198–1199 (2020). Article

ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Furlong, E. E. M. & Levine, M. Developmental enhancers and chromosome topology. _Science_ 361, 1341–1345 (2018). Article ADS CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Menzel, S. et al. A QTL influencing F cell production maps to a gene encoding a zinc-finger protein on chromosome 2p15. _Nat. Genet._ 39, 1197–1199

(2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Uda, M. et al. Genome-wide association study shows BCL11A associated with persistent fetal hemoglobin and amelioration of the phenotype of

beta-thalassemia. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 105, 1620–1625 (2008). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sankaran, V. G. et al. Human fetal hemoglobin expression is

regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. _Science_ 322, 1839–1842 (2008). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bauer, D. E. et al. An erythroid enhancer of

BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. _Science_ 342, 253–257 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Basak, A. et al. BCL11A

deletions result in fetal hemoglobin persistence and neurodevelopmental alterations. _J. Clin. Investig._ 125, 2363–2368 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Funnell,

A. P. W. et al. 2p15-p16.1 microdeletions encompassing and proximal to BCL11A are associated with elevated HbF in addition to neurologic impairment. _Blood_ 126, 89–93 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dias, C. et al. BCL11A haploinsufficiency causes an intellectual disability syndrome and dysregulates transcription. _Am. J. Hum. Genet._ 99,

253–274 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Giardine, B. et al. Updates of the HbVar database of human hemoglobin variants and thalassemia mutations. _Nucleic

Acids Res._ 42, D1063–D1069 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Giardine, B. et al. Systematic documentation and analysis of human genetic variation in hemoglobinopathies using

the microattribution approach. _Nat. Genet._ 43, 295–301 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Martyn, G. E. et al. A natural regulatory mutation in the proximal promoter elevates

fetal expression by creating a de novo GATA1 site. _Blood_ 133, 852–856 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Masuda, T. et al. Transcription factors LRF and BCL11A independently

repress expression of fetal hemoglobin. _Science_ 351, 285–289 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, N. et al. Direct promoter repression by BCL11A

controls the fetal to adult hemoglobin switch. _Cell_ 173, 430.e17–442.e17 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, N. et al. Transcription factor competition at the γ-globin promoters

controls hemoglobin switching. _Nat. Genet_. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00798-y (2021). * Sankaran, V. G. et al. A functional element necessary for fetal hemoglobin silencing. _N.

Engl. J. Med._ 365, 807–814 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Antoniani, C. et al. Induction of fetal hemoglobin synthesis by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of

the human β-globin locus. _Blood_ 131, 1960–1973 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ghedira, E. S. et al. Estimation of the difference in HbF expression due to loss of the 5’

δ-globin BCL11A binding region. _Haematologica_ 98, 305–308 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Porteus, M. H. A new class of medicines through DNA editing. _N.

Engl. J. Med._ 380, 947–959 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, X. et al. In situ capture of chromatin interactions by biotinylated dCas9. _Cell_ 170, 1028.e19–1043.e19

(2017). Google Scholar * Liu, X. et al. Multiplexed capture of spatial configuration and temporal dynamics of locus-specific 3D chromatin by biotinylated dCas9. _Genome Biol._ 21, 59

(2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dulmovits, B. M., Hom, J., Narla, A., Mohandas, N. & Blanc, L. Characterization, regulation, and targeting of erythroid

progenitors in normal and disordered human erythropoiesis. _Curr. Opin. Hematol._ 24, 159–166 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ludwig, L. S. et al. Lineage

tracing in humans enabled by mitochondrial mutations and single-cell genomics. _Cell_ 176, 1325–1339.e22 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Martyn, G. E. et al.

Natural regulatory mutations elevate the fetal globin gene via disruption of BCL11A or ZBTB7A binding. _Nat. Genet._ 50, 498–503 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Traxler, E.

A. et al. A genome-editing strategy to treat β-hemoglobinopathies that recapitulates a mutation associated with a benign genetic condition. _Nat. Med._ 22, 987–990 (2016). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gilman, J. G. et al. Distal CCAAT box deletion in the A gamma globin gene of two black adolescents with elevated fetal A gamma globin. _Nucleic

Acids Res._ 16, 10635–10642 (1988). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bak, R. O. et al. Multiplexed genetic engineering of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

using CRISPR/Cas9 and AAV6. _Elife_ 6, e27873 (2017). * Liu, H. et al. Functional studies of BCL11A: characterization of the conserved BCL11A-XL splice variant and its interaction with BCL6

in nuclear paraspeckles of germinal center B cells. _Mol. Cancer_ 5, 18 (2006). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Xu, J. et al. Transcriptional silencing of

{gamma}-globin by BCL11A involves long-range interactions and cooperation with SOX6. _Genes Dev._ 24, 783–798 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yang, Y. et al.

Structural insights into the recognition of γ-globin gene promoter by BCL11A. _Cell Res._ 29, 960–963 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Maeda, T. et al. LRF is an

essential downstream target of GATA1 in erythroid development and regulates BIM-dependent apoptosis. _Dev. Cell_ 17, 527–540 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Deng, W. et al. Reactivation of developmentally silenced globin genes by forced chromatin looping. _Cell_ 158, 849–860 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Deng,

W. et al. Controlling long-range genomic interactions at a native locus by targeted tethering of a looping factor. _Cell_ 149, 1233–1244 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Sankaran, V. G. & Weiss, M. J. Anemia: progress in molecular mechanisms and therapies. _Nat. Med._ 21, 221–230 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Huang, P. et al. Comparative analysis of three-dimensional chromosomal architecture identifies a novel fetal hemoglobin regulatory element. _Genes Dev._ 31, 1704–1713 (2017). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ivaldi, M. S. et al. Fetal γ-globin genes are regulated by the long noncoding RNA locus. _Blood_ 132, 1963–1973 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Anzalone, A. V., Koblan, L. W. & Liu, D. R. Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 38,

824–844 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McGuire, A. L. et al. The road ahead in genetics and genomics. _Nat. Rev. Genet_. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0272-6 (2020). *

Chakravarti, A. & Turner, T. N. Revealing rate-limiting steps in complex disease biology: the crucial importance of studying rare, extreme-phenotype families. _Bioessays_ 38, 578–586

(2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * French, J. D. & Edwards, S. L. The role of noncoding variants in heritable disease. _Trends Genet_.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2020.07.004 (2020). * Liggett, L. A. & Sankaran, V. G. Unraveling hematopoiesis through the lens of genomics. _Cell_ 182, 1384–1400 (2020). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Giani, F. C. et al. Targeted application of human genetic variation can improve red blood cell production from stem cells. _Cell Stem Cell_ 18, 73–78 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nandakumar, S. K. et al. Gene-centric functional dissection of human genetic variation uncovers regulators of hematopoiesis. _Elife_ 8, e44080 (2019).

* Basak, A. et al. Control of human hemoglobin switching by LIN28B-mediated regulation of BCL11A translation. _Nat. Genet._ 52, 138–145 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kiefer, C. M. et al. Distinct Ldb1/NLI complexes orchestrate γ-globin repression and reactivation through ETO2 in human adult erythroid cells. _Blood_ 118, 6200–6208 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to members of the Sankaran laboratory for valuable guidance and suggestions. We

thank R. Rosales, G. Menard, and D. Dorfman for assistance with hemoglobin HPLC analyses. This work was supported by the New York Stem Cell Foundation (to V.G.S.), a gift from the Lodish

Family to Boston Children’s Hospital (to V.G.S.), and National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK103794 (to V.G.S.), R01 HL146500 (to V.G.S.), R56 DK125234 (to V.G.S.), R01CA230631 (to

J.X.), and R01DK111430 (to J.X.). J.X. is a Scholar of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. S.K.N. and J.X. are Scholars of the American Society of Hematology. V.G.S. is a New York Stem Cell

Foundation-Robertson Investigator. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Division of Hematology/Oncology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Yong

Shen, Jeffrey M. Verboon, Nan Liu, Samantha Marglous, Satish K. Nandakumar, Richard A. Voit, Claudia Fiorini, Ayesha Ejaz, Anindita Basak, Stuart H. Orkin & Vijay G. Sankaran *

Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Yong Shen, Jeffrey M. Verboon, Nan Liu, Samantha Marglous, Satish K. Nandakumar,

Richard A. Voit, Claudia Fiorini, Ayesha Ejaz, Anindita Basak, Stuart H. Orkin & Vijay G. Sankaran * Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA Yong Shen, Jeffrey M. Verboon,

Samantha Marglous, Satish K. Nandakumar, Richard A. Voit, Claudia Fiorini, Ayesha Ejaz, Anindita Basak & Vijay G. Sankaran * Children’s Medical Center Research Institute, Department of

Pediatrics, Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA Yuannyu Zhang, Yoon Jung Kim & Jian Xu * Harvard Stem Cell

Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA Samantha Marglous, Stuart H. Orkin & Vijay G. Sankaran * Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston, MA, USA Stuart H. Orkin Authors * Yong Shen View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jeffrey M. Verboon View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yuannyu

Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nan Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Yoon Jung Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Samantha Marglous View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Satish K. Nandakumar View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Richard A. Voit View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Claudia Fiorini View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ayesha Ejaz View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anindita Basak View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Stuart H. Orkin View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jian Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Vijay G. Sankaran

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Y.S. and V.G.S. conceptualized the study. Y.S., J.M.V., N.L. Y.Z., Y.J.K., J.X., and V.G.S.

developed methodology. Y.S., J.M.V., N.L., Y.Z., Y.J.K., S.M., and A.E. performed experiments. Y.S., J.M.V., N.L., Y.Z., Y.J.K., J.X., and V.G.S. analyzed experiments. Y.S., J.M.V., N.L.,

Y.Z., Y.J.K., S.K.N., R.A.V., C.F., A.B., S.H.O., J.X., and V.G.S. developed resources. Y.S., J.M.V., Y.Z., N.L., J.X., and V.G.S. wrote the original draft with input from all authors.

S.H.O., J.X., and V.G.S. supervised the project. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Vijay G. Sankaran. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Ross Hardison and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer

reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 2 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 3 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 4

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 5 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 6 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 7 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 8 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 9 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 10 REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any

medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Shen, Y., Verboon,

J.M., Zhang, Y. _et al._ A unified model of human hemoglobin switching through single-cell genome editing. _Nat Commun_ 12, 4991 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25298-9 Download

citation * Received: 26 April 2021 * Accepted: 02 August 2021 * Published: 17 August 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25298-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following

link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature

SharedIt content-sharing initiative