Hydrolase–like catalysis and structural resolution of natural products by a metal–organic framework

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The exact chemical structure of non–crystallising natural products is still one of the main challenges in Natural Sciences. Despite tremendous advances in total synthesis, the

absolute structural determination of a myriad of natural products with very sensitive chemical functionalities remains undone. Here, we show that a metal–organic framework (MOF) with

alcohol–containing arms and adsorbed water, enables selective hydrolysis of glycosyl bonds, supramolecular order with the so–formed chiral fragments and absolute determination of the organic

structure by single–crystal X–ray crystallography in a single operation. This combined strategy based on a biomimetic, cheap, robust and multigram available solid catalyst opens the door to

determine the absolute configuration of ketal compounds regardless degradation sensitiveness, and also to design extremely–mild metal–free solid–catalysed processes without formal acid

protons. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SOLUBLE INDIVIDUAL METAL ATOMS AND ULTRASMALL CLUSTERS CATALYZE KEY SYNTHETIC STEPS OF A NATURAL PRODUCT SYNTHESIS Article Open access 04

April 2024 INVERSE HYDRIDE SHUTTLE CATALYSIS ENABLES THE STEREOSELECTIVE ONE-STEP SYNTHESIS OF COMPLEX FRAMEWORKS Article Open access 20 October 2022 PROGRAMMABLE LATE-STAGE C−H BOND

FUNCTIONALIZATION ENABLED BY INTEGRATION OF ENZYMES WITH CHEMOCATALYSIS Article 29 April 2021 INTRODUCTION The absolute structural configuration of natural products has been historically

verified by total synthesis1, either from commercial compounds or, more conveniently, from fragments of the compound after controlled degradation and re-synthesis. However, the later

approach is often hampered by the sensitiveness of natural complex molecules. For instance, the glycosyl bond1 (–O–CR2–O–) is prevalent in natural products since glycosidase (hydrolase)

enzymes are widespread in all domains of life to generate (and break) ketals with an extremely high selectivity, at neutral pH in water, by the combined action of some amino acid residues in

the confined enzyme electrostatic pocket. However, classical synthetic chemistry operates under much harder conditions, by using formal acids (i.e., protons and Lewis metal cations) or

bases (i.e., inorganic bases and amines), which are clearly incompatible with the outstanding structural richness and sensitive functionality of ketals in Nature, and severely hampers the

absolute determination of natural product structures by simple chemical degradation2,3. Microporous solids may mimic enzymes with their active catalytic species in an electrostatic confined

space4,5. Indeed, simple microporous aluminosilicates are good catalysts for ketal deprotection6, but they show low selectivity towards other acid sensitive functional groups, since the

catalytic activity comes from acid protons associated with the solid network7. Early observations in microporous pure silicates showed that densely packed and interacting Si–OH groups,

called silanol nests, naturally generate an acid site for catalysis without the participation of a formal proton8,9, however, the concept could not be extended to the organic functionalities

present in enzymes, such as alcohols, since alcohols tend to generate either alkoxides4 or carbocationic species10 rather than acid sites, unless water11 or acetic acid12 are co-added.

These precedents severely preclude simple alumisolicates to be used as catalase-like catalysts13 with extremely mild, bifunctional acid/base sites. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)14 are

porous crystalline materials amenable to single-crystal X-ray crystallography15 (SCXRD), with a great synthetic control of their high-dimensional architectures and concomitant porosity by a

fine tuning of the functionalities decorating their channels using both pre- or post-synthetic16,17 methods. Indeed, their thrilling host–guest chemistry has led to the selective

incorporation of gases, solvents, small molecules or more complex molecular systems18,19. Besides, advances like the crystalline sponge method20, developed by Fujita’s group, allows the

absolute determination of organic molecules within the MOF framework21,22,23. Thus, seems plausible to go one-step further for the development of novel families of MOFs, specifically

designed to combine the catalytic in-situ formation1,24,25,26,27,28, capture29,30,31, organization19,32 and retention of very sensitive unknown organic species within their functional

channels33. Herein, we report that a previously reported30,31,34 highly robust crystalline MOF-derived from the natural amino acid _l_-serine and whose micropores are densely decorated with

methyl alcohol groups is capable to accommodate relatively big natural products, and performs, in a single operation, ketal deprotection and structural determination of sugars1 and

flavonoids of known and unknown absolute configuration. After selectively incorporating, untouched, the fragment of unknown chirality into the MOF, the solid structure is resolved by SCXRD

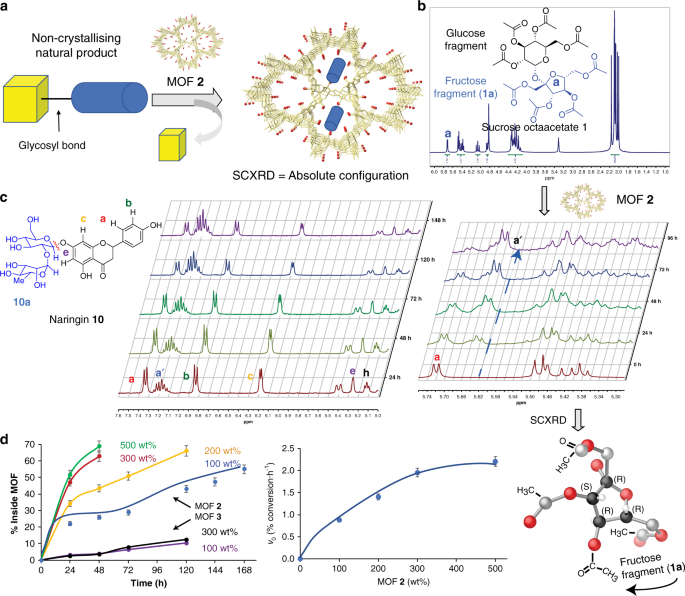

to give the absolute configuration of the adsorbed organic fragment (Fig. 1a) and, thus, of the natural product. RESULTS GLYCOLYSIS OF NATURAL PRODUCTS OF KNOWN STRUCTURE Figure 1b shows the

proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1H NMR) of a solution of sucrose octaacetate 1 (neat sucrose was not soluble under reaction conditions) recorded with time in the presence of the

amino acid-based catalytic MOF 2, which features hexagonal pores densely decorated with –OH groups, and with formula {CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-serimox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 39H2O (2) (where serimox30,31,34

= bis[(_S_)-serine]oxalyl diamide, see also Supplementary Fig. 1). Isostructural MOF alamox (3) of formula {CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-alamox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 32H2O (where alamox =

bis[(_S_)-alanine]oxalyl diamide) without alcohol but only methyl pending groups was used for comparison. The results show that the NMR signal corresponding to the ketal linkage (a) and, in

general, all the signals associated with one of the parts of ketal 1, the fructose fragment 1A, progressively disappears in solution in the presence of MOF 2, while the glucose fragment 1B

remains. Conversely, no hydrolysis was observed with MOF 3, lacking confined alcohol groups. Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses confirmed the nearly exclusive

presence of glucose fragments 1B in solution after treatment with MOF 2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). SCXRD of a crystalline sample of MOF 2 reacted with 1 (see “Methods” and Supplementary

Methods) rendered a new host–guest material with formula (1A)@{CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-serimox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 19H2O (1A@2) (where 1A = 1,3,4,6-Tetra-_O_-acetylfructofuranoside), whose crystal

structure as well as absolute configuration could be elucidated by SCXRD analysis (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1 and also an in-depth analysis of 1A@2 crystal structure in

Supplementary Methods). The results show that the only fragment found inside MOF 2 is fructose 1A and not any glucose derivative (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 3–6 and Fig. 2 and

crystallographic section in SI for details). These fragments, well defined by furanose ring, that is completely assigned by electron density maps, reside in the pores of MOF 2 anchored by

means of strong hydrogen bonds involving locked water molecules, which act as a bridge between serine moieties and fructose molecules. So, the alcohol groups show a prominent role, providing

the suitable polar environment to host fructose molecules, effectively retained and organized within the pores. In order to better visualize and also to determine the relative catalytic

hydrolysis rate compared to alcohol dihydroxylation (a representative competitive reaction in natural product degradation), the benzaldehyde and cyclohexanone ketals 4 and 5, and

2-phenyl-2-propanol 6, were employed as substrates for ketal hydrolysis and the dehydroxylation reaction, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7). The kinetic results showed the formation of

carbonyl compounds 7 and 8 at a significant rate for MOF 2 (5 mol% of MOF structural units respect to the substrate), but not for MOF 3. Remarkably, despite the formation of alkene 9 may be

expected to be extremely easy with a highly stable benzylic carbocation intermediate, the hydrolysis rate is twice for the dehydroxylation of 6. These results confirm that MOF 2 selectively

catalyzes the hydrolysis of glycosyl bonds without significant degradation of alcohol-substituted chiral carbons. To further validate the extremely mild solid-catalyzed glycosyl

bond-breaking reaction, the commercially available flavonoid naringin 10 (Supplementary Fig. 8), with a more complex glycosyl structure, was treated with catalytic amounts of MOFs 2 and 3.

Figure 1c shows the progressive disappearance of the 1H NMR signals corresponding to the alkyl fragment 10A respect to the aromatic part, the latter evolving to a different product in

solution which, according to NMR and GC-MS, may be assigned to the oxidized quinone derivative. The spontaneous oxidation of the aromatic part in flavonoids, after losing the stabilizing

glycosyl fragment, was expected according to the literature10,35. Figure 1d shows the increase in the hydrolysis rate of naringin 10 with MOF 2, but not with MOF 3, the latter in the same

range that the hydrolysis rate without catalyst. All the results above, together, strongly support that MOF 2 selectively breaks glycosyl bonds in natural products and, concomitantly,

adsorbs the so-formed alkyl chains, such as 1A in sucrose and 10A in naringin. GLYCOLYSIS AND STRUCTURAL RESOLUTION OF BRUTIERIDIN 11 Aiming to further test our hypothesis, we studied a

unique class of flavonoids that is found in bergamot fruit (Citrus Bergamia Risso et Poiteau) which, in addition to other citrus species such as naringin 10, neohesperidin and neoeriocitrin,

contains a relevant concentration of the anti-cholesterol agent 6-_O-_hydroxymethylglutaryl (HMG) ester derivative brutieridin 11 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10)36,37,38,39.

Flavonoids are secondary metabolites widespread in Nature and involved in different metabolic processes, offering potential clinical alternatives to current treatments. However, so far, the

challenging characterization of this kind of flavonoids has been carried out by the combination of High-performance liquid chromatography, MS, and NMR techniques, which have severe

shortcomings for the proper identification of their chiral centers. For instance, brutieridin 11 has been isolated and identified with the formula hesperetin

7-(2′′-R-rhamnosyl-6′′-(3′′′′-hydroxy-3′′′′-methylglutaryl)-glucoside36, but all attempts to crystallize it, thus determining its crystal structure and unveiling its chiral nature, have been

unsuccessful so far. Brutieridin 11 presents two glycosidic bonds and, beyond other sensitive functionalities, several secondary and tertiary chiral alcohols along its chemical structure.

It is noteworthy the presence of an alcohol group flanked by two different carboxylic groups in beta position (fragment 11A, Fig. 3a), an extremely sensitive chemical aggrupation prone to

suffer degradation under both acid or basic conditions, since the tertiary alcohol dehydrates under acid conditions to generate a stable alkene conjugated to any of both carboxylic groups

or, conversely, the alpha carbon to the carboxylic groups deprotonates under basic conditions to generate the same degraded products. These easy acid or base-triggered reactions, together

with the interferences and potential side reactions caused by the phenol, ester, ketone and ether groups also present in brutieridin 11, makes extremely difficult the selective degradation

of this natural product by any classical deketalization method. With the above data in mind, the hydrolysis of brutieridin 11 was attempted with MOF 2. A combined 1H NMR, ultraviolet–visible

spectrophotometry (UV–Vis), diffuse-reflectance UV–Vis spectrophotometry (DR–UV–Vis) and Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) study was performed in order to follow

concomitantly the fate of 11 in solution and within MOF 2. 1H NMR results (Supplementary Fig. 11) show that the hydrolysis indeed occurs. The alkyl fragment 11A progressively disappears from

the solution, and the aromatic fragment transforms into a more symmetric aromatic molecule that persists in solution. This new aromatic molecule is the quinone fragment, according to UV–Vis

and FT-IR (Supplementary Fig. 12) and also to GC-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13), akin to what occurred during the hydrolysis of naringin 10. DR–UV–Vis (Supplementary Fig. 14) and FT-IR

measurements (Supplementary Fig. 15) of the solid MOF 2 after reaction reveal that the aromatic fragment does not incorporate into the pores, in line with the results observed for naringin

10. To further confirm that the alkyl fragment 11A and not the aromatic part accommodates inside the MOF pores, 13C isotopically labeled brutieridin (11–_13__C_) was prepared and hydrolyzed

with MOF 2 (Supplementary Fig. 16). Figure 3b shows that only the methoxy signal (a) assignable to the methyl ester of 11A appears in the magic angle spinning (MAS) solid 13C NMR spectrum of

MOF 2 after hydrolysis of 11–_13__C_. The two anisolic signals (b and c) of the aromatic fragment, present in the 13C NMR spectrum of 11–_13__C_, are not present. These results strongly

support the selective incorporation of the chiral alkyl fragment 11A to the crystalline MOF structure, yielding the novel hybrid material (11A)@{CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-serimox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 15H2O

(11A@2), whose crystal structure as well as absolute configuration could now be elucidated by SCXRD analysis. Figure 4 shows the structure of 11A@2, determined by SCXRD, which confirms the

preservation of the networks of 2 after guests’ capture. It is isomorphic to 2 crystallizing in the _P_63 chiral space group of the hexagonal system and consists of a chiral honeycomb-like

three-dimensional (3D) calcium(II)–copper(II) network, featuring functional hexagonal channels of ca. 0.9 nm as virtual diameter. The flexible hydroxyl (–OH) groups of the serine amino acid

remain confined and stabilized by lattice water molecules, in the highly hydrophilic pores of the MOF (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 17–19). In these solvated nanospace, SCXRD underpinned

11A molecules disclosing their configurations and locations, despite the persistent disorder. The uni-nodal ACS six-connected net is built up from trans oxamidato-bridged dicopper(II) units,

{CuII2[(S,S)-serimox]} (Fig. 4), which act as linkers between the CaII ions through the carboxylate groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Neighboring Cu2+ and Cu2+/Ca2+ ions are further

interconnected by aqua/hydroxo groups (in a 1:2 statistical distribution) linked in a μ3 fashion (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Guest molecules of 11A reside in the pores, packed via hydrogen

bonds interactions, mediated by serine derivative arms (Fig. 4b–d and Supplementary Figs. 17–19). Moreover, intermolecular interactions of the chiral net of MOF 2 enabled that the chiral

carbon of the HMG side chain of 11A unveiled the _R_ absolute configuration (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 20), with its bounded hydroxyl group directly interacting with methyl alcohol arm

of the MOF (O5′···O1Hser = 3.014(10) Å). The detailed structures showed 11A arrangements (with a 1:3 statistical distribution, see Supplementary Methods for details and Supplementary Fig.

21), driven by the nature and size of the guest. In-depth analysis of the crystal structure reveals chiral 11A molecules packed via a plethora of strong H-bonds, as expected for a polar

molecule (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19), involving hydroxyl serine derivative arms directly linked to hydroxyl groups attached to both sugar moiety or HMG side chain [O···O

distances varying in the range 2.73(1)–3.01(1) Å] (Supplementary Fig. 19). Oxamate oxygen atoms from the coordination network assist with strong hydrogen bonds involving carboxyl of HMG

[Ooxamate···Ocarboxyl distances of 2.69(1) Å]. The vastly solvated nano-confined space further supports the host–guest recognition process, mediating the interaction with the net by lattice

water molecules acting as bridge between host and guests to reach the serine derivative arms [shortest O11A···OW and related Ow···Oser distances of 2.94(1) and 2.68(1) Å, respectively], also

involving the innate flexible carboxyl terminus of HMG side chain. This is reminiscent of the interaction mechanisms found in glycosidases enzymes40. Figure 3c shows that the controlled

hydrolysis of brutieridin 11 with sodium methoxide gives the fragment derivative _R_-12 by chiral-phase GC analysis, together with significant amounts of the epimerized fragment and some

other degraded fragments of the natural product, as determined with an independently synthesized, enantiomerically enriched sample of 12 obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis of diester 13

with pig liver estearase. Thus, one can say that the _R_ configuration is thus obtained within MOF 2 and also by conventional hydrolysis. This result strongly supports the validity of the

crystallization method to give the correct absolute configuration of unknown products by SCXRD. MECHANISM OF THE MOF-CATALYZED GLYCOSYL HYDROLYSIS MOF 2 exposes, to outer molecules, a high

number of densely packed alcohol groups, within a nanometer confined space, just as it occurs in the silanol nests of zeolites8,9. Thus, a particular acidification of adsorbed water,

promoted by the cooperativeness between nearby methyl alcohols in MOF 2, may occur. In order to discard potentially acidified water by interaction with the CuII atoms of the MOF network, the

building block Cu2II[(S,S)-serimox] was also tested as a catalyst for glycosyl hydrolysis in wet conditions, and the results showed a catalytic activity of the free CuII species one order

of magnitude lower than MOF 2 (Supplementary Fig. 22). Complementary, a filtration test showed that no leaching of active species occurs (Supplementary Fig. 23). Kinetic experiments with

different amounts of reagents and catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 24) showed that the reaction orders for MOF 2, ketal 4, and water are 1, 1, and 0, respectively, thus giving a rate equation

_v__0_ = _k__exp_[2][4]. The role of adsorbed water was further examined by dehydrating MOF 2 at 80 °C under high vacuum (10−4 mbar) during 16 h, and then performing the reaction with ketal

4 in anhydrous solvent, or adding 2 eq. of water to the reaction mixture at 60 °C. The results (Supplementary Fig. 25) show a 1/3 decrease of the hydrolysis rate compared to the original

hydrated MOF 2. These results support the catalytic action of water adsorbed in the alcohol network. Kinetic studies at different temperatures (25, 40, 60, and 80 °C) were carried out to

calculate the activation energy of the glycolysis, which according to an Arrhenius plot was 15.0 kcal mol−1. The catalysis should occur mainly inside the MOF pores rather than on its

external surface, as supported by the easier reactivity of small molecules, the saturation of the solid material with the bigger molecules and the X-ray data of the encapsulated fragments.

Computational studies were then performed to elucidate the possible mechanism of the glycosyl hydrolysis within MOF 2 (see Supplementary Methods), and the results are shown in Fig. 5. First,

ten different complexes were generated by molecular recognition of 11 into the channel of MOF 2 (Supplementary Fig. 26). Based on the applied geometrical and energetic filters (see

Supplementary Table 2), which evidenced that all the examined poses share a common orientation inside the channel of MOF 2, the best docked pose was isolated (Fig. 5a) and used as starting

structure in the Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics-Our own N-layered Integrated molecular Orbitals and Molecular mechanics (QM/MM–ONIOM) investigation (Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28).

According to the calculations, the energetically favored mechanism for the hydrolysis of 11 within MOF 2 (see Fig. 5b, c) occurs by sequential cleavage of the two acetal C–O bonds, to

release first the aromatic (R1) and then the cyclic aliphatic (R2) moieties, through the formation of intermediates bound to the serine residues (15A and 17A in Fig. 5b). The potential

energy surface (PES) related to the mechanism of Fig. 5b, black line of Fig. 5c, evidences that the hydrolysis of R1 (TS14A, 24.7 kcal mol−1) and R2 (TS16A, 26.3 kcal mol−1) occurs with

comparable barriers. The energy barriers associated with an alternative mechanism where R2 is released before R1 (Supplementary Fig. 29) and also in the absence of MOF 2 (Supplementary Fig.

30) are significantly higher in both cases. Moreover, the calculations also highlight that the increased number of serine moieties (four versus one, see red line of Fig. 5c) leads to a

lowering of the energy barriers (19.6 and 21.1 kcal mol−1, for TS14A and TS16A, respectively). This supports the synergic effect of the alcohol arms in the hydrophilic nano-confined space of

the MOF and, extrapolating to the higher number of serine moieties present within MOF 2, nicely points to the experimental value (15.0 kcal mol−1) obtained for the hydrolysis activation

energy. It must be noticed that glycosyl hydrolysis occurs in Nature by two different mechanisms, either in one-step with acid/base sites and inversion of chirality (inverting glycoside

hydrolases) or in two different steps with acid/nucleophile sites and retention of the starting chirality (retaining glycoside hydrolases). The catalytic action of MOF 2 perfectly lies on

the retaining type hydrolases, with the combined action of mild acid sites (water) and nucleophile sites (alcohols) in a confined space. DISCUSSION An amino acid-derived MOF (2), densely

decorated with methyl alcohol arms, is not only capable to hydrolyze glycosyl bonds like retaining hydrolase enzymes, without the participation of formal protons, but also to act as a vessel

encapsulating the released chiral fragment and allowing the absolute structural determination of the natural product by SCXRD. The present results constitute a clear step forward on the use

of MOFs in enzymatic catalysis41,42, where commonly their catalytic activity arises from preformed encapsulated active species. Also, let us anticipate that this bioinspired methodology

with MOFs41,43,44,45,46,47 could have future application in the MOF-driven structural characterization48,49 of more natural product structures15,50,51. METHODS PREPARATION OF 1A@2

Well-formed hexagonal green prisms of 1A@2 ((1A)@{CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-serimox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 19H2O, where 1A = 1,3,4,6-Tetra-_O_-acetylfructofuranoside), which were suitable for X-ray

diffraction, were obtained by soaking crystals of 2 (ca. 5.0 mg) in saturated water solutions of sucrose octaacetate (1), for 48 h at temperature of 50 °C. The crystals were isolated by

filtration on paper and air-dried. 1A@2: Anal.: calcd for C38Cu6CaH82N6O56 (1940.42): C, 23.52; H, 4.26; N, 4.33%. Found: C, 23.50; H, 4.21; N, 4.36%. IR (KBr): _ν_ = 1625, 1611, 1610 cm−1

(C=O). PREPARATION OF 11A@2 Well-shaped hexagonal prisms of 11A@2 ((11A)@{CaIICuII6[(_S,S_)-serimox]3(OH)2(H2O)}. 15H2O, where 11A = 6-_O_-(3′–hydroxy-3′-methylglutaryl)-glucopyranose)),

suitable for SCXRD, could be obtained by soaking crystals of 2 (which had been treated before through a solvent exchange process for a week, recharging fresh acetonitrile solvent daily) in a

saturated acetonitrile solution containing hesperetin 7-(2′′-R-rhamnosyl-6′′-(3′′′′-hydroxy-3′′′′-methylglutaryl)-glucoside) (brutieridin 11) during two weeks. After this period, crystals

were isolated by filtration and air-dried. Anal.: calcd for C36Cu6CaH74N6O52 (1844.33): C, 23.44; H, 4.04; N, 4.56%. Found: C, 23.39; H, 4.01; N, 4.57%; IR (KBr): _ν_ = 1637, 1613, 1608 cm−1

(C – O). CATALYTIC PROCEDURES MOF 2 or MOF 3 (37.5 mg, 100 wt%) were placed in a 2 ml vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar, and the corresponding amount of CD3CN (0.75 ml) was added.

Then, the corresponding amount of naringin 10 (37.5 mg) was added at room temperature. The mixture was sealed and magnetically stirred in a pre-heated oil bath at 60 °C. For kinetic

experiments, individual reactions were placed for each point and after centrifugation, the supernatant of the mixture reaction was periodically taken and analyzed by NMR. The same procedure

was followed for brutieridin 11. PREPARATION OF 13_C_ ISOTOPICALLY LABELED 11–13_C_ Brutieridin 11 (10 mg 0.013 mmol) was placed in a round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar,

and CD3CN (2 ml). Then, _N_,_N_-Diisopropylethylamine (7 μl, 0.039 mmol) and 13CH3I (5 μl, 0.078 mmol) were added via syringe at 0 °C. The mixture was sealed and magnetically stirred at room

temperature for 12 h. After that, the reaction mixture was analyzed by 13C NMR. SINGLE-CRYSTAL X-RAY DIFFRACTION Crystal data for 1A@2 and 11A@2: Hexagonal, space group _P_63, _T_ = 90(2)

K, _Z_ = 2; 1A@2: C38Cu6CaH82N6O56, _a_ = 17.7840(16) Å, _c_ = 12.5090(14) Å, _V_ = 3426.2(7) Å3, _σ_ = 1.881 g cm3, µ (mm−1) = 2.031; Absolute structure parameter (Flack) of 0.12(2). 11A@2:

C36Cu6CaH74N6O52, _a_ = 17.9667(15) Å, _c_ = 12.6886(12) Å, _V_ = 3547.2(7) Å3, _σ_ = 1.727 g cm3, µ (mm−1) = 1.953. Absolute structure parameter (Flack) of 0.13(2). Further details can be

found in the Supplementary Information. COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS The solved X-ray structure of MOF 2 has been adopted as starting point in the computational investigation. The molecular

recognition has been applied to dock substrate 11 into MOF 2, generating ten different poses. The best docked pose has been undertaken to QMMM investigations. The same computational protocol

has been previously applied in recent works. Further detailed description of the used methods is given in Supplementary Methods. DATA AVAILABILITY The authors declare that all the data

supporting the findings of this work are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray crystallographic data

reported in this study (Figs. 1, 2, and 4, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3–6 and Supplementary Table 1) have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition

numbers 1985884 (1A@2) and 1985885 (11A@2). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. CHANGE

HISTORY * _ 08 JULY 2020 An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper. _ REFERENCES * Wang, Y., Carder, H. M. & Wendlandt, A. E.

Synthesis of rare sugar isomers through site-selective epimerization. _Nature_ 578, 403–408 (2020). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shu, W., Lorente, A., Gómez-Bengoa, E. &

Nevado, C. Expeditious diastereoselective synthesis of elaborated ketones via remote Csp3–H functionalization. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 13832 (2017). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS

Google Scholar * Zhao, J.-X. et al. Structural elucidation and bioinspired total syntheses of ascorbylated diterpenoid hongkonoids A–D. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 140, 2485–2492 (2018). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Boronat, M., Martínez-Sánchez, C., Law, D. & Corma, A. Enzyme-like Specificity in zeolites: a unique site position in mordenite for selective carbonylation

of methanol and dimethyl ether with CO. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 130, 16316–16323 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lewis, J. D., Van de Vyver, S. & Román-Leshkov, Y. Acid-base

pairs in lewis acidic zeolites promote direct aldol reactions by soft enolization. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 54, 9835–9838 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ruiz, V. R. et al. Gold

catalysts and solid catalysts for biomass transformations: valorization of glycerol and glycerol–water mixtures through formation of cyclic acetals. _J. Catal._ 271, 351–357 (2010). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Corma, A., Díaz, U., García, T., Sastre, G. & Velty, A. Multifunctional hybrid organic-inorganic catalytic materials with a hierarchical system of well-defined

micro- and mesopores. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 132, 15011–15021 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fernández, A. B., Boronat, M., Blasco, T. & Corma, A. Establishing a molecular

mechanism for the Beckmann rearrangement of oximes over microporous molecular sieves. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 44, 2370–2373 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fernandez, A., Marinas,

A., Blasco, T., Fornes, V. & Corma, A. Insight into the active sites for the Beckmann rearrangement on porous solids by in situ infrared spectroscopy. _J. Catal._ 243, 270–277 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Carceller, J. M. et al. Selective synthesis of citrus flavonoids prunin and naringenin using heterogeneized biocatalyst on graphene oxide. _Green. Chem._ 21,

839–849 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, M. et al. Genesis and stability of hydronium ions in zeolite channels. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 141, 3444–3455 (2019). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Murphy, B. M. et al. Nature and catalytic properties of in-situ-generated brønsted acid sites on NaY. _ACS Catal._ 9, 1931–1942 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Huffman, M. A. et al. Design of an in vitro biocatalytic cascade for the manufacture of islatravir. _Science_ 366, 1255–1259 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Furukawa,

H., Cordova, K. E., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. _Science_ 341, 974 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bloch, W. M.,

Champness, N. R. & Doonan, C. J. X-ray crystallography in open-framework materials. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 54, 12860–12867 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cohen, S. M. The

postsynthetic renaissance in porous solids. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 2855–2863 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grancha, T. et al. Postsynthetic improvement of the physical

properties in a metal-organic framework through a single crystal to single crystal transmetallation. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 54, 6521–6525 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pei, X.,

Bürgi, H.-B., Kapustin, E. A., Liu, Y. & Yaghi, O. M. Coordinative alignment in the pores of MOFs for the structural determination of N-, S-, and P-containing organic compounds including

complex chiral molecules. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 141, 18862–18869 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mon, M. et al. Solid-state molecular nanomagnet inclusion into a magnetic

metal-organic framework: interplay of the magnetic properties. _Chem. Eur. J._ 22, 539–545 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Inokuma, Y., Arai, T. & Fujita, M. Networked

molecular cages as crystalline sponges for fullerenes and other guests. _Nat. Chem._ 2, 780–783 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kersten, R. D. et al. A red algal bourbonane

sesquiterpene synthase defined by microgram-scale NMR-coupled crystalline sponge X-ray diffraction analysis. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 16838–16844 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Lee, S., Hoshino, M., Fujita, M. & Urban, S. Cycloelatanene A and B: absolute configuration determination and structural revision by the crystalline sponge method. _Chem. Sci._ 8,

1547–1550 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Matsuda, Y. et al. Astellifadiene: structure determination by nmr spectroscopy and crystalline sponge method, and elucidation of its

biosynthesis. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 55, 5785–5788 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tejeda-Serrano, M. et al. Isolated Fe(III)–O sites catalyze the hydrogenation of acetylene in

ethylene flows under front-end industrial conditions. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 140, 8827–8832 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rivero-Crespo, M. A. et al. Confined Pt 1 1+ water

clusters in a MOF catalyze the low-temperature water-gas shift reaction with both CO2 oxygen atoms coming from water. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 57, 17094–17099 (2018). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Mon, M. et al. Synthesis of densely packaged, ultrasmall Pt 0 2 clusters within a thioether-functionalized MOF: catalytic activity in industrial reactions at low temperature.

_Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 57, 6186–6191 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mon, M. et al. Stabilized Ru[(H2O)6]3+ in confined spaces (MOFs and zeolites) catalyzes the imination of primary

alcohols under atmospheric conditions with wide scope. _ACS Catal._ 8, 10401–10406 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fortea-Pérez, F. R. et al. The MOF-driven synthesis of supported

palladium clusters with catalytic activity for carbene-mediated chemistry. _Nat. Mater._ 16, 760–766 (2017). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Bruno, R. et al. Highly efficient

temperature-dependent chiral separation with a nucleotide-based coordination polymer. _Chem. Commun._ 54, 6356–6359 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mon, M. et al. Crystallographic

snapshots of host–guest interactions in drugs@metal–organic frameworks: towards mimicking molecular recognition processes. _Mater. Horiz._ 5, 683–690 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Mon, M. et al. Efficient capture of organic dyes and crystallographic snapshots by a highly crystalline amino-acid-derived metal-organic Framework. _Chem. Eur. J._ 24, 17712–17718 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Aulakh, D. et al. Metal–organic frameworks as platforms for the controlled nanostructuring of single-molecule magnets. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 137,

9254–9257 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hayes, L. M. et al. The crystalline sponge method: a systematic study of the reproducibility of simple aromatic molecule

encapsulation and guest–host interactions. _Cryst. Growth Des._ 16, 3465–3472 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mon, M. et al. Lanthanide discrimination with hydroxyl-decorated

flexible metal–organic frameworks. _Inorg. Chem._ 57, 13895–13900 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhao, J., Yuan, Y., Meng, X., Duan, L. & Zhou, R. Highly efficient

liquid-phase hydrogenation of naringin using a recyclable Pd/C catalyst. _Mater. (Basel)._ 12, 46 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Di Donna, L. et al. Statin-like principles of

Bergamot fruit (Citrus bergamia): isolation of 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl flavonoid glycosides. _J. Nat. Prod._ 72, 1352–1354 (2009). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Cicero, A. F. G. et

al. Lipid lowering nutraceuticals in clinical practice: position paper from an International Lipid Expert Panel. _Arch. Med. Sci._ 5, 965–1005 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Sindona, G., Di Donna, L. & Dolce, V. Natural molecules extracted from bergamot tissues, extraction process and pharmaceutical use. PCT/EP2012/2424545, WO2010/041290 (A1) (2010). *

Istvan, E. S. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. _Science_ 292, 1160–1164 (2001). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Davies, G. & Henrissat, B.

Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. _Structure_ 3, 853–859 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gkaniatsou, E. et al. Metal–organic frameworks: a novel host platform

for enzymatic catalysis and detection. _Mater. Horiz._ 4, 55–63 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, K. & Wu, C.-D. Designed fabrication of biomimetic metal–organic frameworks

for catalytic applications. _Coord. Chem. Rev._ 378, 445–465 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fracaroli, A. M. et al. Seven post-synthetic covalent reactions in tandem leading to

enzyme-like complexity within metal–organic framework crystals. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 138, 8352–8355 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Baek, J. et al. Bioinspired

metal–organic framework catalysts for selective methane oxidation to methanol. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 140, 18208–18216 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wright, A. M. et al. A

structural mimic of carbonic anhydrase in a metal-organic framework. _Chem_ 4, 2894–2901 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lian, X. et al. Enzyme–MOF (metal–organic framework)

composites. _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 46, 3386–3401 (2017). Article MathSciNet CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Doonan, C., Riccò, R., Liang, K., Bradshaw, D. & Falcaro, P. Metal–organic

frameworks at the biointerface: synthetic strategies and applications. _Acc. Chem. Res._ 50, 1423–1432 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Young, R. J. et al. Isolating reactive

metal-based species in metal–organic frameworks–viable strategies and opportunities. _Chem. Sci._ 11, 4031–4050 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Viciano-Chumillas, M. et al.

Metal–organic frameworks as chemical nanoreactors: synthesis and stabilization of catalytically active metal species in confined spaces. _Acc. Chem. Res._ 53, 520–531 (2020). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Jones, C. G. et al. The CryoEM method MicroED as a powerful tool for small molecule structure determination. _ACS Cent. Sci._ 4, 1587–1592 (2018). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structures of atomic surfaces and host-guest chemistry in metal-organic frameworks. _Matter_ 1, 428–438 (2019). Article

Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (Italy) and the MINECO (Spain) (Projects

CTQ2016-75671-P, CTQ 2017-86735-P, RTC-2017-6331-5, Severo Ochoa program SEV-2016-0683 and Excellence Unit “Maria de Maeztu” MDM-2015-0538). R.B. thanks the MIUR (Project PON R&I

FSE-FESR 2014–2020) for grant. L.B wishes to thank Italian MIUR for grant n. AIM1899391–1 in the framework of the project “Azione I.2, Mobilità dei Ricercatori, PON R&I 2014–2020”.

Thanks are also extended to the “2019 Post-doctoral Junior Leader-Retaining Fellowship, la Caixa Foundation (ID100010434 and fellowship code LCF/BQ/PR19/11700011” (J. F.-S.). S. S.-N. thanks

ITQ for the concession of a contract. D.A. acknowledges the financial support of the Fondazione CARIPLO/“Economia Circolare: ricerca per un futuro sostenibile” 2019, Project code:

2019–2090, MOCA. E.P. acknowledges the financial support of the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program/ERC Grant Agreement No.

814804, MOF-reactors. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Marta Mon, Rosaria Bruno, Sergio Sanz-Navarro. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Instituto de Ciencia

Molecular (ICMol), Universidad de Valencia, 46980, Paterna, Valencia, Spain Marta Mon, Cristina Negro, Jesús Ferrando-Soria & Emilio Pardo * Dipartimento di Chimica e Tecnologie Chimiche

(CTC), Università Della Calabria, 87036, Rende, Cosenza, Italy Rosaria Bruno, Lucia Bartella, Leonardo Di Donna, Mario Prejanò, Tiziana Marino & Donatella Armentano * Instituto de

Tecnología Química (UPV–CSIC), Universitat Politècnica de València–Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Avenida de los Naranjos s/n, 46022, Valencia, Spain Sergio Sanz-Navarro

& Antonio Leyva-Pérez Authors * Marta Mon View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rosaria Bruno View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sergio Sanz-Navarro View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cristina Negro View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jesús Ferrando-Soria View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lucia

Bartella View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Leonardo Di Donna View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Mario Prejanò View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tiziana Marino View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Antonio Leyva-Pérez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Donatella Armentano View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Emilio Pardo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Author contributions are as

follows: M.M. and C.N. performed the synthesis and characterization of MOFs 2 and 3. R.B. and C.N. carried out the preparation of the host–guest materials. S.S.-N. performed the catalytic

experiments. A. L.-P. supervised the catalytic part. L.D.D. and L.B. carried out the extraction of natural brutieridin. M.P. and T.M. carried out the theoretical calculations; D.A. was in

charge of the structural resolution. E.P., J.F.-S., A.L.-P., and D.A. coordinated the whole work and wrote the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Jesús Ferrando-Soria,

Antonio Leyva-Pérez, Donatella Armentano or Emilio Pardo. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION

_Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and

your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this

license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Mon, M., Bruno, R., Sanz-Navarro, S. _et al._ Hydrolase–like

catalysis and structural resolution of natural products by a metal–organic framework. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3080 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16699-3 Download citation * Received:

16 March 2020 * Accepted: 13 May 2020 * Published: 17 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16699-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to

read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative