Plant species determine tidal wetland methane response to sea level rise

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Blue carbon (C) ecosystems are among the most effective C sinks of the biosphere, but methane (CH4) emissions can offset their climate cooling effect. Drivers of CH4 emissions from

blue C ecosystems and effects of global change are poorly understood. Here we test for the effects of sea level rise (SLR) and its interactions with elevated atmospheric CO2, eutrophication,

and plant community composition on CH4 emissions from an estuarine tidal wetland. Changes in CH4 emissions with SLR are primarily mediated by shifts in plant community composition and

associated plant traits that determine both the direction and magnitude of SLR effects on CH4 emissions. We furthermore show strong stimulation of CH4 emissions by elevated atmospheric CO2,

whereas effects of eutrophication are not significant. Overall, our findings demonstrate a high sensitivity of CH4 emissions to global change with important implications for modeling

greenhouse-gas dynamics of blue C ecosystems. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE CLIMATE BENEFIT OF SEAGRASS BLUE CARBON IS REDUCED BY METHANE FLUXES AND ENHANCED BY NITROUS OXIDE

FLUXES Article Open access 13 October 2023 METHANE EMISSIONS OFFSET ATMOSPHERIC CARBON DIOXIDE UPTAKE IN COASTAL MACROALGAE, MIXED VEGETATION AND SEDIMENT ECOSYSTEMS Article Open access 03

January 2023 GLOBAL METHANE EMISSIONS FROM RIVERS AND STREAMS Article Open access 16 August 2023 INTRODUCTION Tidal wetlands (i.e. marshes and mangroves) are often characterized by lower

emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas CH4 than nontidal wetlands1,2,3,4. Microbial CH4 production in wetland soils is governed by the balance of electron donors and terminal electron

acceptors5. Lower CH4 emissions in tidal vs. nontidal wetlands result from higher soil concentrations of sulfate, which acts as a terminal electron acceptor and allows sulfate-reducing

bacteria to outcompete methanogenic communities for electron donors5,6. Site salinity, a proxy for sulfate availability, is the best-established predictor of CH4 emissions from tidal

wetlands, but it weakly constrains emission rates6,7. Overall, CH4 emissions from tidal wetlands are extremely variable, and many sites emit CH4 at rates that exceed C sequestration in terms

of CO2 equivalents2,8,9. Drivers of variability in CH4 emissions other than sulfate are poorly understood7,10. Only few case studies have elucidated other important drivers of CH4

emissions, such as sedimentation dynamics11, organic matter quality and quantity7, tidal pumping12, and functional trait composition of plant communities13,14,15. Therefore, the consequences

of perturbations on radiative forcing from tidal wetlands are difficult to predict and often unknown, currently representing one of the biggest challenges in blue C science16. Global change

alters C sequestration and greenhouse-gas dynamics across ecosystems. In tidal wetlands, accelerated relative sea level rise (SLR) represents the overriding global change factor affecting

ecosystem function in the long-term17,18,19. Although SLR poses a major threat to the stability of tidal wetlands, it also enhances their C stocks globally by stimulating C sequestration in

soils18,20. SLR effects on tidal wetlands can therefore induce an important negative feedback to global warming20. Conversely, as SLR increases flooding frequency, leading to increasingly

anaerobic soil conditions, it also yields the potential to stimulate CH4 emissions. It is therefore possible that SLR-stimulated soil C sequestration is offset or even reversed by SLR

stimulation of CH4 emissions. Methane emissions from nontidal wetland ecosystems often increase in response to global change factors such as elevated atmospheric levels of CO2, rising

temperatures, and eutrophication21,22,23,24,25. Stimulated CH4 emissions in response to global change are often driven by the strong control of plant processes on soil CH4 dynamics. Plants

can stimulate CH4 emissions from soils by increasing the input of organic matter serving as electron donors. Particularly, the input of recent photo-assimilates to the soil via root

exudation is known to fuel methanogenic communities5,26. However, it is unclear if CH4 responses to commonly studied global change factors in nontidal wetlands are transferable to tidal

wetlands where SLR strongly interacts and often dominates other global change factors, modulating their effects on plant traits and microbial processes such as primary production and

decomposition18,27,28. We therefore argue that the overriding control of SLR on tidal wetland functioning needs to be considered when estimating the effects of other global change drivers on

CH4 emissions. The effects of SLR on CH4 emissions and the degree to which SLR modulates the effects of other global changes on CH4 emissions has never been studied and cannot easily be

projected. For instance, SLR-induced increases in flooding frequency are likely to exert opposing effects on the availability of two terminal electron acceptors that suppress methanogenesis,

namely sulfate and oxygen. In addition, the relationship between sea level and electron donor availability (i.e. plant productivity) is not linear29,30, further complicating projections of

CH4 dynamics in tidal wetlands. Here we investigate the effects of SLR and its interactions with elevated atmospheric CO2 and coastal eutrophication (i.e. elevated nitrogen levels) on CH4

emissions from an estuarine tidal wetland. Multifactorial manipulations were implemented by applying a unique experimental design that combines field-deployed marsh mesocosms for sea level

manipulation31 and floating open top chambers to control atmospheric CO2 concentrations27. Relationships observed in mesocosm studies were then tested against field data. We hypothesized

that CH4 emissions would increase in response to all factors—SLR, elevated CO2, and eutrophication—and that SLR would be the dominant factor because of the strong control it exerts on oxygen

availability. We predicted that CH4 emissions would rise monotonically with SLR, and be greater within a given sea level when CO2 or nitrogen were added as resources. We observed increases

in CH4 emissions in response to SLR and elevated CO2, but not to eutrophication. SLR indeed exerted the strongest control on CH4 emissions; however, its effect was nonlinear rather than

monotonic, initially decreasing with SLR before increasing with SLR. This unexpected pattern in CH4 emissions was primarily mediated by SLR-driven shifts in plant community composition that

determined both the direction and magnitude of the CH4 response. Subsequent in-situ observations confirmed that the same pattern occurs at the field-plot scale. Our findings therefore

demonstrate that predictions of current and future greenhouse-gas dynamics of blue C ecosystems will require understanding of plant community dynamics and traits relevant to CH4 cycling.

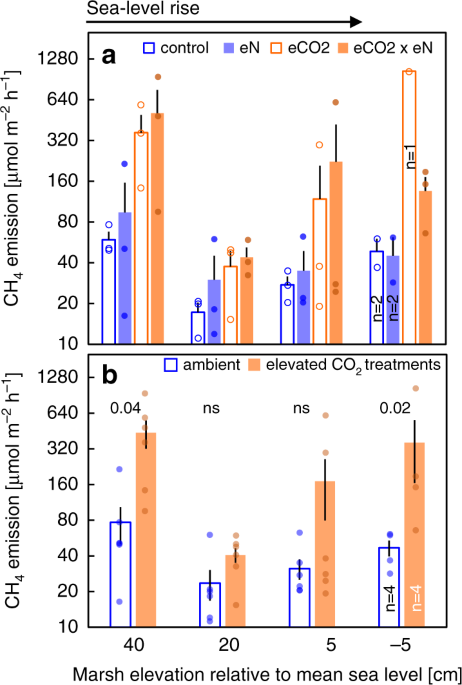

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION MULTIPLE GLOBAL CHANGE EFFECTS ON CH4 EMISSIONS Global change treatments (sea level × nitrogen fertilization × elevated CO2) were applied in a full-factorial design,

and effects were analyzed using three-way (split plot) ANOVA27 (Experiment 1). Sea level manipulations exerted the strongest effect on CH4 emissions (_F_ = 10.78; _p_ ≤ 0.001; Table 1; Fig.

1). The effect of relative sea level was nonlinear, counter to the expectation that increasing flooding will monotonically increase CH4 emissions. CH4 emissions were greatest at +40 cm above

mean sea level (MSL; least-flooded elevation), show a steep drop from +40 cm to +20 cm above MSL, then increase from +20 cm to –5 cm (most-flooded elevation). Emissions from the least- and

most-flooded elevations were not significantly different (Fig. 2a). Nonlinear regression analysis suggests a unimodal relationship between sea level and CH4 emissions (log CH4 emissions

(MSL) = 0.001_x_2 − 0.04_x_ + 1.78; _R_2 = 0.30; _p_ ≤ 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 1). The nitrogen fertilization treatment and any interactions thereof did not affect CH4 emissions (all _F_

values ≤ 0.65; all _p_ values ≥ 0.59; Table 1; Fig. 1a). By contrast, an apparent CO2 effect was indicated (_F_ = 5.84; _p_ = 0.07; Table 1), but likely masked to a certain degree by the

overriding effect of the sea level treatment on our results. Indeed, two-way analyses within sea level treatments confirmed significant and strong stimulation of CH4 emissions by elevated

CO2, with mean stimulation ranging from 70% at +20 cm to 670% at −5 cm relative to MSL (Fig. 1b). SPECIES SHIFTS CONTROL GLOBAL CHANGE EFFECTS ON CH4 EMISSIONS Experiment 1 was designed to

examine the effects of interacting global change factors on plant growth in the context of interspecific competition27, and therefore global change treatments were applied to realistic plant

assemblages, not single species. Plant responses of the two dominant species, the C4 grass _Spartina patens_ (hereafter _Spartina_) and the C3 sedge _Schoenoplectus americanus_ (hereafter

_Schoenoplectus_), to sea level treatments reflected their abundance and biomass allocation along the natural elevation gradient and the SLR-driven encroachment of flooding tolerant

_Schoenoplectus_ into _Spartina_ communities of the adjacent reference marsh and elsewhere27,29,32,33,34 (Fig. 2b, compare Langley et al.27 for a detailed presentation of plant biomass

responses). Here we found an unforeseen sharp decrease in CH4 emissions with rising sea level in the higher parts of the tidal frame (Fig. 2a). This result was unexpected, because soil

oxygen availability should have decreased as flooding duration increased from high to low elevations27,35, simultaneously enhancing methanogenesis and suppressing methanotrophy. In the

following we argue that the observed decrease in CH4 emissions was driven by a shift in species dominance from _Spartina_, dominant at high elevations of the marsh, to _Schoenoplectus_,

dominant at low elevations (Fig. 2b). CH4 emissions were inversely related to _Schoenoplectus_ aboveground biomass across all treatment combinations (log CH4 emissions = −0.0004_x_ + 2.307;

_R_2 = 0.144; _p_ ≤ 0.01). Relationships between biomass parameters and CH4 emissions were much stronger when restricted to certain CO2- and nitrogen-treatment combinations. Specifically,

CH4 emissions showed the strongest negative relation to _Schoenoplectus_ aboveground biomass within ambient CO2-treatment combinations (Fig. 3), although similar but weaker relationships

were also found under elevated CO2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The opposite response was observed in relation to _Spartina_ aboveground biomass, which scaled positively with CH4 emissions under

ambient CO2 (Fig. 3). Relationships between biomass parameters and CH4 emissions were strongest when the dataset was restricted to the highest (least flooded) two treatments (+40 cm and +20

cm above MSL; Fig. 3), where changes in CH4 emissions were most pronounced (Fig. 2a) and dominance of the two species was most balanced (Fig. 2b). Relationships of CH4 emissions with plant

parameters other than aboveground biomass were not significant, neither across nor within treatment groups (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Plot-scale CH4 data from the adjacent Smithsonian

Global Change Research Wetland (GCReW) support the mesocosm results. Mean growing season CH4 emissions were strongly related to the relative abundance of the two species (Fig. 4) and over

three times greater from the higher elevation _Spartina_-dominated community of the marsh (65 ± 37 µmol m−2 h−1) than from the lower elevation _Schoenoplectus_-dominated community (20 ± 5

µmol m−2 h−1; _p_ ≤ 0.05; _n_ = 3). Both absolute CH4 emission rates and differences induced by community composition correspond well to the findings of Experiment 1 (Fig. 1a, control

treatment). In order to evaluate the importance of these plant species-specific effects in mediating the relationship between sea level and CH4 emissions in the upper tidal frame, a

follow-up marsh organ experiment was conducted (Experiment 2). Experiment 2 did not use mixed species assemblages as in Experiment 1, but instead used pure communities of _Schoenoplectus_ or

_Spartina_ to isolate species-level effects at two different sea levels. CH4 emissions between the two species were dramatically different. Mean CH4 emissions were 55 and 65 times greater

from _Spartina_ compared to _Schoenoplectus_ at +15 cm and +35 cm above MSL, respectively (_F_ = 40.80; _p_ ≤ 0.001; Fig. 2c). Sea level (_F_ = 1.43; _p_ = 0.26) and the interaction of sea

level and plant species (_F_ = 0.20; _p_ = 0.66) did not affect CH4 emissions (Fig. 2c) demonstrating that CH4 emissions as a function of sea level are primarily mediated by shifts in plant

species composition, and that the direct (i.e. non-plant mediated) control of sea level on electron acceptor availability, such as oxygen, iron, and sulfate, is of less importance. In

contrast to the clear effects of sea level on _Spartina_ vs. _Schoenoplectus_ dominance in Experiment 1, CO2 and nitrogen treatments did not induce significant shifts in species dominance

within the mixed communities27, demonstrating the stronger control of sea level than other global change factors on species composition. Both CO2 and nitrogen treatments produced positive

effects on plant biomass27, but these did not translate into changes in CH4 emissions. Nitrogen fertilization strongly and consistently increased _Schoenoplectus_ and _Spartina_ biomass

across elevations27 but had no effect on CH4 emissions (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). Elevated CO2 significantly increased _Schoenoplectus_ and total aboveground biomass27, two factors that were

negatively related to CH4 emissions (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2), implying that the strong and positive effect of elevated CO2 on CH4 emissions (Fig. 1) was driven by plant processes

that are not directly linked to biomass. One likely process is the well-documented phenomenon of increased root exudation in response to elevated CO236,37,38,39, acting as primary energy

source for methanogenic communities5. In accordance with our findings, data from a long-term elevated CO2 experiment in the adjacent GCReW field site show a strong CO2 stimulation of CH4

emissions from pure stands of _Schoenoplectus_40. Furthermore, elevated CO2 increased both porewater concentrations of CH4 and dissolved organic C41, effects that could likewise be

attributed to greater inputs of organic matter via root exudation or rapid root turnover. Previous work conducted at larger plot scales and over multiple years in mixed communities of the

GCReW site has shown that elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization shift the balance between _Schoenoplectus_ and _Spartina_ in opposite directions (i.e. nitrogen favored _Spartina_ over

_Schoenoplectus_ and vice versa)42. Given the overriding control of plant community composition on CH4 emissions found in the present study, this implies that the longer-term effects of

these global change factors may differ from the effects presented here, which reflect relatively short-term effects over two growing seasons. However, the present work also demonstrates that

SLR represents an overriding global change driver in the studied system. We therefore argue that shifts in plant species dominance in response to elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization

observed under ambient rates of SLR42,43 may be less important under higher rates of SLR as simulated in the present study. This notion is supported by the observation that decadal‐scale

oscillations in local sea level at GCReW have stronger effects on plant community composition than elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization treatments of the long-term field experiments34,44.

PLANT TRAITS AFFECTING CH4 DYNAMICS In accordance with clear plant species effects on CH4 emissions, soil redox conditions in the pure communities of Experiment 2 were more strongly

affected by plant species than by sea level (Fig. 2d). Redox was markedly higher in _Schoenoplectus_ vs. _Spartina_ rhizospheres by c. 180 and 100 mV at +15 and +35 cm above MSL,

respectively (_F_ = 13.0; _p_ ≤ 0.01). Soil redox conditions reflect the balance between plant-mediated transport of electron donors and acceptors. Therefore, our findings demonstrate either

a greater provision of electron acceptors (i.e. oxygen) or a lower provision of electron donors (organic matter) in _Schoenoplectus_ vs. _Spartina_ rhizospheres. Importantly, both

mechanisms would cause lower CH4 production in _Schoenoplectus_ rhizospheres. Redox was significantly higher at +35 cm above MSL than at the lower and more frequently flooded +15 cm

treatment (_F_ = 10.2; _p_ ≤ 0.05), demonstrating the expected suppression of rising sea level on oxygen availability. Notably, there was no statistical difference (_p_ = 0.99) in soil redox

potential in the presence of _Schoenoplectus_ at the wettest treatment (+15 cm) and _Spartina_ at the driest (+35 cm) treatment (Fig. 2d). Consistent with our CH4 results, this demonstrates

a stronger plant vs. sea level control on soil redox conditions in the studied system and underpins the primary control of plant species composition, and to a lesser degree sea level per

se, on soil biogeochemistry. The redox data suggest that greater CH4 emissions in _Spartina_ vs. _Schoenoplectus_ are driven by plant traits affecting the balance between plant-mediated

transport of electron donors and acceptors into the soil. There is abundant evidence to support greater supply of oxygen to the rhizosphere by _Schoenoplectus_ vs. _Spartina_ via root oxygen

loss. Studies conducted on morphologically similar species of the same genus in tidal freshwater and nontidal wetland systems demonstrated markedly higher plant-stimulation of oxidation

than production of CH413,45,46,47. Root oxygen loss by wetland plants supports higher rates of CH4 oxidation and stimulates the decomposition of soil organic matter, a phenomenon called

priming48. Previous work at the study site demonstrated high rates of priming in _Schoenoplectus_ rhizospheres, whereas priming in _Spartina_ rhizospheres was absent or even negative49. This

finding provides further evidence of higher oxygen transport to soils by _Schoenoplectus_ than _Spartina_, and it suggests opposing effects of root oxygen loss on priming and CH4 emissions

in a greenhouse-gas context. Indeed, in a past study we also demonstrated that priming in _Schoenoplectus_ rhizospheres scales positively with aboveground biomass50, opposite the response of

CH4 emissions to aboveground biomass in the present study (Fig. 3a, d). The contrasting effects of the two species on CH4 emissions may also be caused by differences in electron donor

input, such as higher rates of root exudation in _Spartina_ vs. _Schoenoplectus_ rhizospheres. Recent studies in Chinese tidal wetlands demonstrated that invasive _Spartina alterniflora_

stimulated CH4 emissions through higher exudation of labile organic substrates from _S. alterniflora_ roots in comparison to native species15,51. We do not have data on root exudate quality

and quantity in _Spartina_- vs. _Schoenoplectus_-dominated mesocosms, but data from the adjacent reference marsh platform indeed show markedly higher porewater concentrations of dissolved

organic C in _Spartina_41,52. One alternative explanation for greater CH4 emissions from _Spartina_ vs. _Schoenoplectus_ is that _Spartina_ supports greater rates of plant transport of CH4

from the soil via the plant-aerenchyma system. This explanation, however, is implausible because _Spartina patens_ has a poorly developed aerenchyma system compared to _Schoenoplectus

americanus_53, and concentrations of porewater CH4 in the adjacent reference marsh are higher in _Spartina_ vs. _Schoenoplectus_ rhizospheres52. Taken together, it is likely that two

processes—higher root oxygen loss by _Schoenoplectus_ and higher root exudation by _Spartina_—explain the contrasting effects of these species on CH4 emissions in the present study and

thereby determined the dramatic change in CH4 emissions in response to sea level-induced species shifts. IMPLICATIONS Other than salinity, drivers of variability in CH4 emissions from tidal

wetlands are poorly understood, which represents one of the biggest challenges to building robust numerical forecast models of greenhouse-gas dynamics for blue C ecosystems16. CH4 emissions

from the ambient CO2 treatments of our main experiment ranged between 2.3 and 8.4 g CH4 m−2 year−1 (Fig. 1b) and thereby reflect the lower spectrum of reported values for mesohaline marshes

based on a recent global meta-analysis (−0.5 to 551.1 g CH4 m−2 year−1)7 and earlier work with focus on North America (3.3–32.0 g CH4 m−2 year−1)6. Relative sea level exerted a strong,

nonlinear control on CH4 emissions. The difference between lowest and highest mean CH4 emissions was 31 g CH4 m−2 year−1 (Fig. 2a), corresponding to c. 6% of the total range of CH4 emissions

reported for tidal marshes globally7 and to c. 95% of the total range reported for differences between meso- and polyhaline tidal marshes based on the salinity-CH4 model of Poffenbarger et

al.6. We furthermore show strong positive effects of elevated CO2 which increased CH4 emissions an amount similar to sea level effects. Our study thereby identifies two important drivers of

CH4 emissions both with a large potential to change the future greenhouse-gas balance of blue C ecosystems. The main value of the present work is based on the mechanisms it illustrates,

which are largely independent of absolute effect sizes. This is the first study to experimentally test if SLR interacts with other global change factors to change CH4 emissions from blue C

ecosystems. We demonstrate that predictions of both direction and magnitude of sea level effects on CH4 emissions require an understanding of plant species traits that have the capacity to

drive dramatic changes in redox chemistry. Furthermore, we show that effects of the global change factors elevated CO2 and nitrogen interact differently with sea level. Effects of nitrogen

fertilization were consistently null while the effects of elevated CO2 were consistently positive. Indeed, CO2 effects tended to amplify with more extreme sea levels. Our findings therefore

yield important implications for modeling current and future greenhouse-gas dynamics of blue C ecosystems. MATERIAL AND METHODS STUDY SITE The study was carried out in a tidal wetland site

on Rhode river, a sub-estuary of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, USA (38°53′N, 76°33′W). The field site is home to the GCReW site operated by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

Tidal amplitude at the site is <50 cm and salinity generally <15 ppt. Soils are peats with organic matter contents >80%. Site vegetation is dominated by the C3 sedge

_Schoenoplectus_ _americanus_ (hereafter _Schoenoplectus_) at lower, more frequently flooded elevations and by the C4 grass _Spartina_ _patens_ (hereafter _Spartina_) at higher, less

frequently flooded elevations. The two species occur in pure and mixed communities depending on surface elevation. Over the past two decades, a fast, SLR-driven encroachment of

_Schoenoplectus_ into _Spartina_ communities has been observed34. Plant growth at the site is nitrogen limited. Ammonium makes up >99% of the porewater inorganic nitrogen pool, and

nitrate concentrations are usually below detection limits42,54. The main tidal creek of the GCReW site accommodates a marsh organ facility. Marsh organs (_sensu_ Morris31) consist of

field-based mesocosms arranged at different elevations, and thus different relative sea levels, to manipulate flooding frequency and assess the effects of accelerated relative SLR on plant

and soil processes. Here we report on the results of two separate marsh organ experiments conducted between 2011 and 2012. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGNS The design of Experiment 1 has been described

by Langley et al.27 and was originally designed to study the effects of interacting global change factors on plant growth. It represents the first study to combine marsh organs and open top

chambers to manipulate relative sea level and atmospheric CO2 concentrations at the same time. An additional component of the study is an elevated nitrogen treatment. The three treatments

were applied in a full-factorial design. Mesocosms (70-cm deep, 10-cm diameter) were filled with peat soil, planted with mixed native species assemblages of _Spartina_ and _Schoenoplectus_,

and evenly distributed on six separate marsh organs (_n_ = 24 per marsh organ). Initial planting reflected natural stem densities of the two species in the adjacent high mash27. Within each

marsh organ, mesocosms were installed at the following six elevations in relation to MSL of the growing season (May–Sep): MSL −25 cm, MSL −15 cm, MSL −5 cm, MSL +5 cm, MSL +20 cm, and MSL

+40 cm. Treatments covered the current relative sea level range of the adjacent marsh (three highest elevations) as well as future sea level scenarios (three lowest elevations)27,54.

Long-term average SLR (90-year trend) at the site is c. 4 mm year−1. MSL was calculated based on tide gauge data (Annapolis, MD, Station ID: 8575512, URL: https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov)

after each growing season and could therefore only be estimated before mesocosm deployment. The fraction of time flooded ranged from 3% to 96% across the six elevations27. The elevated CO2

treatment was applied by placing a floating open top chamber over each of the six marsh organs that was capable of rising and falling with the tide cycle. Three of the marsh organs were

exposed to elevated CO2 (ambient [CO2] + 300 ppm, simulating an atmospheric CO2 scenario projected for the year 210055) by receiving additional CO2 mixed into the air stream of a blower

system connected to each open top chamber. The other three marsh organs were equipped with identical open top chambers and air blower systems but did not receive additional CO2 via the air

stream. Half of the mesocosms were exposed to an elevated nitrogen treatment projected to increase soil mineral nitrogen concentrations by c. 40%. Ammonium chloride solution equivalent to an

nitrogen input of 25 g N m−2 was injected to the rhizosphere on a biweekly basis throughout the growing season. A follow-up marsh organ experiment, Experiment 2, was conducted to separate

effects of plant species identity (i.e. _Schoenoplectus_ vs. _Spartina_) from effects of interspecific plant competition on CH4 emissions. This experiment used monocultures of either

_Schoenoplectus_ or _Spartina_, and no CO2 or nitrogen treatments were applied. Mesocosms were exposed to three sea level treatments: MSL ±0 cm, MSL +15 cm, and MSL +35 cm. For details we

refer the reader to Mueller et al.50. Mesocosm artifacts need to be considered when interpreting the absolute rates of CH4 emissions and effect sizes reported here. For instance, marsh organ

experiments at GCReW, including the present experiments, generally produce more biomass per area than the adjacent field site27,34,43,49. We therefore assessed the extent to which absolute

CH4 emissions and CH4 emissions as a function of species composition (i.e. the key finding of our mesocosm experiments) differ between mesocosms and field plots of the adjacent marsh. Mean

growing season CH4 emissions were quantified in the _Salt Marsh Accretion Response to Temperature eXperiment_ (SMARTX) operating in a high elevation, _Spartina_-dominated area and a low

elevation, _Schoenoplectus_-dominated area of the adjacent marsh. A detailed description of the SMARTX study design is given by Noyce et al.56. Here we do not analyze temperature effects on

CH4 emissions, but compare CH4 emissions from the ambient plots of the two plant communities (_n_ = 3) and assess the relationship between the relative abundance of the two plant species and

CH4 emissions across all treatments (_n_ = 24). MEASUREMENTS CH4 emission measurements followed the flux measurement protocol for marsh organs presented in Mueller et al.50 with slight

modifications for CH4. In July 2011, in the second consecutive growing season of Experiment 1, mesocosms were carefully moved from the marsh organs into 120-L containers positioned directly

adjacent. Due to poor plant survival at the lowest elevations, CH4 emission measurements were restricted to elevations of MSL −5 cm and higher. Containers were filled with creek water to the

depth that corresponded to the water level that mesocosms were last exposed to in the marsh organ. Clear, acrylic flux chambers (volume = 7.5 L) were placed onto each mesocosm and sealed.

Gas samples (20 mL) were collected from the chamber headspace every 20 min for a period of 2 h and analyzed for CH4 using a gas chromatograph (Varian 450, Agilent Technologies). CH4 fluxes

were calculated from linear regression slopes (chamber headspace [CH4] vs. time) following the ideal gas law, using chamber temperature for each given time point and assuming ambient

pressure. Only fluxes with _R_2 ≥ 0.8 were used (mean _R_2 = 0.95 ± 0.05 SD, _N_ = 82). The detection limit was 9 µmol CH4 m−2 h−1. CH4 emission measurements of Experiment 2 were conducted

in Sep 2012, after c. 4 months of plant growth in the marsh organ in the first growing season of the experiment. Sampling procedures followed Experiment 1, with the exception that samples

were analyzed using a Shimadzu GC-14A (Shimadzu Corporation). Only fluxes with _R_2 ≥ 0.8 were used (mean _R_2 = 0.96 ± 0.05 SD, _N_ = 16). The detection limit was 2 µmol CH4 m−2 h−1.

_Spartina_ did not survive at MSL ±0 cm in Experiment 2. This elevation was therefore not considered for comparisons between species. Field CH4 emission measurements in SMARTX were conducted

monthly from Jun 12 to Sep 4, 2019, 3 years after flux chamber bases were installed. Chambers (40 × 40 × 40 cm) were stacked onto each chamber base (total volume = 64–256 L) and covered

with an opaque shroud. An ultra-portable greenhouse-gas analyzer (Los Gatos Research) was used to measure headspace CH4 concentrations every 3 s for 5 min. Fluxes were calculated as

described above and only fluxes that were significant at _p_ ≤ 0.05 were included in the analysis. Detection limit was <0.6 µmol CH4 m−2 h−1. In order to gain more mechanistic insight

into potential effects of plant species shifts on CH4 dynamics, soil redox conditions were measured in Experiment 2. Redox measurements were conducted during a single campaign in Sep 2012,

after c. 4 months of plant growth in the marsh organ. Measurements were taken on _n_ = 3 mesocosms per plant species and elevation at low tide. Three platinum-tipped redox electrodes57 were

inserted to a soil depth of 10 cm and allowed to equilibrate for 45 min. For readings, a calomel reference electrode (Fisher Scientific accumet) was inserted to a soil depth of 1 cm, and

reference and redox electrodes were connected to a portable conductivity meter (Fisher Scientific accumet). Readings were corrected to the redox potential of the standard hydrogen electrode

(+244 mV). STATISTICAL ANALYSES Analyses for Experiment 1 followed Langley et al.27. Three-way split-plot ANOVA was used to test for the effects of elevation (relative sea level), CO2,

nitrogen, and their factorial interactions on CH4 emissions. Marsh organ (1–6) was included as a random factor in the model. Within single marsh organs, mesocosms of the same treatment

combination were considered technical duplicates, and the mean of each duplicate was considered the experimental unit. Replication was therefore _n_ = 3 per treatment. Subsequent two-way

ANOVAs were used to assess CO2 and nitrogen effects within each elevation treatment. Linear and nonlinear regression analysis was used to further explore the relationship of elevation and

CH4 emissions. In order to identify possible relationships between plant biomass parameters and CH4 emissions, we used biomass data obtained from a destructive harvest in Sep 2011 (c. two

months after the CH4 emission measurements) that has been presented in Langley et al.27. Specifically, we conducted linear regression to test whether biomass parameters (Supplementary Table

2) and CH4 emissions are related both across and within various treatment combinations. Two-way ANOVA was used to test for effects of plant species and elevation on CH4 emissions and soil

redox in Experiment 2. Tukey’s HSD tests were used for pairwise comparisons following ANOVAs where appropriate. One-way ANOVA and linear regression were used to analyze the field CH4

emission data (Fig. 4). CH4 emission data typically show a log-normal distribution40,58. Data were log-transformed to improve normality (if required based on visual assessments) or when

Levene’s test indicated heterogenous variance. Regression analyses were conducted with both log-transformed and untransformed data. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.2 (R

Foundation for Statistical Computing) and PAST version 3.20.59. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this

article. DATA ACCESSIBILITY Data used in this work are available from the corresponding authors upon request and at the Smithsonian Institution figshare repository

(https://smithsonian.figshare.com) under the https://doi.org/10.25573/serc.12855323. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 22 MARCH 2023 A Correction to this paper has been published:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37364-5 _ REFERENCES * Bridgham, S. D., Megonigal, J. P., Keller, J. K., Bliss, N. B. & Trettin, C. The carbon balance of North American wetlands.

_Wetlands_ 26, 889–916 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Windham-Myers, L. et al. Tidal wetlands and estuaries. in _Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report_ (eds Cavallaro, N. et al.)

596–648 (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018) * Poulter, B. et al. Global wetland contribution to 2000–2012 atmospheric methane growth rate dynamics. _Environ. Res. Lett._ 12,

https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8391 (2017). * Saunois, M. et al. The global methane budget 2000–2017. _Earth Syst. Sci._ 12, 1561–1623 (2020). Article ADS Google Scholar * Megonigal,

J. P., Hines, M. E. & Visscher, P. T. Anaerobic metabolism: linkages to trace gases and aerobic processes. in _Biogeochemistry_ (ed. Schlesinger, W. H.) 317–424 (Elsevier-Pergamon,

2004). * Poffenbarger, H. J., Needelman, B. A. & Megonigal, J. P. Salinity influence on methane emissions from tidal marshes. _Wetlands_ 31, 831–842 (2011). Article Google Scholar *

Al-Haj, A. N. & Fulweiler, R. W. A synthesis of methane emissions from shallow vegetated coastal ecosystems. _Glob. Change Biol_ 26, 2988–3005 (2020). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Oreska, M. P. J. et al. The greenhouse gas offset potential from seagrass restoration. _Sci. Rep_. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64094-1 (2020). * Rosentreter, J. A., Maher, D. T.,

Erler, D. V., Murray, R. H. & Eyre, B. D. Methane emissions partially offset “blue carbon” burial in mangroves. _Sci. Adv._ https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao4985 (2018). * Crooks, S. et

al. Coastal wetland management as a contribution to the US National Greenhouse Gas Inventory. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 8, 1109–1112 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Chamberlain, S. D. et al. Soil properties and sediment accretion modulate methane fluxes from restored wetlands. Glob. _Chang. Biol._ 24, 4107–4121 (2018). Article Google Scholar

* Call, M. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of carbon dioxide and methane fluxes over semi-diurnal and spring-neap-spring timescales in a mangrove creek. _Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta_

150, 211–225 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * van der Nat, F.-J. W. A. & Middelburg, J. J. Effects of two common macrophytes on methane dynamics in freshwater sediments.

_Biogeochemistry_ 43, 79–104 (1998). Article Google Scholar * Mueller, P. et al. Complex invader-ecosystem interactions and seasonality mediate the impact of non-native _Phragmites_ on CH4

emissions. _Biol. Invasions_ 18, 2635–2647 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Tong, C., Morris, J. T., Huang, J., Xu, H. & Wan, S. Changes in pore-water chemistry and methane emission

following the invasion of _Spartina alterniflora_ into an oliogohaline marsh. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 63, 384–396 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Macreadie, P. I. et al. The future

of Blue Carbon science. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 3998 (2019). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Spivak, A. C., Sanderman, J., Bowen, J. L., Canuel, E. A. & Hopkinson, C.

S. Global-change controls on soil-carbon accumulation and loss in coastal vegetated ecosystems. _Nat. Geosci._ 12, 685–692 (2019). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kirwan, M. L. &

Megonigal, J. P. Tidal wetland stability in the face of human impacts and sea-level rise. _Nature_ 504, 53–60 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Duarte, C. M., Losada, I.

J., Hendriks, I. E., Mazarrasa, I. & Marba, N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 3, 961–968 (2013). Article ADS

CAS Google Scholar * Rogers, K. et al. Wetland carbon storage controlled by millennial-scale variation in relative sea-level rise. _Nature_ 567, 91–95 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Megonigal, J. P. & Schlesinger, W. H. Enhanced CH4 emissions from a wetland soil exposed to elevated CO2. _Biogeochemistry_ 37, 77–88 (1997). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Beaulieu, J. J., DelSontro, T. & Downing, J. A. Eutrophication will increase methane emissions from lakes and impoundments during the 21st century. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 1375

(2019). Article Google Scholar * Wilson, R. M. et al. Stability of peatland carbon to rising temperatures. _Nat. Commun._ 7, 13723 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Stocker, B. D. et al. Multiple greenhouse-gas feedbacks from the land biosphere under future climate change scenarios. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 3, 666–672 (2013). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Knoblauch, C., Beer, C., Liebner, S., Grigoriev, M. N. & Pfeiffer, E. M. Methane production as key to the greenhouse gas budget of thawing permafrost. _Nat. Clim.

Chang._ 8, 309–312 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Whiting, G. J. & Chanton, J. P. Primary production control of methane emission from wetlands. _Nature_ 364, 794–795

(1993). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Langley, J. A., Mozdzer, T. J., Shepard, K. A., Hagerty, S. B. & Megonigal, J. P. Tidal marsh plant responses to elevated CO2, nitrogen

fertilization, and sea level rise. Glob. _Chang. Biol._ 19, 1495–1503 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Mueller, P. et al. Global-change effects on early-stage decomposition processes in

tidal wetlands—implications from a global survey using standardized litter. _Biogeosciences_ 15, 3189–3202 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kirwan, M. L. & Guntenspergen, G.

R. Feedbacks between inundation, root production, and shoot growth in a rapidly submerging brackish marsh. _J. Ecol._ 100, 764–770 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Redelstein, R., Dinter,

T., Hertel, D. & Leuschner, C. Effects of inundation, nutrient availability and plant species diversity on fine root mass and morphology across a saltmarsh flooding gradient. _Front.

Plant Sci._ 9, 1–15 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Morris, J. T. Estimating net primary production of salt marsh macrophytes. in _Principles and Standards for Measuring Primary

Production_ (eds Fahey, T. J. & Knapp, A. K.) 106–119 (Oxford University Press, 2007). * Arp, W. J., Drake, B. G., Pockman, W. T., Curtis, P. S. & Whigham, D. F. Interactions between

C3 and C4 salt marsh plant species during four years of exposure to elevated atmospheric CO2. _Vegetatio_. 104, 133–143 (1993). Article Google Scholar * Erickson, J. E., Megonigal, J. P.,

Peresta, G. & Drake, B. G. Salinity and sea level mediate elevated CO2 effects on C3-C4 plant interactions and tissue nitrogen in a Chesapeake Bay tidal wetland. _Glob. Chang. Biol._

13, 202–215 (2007). Article ADS Google Scholar * Drake, B. G. Rising sea level, temperature, and precipitation impact plant and ecosystem responses to elevated CO2 on a Chesapeake Bay

wetland: Review of a 28-year study. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 20, 3329–3343 (2014). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Kirwan, M. L., Langley, J. A., Guntenspergen, G. R. & Megonigal, J.

P. The impact of sea-level rise on organic matter decay rates in Chesapeake Bay brackish tidal marshes. _Biogeosciences_ 10, 1869–1876 (2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Phillips,

R. P., Finzi, A. C. & Bernhardt, E. S. Enhanced root exudation induces microbial feedbacks to N cycling in a pine forest under long-term CO2 fumigation. _Ecol. Lett._ 14, 187–194

(2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Phillips, R. P., Bernhardt, E. S. & Schlesinger, W. H. Elevated CO2 increases root exudation from loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) seedlings as an

N-mediated response. _Tree Physiol._ 29, 1513–1523 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lin, G., Ehleringer, J. R., Rygiewicz, P. T., Johnson, M. G. & Tingey, D. T. Elevated

CO2 and temperature impacts on different components of soil CO2 efflux in Douglas-fir terracosms. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 5, 157–168 (1999). Article ADS Google Scholar * Megonigal, J. P. et

al. A plant-soil-atmosphere microcosm for tracing radiocarbon from photosynthesis through methanogenesis. _Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J._ 63, 665–671 (1999). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Dacey, J. W. H., Drake, B. G. & Klug, M. J. Stimulation of methane emission by carbon dioxide enrichment of marsh vegetation. _Nature_ 370, 47–49 (1994). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Keller, J. K., Wolf, A. A., Weisenhorn, P. B., Drake, B. G. & Megonigal, J. P. Elevated CO2 affects porewater chemistry in a brackish marsh. _Biogeochemistry_ 96, 101–117

(2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Langley, J. A. & Megonigal, J. P. Ecosystem response to elevated CO2 levels limited by nitrogen-induced plant species shift. _Nature_ 466, 96–99

(2010). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Langley, J. A., McKee, K. L., Cahoon, D. R., Cherry, J. A. & Megonigal, J. P. Elevated CO2 stimulates marsh elevation gain,

counterbalancing sea-level rise. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A._ 106, 6182–6186 (2009). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Langley, J. A. et al. Ambient changes

exceed treatment effects on plant species abundance in global change experiments. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 24, 5668–5679 (2018). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Bhullar, G. S., Edwards,

P. J. & Olde Venterink, H. Variation in the plant-mediated methane transport and its importance for methane emission from intact wetland peat mesocosms. _J. Plant Ecol._ 6, 298–304

(2013). Article Google Scholar * van der Nat, F.-J. W. A., Middelburg, J. J., Van Meteren, D. & Wielemakers, A. Diel methane emission patterns from _Scirpus lacustris_ and _Phragmites

australis_. _Biogeochemistry_ 41, 1–22 (1998). Article Google Scholar * Van Der Nat, F. J. W. A. & Middelburg, J. J. Seasonal variation in methane oxidation by the rhizosphere of

_Phragmites australis_ and _Scirpus lacustris_. _Aquat. Bot._ 61, 95–110 (1998). Article Google Scholar * Wolf, A. A., Drake, B. G., Erickson, J. E. & Megonigal, J. P. An

oxygen-mediated positive feedback between elevated carbon dioxide and soil organic matter decomposition in a simulated anaerobic wetland. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 13, 2036–2044 (2007). Article

ADS Google Scholar * Bernal, B., Megonigal, J. P. & Mozdzer, T. J. An invasive wetland grass primes deep soil carbon pools. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 23, 2104–2116 (2017). Article ADS

PubMed Google Scholar * Mueller, P., Jensen, K. & Megonigal, J. P. Plants mediate soil organic matter decomposition in response to sea level rise. _Glob. Chang. Biol._ 22, 404–414

(2016). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Yuan, J. et al. _Spartina alterniflora_ invasion drastically increases methane production potential by shifting methanogenesis from

hydrogenotrophic to methylotrophic pathway in a coastal marsh. _J. Ecol._ 107, 2436–2450 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Marsh, A. S., Rasse, D. P., Drake, B. G. & Megonigal, J.

P. Effect of elevated CO2 on carbon pools and fluxes in a brackish marsh. _Estuaries_ 28, 694–704 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Broome, S. W., Mendelssohn, I. A. & McKee, K. L.

Relative growth of _Spartina patens_ (Ait.) Muhl. and _Scirpus olneyi_ gray occurring in a mixed stand as affected by salinity and flooding depth. _Wetlands_ 15, 20–30 (1995). Article

Google Scholar * Mozdzer, T. J., Langley, J. A., Mueller, P. & Megonigal, J. P. Deep rooting and global change facilitate spread of invasive grass. _Biol. Invasions_ 18, 2619–2631

(2016). Article Google Scholar * IPCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. _United Nations Framew._ _Conv. Clim. Chang._

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9388.1992.tb00046.x (2014). * Noyce, G. L., Kirwan, M. L., Rich, R. L. & Megonigal, J. P. Asynchronous nitrogen supply and demand produce nonlinear plant

allocation responses to warming and elevated CO2. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A._ 116, 21623–21628 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Megonigal, J. P. &

Rabenhorst, M. Reduction–oxidation potential and oxygen. in _Methods in Biogeochemistry of Wetlands_ (eds DeLaune, R. D., Reddy, K. R., Richardson, C. J. & Megonigal, J. P.) 71–85 (Soil

Science Society of America, Inc., 2013). * Aselmann, I. & Crutzen, P. J. Global distribution of natural freshwater wetlands and rice paddies, their net primary productivity, seasonality

and possible methane emissions. _J. Atmos. Chem._ 8, 307–358 (1989). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. Past: paleontological statistics software

package for education and data analysis. _Palaeontol. Electron._ 4, 4 (2001). Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by Maryland Sea Grant (SA7528082,

SA7528114-WW), the National Science Foundation Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology Program (DEB-0950080, DEB-1457100, and DEB-1557009), the US Department of Energy, Office of

Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research Program (DE-SC0014413 and DE-SC0019110), the Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) Program (851303), and the Smithsonian

Institution. Peter Mueller was supported by the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) PRIME fellowship program funded through the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

This study is a contribution to the Cluster of Excellence ‘CLICCS—Climate, Climatic Change, and Society’ and to the Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN) of Universität

Hamburg. FUNDING Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Edgewater, MD, 21037, USA

Peter Mueller, Genevieve L. Noyce & J. Patrick Megonigal * Institute of Soil Science, Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN), Universität Hamburg, 20146, Hamburg,

Germany Peter Mueller * Department of Biology, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, 19010, USA Thomas J. Mozdzer * Department of Biology, Center for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Stewardship,

Villanova University, Villanova, PA, 19003, USA J. Adam Langley * Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA Lillian R. Aoki Authors * Peter

Mueller View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thomas J. Mozdzer View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * J. Adam Langley View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lillian R. Aoki View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Genevieve L. Noyce View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J. Patrick Megonigal View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS P.M. analyzed the data and wrote the initial manuscript. P.M. and L.R.A. conducted the marsh organ studies. G.L.N. conducted the

field study and analyzed the data. J.P.M., T.J.M., and J.A.L. conceived the marsh organ studies. J.P.M. and G.L.N. conceived the field study. All authors contributed to manuscript editing.

CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Peter Mueller or J. Patrick Megonigal. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER

REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Sparkle Malone and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Mueller, P., Mozdzer, T.J., Langley, J.A. _et al._ Plant species determine tidal wetland methane response to sea level rise. _Nat Commun_ 11, 5154 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18763-4 Download citation * Received: 27 April 2020 * Accepted: 01 September 2020 * Published: 14 October 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18763-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative