Relating plaque morphology to respiratory syncytial virus subgroup, viral load, and disease severity in children

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Viral culture plaque morphology in human cell lines are markers for growth capability and cytopathic effect, and have been used to assess viral fitness and select

preattenuation candidates for live viral vaccines. We classified respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) plaque morphology and analyzed the relationship between plaque morphology as compared to

subgroup, viral load and clinical severity of infection in infants and children. METHODS: We obtained respiratory secretions from 149 RSV-infected children. Plaque morphology and viral load

was assessed within the first culture passage in HEp-2 cells. Viral load was measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as was RSV subgroup. Disease severity was determined by

hospitalization, length of stay, intensive care requirement, and respiratory failure. RESULTS: Plaque morphology varied between individual subjects; however, similar results were observed

among viruses collected from upper and lower respiratory tracts of the same subject. Significant differences in plaque morphology were observed between RSV subgroups. No correlations were

found among plaque morphology and viral load. Plaque morphology did not correlate with disease severity. CONCLUSION: Plaque morphology measures parameters that are viral-specific and

independent of the human host. Morphologies vary between patients and are related to RSV subgroup. In HEp-2 cells, RSV plaque morphology appears unrelated to disease severity in RSV-infected

children. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DETECTION OF RESPIRATORY SYNCYTIAL VIRUS DEFECTIVE GENOMES IN NASAL SECRETIONS IS ASSOCIATED WITH DISTINCT CLINICAL OUTCOMES Article 01

April 2021 SARS-COV-2 ANTIGENEMIA AND RNAEMIA IN ASSOCIATION WITH DISEASE SEVERITY IN PATIENTS WITH COVID-19 Article Open access 28 June 2024 DIFFERENCES IN CLINICAL SEVERITY OF RESPIRATORY

VIRAL INFECTIONS IN HOSPITALIZED CHILDREN Article Open access 04 March 2021 MAIN Disease severity in infants with a primary respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection varies dramatically,

with most infants not requiring hospitalization. In others, the infection produces much more severe disease, and can result in hospitalization, supplemental oxygen requirement, respiratory

failure, and even death. Although host factors, including the presence of pre-existing lung or heart disease, prematurity, and maternal-derived pre-existing humoral neutralizing antibody

concentrations, account for some of these differences, they are not sufficient to fully explain the range of disease severity. Host genetic factors also account for some of these severity

differences (1,2), but studies in identical twins have calculated that genetic factors explain only 16% of these differences (3). Viral-specific factors as causes of significant clinical

disease severity differences have been identified in many other viral infections (4,5,6). Viral load has been clearly identified as a major risk factor in disease severity, but it represents

a complex dynamic between host immune responses and intrinsic viral characteristics. RSV subgroup A has been shown to be associated with slightly greater disease severity than RSV subgroup

B in several studies (7,8), but in others, such a difference was not evident (9,10). Certain regions of the RSV-G (secretory or membrane-bound) protein are proinflammatory and mimic the

human CXC3 chemokine. One study sequencing the G gene suggested a relationship with RSV disease severity (11). Intrinsic viral properties are responsible for growth characteristics _in

vitro_, such as plaque morphology. Viruses that form small plaques have traditionally been chosen as preattenuation subgroups from which to develop attenuated live viral vaccines. However,

for RSV, no clinical rationale exists for this selection practice. We therefore evaluated the relationship between classifications of plaque morphology as compared to subgroup, viral load

and clinical severity of infection in infants and children. RESULTS RSV plaque formation begins with a single infectious focus. This infection expands outward to form a visible plaque. HEp-2

cells are nonpolarized cells, continuously multiplying throughout the duration of the 5-d plaque assay culture. Within the HEp-2 cell plaque assay system, RSV infection spreads in two ways:

(i) directly from cell-to-cell via the fusion of adjacent cells’ plasma membranes forming visible syncytia, and (ii) through the elaboration of free virus, the diffusion of which is limited

within the plaque assay to only the neighboring cells because of the high viscosity of the methylcellulose overlay. PATIENT POPULATION Plaque morphology was evaluated on 149 enrolled

subjects who were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive for RSV. The characteristics of these subjects are described in TABLE 1 . The enrolled population was a previously healthy group of

children who, given the predictable seasonality of RSV, were likely to be experiencing their first RSV infection. As per the exclusion criteria, they had no known hemodynamically

significant congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, or known immune deficiency. The duration of symptoms prior to specimen collection for culture and plaque morphology assessment was

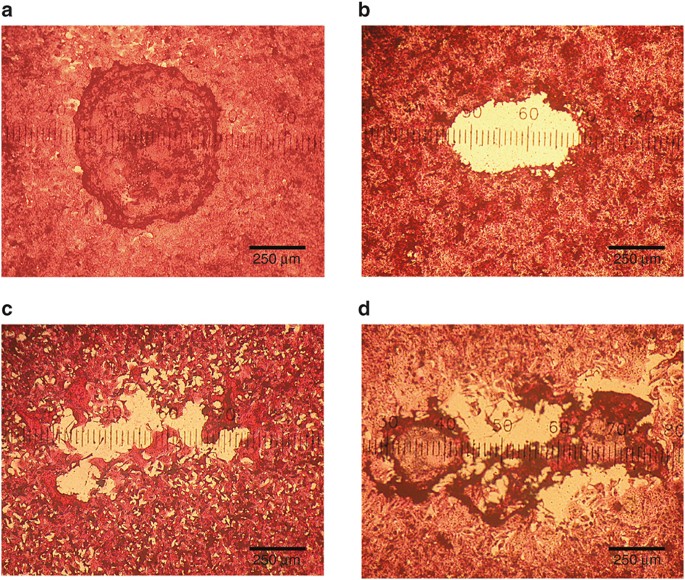

4.8 ± 2.4 d (mean ± SD), placing the time of virus collection early in the course of infection and around the time of peak viral load (12,13). DIVERSITY OF PLAQUE MORPHOLOGY There was a

great amount of diversity in plaque morphology in the primary HEp-2 cell plaque assays ( FIGURE 1 ). After observing over 100 plates, we developed a system to categorize plaque morphology in

the hematoxylin and eosin stained monolayers. If the virus-infected monolayer in the central portion of the plaque remained, it was defined as capped, whereas if the central portion did not

remain, it was defined as uncapped. Plaques with well-defined borders were described as sharp, while plaques with undefined, finger-like, or pseudopodic borders were categorized as not

sharp. One hundred and forty-one samples were culture-positive with sufficient growth to quantify by culture. Of these, 14 samples had a viral quantity which produced plaques too numerous to

individually count. The viral loads for these samples were set at the upper level of quantification (6.78 log plaque forming unit (PFU)/ml). Because of the density of these plaques, they

also could not be sized accurately. Thus, a different number of patients were evaluated for plaque morphology and viral load comparisons ( TABLE 2 ). The mean plaque size (diameter) of each

patient’s isolate varied substantially (range 265.2–975 μm). The percentage of capped plaques between patients also varied substantially (range 1–100%). Plaques were observed to be either

sharp or not sharp, with 70.5% of patient isolates forming plaques with not sharp characteristics ( FIGURE 1 , TABLE 2 ). RELATIONSHIP AMONG PATIENT’S VIRAL PLAQUE CHARACTERISTICS Certain

plaque characteristics were statistically associated with certain RSV subgroups. RSV subgroups were categorized as RSV-A or -B based on N-gene conserved sequences (14). RSV-A plaques were

significantly larger ( FIGURE 2A ) and less likely to be capped ( FIGURE 2B ) compared to those produced by RSV-B. Both viral load by PCR ( FIGURE 2C ) and by quantitative culture

(infectious virus) ( FIGURE 2D ) were greater in patients with RSV-A ( FIGURE 2C , D ). Whether or not a patient’s plaques were sharp or not did not vary by RSV subgroup ( FIGURE 2E ). The

plaque size did not appear to correlate with RSV load, as assessed either by PCR ( FIGURE 3A – C ) or by quantitative culture (infectious virus) ( FIGURE 3D – F ). As the plaque size

increased, the percentage of capped plaques within a patient’s culture significantly decreased ( FIGURE 3G , H ). The percentage of capped plaques was not significantly correlated with the

patient’s RSV load ( FIGURE 3J – O ). The sharpness of each patient’s isolate did not vary by viral load ( FIGURE 4A , B ) but it was correlated with plaque morphology characteristics (

FIGURE 4C , D ). PLAQUE MORPHOLOGIES AND CLINICAL DISEASE Subjects were classified into different degrees of disease severity. There were no observed associations between plaque morphology

and the severity of the patient’s disease ( FIGURES 5 and 6 ). PLAQUE CHARACTERISTICS FROM UPPER AND LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACTS Although there was marked diversity of plaque size and plaque

morphology among the isolates of different patients, there was a striking similarity of plaque size and morphology within the same patient on different days (data not shown) and within the

same patient on the same day but collected from the upper vs. the lower respiratory tract ( FIGURE 7 ). There were seven patients for whom there was access to their lower respiratory tracts

at enrollment. For these patients, the plaque characteristics were compared between their upper respiratory tract (nasal wash) and lower respiratory tract (deep tracheal aspirate) samples.

The sharpness, percentage of capped plaques, and plaque sizes were similar from these two anatomic sites ( FIGURE 7 ). The morphology of plaques from tracheal aspirates and nasal washes from

the same individual at the same evaluation time point were not sharp in both samples for four patients, and sharp in both for two patients. One patient showed different plaque types between

upper and lower respiratory tracts. The plaques displayed a sharp in the tracheal sample and a not sharp in the nasal wash sample. We only evaluated five paired nasal wash and tracheal

aspirate samples because one nasal wash from one subject and one tracheal aspirate from the other subject produced plaques that were so numerous that they overlapped each other on the plate

and did not allow accurate classification. DISCUSSION Viral growth characteristics in cell culture, including plaque morphology, have been related to pathogenesis and disease severity for

several human pathogens. It was shown that small plaque variants are related to virulence, propagation, and disease severity in multiple viruses. With herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1), a small

plaque phenotype associated with neuroinvasive disease, was isolated from the central nervous system of a severely affected infant (15,16). Subsequent passage of this small plaque phenotype

virus produced larger plaques that lost their _in vivo_ neuroinvasive properties (17). The neuroinvasiveness was suggested to be the result of lower efficiency of viral glycoprotein

processing. In West Nile virus, a small plaque phenotype showed less efficiency of replication in _in vitro_ culture compared to wild type (18), and it was attenuated in neuroinvasiveness

(19). Chemically produced mutants of dengue virus type 4 and tick-borne encephalitis virus display characteristics of small plaque morphology, temperature sensitivity, and attenuated

pathogenicity (20,21). Neuroblastoma cell-adapted yellow fever 17D virus also presents a small plaque phenotype, defective in cell penetration and attenuated growth efficiency (22,23,24).

Plaque size has also been shown to differ among different strains of the influenza A H1N1 subtype. These plaque sizes have been linked _via_ mathematical models to fundamental differences in

key parameters, which characterize the virus replication fitness of these different strains (25). Viral load drives human RSV disease severity (12,13,26,27). But, viral load is a complex

interplay among viral-specific factors and the dynamic host factors of innate immunity and cognate immune responses. Studying the role of viral-specific factors is challenging for RSV

because it cannot be reliably cultured after a single freeze-thaw cycle. Also, because RSV is an RNA virus, its mutation rate is rapid even within a single patient (28). Plaque size from

clinical isolates was shown in other viruses to change significantly even over the first several passages in tissue culture (17,29). Therefore, when studying viral-specific factors,

low-passage clinical isolates need to be utilized. Plaque morphology differences within a single uniform cell line are products of viral-specific factors. In the present study, the plaque

assays from the evaluated patients were performed on fresh respiratory samples under identical conditions (12,14). Since plaques were evaluated in dilute respiratory secretions, (generally

100- to 1,000-fold dilutions) and not within an undiluted sample, any putative host effect existing within the secretions was greatly diluted and likely not to affect plaque morphology.

Thus, the morphology of the plaque at a time point after inoculation represents an intrinsic viral-specific factor related to growth kinetics within that particular uniform cell line

(12,14). Here, we evaluate viral-specific characteristics within the first culture passage of multiple RSV clinical isolates. We chose to study these viral-specific factors as early as

possible in the course of disease in a population of infants who are likely to be experiencing their first RSV infection and who are immunologically naïve to the virus. Furthermore, we

selected a population that was as homogeneous as possible, so we could detect viral-specific differences unencumbered by differences in disease severity that might be determined more by the

underlying comorbidities of the host. We show for the first time that plaque size and morphology differ dramatically between infected individuals, but that within the same individual, these

viral-specific factors appear conserved ( FIGURE 7 ). These differences appear to be related to viral group, but even within RSV-A and RSV-B isolates, major differences in size and

morphology were clearly observed ( FIGURES 2A , B , E and 3 ). RSV-A has been shown in multiple studies to cause more severe disease than does RSV-B. A recent multicenter large survey of

children confirms this disease severity association (30). We have previously shown that viral load is higher in infants infected with RSV-A compared to RSV-B ( FIGURE 2C , D ) (14). Our

results suggest that intrinsic viral growth characteristics, not just host response factors, play a role in the viral load differences observed in infected patients. RSV-A produced

significantly larger plaques than RSV-B. In addition to plaque size differences, the RSV-A plaques shed their caps more frequently than RSV-B plaques ( FIGURE 2B ). The fact that the

infected cells within the monolayer were affected differently in infections with RSV-A compared to RSV-B suggests that there may be differences in the cytopathologic potential of these two

RSV subgroups in addition to intrinsic viral replication parameters. Whole viral genome sequencing has yet to be performed in large-scale clinical studies of RSV infection. However, it

appears that intrinsic viral growth kinetic properties and/or cytopathogenic properties may in part drive human RSV disease severity. Plaque size has been used to preselect certain viral

subgroups as low virulence candidates for further attenuation. The lack of correlation between plaque size and disease severity suggests that this assumption could be incorrect. HEp-2 cells

are different from respiratory epithelial cells, which are the primary infected target cells in human RSV infection. As opposed to the epithelial cells of the human respiratory tract, HEp-2

cells are not polarized, and do not reach static growth rates in tissue culture. In natural human RSV infection, the virus is released preferentially from the apical surface of polarized

respiratory epithelial cells. Because of these cellular differences, clinical RSV strains are likely to show different first-passage growth characteristics in HEp-2 cells compared to the

human respiratory epithelial cells in which they were adapted for rapid growth. This limitation may explain why we did not observe a correlation between plaque size or morphology and disease

severity ( FIGURES 5 and 6 ). The temperature of the human nose is significantly lower (32 °C) than the core body temperature (37 °C) in the lower respiratory tract (31). This temperature

difference and the relative viral-replicative fitness at these different temperatures has been leveraged in previous experimental live RSV vaccines (32,33,34,35) and in the licensed live

attenuated influenza vaccine (36). We compared the plaque morphology of the RSV isolated from selected patients’ upper respiratory tract with that collected at the same time from their lower

respiratory tract ( FIGURE 7 ). After culturing them at the same temperature and in identical conditions, the plaque characteristics these two anatomic sites were remarkably similar. In

conclusion, viral-specific factors related to growth characteristics are similar within individual RSV-infected patients, but are remarkably different among patients. These RSV-specific

growth characteristics may point to viral factors, which may explain differences in disease severity. Further studies of whole viral genome sequencing from clinical specimens and relating

these sequences to observed viral properties and clinical disease severity should be encouraged. METHODS STUDY SUBJECTS Study subjects were less than 2 y of age (_n_ = 149) and had acute

onset of respiratory infection that tested positive for RSV by PCR. Respiratory secretions collected on the first day of enrollment were utilized for plaque descriptions. Subjects were born

at term and were previously healthy. Patients with chronic lung disease, hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, immunodeficiency, RSV prophylactic treatment, or any steroid

use were excluded. This study was conducted with the approval of the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board, included appropriate informed consent, and complied with all relevant

guidelines and institutional policies. Nasal washes were performed as previously described (14). Seven of these study subjects had an endotracheal tube in place, therefore providing access

to the lower respiratory tract. In these subjects, both a nasal wash and tracheal aspirates were collected at the same times on the first day of enrollment, and on subsequent days. All

secretions were collected directly into 4 °C sucrose-containing RSV transport media and used for plaque assays within 3 h. Other individual aliquots of each respiratory secretion sample were

quickly frozen on dry ice and maintained at −80 °C until thawed for use in quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRTrtPCR) assays (37). Multiplexed PCR detection of respiratory

viruses other than RSV was not performed. However, viruses known to be associated with RSV codetections (rhinoviruses, adenoviruses, hMPV, and coronaviruses) do not grow or do not produce

visible plaques in our HEp-2 cell culture system. RSV CULTURE Plaque assays were performed as previously described (14) using the human RSV-A, Long strain ATCC VR-26 as a quantitative

standard. Briefly, four 10-fold dilutions (ranging from undiluted to 1:1,000) of fresh respiratory secretions were prepared and placed in triplicate in 12-well culture plates containing 80%

confluent HEp-2 cells. Secretions were incubated for 1 h and then overlayed with 1 ml of prewarmed 0.75% methylcellulose-containing growth media without rinsing the initial inoculum. Plates

were incubated for 5 d at 37 °C (5% CO2) and then formalin fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for plaque counting and morphology observation. The quantitative culture’s minimum and

maximum quantifiable RSV concentration was 0.48–6.78 log PFU/ml. PLAQUE MORPHOLOGY Plaque morphology was determined by investigators who were masked with respect to the patient’s clinical

outcome, RSV subgroup, viral load, and anatomic sites of sample acquisition. _Plaque size._ For each plate, five individual plaques representative of the viral population (not touching edges

of the well) were measured at 40× magnification. The longest vertical and horizontal axis for each plaque was averaged and converted to micrometers using the standard ocular division

calculation for the microscope and magnification. _Sharpness._ Some interplaque variability was present within a single patient’s viral isolate. Therefore, for each patient’s entire plaque

population, the majority of viral plaques were described as either being sharp or not sharp. Plaques with well-defined borders were described as sharp, while plaques with undefined,

finger-like borders were categorized as not sharp. Standard representative plates containing sharp plaques and not sharp plaques were reviewed by the investigators after every ten study

plates were viewed ( FIGURE 1 ). _Capping._ If the virus-infected HEp-2 cell monolayer of the central portion of the plaque remained, this was called capped, whereas if the central portion

did not remain, it was categorized as uncapped ( FIGURE 1 ). For each patient sample, 50–100 plaques were counted per well at 40× magnification, and the percentage of completely formed caps

was calculated. DISEASE SEVERITY PARAMETERS USED Because of their clinical relevance, hospitalization, duration of hospital stay, requirement for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) management, and

respiratory failure (requiring intubation) were used as disease severity indicators. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analysis was performed using standard techniques. D’Agostino and Pearson

omnibus normality tests were performed to determine the nature of the data distribution. For normally distributed data, the _t_-test was used. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney _U_-test was

used for data that were not normally distributed. All tests were two-tailed with the level of significance set at 0.05. For consistency of visualization, lines on the scattergrams represent

means and standard error margins regardless of the statistical test used for comparison. Continuous variables were analyzed using linear regression with 95% confidence intervals of their

slopes represented by dashed lines. Statistical significance was achieved if the 95% confidence intervals of the slopes of the regression lines excluded a slope of zero. No data manipulation

was performed on quantitative culture-determined viral load data points, which exceeded the upper limit of quantification. Fisher’s exact test and the Chi-squire test were used for the

contingency graphs. Statistical analyses and construction of figures were performed with GraphPad Prism Software v5.0 (La Jolla, CA). STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT This research was funded

by the National Institutes of Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD, US, grant RR16187 awarded to J.P.D. REFERENCES * El Saleeby CM, Li R, Somes GW, Dahmer MK, Quasney MW, DeVincenzo JP.

Surfactant protein A2 polymorphisms and disease severity in a respiratory syncytial virus-infected population. _J Pediatr_ 2010;156:409–14. Article CAS Google Scholar * Miyairi I,

DeVincenzo JP. Human genetic factors and respiratory syncytial virus disease severity. _Clin Microbiol Rev_ 2008;21:686–703. Article CAS Google Scholar * Thomsen SF, Stensballe LG,

Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Backer V, Bisgaard H. Increased concordance of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in identical twins. _Pediatrics_ 2008;121:493–6. Article Google Scholar *

Fraser C, Lythgoe K, Leventhal GE, et al. Virulence and pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection: an evolutionary perspective. _Science_ 2014;343:1243727. Article Google Scholar * Hakami A, Ali A,

Hakami A. Effects of hepatitis B virus mutations on its replication and liver disease severity. _Open Virol J_ 2013;7:12–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Goka EA, Vallely PJ, Mutton KJ,

Klapper PE. Mutations associated with severity of the pandemic influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. _Arch Virol_

2014;159:3167–83. Article CAS Google Scholar * Heikkinen T, Waris M, Ruuskanen O, Putto-Laurila A, Mertsola J. Incidence of acute otitis media associated with group A and B respiratory

syncytial virus infections. _Acta Paediatr_ 1995;84:419–23. Article CAS Google Scholar * Walsh EE, McConnochie KM, Long CE, Hall CB. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection is

related to virus strain. _J Infect Dis_ 1997;175:814–20. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kneyber MC, Brandenburg AH, Rothbarth PH, de Groot R, Ott A, van Steensel-Moll HA. Relationship

between clinical severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection and subtype. _Arch Dis Child_ 1996;75:137–40. Article CAS Google Scholar * McIntosh ED, De Silva LM, Oates RK. Clinical

severity of respiratory syncytial virus group A and B infection in Sydney, Australia. _Pediatr Infect Dis J_ 1993;12:815–9. Article CAS Google Scholar * Martinello RA, Chen MD, Weibel C,

Kahn JS. Correlation between respiratory syncytial virus genotype and severity of illness. _J Infect Dis_ 2002;186:839–42. Article Google Scholar * El Saleeby CM, Bush AJ, Harrison LM,

Aitken JA, Devincenzo JP. Respiratory syncytial virus load, viral dynamics, and disease severity in previously healthy naturally infected children. _J Infect Dis_ 2011;204:996–1002. Article

Google Scholar * DeVincenzo JP, El Saleeby CM, Bush AJ. Respiratory syncytial virus load predicts disease severity in previously healthy infants. _J Infect Dis_ 2005;191:1861–8. Article

Google Scholar * Devincenzo JP. Natural infection of infants with respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B: a study of frequency, disease severity, and viral load. _Pediatr Res_

2004;56:914–7. Article Google Scholar * Dick JW, Rosenthal KS. A block in glycoprotein processing correlates with small plaque morphology and virion targetting to cell-cell junctions for

an oral and an anal strain of herpes simplex virus type-1. _Arch Virol_ 1995;140:2163–81. Article CAS Google Scholar * Goel N, Mao H, Rong Q, Docherty JJ, Zimmerman D, Rosenthal KS. The

ability of an HSV strain to initiate zosteriform spread correlates with its neuroinvasive disease potential. _Arch Virol_ 2002;147:763–73. Article CAS Google Scholar * Mao H, Rosenthal

KS. Strain-dependent structural variants of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP34.5 determine viral plaque size, efficiency of glycoprotein processing, and viral release and neuroinvasive

disease potential. _J Virol_ 2003;77:3409–17. Article CAS Google Scholar * Jia Y, Moudy RM, Dupuis AP 2nd, et al. Characterization of a small plaque variant of West Nile virus isolated in

New York in 2000. _Virology_ 2007;367:339–47. Article CAS Google Scholar * Davis CT, Beasley DW, Guzman H, et al. Emergence of attenuated West Nile virus variants in Texas, 2003.

_Virology_ 2004;330:342–50. Article CAS Google Scholar * Blaney JE Jr, Johnson DH, Manipon GG, et al. Genetic basis of attenuation of dengue virus type 4 small plaque mutants with

restricted replication in suckling mice and in SCID mice transplanted with human liver cells. _Virology_ 2002;300:125–39. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rumyantsev AA, Murphy BR, Pletnev

AG. A tick-borne Langat virus mutant that is temperature sensitive and host range restricted in neuroblastoma cells and lacks neuroinvasiveness for immunodeficient mice. _J Virol_

2006;80:1427–39. Article CAS Google Scholar * Nickells M, Chambers TJ. Neuroadapted yellow fever virus 17D: determinants in the envelope protein govern neuroinvasiveness for SCID mice. _J

Virol_ 2003;77:12232–42. Article CAS Google Scholar * Vlaycheva LA, Chambers TJ. Neuroblastoma cell-adapted yellow fever 17D virus: characterization of a viral variant associated with

persistent infection and decreased virus spread. _J Virol_ 2002;76:6172–84. Article CAS Google Scholar * Vlaycheva L, Nickells M, Droll DA, Chambers TJ. Neuroblastoma cell-adapted yellow

fever virus: mutagenesis of the E protein locus involved in persistent infection and its effects on virus penetration and spread. _J Gen Virol_ 2005;86(Pt 2):413–21. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Holder BP, Simon P, Liao LE, et al. Assessing the _in vitro_ fitness of an oseltamivir-resistant seasonal A/H1N1 influenza strain using a mathematical model. _PLoS One_

2011;6:e14767. Article CAS Google Scholar * DeVincenzo JP, Wilkinson T, Vaishnaw A, et al. Viral load drives disease in humans experimentally infected with respiratory syncytial virus.

_Am J Respir Crit Care Med_ 2010;182:1305–14. Article CAS Google Scholar * Buckingham SC, Bush AJ, Devincenzo JP. Nasal quantity of respiratory syncytical virus correlates with disease

severity in hospitalized infants. _Pediatr Infect Dis J_ 2000;19:113–7. Article CAS Google Scholar * Grad YH, Newman R, Zody M, et al. Within-host whole-genome deep sequencing and

diversity analysis of human respiratory syncytial virus infection reveals dynamics of genomic diversity in the absence and presence of immune pressure. _J Virol_ 2014;88:7286–93. Article

Google Scholar * Bower JR, Mao H, Durishin C, et al. Intrastrain variants of herpes simplex virus type 1 isolated from a neonate with fatal disseminated infection differ in the ICP34.5

gene, glycoprotein processing, and neuroinvasiveness. _J Virol_ 1999;73:3843–53. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jafri HS, Wu X, Makari D, Henrickson KJ. Distribution of

respiratory syncytial virus subtypes A and B among infants presenting to the emergency department with lower respiratory tract infection or apnea. _Pediatr Infect Dis J_ 2013;32:335–40.

Article Google Scholar * Scull MA, Gillim-Ross L, Santos C, et al. Avian Influenza virus glycoproteins restrict virus replication and spread through human airway epithelium at temperatures

of the proximal airways. _PLoS Pathog_ 2009;5:e1000424. Article Google Scholar * Crowe JE Jr, Collins PL, London WT, Chanock RM, Murphy BR. A comparison in chimpanzees of the

immunogenicity and efficacy of live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) temperature-sensitive mutant vaccines and vaccinia virus recombinants that express the surface glycoproteins

of RSV. _Vaccine_ 1993;11:1395–404. Article CAS Google Scholar * Firestone CY, Whitehead SS, Collins PL, Murphy BR, Crowe JE Jr . Nucleotide sequence analysis of the respiratory syncytial

virus subgroup A cold-passaged (cp) temperature sensitive (ts) cpts-248/404 live attenuated virus vaccine candidate. _Virology_ 1996;225:419–22. Article CAS Google Scholar * Juhasz K,

Whitehead SS, Bui PT, et al. The temperature-sensitive (ts) phenotype of a cold-passaged (cp) live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate, designated cpts530, results from

a single amino acid substitution in the L protein. _J Virol_ 1997;71:5814–9. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Karron RA, Wright PF, Crowe JE Jr, et al. Evaluation of two live,

cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in chimpanzees and in human adults, infants, and children. _J Infect Dis_ 1997;176:1428–36. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Zhou B, Li Y, Speer SD, Subba A, Lin X, Wentworth DE. Engineering temperature sensitive live attenuated influenza vaccines from emerging viruses. _Vaccine_ 2012;30:3691–702.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Perkins SM, Webb DL, Torrance SA, et al. Comparison of a real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay and a culture technique for quantitative assessment of

viral load in children naturally infected with respiratory syncytial virus. _J Clin Microbiol_ 2005;43:2356–62. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors

thank April Sullivan for her technical help in the laboratory and Andrea Patters for her assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. We thank the parents and caregivers of the

participating infants and children, without whose altruism the advancement towards therapy and prevention of RSV would be impossible. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Young-In Kim and Ryan

Murphy: Y.-I.K. and R.M. shared first authorship. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Pediatrics, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee Young-In Kim, Ryan

Murphy, Sirshendu Majumdar, Lisa G. Harrison & John P. DeVincenzo * Children’s Foundation Research Institute at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee Young-In Kim, Ryan

Murphy, Sirshendu Majumdar, Lisa G. Harrison, Jody Aitken & John P. DeVincenzo * Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Biochemistry, University of Tennessee Health Science Center,

Memphis, Tennessee John P. DeVincenzo Authors * Young-In Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ryan Murphy View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sirshendu Majumdar View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lisa G. Harrison View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jody Aitken View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * John P.

DeVincenzo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to John P. DeVincenzo. POWERPOINT SLIDES POWERPOINT SLIDE

FOR FIG. 1 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 2 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 3 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 4 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 5 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 6 POWERPOINT SLIDE FOR FIG. 7 RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Kim, YI., Murphy, R., Majumdar, S. _et al._ Relating plaque morphology to respiratory syncytial virus subgroup,

viral load, and disease severity in children. _Pediatr Res_ 78, 380–388 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.122 Download citation * Received: 01 October 2014 * Accepted: 26 March 2015 *

Published: 24 June 2015 * Issue Date: October 2015 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.122 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative