Why do people seek out polygenic risk scores for complex disorders, and how do they understand and react to results?

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT We sought to explore individuals’ motivations for using their direct-to-consumer genetic testing data to generate polygenic risk scores (PRSs) using a not-for-profit third-party

tool, and to assess understanding of, and reaction to their results. Using a cross-sectional design, users of Impute.me who had already accessed PRS results were invited to complete an

online questionnaire asking about demographics, motivations for seeking PRSs, understanding and interpretation of PRSs, and two validated scales regarding reactions to results—the Impact of

Event Scale Revised (IES-R) and the Feelings About genomiC Testing Results (FACToR). Independent samples _T_-tests and ANOVA were used to explore associations between the variables. 227

individuals participated in the study. The most frequently reported motivation was general curiosity (98.2%). Only 25.6% of participants correctly answered all questions assessing

understanding/interpretation of PRSs. Over half of participants (60.8%) experienced a negative reaction (upset, anxious, and/or sad on FACToR scale) after receiving their PRSs and 5.3%

scored over the threshold for potential post-traumatic stress disorder on the IES-R. Lower understanding about PRS was associated with experiencing a negative psychological reaction (_P_

values <0.001). Higher quality pre-test information, particularly to improve understanding, and manage expectations for PRS may be useful in limiting negative psychological reactions. You

have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS RISK PERCEPTION AND INTENDED BEHAVIOR CHANGE AFTER UNINFORMATIVE GENETIC RESULTS

FOR ADULT-ONSET HEREDITARY CONDITIONS IN UNSELECTED PATIENTS Article 26 September 2023 WHAT PEOPLE REALLY CHANGE AFTER GENETIC TESTING (GT) PERFORMED IN PRIVATE LABS: RESULTS FROM AN ITALIAN

STUDY Article Open access 12 April 2021 KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES AND DEMAND TOWARD CARDIOVASCULAR POLYGENIC RISK TESTING IN CLINICAL PRACTICE: CROSS-SECTIONAL SURVEY OF PATIENTS Article 07

December 2024 INTRODUCTION Most common conditions that affect humans are etiologically complex, with the genetic risk being conferred by an accumulation of many genetic variants of small

effect [1]. These variants can be summarized into a single variable, a polygenic risk score (PRS), that measures the genetic contribution for a given trait or condition. While for most

disorders PRSs are not yet being used in clinical practice [2], they are likely to become a more routine part of clinical care in the future [1]. However in the meantime, public interest in

genetic information has led companies that already provide direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing online [3,4,5] to include PRSs in their offerings. Third-party services have also emerged

which allow users to upload their raw personal genetic information obtained from DTC sites (like 23andMe or Ancestry) and generate PRSs for a wide variety of conditions [6]. Emerging data

demonstrate very rapid increase in the usage of these third-party sites [6]. Despite the rapid growth in rate with which people are accessing their own PRSs without the involvement of a

healthcare provider [6], little is known about what motivates people to seek this information, or how they understand and react to the results that they receive. Historically, patient

outcomes of genetic testing have been found to be generally benign, however, most studies have focused on individuals who were known to be at high-risk for a monogenic disease based on

personal or family history [7, 8]. Importantly, the majority of studies assessing the emotional impacts of genetic testing have been conducted in a clinical context that was accompanied by

genetic counseling [7, 8]. There have been studies which have focused on outcomes of DTC genetic testing, although the majority have not explored the experiences of actual consumers and

instead used hypothetical scenarios or provided free ‘DTC’ genetic testing for recruited participants [9,10,11]. A number of these studies have suggested the potential for slight negative

reactions, however, current research that has examined actual reactions to DTC tests is limited and remains less clear [11]. There is a small but growing body of literature about

individuals’ reactions to receiving PRSs, however these studies have predominantly focused on recruiting people to receive PRSs for specific conditions (e.g., cancer) for which the

participants already had increased risk due to personal or family history and the PRS results were delivered in the context of carefully designed interventions [12,13,14,15]. To our

knowledge, only one study has explored the impact of a variety of PRSs on individuals who were not specifically at risk for a particular condition. In this study, participants were recruited

from the staff of health and technology companies, and education, informed consent, and genetic counseling about PRSs accompanied the testing [16]. There is very little known about the

experiences of our population of interest, where individuals are self-initiating the process of seeking out PRSs and uploading their DTC genetic testing data into third-party websites to

access this information for themselves. We sought to elicit motivations for seeking PRSs, understanding of the results, and psychological reactions to receiving this information among

individuals who had sought out PRSs for themselves by uploading their own raw genetic testing data into a third-party PRS website. MATERIALS AND METHODS RECRUITMENT Participants were

recruited from users of Impute.me; a third-party non-profit tool that provides PRSs for 166 different conditions from personalized raw genetic data (e.g., generated by 23andMe) to users at

no cost. The website (https://www.impute.me) was established in 2015 and is run by independent academics. Impute.me has strict privacy standards; all personally traceable and non-traceable

genetic information is deleted two weeks and two years after imputation, respectively [6]. Users upload their raw genetic data to Impute.me and access the complex disorders module on the

website to receive polygenetic risk scores for a variety of traits and conditions. The user chooses which conditions to query and after performing five or more queries on the website’s

complex disorders module with their personal results, users were invited to complete a questionnaire on the REDCap [17] platform via a pop-up banner containing a link. Individuals were

eligible to participate if they: (1) had received PRS results from the Impute.me website for at least five complex disorders and were (2) at least 18 years of age, and (3) fluent in English.

The study was launched in June 2019 and data collection ended in April 2020. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board (H19-00427). For more

information on how PRS are provided by Impute.me, we have included sample reports in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). QUESTIONNAIRE The questionnaire contained

three main sections: users’ motivations for seeking PRSs, their understanding and interpretation of the results, and the psychological impacts of receiving this information (see

Supplementary materials). The survey also included demographic items (age, sex, gender, ethnicity, education level, household income, history of psychiatric illness, and the time elapsed

since participants received their results from Impute.me, see Table 1) and a three-item numeracy scale previously found to have acceptable reliability [18]. The survey did not collect or

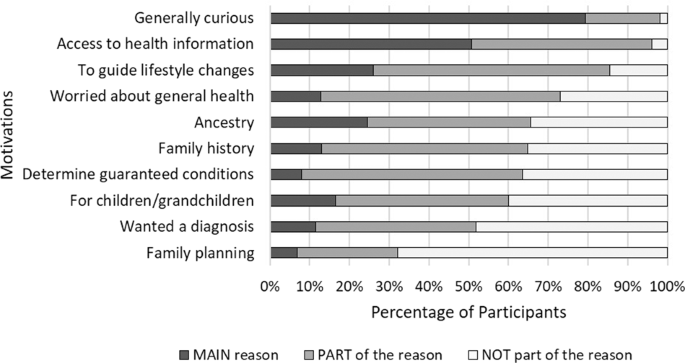

link responses to the participants’ PRS data. MOTIVATIONS To explore motivations for seeking PRS information, participants were asked to rate ten items (see Fig. 1) on a four-point Likert

scale ranging from “this was NOT part of the reason for me to upload my data to Impute.me” to “this was the MAIN reason for me to upload my data to Impute.me”. During data analysis the

middle categories were combined to form a new category: “PART of the reason”. Participants were provided a list of the 58 most inquired-about conditions (those reviewed by ≥25% of all users)

and asked to select those for which they were initially interested in learning about their risk. Because individual PRS results were not linked to the survey responses, we used this

question to explore if there were specific conditions that motivated interest in PRSs. There were also two free text items regarding initial motivations. UNDERSTANDING AND INTERPRETATION OF

RESULTS Participants’ _understanding_ of the meaning of the PRS results was explored with three true/false statements (see Table 2), and to assess _interpretation_ of PRS result information,

participants were provided an example Impute.me PRS result, and asked to answer five true/false statements. REACTIONS We used two established scales to explore psychological reactions to

PRSs, the Feelings About genomiC Testing Results (FACToR) questionnaire, and the Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R). Wording for both instructed participants to use the receipt of the PRS

results as the reference point for answering the items. The FACToR scale is a 12 item, preliminarily validated [19] tool adapted from the MICRA scale [20] that contains four subscales:

Negative Emotions, Positive Feelings, Uncertainty and Privacy Concerns. Summary scores for each subscale are calculated by adding scores from individual items in that subscale, with possible

scores ranging from 0-12 for the Negative Emotions and Uncertainty Subscales, 0-16 on the Positive Feelings Subscale, and 0-8 on the Privacy Concerns Subscale. For items that measure

positive feelings, scores were first reversed before being summed, such that for all scales, a higher score indicates greater functional impairment [19]. We focused on the negative emotions

subscale because understanding factors that contribute to patient harm has the greatest likelihood to impact clinical practice around the delivery of PRS information. The IES-R is a 22 item

validated instrument [21] that assesses subjective distress associated with events. IES-R scale scores range from 0 to 88, with a score >23 indicating likely clinically significant

distress, scores between 33 and 38 suggesting a probable diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and scores >38 indicating significant PTSD [21]. DATA ANALYSIS Analysis was

primarily descriptive, but given the clinical importance of negative reactions to PRS, we used exploratory statistical tests to examine relationships between these reactions and other

variables. Specifically, we explored relationships between the IES-R and FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale scores and demographic variables using independent samples _t_ tests and ANOVA,

with post-hoc Tukey to further explore significant relationships. We also compared IES-R and FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale scores between those who did/did not: (a) chose “curiosity” as

a main reason for seeking their PRS, (b) answer all of the numeracy questions correctly, (c) answer all three of the understanding questions correctly, and d) answer all five of the

interpretation questions correctly (independent sample _t_ tests). As well, we explored relationships between the number of motivators participants selected and, first, IES-R (those who

scored above and below cutoff for PTSD), and second, FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale score (independent samples _t_ tests, and Pearson correlation/linear regression respectively). All

statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). Although this was an exploratory study, we used a conservative approach, and set our

threshold for statistical significance at _p_ < 0.002 (Bonferroni correction accounting for the 26 tests we conducted). Text that participants provided in the free-form text fields was

used to provide illustrative quotes around key findings. RESULTS Of the 10,650 people who were eligible to participate, 438 (4.1%) clicked on the link for more information and 277

participated in the study (2.6% of eligible). Respondents tended to be female (_n_ = 144, 63.7%), White (_n_ = 200, 88.5%), with high levels of education (_n_ = 121, 53.3 % had a bachelor’s

or graduate degree), and most (_n_ = 162, 71.7%) had received their results for the first time within the week prior to completing the questionnaire (see Table 1). Incomplete surveys were

included in analysis and therefore response rate varied by question. MOTIVATIONS Almost all participants indicated that general curiosity (_n_ = 270, 98.2%) and accessing additional health

information (_n_ = 265, 96.0%) were at least part of their reason for seeking PRSs (see Fig. 1). The conditions that were most frequently identified by participants as being of interest

included Alzheimer’s disease (_n_ = 127, 50.0%), anxiety disorder (_n_ = 105, 41.3%), major depressive disorder (_n_ = 98, 38.6%), type 2 diabetes (_n_ = 97, 38.2%), and breast cancer (_n_ =

81, 31.9%). Free-text responses for motivations to pursue PRS information were generally consistent with results shown in Fig. 1. Although the free-text responses were not formally

analyzed, three main concepts were mentioned by multiple respondents including (i) their personal curiosity about genetic information (e.g., “_Curious about heritability of traits linked to

psychology and personality”_), (ii) personal diagnoses or undiagnosed health conditions which they wanted to learn more about (e.g., “_Currently dealing with medical problems that my doctors

cannot figure out… hoping my DNA would explain_”), and iii) adoptions in the family that drove their investigations (e.g., _“I’m adopted, I have no idea what my family history is… this is a

chance to have some idea”_). UNDERSTANDING AND INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS Regarding general _understanding_ of the meaning of PRSs, 35.5% (_n_ = 93) of participants incorrectly classified

one or more statements (see Table 2). When asked to _interpret_ an example Impute.me result, 61.6% (_n_ = 149) of participants incorrectly identified one or more statements. Overall, only

25.6% (_n_ = 67) of participants answered all understanding and interpretation questions correctly. REACTIONS Given that negative reactions to genetic information are of clinical interest,

we explored the Negative Emotions Subscale further. Average scores for each of the four FACToR subscales are shown in Supplementary Table 1, and overall spread of scores is shown in

Supplementary Fig. 3. We assessed the proportion of respondents who reported that they experienced a negative reaction (upset, anxious and/or sad) either a little, somewhat, a good deal or a

great deal after receiving their personal PRSs. Overall, 60.8% of participants (_n_ = 146) reported that they experienced a negative reaction. Of those participants, 14.4% (_n_ = 21; 8.8%

of total participants) reported that they experienced one or more of those negative reactions either a good or great deal. The mean IES-R score was 5.38 ± 10.0, and most participants (94.7%,

_n_ = 213) had a total score of 23 or below. Of the remaining 5.3% (_n_ = 12), 33% (_n_ = 4) scored less than 33 (indicating clinically significant distress), 17% (_n_ = 2) scored between

33 and 38 (indicating a probable diagnosis of PTSD), and 50% (_n_ = 6) scored above 38 (indicating significant PTSD). Every participant who scored above the IES-R cut-off of 23 also reported

some degree of negative reaction on the FACToR. Overall spread of scores is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. VARIABLES ASSOCIATED WITH NEGATIVE REACTIONS DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES There was 99%

concordance between sex and gender of participants, and the statistical analyses of these variables resulted in the same findings. No association (all _p_ values > 0.002) was found

between any demographic characteristic and the psychological impact of receiving PRSs (Table 1). Regarding numeracy, the mean FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale scores of participants who did

not get all three numeracy questions correct (mean = 2.5, SD = 3.3) was significantly higher (_t_(43.8) = −3.2, _p_ = 0.002) than those who did (mean = 1.3, SD = 1.6). Reaction scores for

each of the most commonly inquired-about conditions offered on Impute.me are shown in Supplementary Table 2. UNDERSTANDING AND INTERPRETATION OF PRSS We identified significant relationships

between understanding of and reactions to the PRS test as measured by FACToR and IES-R (Fig. 2). Specifically, the mean FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale score for participants who did not

get all three understanding questions correct (2.7 ± 3.2) was significantly higher ((_t_(29.9) = 3.3, _p_ = 0.001) than those who did get all three correct (1.4 ± 1.9). Similarly, the mean

IES-R score for participants who did not get all three understanding questions correct (10.2 ± 14.8) was significantly higher ((_t_(59.6) = 4.1, _p_ < 0.001)) than those who did get all

three correct (2.9 ± 5.3). However, there was no relationship between the number of questions about interpretation of an example PRS result that was correctly answered and either FACToR

Negative Emotions Subscale scores or IES-R scores (_p_ = 0.21, and _p_ = 0.15, respectively). MOTIVATIONS FOR SEEKING PRSS The average FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale and IES-R scores for

the 10 different motivations for seeking PRS information are shown in Fig. 3. The motivations were not mutually exclusive (people could select as many as they liked). We found that

individuals who _did not_ choose curiosity as a main reason for seeking out their PRS scores had statistically significantly higher IES-R scores (mean = 10.3, SD = 16.6) and FACToR Negative

Emotions Subscale scores (mean = 2.7, SD = 3.1) compared to those who chose curiosity as a main reason for seeking out their PRS scores (IES-R; mean = 4.1, SD = 7.2, FACToR; mean = 1.6, SD =

2.2). IES-R; (_t_(33.4) = −3.8, _p_ ≤ 0.001). FACToR; (_t_(3.8) = −2.7, _p_ = 0.009). We found a small correlation between the number of motivations chosen and higher FACToR Negative

Emotions Subscale scores (_R_2 = 0.122), and the number of motivations chosen predicted 35.5% of the FACToR Negative Emotions Subscale score (_B_ = 0.355, _p_ < 0.001). Similarly, we

found that participants who scored above threshold for PTSD on the IES-R scale chose more motivations (mean = 8.4, SD = 1.0) than those who scored below the threshold (mean = 6.7, SD = 1.8)

(_t_(4.2) = −5.3, _p_ ≤ 0.001). DISCUSSION Our study involved individuals who self-initiated the process of seeking out PRSs by uploading their DTC genetic testing data into a third-party

website to access this information for themselves. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the motivations for seeking PRSs, understanding and interpretation of the results,

and reactions to receiving this information among this type of user. We found that over 60% of participants experienced some degree of negative reaction after receiving their personal PRSs,

and ~5% scored over the threshold for potential PTSD. We found that having poorer understanding of PRS, being motivated by reasons other than general curiosity to seek out this information,

having lower levels of numeracy, and reporting more motivations for seeking out PRS were related to having a negative psychological impact of PRS information. It is important to note that

the cohort of participants in this study is early adopters of PRS who overcame financial and logistical barriers to seek out this information for themselves. This is relevant to bring

attention to because the participants in our study likely do not represent how the average member of the public would respond to this type of information, and our findings may underestimate

the potential harms of PRSs in a broader population. It is well known that numerical risks are both easily misinterpreted (due to common scientific and mathematical limitations) as well as

subjectively perceived (personal experiences that can impact one’s risk perception) [22]. In our study population, lower numeracy was associated with having a negative reaction to PRS

information. There are unique challenges in communicating PRSs, not only are they probabilistic rather than deterministic, but also they are usually presented as risk stratifications or

relative risks compared to the general population [22]. Theoretically, if people misunderstand PRS results, and assume that lifestyle plays no role in disease risk, this could have important

impacts on engagement with risk reduction behaviors. More information is needed regarding how to effectively communicate relative and absolute risks to patients and consumers, and to

determine if improved communication about risk improves experience with complex genetic information. Our findings suggest that many participants had some understanding about the general

concepts of multifactorial/complex conditions and PRSs, and this has been similarly reflected in other recent studies [23,24,25]. However, many participants in this study had incomplete

understanding and interpretation of PRS, as demonstrated by 74.4% of participants incorrectly answering at least one of the questions in this area. Poorer understanding of PRSs was

associated with experiencing a negative reaction from receiving the information. There are a number of solutions that could be employed to increase understanding and interpretation of PRS

results including more pretest education, changes in data visualization or presentation to make the results easier to understand and more meaningful for users, and involvement of a genetic

counselor or other healthcare providers in pretest and/or results disclosure of PRSs. One example of improved data visualization for PRS communication that could be implemented in the future

is the use of dynamic visuals and additional information about normal distribution curves that is present on this website (http://polygenicscores.org/explained/). Prior to considering the

implementation of PRSs as a screening tool, health systems must consider the infrastructure and personnel required for service delivery without causing patient harm. A major motivation for

participants seeking their PRS in this study was curiosity, and while there are no studies with which to compare directly, this is observation is broadly consistent with studies of why

people upload their DTC genetic testing data to other types of third-party genetic interpretation platforms [23, 26]. We found that when participants chose curiosity as a main motivation for

seeking out PRS information, they were less likely to experience a negative reaction from this information. Similar findings exist in the literature, specifically, in a study of people’s

reactions to receiving _non-PRS_ third-party interpretation of their genetic information, recipients whose motivation was curiosity were more satisfied than recipients who pursued

interpretation of genetic information for health-related reasons [27]. We also found that individuals who experienced negative reactions chose more motivations for seeking out their PRSs

compared to those who did not have negative reactions. A possible explanation for this finding is that individuals who had more unmet needs or higher expectations for the types and certainty

of results they could get from PRS were more likely to experience a negative reaction. Due to the nature of our study, we were unable to explore this relationship further and it could be of

interest for future research studies. This study has several limitations. The demographic make-up of our participants was self-selected and homogenous and the findings from our study may

not capture the breadth of experiences of all individuals, particularly since there are limitations for PRS data in non-white populations further research should be done to specifically

investigate these study questions in a more diverse population. We asked about participants’ motivations for seeking PRSs after they had already reviewed their results, which may have led to

imperfect recall in this section of the questionnaire. Our sample also includes mainly participants who received their results within one week of answering the questionnaire and therefore

cannot be used to draw conclusions about long-term effects of receiving PRSs. Additionally, without the demographic information from non-responders; it is difficult to say whether there may

have been sample bias. It is possible that users who felt more strongly about their results may have been more likely to participate in our study, or conversely, that those who were feeling

more distraught about their results may have been less inclined to participate. Although the IES and FACToR scales specifically ask about and were anchored on participants’ experience with

genetic information, it is possible that there were other confounding factors that contributed to individuals’ having a negative reaction to PRS information that are beyond the relationships

explored through the demographic variables. Lastly, as this was a retrospective study and Impute.me is committed to providing confidential results, we were unable to correlate these

responses with the level of risk for individuals. Future research is needed in this area on more a diverse demographic sample, as our study included those who were self-selected and may have

under-represented harms. It is also possible that there is a more complex relationship between the variables that were explored in this study and future research could undertake a more

complex multivariable model to better understand how these variables may or may not predict a negative reaction to PRS information. In addition, future studies should explore how outcomes

are related to actual and perceived genetic risk levels, which will be important to understand as PRSs become more utilized in both clinical and population-level screening. There is also the

opportunity to perform qualitative research in this area to better understand the individual experiences of receiving PRSs. Lastly, because we have shown that people with lesser

understanding about PRSs are more likely to experience negative reactions, future research should compare outcomes after providing more comprehensive pre-analysis information to consumers.

CONCLUSION The need to understand motivations for seeking, understanding and interpretation of, and reactions to PRSs becomes increasingly urgent as we look to a future where these types of

risk estimates are used regularly in clinical care, population screening, and consumer settings. Higher quality pretest education, particularly to address the limitations of PRSs and more

effectively communicate the differences between relative and absolute risks, may mitigate the risk of negative psychological reactions in response to receiving personal PRSs. Although our

study sample originates from a consumer genetics population, our results could inform the use of PRSs in clinical practice, as the data we have gathered here can help inform the development

of effective communication strategies of PRSs, with the ultimate goal of improving care as PRSs become more prevalent in both consumer and clinical settings. REFERENCES * Torkamani A,

Wineinger NE, Topol EJ. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:581–90. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lewis CM, Vassos E. Prospects for using

risk scores in polygenic medicine. Genome Med. 2017;9:96. Article Google Scholar * NorthShore University HealthSystem. Prostate Cancer Genetic Risk Score. 2016.

https://www.helix.com/products/prostate-cancer-genetic-risk-score (accessed 15 Nov 2019). * Multhaup ML, Kita R, Krock B, Eriksson N, Fontanillas P, Aslibekyan S, et al. White Paper 23-19:

The science behind 23andMe’s Type 2 Diabetes report. 2019. https://permalinks.23andme.com/pdf/23_19-Type2Diabetes_March2019.pdf * Janssens ACJW. Proprietary algorithms for polygenic risk:

protecting scientific innovation or hiding the lack of it? Genes. 2019;10:448. Article CAS Google Scholar * Folkersen L, Pain O, Ingason A, Werge T, Lewis CM, Austin J. Impute.me: an

open-source, non-profit tool for using data from direct-to-consumer genetic testing to calculate and interpret polygenic risk scores. Front Genet. 2020;11:578. Article CAS Google Scholar

* Heshka JT, Palleschi C, Howley H, Wilson B, Wells PS. A systematic review of perceived risks, psychological and behavioral impacts of genetic testing. Genet Med. 2008;10:19–32. Article

Google Scholar * Oliveri S, Ferrari F, Manfrinati A, Pravettoni G. A systematic review of the psychological implications of genetic testing: a comparative analysis among cardiovascular,

neurodegenerative and cancer diseases. Front Genet. 2018;9:624. Article CAS Google Scholar * Roberts JS, Ostergren J. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing and personal genomics services: a

review of recent empirical studies. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2013;1:182–200. Article Google Scholar * Covolo L, Rubinelli S, Ceretti E, Gelatti U. Internet-based direct-to-consumer genetic

testing: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e279. Article Google Scholar * Stewart KFJ, Wesselius A, Schreurs MAC, Schols AMWJ, Zeegers MP. Behavioural changes, sharing

behaviour and psychological responses after receiving direct-to-consumer genetic test results: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Community Genet.2018;9:1–18. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Bancroft EK, Castro E, Bancroft GA, Ardern-Jones A, Moynihan C, Page E, et al. The psychological impact of undergoing genetic-risk profiling in men with a family history of

prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1492–9. Article Google Scholar * Young MA, Forrest LE, Rasmussen VM, James P, Mitchell G, Sawyer SD, et al. Making sense of SNPs: women’s

understanding and experiences of receiving a personalized profile of their breast cancer risks. J Genet Couns 2018;27:702–8. Article Google Scholar * Putt S, Yanes T, Meiser B, Kaur R,

Fullerton JM, Barlow-Stewart K, et al. Exploration of experiences with and understanding of polygenic risk scores for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:342–50. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Yanes T, Kaur R, Meiser B, Scheepers-Joynt M, McInerny S, Barlow-Stewart K, et al. Women’s responses and understanding of polygenic breast cancer risk information. Fam Cancer.

2020;19:297–306. Article CAS Google Scholar * Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:524–34.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process

for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. Article Google Scholar * Schwartz L, Woloshin S, Black W, Welch H. The role of numeracy in

understanding the benefit of screenning mamography. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:966–72. Article CAS Google Scholar * Li M, Bennette CS, Amendola LM, Ragan Hart M, Heagerty P, Comstock B, et

al. The Feelings About genomiC Testing Results (FACToR) questionnaire: development and preliminary validation. J Genet Couns 2019;28:477–90. Article Google Scholar * Cella D, Hughes C,

Peterman A, Chang CH, Peshkin BN, Schwartz MD, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA)

questionnaire. Health Psychol. 2002;21:564–72. Article Google Scholar * Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale—revised. In: Wilson J, Keane TM (eds). _Assessing psychological

trauma and PTSD_. Guilford: New York, 1996, pp 399–411. * Lautenbach DM, Christensen KD, Sparks JA, Green RC. Communicating genetic risk information for common disorders in the era of

genomic medicine. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:491–513. Article CAS Google Scholar * Gollust SE, Gordon ES, Zayac C, Griffin G, Christman MF, Pyeritz RE, et al. Motivations and

perceptions of early adopters of personalized genomics: perspectives from research participants. Public Health Genom. 2012;15:22–30. Article CAS Google Scholar * McBride CM, Alford SH,

Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Characteristics of users of online personalized genomic risk assessments: Implications for physician-patient interactions. Genet Med.

2009;11:582–7. Article Google Scholar * Gordon ES, Griffin G, Wawak L, Pang H, Gollust SE, Bernhardt BA. ‘It’s not like judgment day’: public understanding of and reactions to personalized

genomic risk information. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:423–32. Article Google Scholar * Su Y, Howard HC, Borry P. Users’ motivations to purchase direct-to-consumer genome-wide testing: an

exploratory study of personal stories. J Community Genet. 2011;2:135–46. Article Google Scholar * Wang C, Cahill TJ, Parlato A, Wertz B, Zhong Q, Cunningham TN, et al. Consumer use and

response to online third-party raw DNA interpretation services. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2018;6:35–43. Article Google Scholar Download references FUNDING This study was funded by the

University of British Columbia and was conducted to fulfill a degree requirement as part of training. JA was supported by the Canada Research Chairs program and the BC Mental Health and

Substance Use Services. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Larissa Peck &

Jehannine Austin * London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada Larissa Peck * Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia,

Canada Kennedy Borle * Institute of Biological Psychiatry, Mental Health Centre Sankt Hans, Copenhagen, Denmark Lasse Folkersen * Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia,

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Jehannine Austin Authors * Larissa Peck View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kennedy Borle View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lasse Folkersen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jehannine

Austin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS LP, KB, and JA contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of the

data, and the drafting, revision and final approval of the manuscript. LF was consulted on the design of the study and contributed to the revision and final approval of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Jehannine Austin. ETHICS DECLARATIONS ETHICAL APPROVAL All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of

British Columbia. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board

(H19‐00427). COMPETING INTERESTS LP, KB, and JA declare no conflict of interest. Dr. Lasse Folkersen is the founder of Impute.me but does not make a profit from this service. The voluntary

donations received by Impute.me go to a registered company, from where it is used to pay for server costs. The company is a Danish-law IVS company with ID 37918806, financially audited under

Danish tax law. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION QUESTIONNAIRE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Peck, L., Borle, K., Folkersen, L. _et al._ Why do

people seek out polygenic risk scores for complex disorders, and how do they understand and react to results?. _Eur J Hum Genet_ 30, 81–87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00929-3

Download citation * Received: 21 February 2021 * Revised: 18 May 2021 * Accepted: 17 June 2021 * Published: 19 July 2021 * Issue Date: January 2022 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00929-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative