The dutch y-chromosomal landscape

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Previous studies indicated existing, albeit limited, genetic-geographic population substructure in the Dutch population based on genome-wide data and a lack of this for

mitochondrial SNP based data. Despite the aforementioned studies, Y-chromosomal SNP data from the Netherlands remain scarce and do not cover the territory of the Netherlands well enough to

allow a reliable investigation of genetic-geographic population substructure. Here we provide the first substantial dataset of detailed spatial Y-chromosomal haplogroup information in 2085

males collected across the Netherlands and supplemented with previously published data from northern Belgium. We found Y-chromosomal evidence for genetic–geographic population substructure,

and several Y-haplogroups demonstrating significant clinal frequency distributions in different directions. By means of prediction surface maps we could visualize (complex) distribution

patterns of individual Y-haplogroups in detail. These results highlight the value of a micro-geographic approach and are of great use for forensic and epidemiological investigations and our

understanding of the Dutch population history. Moreover, the previously noted absence of genetic-geographic population substructure in the Netherlands based on mitochondrial DNA in contrast

to our Y-chromosome results, hints at different population histories for women and men in the Netherlands. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SUBDIVIDING Y-CHROMOSOME HAPLOGROUP R1A1

REVEALS NORSE VIKING DISPERSAL LINEAGES IN BRITAIN Article Open access 02 November 2020 AUTOSOMAL GENETICS AND Y-CHROMOSOME HAPLOGROUP L1B-M317 REVEAL MOUNT LEBANON MARONITES AS A

PERSISTENTLY NON-EMIGRATING POPULATION Article 04 December 2020 CHARACTERIZATION OF Y CHROMOSOME DIVERSITY IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR: EVIDENCE FOR A STRUCTURED FOUNDING POPULATION Article

Open access 29 October 2024 INTRODUCTION An extensive database of genetic variation and detailed insight in genetic-geographic population substructure is essential for forensic

investigation, epidemiology and historical, archaeological, evolutionary and genealogy studies within a nation (see for example [1]). For the Netherlands there are several databases

available on autosomal data from which inferences have been made about Dutch population (sub)structure. The study by Lao et al. [2] on genome-wide autosomal single nucleotide polymorphism

(SNP) data demonstrated genetic-geographic population substructure and a clinal distribution of genomic diversity in southeast to northwest direction across the current territory of the

Netherlands. They concluded that these patterns must have a relatively recent origin, considering multiple recent events that could have influenced the Dutch population structure, such as

large-scale land reclamation projects starting in the High Middle Ages. Furthermore, Abdellaoui et al. [3], using an independent genome-wide dataset, observed population differentiation

along both a north–south and a west-east direction and identified a higher rate of homozygosity in the north compared with the south, which was explained by a serial founder effect as a

result of historical northward migrations. Similarly, also the study of The Genome of the Netherlands Consortium [4] on whole-genome sequencing data observed subtle genetic-geographic

substructure along a north–south gradient and also increased homozygosity in the north, for which they proposed the same explanation as Abdellaoui et al. [3]. In contrast to the autosomal

genome-wide data, a study on mitochondrial DNA on a subset of the above mentioned dataset studied by Lao et al. [2], could not detect significant genetic-geographic substructure in the

Netherlands [5]. Considering the non-recombining part of the Y-chromosome, Roewer et al. described a significant division between the north and the south of the Netherlands, based on

Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat (YSTR) haplotypes from 275 samples from five different locations, but this division was not detectable based on SNP data [6]. Moreover, studies on SNP based

Y-chromosome haplogroup (YHG) frequencies in the southern Netherlands and Belgium showed a significant difference between the Dutch and the Belgian samples based on haplogroup proportions

and gradients for YHGs R1b-M405, R1b-L48, and R1b-M529 [7,8,9]. Despite the aforementioned studies, YHG data from the Netherlands remain scarce and do not cover the territory of the

Netherlands well enough to allow a reliable investigation of genetic-geographic population substructure. Such a Dutch YHG database would be a valuable addition to the already available

autosomal and mitochondrial DNA information for various reasons. First of all, in contrast to the autosomes the Y-chromosome is uniparental. This means its genetic variation is influenced

by, but also indicative of, male-specific demographic processes and is therefore very useful in reconstructing population histories. Also, in the forensic world genome wide data analysis is

still scarcely applied (and standardized) and therefore uniparental markers remain essential for inferring bio-geographic ancestry of suspects or unidentified victims. Therefore, regional

knowledge on genetic-geographic substructure of the Y-chromosome is of great value. The phylogenetic resolution of the current YHG tree is now sufficiently high [10] to be able to detect

geographic patterns on a micro-regional scale [7]. In this context, the Netherlands can be considered a micro-region, covering only 33,687 km2 of land [11], although it is densely populated

with about 17 million inhabitants [12]. The goal of this study is to develop a database with Dutch YHG information and identify and quantify the possible presence of geographic patterns and

population substructure based on this data within the Netherlands. For some of our analyses, we also included data from the northern part of Belgium, including Flanders and the

Brussels-Capital region. This part of Belgium borders the south of the Netherlands and Dutch is (one of) the official language(s) there. This area covers 13,684 km2 of land [13, 14] and has

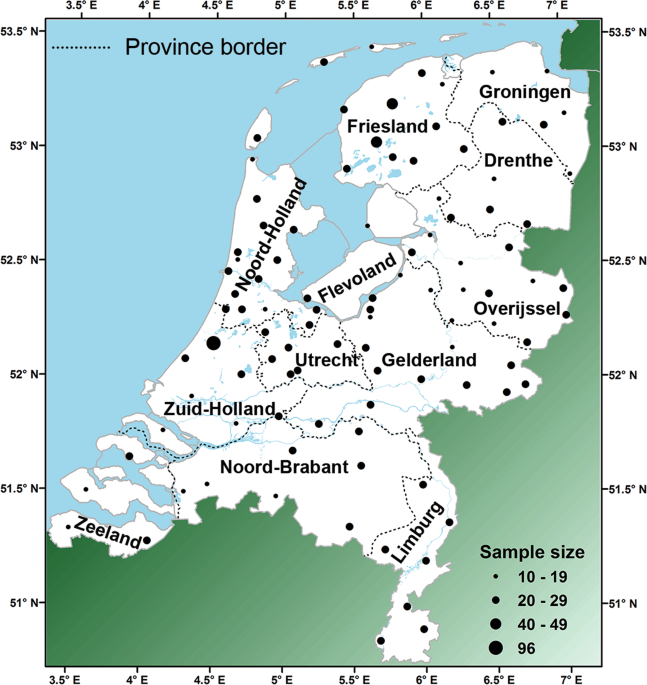

about 7.5 million inhabitants [15]. MATERIALS AND METHODS For our study, we used 2085 blood-donor samples from male donors that are reported to be unrelated and residing in a-priori selected

locations. This is the same dataset as published in Westen et al. for autosomal STR data [16] and Westen et al. for YSTR data [17]. Samples were received anonymously, with only the place of

residency of the donor indicated (see also Supplementary information). The number of samples per location varied from 1 to 96. Locations with less than ten samples were pooled with nearby

locations. This resulted in sample sizes varying between 10 and 96 (average = 21) from 99 locations covering the Dutch area in a grid-like scheme (Fig. 1 and Table S1). This dataset will

from here on be referred to as the “Dutch dataset”. Because of the sampling strategy, excluding several of the major cities that harbor large recent (since 1950) immigrant populations [18],

this dataset is to some extend biased in representing the full genetic diversity among the Dutch male population. DNA was isolated as described in Westen et al. [16]. A SNaPshot® Multiplex

System Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) assay was designed for a core set of 26 SNPs covering all the main YHGs (A-T) and four subgroups of YHG R (Fig. 2). Further subtyping of

samples assigned to YHGs E and R1b was done in additional multiplexes and for YHGs F(xG, H, I/ J, and K), J, and Q in monoplex (Fig. 2). In total, 92 Y-SNPs were analyzed allowing the

inference of 88 YHGs. Subgroups of YHG I-M170 were inferred with Whit Athey’s Haplogroup Predictor [19, 20], based on 16 YSTRs that were previously published for our dataset [17]. Because

sub-haplogroups of I-M170 were inferred from YSTR data, they were not considered for further analysis, other than proportion estimates, due to potential inference inaccuracies. For detailed

information on SNP design, sequencing, and haplogroup prediction see Supplementary information. To increase the study area and enhance the possibility to detect geographic patterns, a

dataset of 773 males from the northern Belgian provinces West-Vlaanderen, Oost-Vlaanderen, Antwerpen, Vlaams-Brabant, the Brussels region, and Limburg, using the actual living place at the

time of sample collection (the “present” dataset), as previously described by Larmuseau et al. [7], was incorporated in this study for part of the statistical analyses. This dataset will be

referred to as the “Flanders dataset” and the dataset consisting of both the Dutch and the Flanders dataset will be referred to as the “combined dataset”. Because there were some differences

between the SNP assays applied to the Dutch and Flanders datasets, YHGs were synchronized to a level that they were comparable for data analysis (consensus YHGs, Table S2). The samples from

the Flanders dataset were collected with a different sampling strategy than the Dutch dataset and mostly single samples are available per location. Therefore, several methods for detecting

population substructure and gradients were not applicable to the Flanders dataset. We used two different approaches in order to search for genetic-geographic patterns in the Dutch dataset.

First, classical multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was performed with R software version 3.4.4 [21] to represent in two dimensions a distance matrix based on Slatkin’s linearized _F_ST

on YHG proportions among sampling locations. This matrix was computed with ARLEQUIN software version 3.11 with standard settings [22]. The resemblance of the first two MDS dimensions with

the geographic sampling locations was quantified by means of a symmetric Procrustes rotation, as implemented in the protest method of the “vegan” R package [23]. Second, a correspondence

analysis on YHG proportions and sample locations was performed in R with the “ca” package. Outliers, if any, in the first two dimensions were removed on visual inspection. The first two

dimensions were compared with the geographic coordinates of the sampling locations with a symmetric Procrustes rotation. Both methods were only applied to the Dutch dataset. The above

mentioned previous study by Lao et al. [2] on genome-wide autosomal SNP data was based on a subset of the Dutch dataset as published here. This study found evidence for genetic-geographic

substructure in the Dutch population. To test for similarities between genetic-geographic substructure based on the genome-wide autosomal SNP data and YHG data we estimated the similarity

between the Slatkin’s linearized _F_ST genetic distance matrices between populations while controlling by geographic distance, by conducting a partial Mantel test with PASSaGE version 2

software [24]. Since the dataset of Lao et al. [2] is a subset of the Dutch dataset (917 samples from 46 locations), we applied the same selection on the YHG dataset (applying all selection

criteria as described in Lao et al. [2] and additionally excluding all locations with less than ten samples). To detect geographic patterns for individual YHGs, we applied two statistical

methods on (sub)YHGs with a proportion of ≥1% (corresponding to a minimum of 20 samples in the Dutch dataset). First, we computed Moran’s I spatial autocorrelograms with binary weight tests

for each YHG using PASSaGE version 2 software, with ten distance classes of equal width, assuming randomly distributed data and excluding the largest distance class. Statistical significance

(_p_-value < 0.05) of the spatial autocorrelogram of each YHG was estimated with 999 permutations and Bonferroni correction was applied. This test was only applied to the Dutch dataset.

Second, we estimated the linear relationship between the proportion of each YHG and geographic coordinates with a generalized linear model (GLM) using a binomial logit link in R with the

“vegan” package. Bonferroni correction was applied on the resulting _p_-values for the correlation (0.05/(number of tested YHGs (excluding R1b-M405 Total and R1b-S116 Total) +1 for not

tested haplogroups)). Gradients that are significant before Bonferroni correction, but no longer after, will be referred to as marginally significant. This test was applied to both the Dutch

and the combined dataset. To visualize spatial patterns, we created prediction surface maps for all YHGs with a proportion of ≥1% with the ordinary Kriging interpolation technique in ArcGIS

version 10.2 with the Spatial Analyst extension. Data were classified in equal intervals, unless the distribution of the data required otherwise. The number of classes was defined manually,

depending on the range of predicted values. This was only done for the Dutch dataset. Because YHGs R1b-M405 and R1b-S116 were often not or to a limited extend subtyped in previous

publications, we also provide collective information for these YHGs under the names of R1b-M405 Total (comprising M405, U198, L48, and L47) and R1b-S116 Total (comprising S116, U152, M529,

and M167). Data generated in this study have been uploaded to the public database YHRD under accession number YA002897 [25, 26]. RESULTS YHGs were manually assigned to all 2085 samples of

the Dutch dataset. In total, 32 different YHGs were observed. YHGs I (28%) and R (62%) are by far the most common. Within YHG R, subgroups R1b-L48 (15%), R1b-M405 (14%), and R1b-S116 (9%)

are the three most common ones (Table 1, Fig. 3). The combined dataset also mainly contains YHGs I (26%) and R (63%) (Table 2). The first two dimensions of the MDS analysis using a genetic

distance matrix between populations explained 4.8% and 2.8% of the total YHG proportion variance, respectively. There is a statistically significant, weak positive correlation between these

two dimensions and the geographical coordinates of the sampling locations as estimated by a Procrustes analysis (_r_ value = 0.37, _p_-value = 0.001 after 999 permutations) (Fig. 4a). The

first two dimensions of the correspondence analysis using a sample by YHG frequency contingency table explain 8.8% and 7.9% of the total variance, respectively. There is no statistically

significant correlation between these two dimensions and the geographical coordinates of the sampling locations with a Procrustes rotation (Fig. S1). Visual inspection of the correspondence

analysis plot, however, showed several putative outliers (the locations Harderwijk, Purmerend, Putten and Veghel) (Fig. S1). When these locations are excluded from the analysis, the first

two dimensions of the correspondence analysis explain 8.6% and 7.4% of the total variance. This time there is a statistically significant, weak positive correlation between these two

dimensions and the geographical coordinates of the sampling locations with a Procrustes rotation (_r_ value = 0.268, _p_-value = 0.002 after 999 permutations) (Fig. 4b). When comparing the

new YHG data with the previous genome-wide autosomal SNP data from Lao et al. [2], we did not observe a statistically significant correlation between the genetic distance matrices based on

Slatkin’s _F_ST between the two datasets after controlling by geographic distance (_r_ = 0.005, 2-tailed _p_-value partial Mantel test = 0.954 after 999 permutations). The spatial analyses

of individual YHGs identified departure from spatial randomness for several of them. The spatial autocorrelograms suggest statistically significant spatial trends compatible with a cline

[27] after Bonferroni correction for the following YHGs in the Dutch dataset: G-M201, I-M170, R1b-M405, R1b-S116 Total, and R1b-S116 (Table 3, Fig. S2). The GLM results for the Dutch dataset

also indicate (marginally) significant correlation with latitude and/or longitude for several YHGs, where G-M201, R1b-L23, R1b-S116 Total, R1b-S116, and R1b-U152 increase from north to

south, R1b-M405 Total and R1b-L48 increase from south to north, R1b-M405 increases from east to west and I-M170 increases from southwest to northeast (Table 3). In the combined dataset, the

GLM also indicates (marginally) significant correlation with latitude and/or longitude for several YHGs, where YHGs G-M201, J2-M172, R1b-M269, and R1b-S116 increase from north to south,

R1b-M405 Total and R1b-L48 increase from south to north, I-M170 increases from southwest to northeast and R1b-S116 Total, R1b-U152 and R1b-M529 increase from northeast to southwest (Table

4). From all the YHGs for which prediction surface maps were created, only YHG R1b-M529 is more or less evenly distributed over the Netherlands. All other YHGs show more distinct patterns of

distribution, either clinal or non-clinal and more patchy (Figs. 5 and S3). The prediction surface maps in general support the statistically (marginally) significant patterns found with the

spatial autocorrelograms and/or GLM analyses, but also allow for a more elaborate description of the pattern of distribution. In accordance to the spatial autocorrelogram and GLM result,

the prediction surface map of YHG G-M201 shows a southward increase in proportion, although the overall frequency is low. However, the observed pattern appeared more complex than just a

cline, best described as an inverse saddle pattern. The prediction surface map of YHG I-M170 is the only one for which we did not classify the frequency in equal intervals. Overall, the

range of frequency per location was very large compared with the other YHGs, running from 3% to 54%. There were, however, hardly any observations below 16% and above 36%. We therefore partly

applied classification by natural breaks, where the lowest classes, between 3% and 16% were pooled in one class and the highest classes, between 36% and 54%, were pooled in one class.

Between 16% and 36% we applied equal intervals. What stands out most for this map, in comparison to the others, are the distinct local higher or lower proportions compared with the

surrounding area, despite the clearly visible increase from southwest to northeast. What is striking about the distribution of YHG R1b-L23, is that the proportions are very low for the whole

country, apart from a limited number of local concentrations of somewhat higher proportions. Although proportions are slightly higher in the south, the map does not really support the

marginally significant southward gradient from the GLM model. The map for YHG R1b-M405 Total suggests a gradient from southeast to northwest, while with the GLM for R1b-405 Total only a

significant northward gradient was found. The map for YHG R1b-M405 shows a gradient that runs from the northeast to the southwest, while only a marginally significant westward gradient was

observed with the GLM. For YHG R1b-L48 the map suggests a gradient in a northwestern direction, rather than the significant northward gradient as indicated by the GLM results. For YHGs

R1b-S116 Total, R1b-S116, and R1b-U152, the maps show similar patterns and suggest more southeastwards gradients, rather than the southward gradients as suggested by the GLM results.

Furthermore, the prediction surface maps suggest the presence of other complex patterns that could not be identified with the statistical analyses we performed, or were not significant,

mostly due to low proportions. For YHG E1b-V13, we observe a depression-like pattern with highest proportions in the southwest and northeast and a band of lower proportions running from the

northwest to the southeast. YHG J2-M172 shows a complex pattern with dispersed patches of higher and lower proportions. For R1a-SRY10831 we see two distinct areas of higher concentrations in

the center and northeast of the country. YHG R1b-U198 seems to follow a depression-like pattern, somewhat similar to E1b-V13, with highest proportions in the southwest and northeast and a

band of lowest proportioning the center. We see a more or less random distribution for R1b-L47, except for a distinct vertical band of low proportions in the northern half of the country and

also rather distinct patches of high proportions in the northeast and center. Finally, the map for R1b-M167 indicates a clear concentration of low proportions in the southeast and

increasing proportions towards the northwest. DISCUSSION The Y-chromosomal genetic diversity present in the Dutch dataset showed clear spatial differentiation. What is remarkable,

considering the small size of the Netherlands, is that additionally we see a non-random spatial pattern, either by formal testing or visually in the prediction surface maps, for nearly every

YHG tested (≥1%). Roewer et al. already detected population substructure in the form of a division between two samples from the south of the Netherlands and three samples from the

central-west and north. This was based, however, on YSTR data and could not be replicated with YSNP data from a smaller selection of that same sample set [6]. The contrast between the

division they detected with the YSTR data and the more gradual patterns we observed here based on YSNP data are probably related to the relatively small sample set and geographically far

dispersed sample locations in Roewer et al., but may also be related to fundamental differences between YSTRs and YSNPs, such as mutation rate. The contrast between the lack of substructure

based on YSNP data in Roewer et al. and our results are probably related to the low resolution of YSNP typing (only those to assign to the most common European YHGs) and also the small

sample set in the study of Roewer et al. This also demonstrates the value of a substantial and geographically well distributed dataset with detailed YSNP information. The population

substructure and gradients for many of the individual YHGs we found in our study are in strong contrast with the apparent lack of genetic-geographic patterns for mtDNA data, as previously

reported for a subset of the same sample set we used for our study [5]. This could be an indication of different demographic histories for women and men. One could think, for example, of the

patrilocal residence system, which is typical for farming societies, such as the Dutch [28]. In these societies sons stay with their family and daughters move to the residence of their

husbands. Also, genetic drift may have acted differently on mt-DNA than on Y-chromosomes. The dissimilarity between the geographic-genetic patterns we observed for the Y-chromosome and the

one found for genome-wide autosomal SNP data by Lao et al. [2], based on a selection of our dataset, can first of all most likely be attributed to genetic drift acting differently on

autosomal DNA than on uniparental markers such as the Y-chromosome. Besides that, the autosomal genetic variation and distribution are affected by both female and male populations and

therefore the gradients we observed for the male population by means of the YHG data will be diluted by the lack of gradients for the female population by means of the mtSNP data. A solid

explanation, however, for the differences in the geographic-genetic patterns between autosomal, mitochondrial, and Y-chromosomal SNP data requires additional data from past periods by means

of ancient DNA and multidisciplinary research, including historians and archaeologists. Larmuseau et al. already hinted at the value of temporal analyses with several studies where they

reconstructed historical patterns based on a combination of present-day samples and genealogical data and found strong indications for temporal fluctuations of YHG proportions [7, 8]. When

we additionally include the Flanders dataset in our analyses, we detect almost the same gradients with formal testing. This is not surprising since all but one of the significant gradients

we observed in the Dutch dataset run in a (more or less) longitudinal direction and the inclusion of the Flanders dataset extends the territory mostly southwards. However, two exceptions

concern YHGs R1b-M405 and R1b-M529. For R1b-M405, we detected a marginally significant westward gradient in the Dutch dataset, but no significant gradient in the combined dataset. This is a

remarkable observation, since it is one of the three main subgroups in both the Dutch and Flanders datasets. For R1b-M529 we did not detect a significant gradient in the Dutch dataset, while

we do detect a (marginally) significant south(west)ward gradient in the combined dataset. All together our results are in line with the findings of Larmuseau et al. [8] of significant

population differentiation between the provinces of the historical region of the Duchy of Brabant, currently covering the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant and the Belgian provinces of

Antwerpen, Brussel, Vlaams Brabant, and Waals Brabant. This was interpreted as the result of isolation by distance, rather than a distinct difference between the present-day Dutch and

Belgians. Considering the many north–south clines we observed we can support this assumption. There are two other comparable examples of YSNP based population studies in the vicinity of the

Netherlands; one for Germany and Poland by Kayser et al. [29] and one for France by Ramos-Luis et al. [30], although both subtyped to a considerably lower resolution than we did. Kayser et

al. detected a significant west to east gradient for YHG R1a1 and a reverse gradient for YHG R1(xR1a1) across Germany and Poland. Within Germany, they found Y-chromosome differentiation

between Western Germany and Eastern Germany, which the authors explained by more ancient events such as stronger Slavic influence on eastern than on western parts of Germany. In our study we

did not subtype further than R1a, but this YHG is not very common in our dataset (4%) and shows no gradient. Overall though, it’s frequency fits the eastward increasing gradient as

detected by Kayser et al. Since R1(xR1a1) was not further subtyped and we detected contradictory gradients within R1b, it is not possible to compare patterns. In the French study by

Ramos-Louis et al. on samples from seven regions they reported no clear indications for population substructure, other than Bretagne being a genetic outlier [30]. This in itself is

remarkable for such a large country. Considering their resolution of SNP typing we could compare their data with our significant gradients for YHGs G, I, and R1b-M405 Total, but in neither

case do we see evidence for the continuation of the gradients we observed. To further put our results in a broader context, we compare the (marginally) significant YHG gradients in the Dutch

dataset with published geographic distribution patterns in Europe. According to Rootsi et al. [31] YHG G-M201 is relatively rare in Europe, with average proportions below 5% in northwestern

Europe, which is consistent with our findings. Because proportions are low throughout the most of Europe, there is no clear gradient, but overall it increases from northwest to southeast,

similar to the gradient observed in the Dutch dataset with the GLM and prediction surface map. The geographical distribution of YHG I-M170 in Europe, on the other hand, is more complex, with

two centers of high concentrations: one in Scandinavia and one in southern Europe around the Dinaric Alps [32]. In northwest Europe, though, it shows an increase from southwest to

northeast, which is similar to the trend we observed in the Dutch dataset. YHG R1b-L23 was studied in Myres et al. [33], but since this YHG is so rare in Western Europe, as we also see in

the Dutch dataset, genetic-geographic patterns are absent for Europe. For R1b-M405 and R1b-L48 no other European-wide data are available, and we are therefore limited to compare just

R1b-M405 Total. In both Myres et al. [33] and Busby et al. [34] R1b-M405 Total is depicted with a more or less concentric distribution, with the Netherlands as the center. It is therefore

difficult to compare the European trend with the Dutch one, which increases from southeast to northwest, although statistically only the north–south cline is significant. The proportions

that they observed are similar to our observations, however. According to Myres et al. R1b-S116 shows a southwestern to northeastern decrease in Europe, while in the Dutch dataset the

gradient is directed from northwest to southeast. Average proportions are more or less similar though [33]. R1b-U152 has relatively high proportions in central–southern Europe and lower

proportions on the peripheral areas. The gradient and proportions as observed in the Dutch dataset are similar to those described in Myres et al. [33]. The (marginally) significant trends

that are observed in our study in the Dutch dataset in most cases seem to more or less follow the European-wide trends for YHG distributions. The fact that our results resemble these

European trends could be interpreted as the result of European-wide events. However, recent studies on both modern [35, 36] and ancient populations [37,38,39,40] indicate the importance of

including data from past populations when trying to explain the present picture. Others also argue that local, but also more recent, demographic events may have had just as much or even more

influence on the distribution of current genetic variation and produce similar patterns as major events in prehistory [41,42,43]. In summary, our detailed analysis of YHG distribution in

the Netherlands, based on 2085 geographically dispersed males resulted in an informative database. By combining several statistical methods, we have been able to detect Y-chromosome based

genetic-geographic population substructure and significant gradients for several individual YHGs in the Netherlands, some of which extend to the south into the northern part of Belgium and

eastward into Germany. These observations indicate the value of subtyping YHGs to a highly detailed level in micro geographic regions and add to the existing knowledge based on genome-wide

data and mitochondrial data. It is therefore of great use as a reference in forensic casework in the Netherlands in relation to genetic ancestry and geographic origin assessments of suspects

or unidentified victims. Moreover, the geographic patterns we observed, in addition to genome wide data, stress the importance of taking geographic origin into account in sampling

strategies for control groups and comparing data from subpopulations in epidemiological studies. The discrepancies between patterns of population substructure of mitochondrial and

Y-chromosomal DNA data point to different population histories for women and men in the Netherlands. However, solid explanations for the observed spatial patterns require further

multidisciplinary research, including historians and archaeologists and detailed YHG data, similar to what we present here, from past Dutch populations via ancient DNA analysis. CHANGE

HISTORY * _ 23 OCTOBER 2019 A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0528-9 _ REFERENCES * Larmuseau MH, Boon N, Vanderheyden N, Van Geystelen A,

Larmuseau HF, Matthys K, et al. High Y-chromosomal diversity and low relatedness between paternal lineages on a communal scale in the Western European Low Countries during the surname

establishment. Hered (Edinb). 2015;115:3–12. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lao O, Altena E, Becker C, Brauer S, Kraaijenbrink T, van Oven M, et al. Clinal distribution of human genomic

diversity across the Netherlands despite archaeological evidence for genetic discontinuities in Dutch population history. Invest Genet. 2013;4:9. Article Google Scholar * Abdellaoui A,

Hottenga JJ, de Knijff P, Nivard MG, Xiao X, Scheet P, et al. Population structure, migration, and diversifying selection in the Netherlands. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:1277–85. Article CAS

Google Scholar * The Genome of the Netherlands Consortium. Whole-genome sequence variation, population structure and demographic history of the Dutch population. Nat Genet. 2014;46:818. *

Chaitanya L, van Oven M, Brauer S, Zimmermann B, Huber G, Xavier C, et al. High-quality mtDNA control region sequences from 680 individuals sampled across the Netherlands to establish a

national forensic mtDNA reference database. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2016;21:158–67. Article CAS Google Scholar * Roewer L, Croucher PJ, Willuweit S, Lu TT, Kayser M, Lessig R, et al.

Signature of recent historical events in the European Y-chromosomal STR haplotype distribution. Hum Genet. 2005;116:279–91. Article CAS Google Scholar * Larmuseau MH, Vanderheyden N, Van

Geystelen A, van Oven M, Kayser M, Decorte R. Increasing phylogenetic resolution still informative for Y chromosomal studies on West-European populations. Forensic Sci Int Genet.

2014;9:179–85. Article CAS Google Scholar * Larmuseau MH, Ottoni C, Raeymaekers JA, Vanderheyden N, Larmuseau HF, Decorte R. Temporal differentiation across a West-European Y-chromosomal

cline: genealogy as a tool in human population genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:434–40. Article CAS Google Scholar * Larmuseau MH, Vanderheyden N, Jacobs M, Coomans M, Larno L, Decorte

R. Micro-geographic distribution of Y-chromosomal variation in the central-western European region Brabant. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2011;5:95–9. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hallast P,

Batini C, Zadik D, Maisano Delser P, Wetton JH, Arroyo-Pardo E, et al. The Y-chromosome tree bursts into leaf: 13,000 high-confidence SNPs covering the majority of known clades. Mol Biol

Evol 2015;32:661–73. Article CAS Google Scholar *

http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=70262NED&D1=0-1,5,11,18,24,27,31,41&D2=0,5-16&D3=a&HD=130529-1417&HDR=G2&STB=G1,T *

https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/37296ned/table?ts=1544118080903 * https://www.vlaanderen.be/nl/ontdek-vlaanderen *

http://bisa.brussels/cijfers/kerncijfers-van-het-gewest#.XAljAflKhaQ * http://www.ibz.rrn.fgov.be/fileadmin/user_upload/fr/pop/statistiques/population-bevolking-20180101.pdf * Westen AA,

Kraaijenbrink T, Robles de Medina EA, Harteveld J, Willemse P, Zuniga SB, et al. Comparing six commercial autosomal STR kits in a large Dutch population sample. Forensic Sci Int Genet.

2014;10:55–63. Article CAS Google Scholar * Westen AA, Kraaijenbrink T, Clarisse L, Grol LJ, Willemse P, Zuniga SB, et al. Analysis of 36 Y-STR marker units including a concordance study

among 2085 Dutch males. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2015;14:174–81. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lucassen L, Feldman D, Oltmer J (eds). Paths of integration. Migrants in Western Europe

(1880–2004). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2006. * Athey TW. Haplogroup prediction from Y-STR values using an allele frequency approach. J Genet Geneal. 2005;1:1–7. Google Scholar

* Athey TW. Haplogroup prediction from Y-STR values using a Bayesian-Allele frequency approach. J Genet Geneal. 2006;2:34–39. Google Scholar * R Core Team. R: A language and environment for

statistical computing. Vienna: R foundation for statistical computing; 2013. Google Scholar * Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.0: An integrated software package for

population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. Article CAS Google Scholar * Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McLinn D, et al. vegan:

Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4-3. * Rosenberg MS, Anderson CD. PASSaGE: pattern analysis, spatial statistics and geographic exegesis. Version 2. Methods Ecol Evol.

2011;2:229–32. Article Google Scholar * Willuweit S, Roewer L. The new Y chromosome haplotype reference database. Forensic Sci Int: Genet. 2015;15:43–48. Article CAS Google Scholar *

https://yhrd.org/ * Barbujani G. Geographic patterns: how to identify them and why. Hum Biol. 2000;72:133–53. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Seielstad MT, Minch E, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Genetic

evidence for a higher female migration rate in humans. Nat Genet. 1998;20:278. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kayser M, Lao O, Anslinger K, Augustin C, Bargel G, Edelmann J, et al.

Significant genetic differentiation between Poland and Germany follows present-day political borders, as revealed by Y-chromosome analysis. Hum Genet. 2005;117:428–43. Article Google

Scholar * Ramos-Luis E, Blanco-Verea A, Brión M, Van Huffel V, Sánchez-Diz P, Carracedo A. Y-chromosomal DNA analysis in French male lineages. Forensic Sci Int: Genet. 2014;9:162–68.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Rootsi S, Myres NM, Lin AA, Jarve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, et al. Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and

the Caucasus. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:1275–82. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rootsi S, Magri C, Kivisild T, Benuzzi G, Help H, Bermisheva M, et al. Phylogeography of Y-chromosome

haplogroup I reveals distinct domains of prehistoric gene flow in Europe. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:128–37. Article CAS Google Scholar * Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Jarve M, King RJ, Kutuev

I, et al. A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:95–101. Article Google Scholar * Busby GB, Brisighelli F,

Sanchez-Diz P, Ramos-Luis E, Martinez-Cadenas C, Thomas MG, et al. The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:884–92. PubMed

Google Scholar * Hellenthal G, Busby GB, Band G, Wilson JF, Capelli C, Falush D, et al. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science. 2014;343:747–51. Article CAS Google Scholar *

Batini C, Hallast P, Zadik D, Delser PM, Benazzo A, Ghirotto S, et al. Large-scale recent expansion of European patrilineages shown by population resequencing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7152.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe.

Nature. 2015;522:207–11. Article CAS Google Scholar * Allentoft ME, Sikora M, Sjogren KG, Rasmussen S, Rasmussen M, Stenderup J, et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature.

2015;522:167–72. Article CAS Google Scholar * Olalde I, Brace S, Allentoft ME, Armit I, Kristiansen K, Booth T, et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest

Europe. Nature. 2018;555:190–96. Article CAS Google Scholar * Mathieson I, Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, Posth C, Szecsenyi-Nagy A, Rohland N, Mallick S, et al. The genomic history of

southeastern Europe. Nature. 2018;555:197–203. Article CAS Google Scholar * Barbujani G, Bertorelle G. Genetics and the population history of Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:22–5.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Jobling MA. The impact of recent events on human genetic diversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:793–9. Article CAS Google Scholar *

Pinhasi R, Thomas MG, Hofreiter M, Currat M, Burger J. The genetic history of Europeans. Trends Genet. 2012;28:496–505. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from The Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research within the framework of the Forensic Genomics Consortium

Netherlands. MHDL acknowledged a postdoctoral fellowship from the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO Vlaanderen; grant no. 1503216N). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Kristiaan J. van der

Gaag Present address: Department of Human Biological Traces, Netherlands Forensic Institute, The Hague, The Netherlands * Oscar Lao Present address: CNAG-CRG, Centre for Genomic Regulation

(CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Barcelona, Spain AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Human Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands

Eveline Altena, Risha Smeding, Kristiaan J. van der Gaag, Thirsa Kraaijenbrink & Peter de Knijff * Forensic Biomedical Sciences, Department of Imaging & Pathology, KU Leuven, Leuven,

Belgium Maarten H. D. Larmuseau & Ronny Decorte * Laboratory of Socioecology and Social Evolution, Department of Biology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Maarten H. D. Larmuseau * Histories

vzw, Mechelen, Belgium Maarten H. D. Larmuseau * Laboratory of Forensic Genetics and Molecular Archaeology, UZ Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Ronny Decorte * Department of Genetic Identification,

Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Oscar Lao & Manfred Kayser * Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Oscar Lao Authors * Eveline Altena View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Risha Smeding View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Kristiaan J. van der Gaag View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maarten H. D. Larmuseau View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ronny Decorte View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Oscar Lao View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Manfred Kayser View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thirsa Kraaijenbrink View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Peter de Knijff View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Peter de Knijff. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer

Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S4 RIGHTS

AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in

any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Altena, E.,

Smeding, R., van der Gaag, K.J. _et al._ The Dutch Y-chromosomal landscape. _Eur J Hum Genet_ 28, 287–299 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0496-0 Download citation * Received: 19

February 2019 * Revised: 09 July 2019 * Accepted: 02 August 2019 * Published: 05 September 2019 * Issue Date: 02 March 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0496-0 SHARE THIS

ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative