Membrane potential shapes regulation of dopamine transporter trafficking at the plasma membrane

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The dopaminergic system is essential for cognitive processes, including reward, attention and motor control. In addition to DA release and availability of synaptic DA receptors,

timing and magnitude of DA neurotransmission depend on extracellular DA-level regulation by the dopamine transporter (DAT), the membrane expression and trafficking of which are highly

dynamic. Data presented here from real-time TIRF (TIRFM) and confocal microscopy coupled with surface biotinylation and electrophysiology suggest that changes in the membrane potential

alone, a universal yet dynamic cellular property, rapidly alter trafficking of DAT to and from the surface membrane. Broadly, these findings suggest that cell-surface DAT levels are

sensitive to membrane potential changes, which can rapidly drive DAT internalization from and insertion into the cell membrane, thus having an impact on the capacity for DAT to regulate

extracellular DA levels. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DYNAMIC CONTROL OF THE DOPAMINE TRANSPORTER IN NEUROTRANSMISSION AND HOMEOSTASIS Article Open access 05 March 2021

NEXT-GENERATION GRAB SENSORS FOR MONITORING DOPAMINERGIC ACTIVITY IN VIVO Article 21 October 2020 DISTINCT SUB-SECOND DOPAMINE SIGNALING IN DORSOLATERAL STRIATUM MEASURED BY A

GENETICALLY-ENCODED FLUORESCENT SENSOR Article Open access 22 September 2023 INTRODUCTION Central nervous system dopaminergic (DAergic) neurotransmission is essential in multiple

neurological functions, including cognition, extrapyramidal motor control, the reward pathway and attention1,2,3,4. In addition to the timing of vesicular release of dopamine (DA) and the

expression profiles of G-protein-coupled DA receptors5,6, one major regulator of DA signalling magnitude and timing is the DA transporter (DAT), which rapidly transports extracellular DA

into the intracellular space for vesicular re-packaging or effluxes DA through reversal of DAT-mediated transport7,8. Commonly abused psychotropic drugs, amphetamine (AMPH), methamphetamine

and cocaine achieve their effects either by inducing DA efflux through DAT and/or blocking DA uptake9,10,11. The physiological function of DAT to remove DA is coupled to the translocation of

one Cl− and two Na+ ions8,12,13, and can even function in the absence of substrate, conducting an uncoupled, cocaine-sensitive, depolarizing current under physiological conditions13,14,

which is increased in hyperpolarized states10. In addition to direct modulation of transport function, DAT density at the cell membrane, and therefore its functional capacity, is also

dynamic. Regulated trafficking mechanisms control surface-membrane DAT levels under physiological conditions15,16 and in response to DAT substrates15,16, thus having an impact on DA

homeostasis. Cell signalling molecules involved in the regulation of DAT trafficking range from protein kinase C (PKC)17,18, mitogen-activated protein kinase19 to Akt (ref. 20) among

others15,16 and determine the presence of DAT in regulated or constitutive pools segregated to specific membrane microdomains21,22,23. Many DAT substrates also influence DAT

trafficking15,24,25, including DA and AMPH, which decrease DAT surface density26,27,28, and cocaine, which increases DAT surface expression29. Interestingly, AMPH’s effects are twofold, as

it causes DAT internalization26,27,28 and a DAT-dependent membrane depolarization13,14, which suggests an influence on DAT trafficking via a voltage-dependent mechanism in addition to DAT

phosphorylation. Indeed, previous studies using striatal synaptosomes have revealed a reduction in DA uptake in depolarized (elevated KCl) conditions30,31, while _in vitro_ preparations have

suggested elevated DAT function at hyperpolarized states13. However, it is not known whether these changes in functional capacity arise from changes in ionic driving forces, essential for

DA transport, changes in DAT protein presence at the membrane or both. While changes in the cell membrane voltage state are only typically considered in terms of neurotransmitter release,

action potential generation and timing or in the activity of voltage-sensitive transmembrane proteins, it is possible that changes in membrane potential (MP) alone may rapidly and reversibly

affect DAT trafficking to and from the cell surface. Here we use confocal and total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM), biochemistry, electrophysiology and optogenetics to

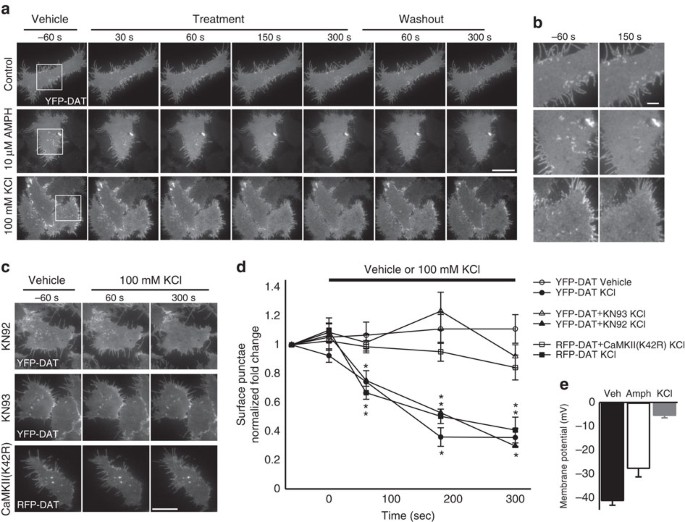

demonstrate the degree to which surface-membrane DAT levels are shaped by and sensitive to MP changes. RESULTS MP DEPOLARIZATION REDUCES MEMBRANE DAT LEVELS AMPH-mediated activation of DAT

induces a depolarizing DAT-mediated Na+ current and simultaneously causes internalization of cell-surface-membrane DAT14,28. To determine whether AMPH-induced DAT internalization was the

result of a psychostimulant-specific action or may be, in part, due to activation of voltage-sensitive mechanisms, we performed live cell TIRFM of yellow fluorescent protein-tagged DAT

(YPF-DAT) in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) cells when perfused with only extracellular solution (vehicle), 10 μM AMPH or 100 mM KCl (Fig. 1), which depolarized cells by 13.5 and 35.7 mV,

respectively (Fig. 1e). The distribution of YFP (yellow fluorescent protein)-DAT at the cell membrane (TIRFM footprint) was unchanged throughout perfusion of vehicle, whereas 10 μM AMPH

noticeably altered the YFP signal in the TIRFM footprint within the first 60 s, causing a reduction in surface-membrane high-intensity regions and puncta that did not recover in washout

(Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 1a), in line with previous reports at longer AMPH treatment durations32. Similarly, depolarizing 100-mM KCl-based external solution significantly altered

the YFP-DAT distribution in TIRFM footprint; however, the effects occurred rapidly, obvious within 30 s, and typically all YFP puncta and high-intensity regions were absent from the surface

membrane after 3 min (Fig. 1a,b,d). In contrast to AMPH, treatment with KCl resulted in the return of YFP signal profile and the reappearance of YFP puncta immediately on washout (Fig. 1a

and Supplementary Movie 1). To determine the relative specificity of this effect of depolarization for DAT, we identically depolarized HEK cells transfected with an eYFP-tagged version of an

unrelated naturally occurring membrane protein, GPR40 (ref. 33), which had a membrane distribution similar to DAT, but its trafficking appeared insensitive to depolarization (Supplementary

Fig. 1b,c). Since the depolarization induced by KCl will likely increase free [Ca2+] and trigger the activation of Ca2+-dependent signalling molecules, we chose to determine the role of

CaMKII and PKC in initiating this depolarization-induced redistribution. The depolarization-induced loss of YFP-DAT signal did not appear affected by the PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide I

(10 μM; Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the KCl depolarization-induced loss of YFP-DAT surface puncta was significantly reduced in the presence of the CaMK inhibitor KN93 (10 μM) relative

to the same treatment in the presence of the inactive homologue, KN92 (10 μM; Fig. 1c,d), which produced results similar to KCl treatment alone (Fig. 1a–d). However, because of the

KN93-induced attenuation of the depolarization-triggered Ca2+ influx (Supplementary Fig. 3), we chose to biochemically inhibit CaMKIIα specifically and assess membrane DAT using TIRFM by

co-expressing a kinase-inactive version of CaMKIIα, a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged K42R mutant and RFP (red fluorescent protein)-DAT. In response to KCl-induced depolarization,

RFP-DAT alone behaved similarly to YFP-DAT; however, when GFP-CaMKIIα(K42R) was co-expressed, KCl treatment was unable to alter the membrane distribution of RFP-DAT (Fig. 1c,d). These

changes in membrane DAT in response to depolarization (100 mM KCl application) and repolarization (washout) suggest that the MP state is capable of bidirectionally shaping the cell-surface

distribution of DAT through activation of CaMKIIα. MEMBRANE DAT REDUCTION IS CAMKIIΑ AND DYNAMIN DEPENDENT To determine the degree to which real-time changes in the YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint

were indicative of changes in DAT protein density at the cell membrane, a cell-surface biotinylation assay was used to quantify differences in membrane DAT protein levels. In YFP-DAT HEK

cells, compared with vehicle treatment (100%, _n_=17), surface DAT (Fig. 2; see Supplementary Fig. 4 for antibody validation and total protein blots) was significantly reduced following a

similar 5-min treatment as above with both 50 mM (62±6%, _n_=14) and 100 mM (70±5%, _n_=17) KCl-based external solution as well as the positive control treatments with AMPH (10 μM; 59±7%,

_n_=13) and the PKC agonist phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 2.5 μM; 53±5%, _n_=13). The CaMKIIα dependency of this effect observed in TIRFM studies was also supported by biotinylation

experiments (Fig. 2), wherein 100 mM KCl had little effect on membrane DAT protein when YFP-DAT HEK cells were transfected with the kinase-inactive, dominant-negative GFP-CaMKIIα(K42R)

(105±11%, _n_=6) or in the presence of the CaMK inhibitor KN93 (10 μM; 98±9%, _n_=9), whereas the inactive homologue KN92 did not significantly block the KCl-dependent reduction in surface

DAT (10 μM; 63±6%, _n_=12). To determine whether the reduction in membrane DAT distribution observed using TIRFM and confirmed using biotinylation was a trafficking event, we evaluated the

capacity for depolarization to induce a loss in surface DAT in the presence of Dynasore, a dynamin inhibitor34. Indeed, inhibition of dynamin by Dynasore blocked depolarization- (115±6%,

_n_=6), AMPH- (101±11%, _n_=6) and PMA-dependent (108±8%, _n_=6) internalization of DAT in HEK cells, whereas expression of CaMKIIα(K42R) only blocked depolarization- and PMA-dependent

(117±13%, _n_=6) but not AMPH-dependent (66±9%, _n_=6) internalization (Fig. 2). Importantly, treatment with 100 mM KCl did not alter surface levels of the native or overexpressed,

membrane-resident transferrin receptor in comparison with vehicle control, providing further support for the specificity of depolarization-induced downregulation of membrane DAT

(Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that CaMKIIα- and dynamin-dependent pathways are involved in depolarization-dependent DAT trafficking at the cell membrane. MP

DEPOLARIZATION INTERNALIZES JHC 1-064/DAT COMPLEXES Next, we used JHC 1-064 (ref. 35), a fluorescent cocaine analogue, to label cell membrane-resident DAT in HEK FLAG-DAT cells in

conjunction with live cell confocal microscopy to investigate whether KCl-induced membrane depolarization would drive the internalization of cell-surface JHC 1-064/DAT complexes, an approach

used previously to study DAT trafficking to defined endosome compartments _in vitro_ (Fig. 3a)36. In all cases, the presence of JHC 1-064/DAT complex puncta in the intracellular space was

limited or nonexistent at 4 °C (Fig. 3b). However, when changing bath temperature from 4 to 37 °C with either vehicle or depolarizing (iso-osmotic) 100-mM KCl-based external solution (Fig.

3b–d), the number of fluorescent punctate JHC 1-064/DAT complexes (Fig. 3c) and average intracellular fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3d) were significantly greater in depolarizing KCl-based

external solution (3.2±0.3 puncta per cell; normalized fold change in intracellular JHC 1-064 intensity: 0.26±0.05) compared with vehicle (1.7±0.2 puncta per cell; normalized fold change in

intracellular JHC 1-064 intensity: −0.10±0.05). MP DEPOLARIZATION REDISTRIBUTES DAT INTO EARLY ENDOSOMES To determine the identity of the intracellular destination of

depolarization-dependent internalized DAT, fluorescent versions of the endosome markers (which were not apparent at the cell membrane in TIRFM; see Supplementary Fig. 6), EEA1

(TagRFP-T-EEA1) that marks early endosomes or the recycling endosome marker Rab11 (DsRed-Rab11), were expressed in HEK YFP-DAT cells and then treated with standard external solution

(vehicle), iso-osmotic 100-mM KCl-based external solution for 5 min or 10 μM AMPH for 5 min as a temporal comparison. Another time point of 60 min AMPH (10μM) treatment was used as a

positive control as it has been shown previously to cause DAT internalization to specific endosomes18,37,38,39, and would thus allow for comparability to previous work. Average Pearson

correlation coefficients per cell for intracellular YFP-DAT and TagRFP-T-EEA1 or DsRed-Rab11 in vehicle (EEA1: 0.17±0.01; Rab11: 0.19±0.01) were significantly less than in cells treated with

AMPH at 5 min for EEA1 (0.32±0.03; Fig. 4a,b) and Rab11 (0.47±0.06; Fig. 4c,d), while 60-min AMPH treatment increased YFP-DAT association with EEA1 (0.24±0.01; Fig. 4a,b), but not Rab11

(0.22±0.15; Fig. 4c,d). Similarly, depolarizing conditions significantly enhanced the co-localization of intracellular YFP-DAT with EEA1 (0.30±0.02; Fig. 4a,b) over vehicle and 60-min AMPH

treatments, although comparable to the 5-min AMPH treatment. The treatment had no effect on the degree of association of intracellular YFP-DAT with Rab11 (0.16±0.07; Fig. 4c,d) compared with

vehicle. While biotinylation and confocal imaging inherently lack the temporal resolution of TIRFM, the collective results indicate that MP depolarization rapidly reduces

cell-surface-membrane DAT and internalizes the transporter to intracellular early endosome compartments, suggesting that membrane DAT levels and DAT trafficking may be partially dependent on

the MP state and therefore could change rapidly with MP fluctuation on local changes in the activity of receptors, ion transporters and channels. CHANGE IN MP STATE ALTERS CELL SURFACE

MEMBRANE DAT LEVELS To further examine whether the membrane distribution of DAT is altered in response to MP changes (depolarization and hyperpolarization), we employed simultaneous

single-cell TIRFM and whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology (Fig. 5a). This technique allowed for time-resolved, bidirectional and precise control of the MP and provided internal controls

in adjacent non-clamped cells. Acquisition of TIRFM image sequences (5-s intervals) throughout the course of 5-min duration voltage steps indicated that the surface YFP-DAT signal is stable

during whole-cell voltage clamp at −40 mV (typical MP for YFP-DAT HEK cells; Fig. 5b–e), but MP changes from baseline to hyperpolarized (−60 mV; Fig. 5b,f–h) or depolarized (+20 mV; Fig.

5b,i–k) potentials could rapidly (between frames, 5 s duration) increase or reduce, respectively, YFP-DAT puncta in the TIRFM footprint (Fig. 5b). In some cases, the 5-s interframe interval

during depolarization was sufficient to eliminate all DAT puncta from the cell surface, and hyperpolarization to −60 mV caused complete recovery of the fluorescent signal profile within 5–10

s (Fig. 5b). The effect of the hyperpolarizing voltage step on the TIRFM footprint intensity of patch-clamped cells rapidly increased, typically plateauing within 5 min, and began to

reverse (decrease in intensity) following return of the membrane voltage to −40 mV (Fig. 5f). Continuous clamping of the MP at −40 mV did not significantly alter the YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint

intensity at 3 min relative to adjacent cells (_n_=4 clamped, four adjacent cells; _P_>0.05; Fig. 5c–e). However, when comparing intensity changes between clamped and adjacent cells 3 min

into the voltage step, stepping the MP to −60 mV significantly increased the YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint intensity (_n_=5 clamped, five adjacent cells; _P_<0.01; Fig. 5f–h), while stepping

to +20 mV produced the opposite effect (_n_=5 clamped, five adjacent cells; _P_<0.01; Fig. 5i–k). Further comparison of voltage effects between only cells clamped at −40, −60 or +20 mV

also indicates a significant difference in normalized YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint intensity for the −60 mV (_n_=5 cells; _P_<0.05) and +20 mV (_n_=5 cells; _P_<0.001) condition when

compared with the −40 mV (_n_=4 cells) condition 5 min following the voltage change (Fig. 5l). CHANGE IN MP STATE ALTERS DAT-MEDIATED CURRENT Since the mere presence of DAT at the cell

surface (YFP fluorescence signal) is not necessarily indicative of relative DAT function, we sought to determine whether MP change-induced variations in the surface DAT density (Fig. 5)

correlated with the uncoupled DAT-mediated current. To investigate this, as in previous TIRFM experiments, the MP was clamped for 5 min at +20, −40 or −60 mV but was followed by acquisition

of a baseline IV curve (Fig. 6a). The subsequent GBR12935-sensitive current was then taken as the DAT-mediated current for each cell for a given condition. Cells clamped at −40 mV (near

their endogenous resting MP) had a DAT-mediated current amplitude of −15.3±2.16 pA (_n_=8; Fig. 6c–f, black). However, when cells were depolarized to +20 mV for 5 min (Fig. 6c–f, red), the

DAT-mediated current (−8.8±1.6 pA, _n_=7) was significantly reduced by 42.3% (_P_<0.05), and cells hyperpolarized to −60 mV for 5 min (Fig. 6c–f, blue) displayed a 47.7% larger

(_P_<0.05) DAT-mediated current (−22.6±2.0 pA, _n_=5) compared with cells held at −40 mV. For comparison of MP state-dependent changes in YFP-DAT membrane density (Fig. 5) and DAT

functional capacity, the average fold change in YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint intensity and DAT-mediated current amplitude for each MP-holding potential state are plotted against each other (Fig.

6f), indicating a positive correlation between the two measures. While the cell-surface-membrane DAT levels (TIRFM) are influenced by the MP state, these data imply that functional DAT may

be particularly influenced by MP state changes as they are more profoundly affected. NEURONAL MP CHANGES ALTER SURFACE-MEMBRANE DAT LEVELS To determine whether MP influences surface-membrane

DAT density in functional neurons, real-time imaging of membrane DAT (TIRFM fluorescence footprint) was coupled with two characterized non-invasive methods (Supplementary Fig. 7) of

transient reliable membrane depolarization and hyperpolarization: 100-mM KCl focal application (Fig. 7a) and archaerhodopsin (Arch) activation (Fig. 7b), respectively. Cultured primary

neurons were transfected with TagRFP-T-DAT (RFP-DAT) or CFP-DAT with or without co-transfection with Arch-YFP (Arch-YFP; Supplementary Fig. 7) and were subjected to whole-cell recordings

(K-gluconate-based internal solution) or imaging in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX) and receptor blocker cocktail (see Methods), unless otherwise indicated. Pressure application of

KCl-based external solution induced a reversible 36.9±8.3-mV membrane depolarization in RFP-DAT-expressing neurons (Fig. 7a,c–e), and photo-activation (590 nm) of Arch caused a reversible

−23.3±3.2-mV membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 7a,c–e). In the absence of TTX, Arch activation suppressed action potential firing and induced a rebound burst when the light was turned off

(Fig. 7b) and was relatively stable over long pulse durations (Supplementary Fig. 7) used for subsequent imaging experiments40. The MP of neurons lacking Arch-YFP expression was unaffected

by 590-nm light stimulation. On characterizing the reliability of these tools, we performed simultaneous TIRFM of primary culture neurons (Fig. 7f) during each manipulation (Supplementary

Fig. 7b and Fig. 7g,h). TIRFM of neurons expressing RFP-DAT while focally applying 100-mM KCl-based external solution (Supplementary Fig. 7b) for a short duration (45 s) caused a rapid and

dramatic reduction (−21.1±8.5%) in the RFP-DAT TIRFM footprint intensity (Supplementary Movie 2), while vehicle application had no effect (Fig. 7g). Similarly, bath application of 100-mM

KCl-based external solution also enhanced the internalization of endogenous DAT in primary neurons labelled with JHC 1-064, causing a dramatic increase in JHC 1-064 complexes in the

intracellular space (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, simultaneous MP hyperpolarization via activation of Arch by 590-nm light staggered with TIRFM imaging of CFP-DAT (Fig. 7h) indicated

that hyperpolarization caused a reversible increase (+9.0±3.5%) in CFP-DAT intensity in the TIRFM footprint overtime, which stabilized after 120 s (Fig. 7h and Supplementary Movie 3). No

significant change (−3.8±3.3%) in CFP-DAT TIRFM footprint intensity was observed in neurons lacking Arch-YFP expression (Fig. 7h). These KCl-induced decreases and Arch activation-induced

increases in neuronal cell-surface DAT TIRFM signal, which parallel MP state-dependent changes in the surface density of DAT protein (Figs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and DAT function (Fig. 6) in YFP-DAT

HEK cells, were significantly different from their respective controls (depolarization: _P_<0.05, hyperpolarization: _P_<0.05; Fig. 7i). DISCUSSION The presence of DAT at the cell

membrane is crucial in the regulation of DAergic signalling, timing and magnitude throughout the brain, and thus any alteration in the functional capacity of the transporter may

significantly have an impact on neurological functions in which DA is involved. Previous studies have demonstrated that KCl-induced depolarization reduces DA uptake30,31, and that membrane

hyperpolarization increases DAT-mediated inward current and DA uptake13, albeit with an unknown mechanism. Here we asked whether changes in MP alone may rapidly and reversibly regulate DAT

trafficking. One aspect regulating transporter function is that the trafficking of mature DAT to and from the cell membrane is a highly regulated process, which is affected in various

disease states and by the activity of DAT-targeting psychostimulants. Using live cell TIRFM and biotinylation on identically treated HEK cells expressing YFP-DAT, we determined that membrane

depolarization alone could induce a CaMKIIα- and dynamin-dependent (Figs 1 and 2) rapid reversible (increase in hyperpolarization recovery) reduction in membrane DAT (Fig. 1 and

Supplementary Movie 1). This depolarization-induced effect on DAT distribution in the TIRFM footprint was distinctly different when compared with the effects of AMPH, which did not recover

as quickly. Another difference between AMPH- and depolarization-induced DAT internalization is the insensitivity of AMPH-induced internalization to the loss of CaMKIIα activity through the

coexpression of a dominant-negative, kinase-inactive CaMKIIα (Fig. 2), which, along with the sensitivity of both versions to KN93, may suggest that different isoforms of the kinase may have

distinctly different roles in regard to regulating DAT function. Notably, similar fast changes in membrane DAT levels have been reported using this approach with acute AMPH exposure41.

However, the direction of the AMPH effect on human DAT using the multifaceted approach reported here contrasts with this previous finding and could be due to intrinsic differences between

rat and human DAT, AMPH concentrations and/or cell types. To determine the degree of DAT internalization, with the DAT-specific fluorescent cocaine analogue, JHC 1-064 (ref. 36), we followed

the distribution of JHC 1-064 fluorescence (JHC 1-064/DAT complexes; Fig. 3) when cells were left at rest or depolarized. These data suggested that indeed membrane-resident DAT was being

more rapidly brought into the intracellular space when depolarized as compared with constitutive internalization (Fig. 3c,d). While biotinylation and confocal imaging inherently lack the

temporal resolution of TIRFM, together, results indicate that in contrast to the effects of AMPH on DAT, depolarization resulted in DAT being segregated specifically into early endosome

compartments (EEA1), but not recycling endosomes (Rab11; Fig. 4). This divergence in the destination of internalized DAT in cells treated with AMPH versus those simply depolarized again

suggests the involvement of differing mechanisms, which may leave initially internalized DAT residing in early endosomes free to transition into rapid recycling endosomes, distinct from

recycling endosomes42, putatively underlying the faster recovery to the membrane surface during hyperpolarization. Although few studies have examined DAT activity immediately after

depolarization or following the return to the resting hyperpolarized state, our data provide a potential mechanism for the decreased DA uptake in striatal synaptosomes during the fast phase

of depolarization-induced DA release31. Therefore, to determine any bidirectionality of the KCl effect on DAT trafficking, we used whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques to clamp the MP of

YFP-DAT HEK cells while performing TIRFM simultaneously (Fig. 5). Once cells were clamped near their endogenous resting potential (−40 mV), the YFP-DAT TIRFM footprint was relatively similar

over time (Fig. 5c–e). However, when stepping the membrane-holding potential from −40 mV to a hyperpolarized potential, an increase in YFP-DAT intensity and puncta number in the TIRFM

footprint began immediately (Fig. 5b) and plateaued after 3 min (Fig. 5f–h). In contrast, when cells were depolarized the opposite effect occurred with a loss of YFP-DAT signal, which

paralleled the effects seen in the presence of depolarizing KCl (Fig. 5i–k). In fact, the ∼10% change in YFP-DAT intensity directly corresponded to reductions in DAT-mediated

(GBR12935-sensitive) current when cells were clamped at depolarized or hyperpolarized potentials (Fig. 6). On the basis of these data and the known electrogenic nature of DAT-mediated DA

uptake and efflux, we hypothesize that at depolarized conditions, where efflux is more likely to occur10, the cell may actively attenuate this efflux by downregulating DAT at the membrane.

In contrast, membrane hyperpolarization, known to facilitate DA uptake13, may be doing so through interactions with ionic driving forces and increases in membrane DAT. With two tools that

induced reversible and reliable depolarization (focal KCl application) or hyperpolarization (Arch activation) of magnitudes, similar to those used in previous experiments (Fig. 7a–e), we

used TIRFM to monitor fluorescent-tagged DAT expressed in midbrain primary cultures during MP manipulation. The effect of these manipulations on membrane DAT levels were larger than in HEK

cells using methods that induced similar voltage differences, implying that these effects are indeed applicable to neuronal populations and results obtained using HEK cells are relevant to

shaping conclusions about MP-dependent trafficking of DAT in the nervous system. Together, these data indicate that, while the magnitude of change in membrane DAT levels due to MP changes

varies depending on the assay, all changes observed are in a physiologically relevant range and the direction of the effect (increase or decrease) is in agreement across all examinations.

This effect of the MP on DAT trafficking sheds light on an additional mechanism by which the activation of hyperpolarizing D2Rs may be altering DA transport. The activation of D2Rs has long

been understood to enhance DAT function43, and previous studies have suggested that a D2R activation initiates a signalling cascade to upregulate cell-surface DAT19. Although others have

examined how changes in the neuronal MP similarly to those initiated by D2R activation may alter DAT function and found no impact on [3H]-DA uptake44, those experiments were performed at

room temperature, which likely attenuates trafficking rates as opposed to the studies here conducted at near-physiological temperatures (37 °C). Thus, this methodological difference may

explain the discrepancies between that [3H]-DA uptake study44 relative to the data presented here. Nevertheless, collectively this study and previous studies support the involvement of

multifaceted regulatory mechanisms for DAT trafficking that are substrate-, kinase- and activity-dependent. The existence of multiple regulatory mechanisms supports the notion that the DAT

proteins at the membrane are responsive to diverse regulatory mechanisms. The overriding mechanism for activation of a given trafficking pathway will be determined by the nature of the

stimulation and the availability of specific regulatory constituents. DA signalling is crucial in many neurological functions, as aberrations in DA neurotransmission contribute to multiple

neuropsychiatric disorders, including addiction3,45, Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders46,47,48, schizophrenia49,50 and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)2, all of which

have been linked to how extracellular DA may be mishandled by altered DAT expression and function23,50,51. As a result, disease-related deviations from physiological states and variations

in neuronal MPs may be altering the functional capacity of DAT by affecting its trafficking to and from the membrane. This dynamic balance of electrophysiological and biochemical processes

to regulate subtle but essential aspects of neurotransmission opens a range of possibilities for exploring related aberrations in disease states and in pharmacotherapy targeting this

interaction. Broadly, the regulation of protein (DAT) trafficking by the MP may provide additional means by which plasticity (for example, activity-dependent changes) in DAergic and possibly

non-DAergic systems is maintained and controlled. METHODS CELL CULTURE _Cell lines_. HEK cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged or YFP-tagged human DAT (hDAT), HEK FLAG-DAT (refs 52, 53) or

YFP-DAT HEK (ref. 54), respectively, were a generous gift from Dr Jonathan Javitch (Colombia University) prepared from HEK293 EM4 as previously described55,56. The addition of the YFP tag

and FLAG epitope to hDAT is a widely used construct and has not been shown to alter basic functional properties of the transporter or other transporter-mediated activity24,52,53,55,57. HEK

cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% L-glutamine, penicillin (50 μl ml−1) and streptomycin (50 μl ml−1) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were typically

passaged and/or used for electrophysiology or imaging experiments after reaching 60–80% of full confluency (every 2–3 days). To induce expression of constructs not stably expressed in HEK

cell lines, HEK293 EM4 cells were transfected using a standard calcium phosphate protocol. Transfected cells were used in experiments 12–36 h after transfection. _Midbrain primary neuron

culture_. All animals used were housed in the University of Florida’s McKnight Brain Institute animal care facility, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care

International-accredited facility. The University of Florida’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved of all procedures undertaken. Primary cultures of the ventral midbrain

containing DAergic neurons were prepared as previously described9,57,58 and are described here in brief. The ventral midbrain, including DA neuron-rich regions, was acutely dissociated and

isolated under sterile conditions from 0- to 2-day-old C57Bl/6J mice of both sexes and incubated at 34–36 °C under continuous oxygenation for 30 min in a dissociation medium, containing (in

mM): 116 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 2 NaH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 1.3 cysteine, 0.5 EDTA, 0.5 kynurenic acid and containing 20 units ml−1 papain. Subsequently, tissue was triturated with

fire-polished Pasteur pipettes in glial medium, containing (in %): 50 MEM, 38.5 FBS, 7.7 penicillin/streptomycin, 2.9 D-glucose (45%) and 0.9 glutamine (200 mM). Dissociated cells were

pelleted at 450_g_ for 10 min and were re-suspended in glial medium. Cells were plated on 12-mm round coverslips placed in 35 × 10 mm style tissue culture Petri dishes or glass-bottom 35 ×

10 mm (MatTek, Ashland, MA) coated with 100 μg ml−1 poly-D-lysine and 5 μg ml−1 laminin. One hour after plating, the medium was changed to neuronal medium, containing (in %): 2 MEM, 75

Ham’s-F12 medium, 19 heat-inactivated horse serum, 2 FBS, 1.56 D-glucose (45%), 0.04 insulin (0.025 g ml−1) and 0.4 apotransferrin (50 mg ml−1). Neuronal cultures were transfected with

TAGRFP-T-DAT, CFP-DAT and/or Arch-YFP constructs via nucleofection (Mouse Nucleofector Kit, programme O-005, Lonza Group Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) immediately before plating or via calcium

phosphate 3–5 days after plating using standard protocols. All cultures were used at 7–9 days _in vitro_ (DIV) and 4–9 days post transfection. No difference between transfection

methodologies was observed regarding protein expression level and/or function. PLASMID CONSTRUCTS The plasmid coding for the cyan fluorescent protein-tagged DAT was described previously59,60

and was provided as a generous gift from Dr Alexander Sorkin (University of Pittsburgh). The RFP-tagged hDAT (TagRFP-T-DAT)34, generated as previously described, was a gift from Dr Haley

Melikian (University of Massachusetts), and the construct for fatty-acid receptor GPR40-eYFP driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter was a gift from Dr Sergei Zolotukhin and Seth Currlin

(University of Florida). DsRed-Rab11 WT61, a recycling endosome marker, was a gift from Richard Pagano (Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Addgene plasmid #12679). TagRFP-T-EEA1 (ref. 62), an early

endosome marker, was provided by Silvia Corvera (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Addgene plasmid #42635). The GFP-C1-CAMKIIα-K42R (ref. 63) was a gift from Tobias Meyer

(Stanford University, Addgene plasmid #21221), and the pTfR-PAmCherry1 (ref. 64) plasmid was a gift from Vladislav Verkhusha (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Addgene plasmid #31948). To

confer optical control of MP hyperpolarization, neuronal cultures were transfected with AAV-CaMKα-eArch 3.0-EYFP plasmid, a generous gift from Dr Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University). Arch

was chosen for its ability to induce large magnitude H+-current-hyperpolarizing shifts (10–50 mV) in the neuronal MP, which were relatively stable over seconds to minutes with minimal decay

when continuously activated40,65. ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY HEK cells and cultured neurons were visualized with a × 60 objective on an inverted Nikon Ti Eclipse microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY).

All currents and MPs were recorded via an Axoclamp 200A amplifier using the whole-cell configuration after forming a high-resistance seal in the cell-attached configuration (>1 MΩ). All

signals were digitized with a Digidata 1440A at 10 kHz, and a 5-kHz low-pass Bessel filter was applied during acquisition. An additional 2-kHz Gaussian filter was applied to all traces for

presentation only. The standard external solution for electrophysiology experiments using HEK cells was the same used in all microscopy and biochemistry experiments and contained (in mM) the

following: 130 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 34 Dextrose, 1.5 CaCl2, 0.5 MgSO4 and 1.3 KH2PO4, with a pH of 7.35 and osmolarity of 275–290 mOsm. Pipettes for whole-cell recordings were pulled from

borosilicate glass on a P-2000 laser-based puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Pipettes used for recording the MP (3–6 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM) the

following: 130 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2 adjusted to pH 7.35 and osmolarity of 262 mOsm. For recording of DAT-mediated whole-cell currents, pipettes were filled with (in

mM) the following: 120 CsCl, 30 dextrose, 10 HEPES, 1.1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2 and 0.1 CaCl2 adjusted to pH 7.35 and osmolarity of 264 mOsm. Recordings were performed at 37 °C. For determining

DAT-mediated current and IV changes at different holding potentials, a stable IV (−100 to +40 in 20 mV steps) was generated after 5 min of continuously holding the cell at the given

potential (−60, −40 or +20 mV), and then the DAT blocker GBR12935 (20 μM) was added to the bath and subsequent IVs were measured every 30–60 s. To determine the DAT-mediated current

amplitude, the IV in the presence of GBR12935 (Fig. 6c; protocol #2; grey traces) was subtracted from the preGBR12935 IV following the prolonged clamp of the MP (Fig. 6c; protocol #1;

red=+20 mV, black=−40 mV, blue=−60 mV) to yield the DAT-mediated (GBR12935-sensitive) current at each voltage step of the IV (the curve displayed in Fig. 6d) corresponding with manipulation

of the MP state in previous TIRFM experiments (Fig. 5). For statistical comparisons between groups (Fig. 6e,f), the DAT-mediated current (pre-GBR12935–post-GBR12935 amplitude) at the −100 mV

step, where DAT-mediated current is largest, was used. For recording and imaging of DAergic neurons in primary culture, the external solution contained (in mM) the following: 146 NaCl, 5

HEPES, 5 KCl, 30 Dextrose, 2.5 CaCl2 and 1.2 MgCl2, with pH 7.35 and had an osmolarity of 290–300 mOsm. Patch pipettes (4–6 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution containing the following

(in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP and 0.2 Na-GTP, pH adjusted to 7.35 and osmolarity of 270 mOsm. Recordings of the neuronal MP were corrected offline

for a calculated liquid junction potential of 16.1 mV. All recordings occured at 37 °C. MICROSCOPY All microscopy analyses were performed at 37 °C, and cells were washed twice with external

solution as described above before all experiments. For all imaging experiments, cells/neurons were set on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) with glass thickness of 0.13–0.16

mm (TIRFM) or 0.085–0.13 mm (confocal). Wide-field fluorescence images were acquired identically to TIRFM images; however, a Lambda LS Xenon Arc Lamp provided the light source that bypassed

the additional TIRFM mirror set and was passed through appropriate excitation (Ex)/emission (Em) filters and dichroic mirror. Microscopy data were analysed in the Nikon’s NIS Elements

software. _TIRFM_. TIRFM imaging of HEK cells and neurons plated on poly-d-lysine-coated dishes was performed at 37 °C using Nikon Eclipse TE-2000-U inverted microscope, with a × 60 1.49

numerical aperture (NA) objective and equipped with a multiline solid-state laser system (470, 514 and 561 nm) and appropriate filter combination for YFP (Ex: 514 nm/Em: 535 nm), TagRFP (Ex:

561 nm/Em: 584 nm) and CFP (Ex: 445 nm/Em: 475 nm), similar to as previously described57. TIRFM was achieved via the ‘through-the-objective’ laser guidance method with the laser incident

angle set to 76°, which is greater than the critical angle of 62° and generated an evanescent field depth between 66 and 72 nm depending on the wavelength of light used. Temperature control

was maintained with a stage and an objective heater (20/20 Technology Inc.). Image exposure time was coupled with laser excitation duration at 200–300 ms, and laser intensity was maintained

at 40–60% of maximum intensity, but neither changed throughout the course of a given experiment. Images were detected digitally using an attached CoolSNAP HQ2 CCD camera and stored on a

computer hard drive at 5–10-s intervals. For imaging of HEK cells, baseline images were acquired during perfusion of standard external solution before changing the solution to 100-mM

KCl-based external solution (osmotically balanced) or 10 μM AMPH, prepared as described above, or throughout the entirety of being held in the whole-cell configuration. For simultaneous

patch-clamp and TIRFM, membrane-holding potentials of +20, −40 and −60 mV were determined in preliminary experiments to approximate endogenous resting potential of these cells (−40 mV), to

mimic the effects of 100-m KCl depolarization (+20 mV) and to oppose depolarizing effects of +20 mV with a similar magnitude of change (−60 mV). For quantification of cell-surface

fluorescence intensity of isolated HEK cells and primary culture neurons, regions of interest were created, including the TIRFM footprint of each HEK cell in its entirety or the neuron’s

soma. For all image sequences, a background ROI similar to the size of a cell was placed in a region devoid of cells/fluorescence and was subtracted from the entire image and recalculated

for each frame. The mean intensity (in arbitrary fluorescent units) over time was monitored and plotted/analysed as a fraction of the baseline intensity (the mean raw intensity of all frames

within 30–60s before initiation of indicated manipulation) and used for analysis. Bleaching was controlled for in two ways. The first was the inclusion of a vehicle group and/or non-patched

adjacent cells for each assay appropriately. However, because of relatively large observed cell-to-cell variability in the change in baseline fluorescence over time ranging from −3.0 to

+2.1% per min (average 0.4±0.3% per min), a correction factor or rate was determined for each cell and was used to account for this change in each cell. Since the bleaching rate with the

current TIRFM imaging parameters was linear, a linear fit was generated for 120 s before a solution change and was used to determine that the rate of bleaching was extrapolated over the

entire 12–15-min experiment. This projected rate of change in fluorescence intensity due to bleaching was then accounted for during each experiment. _Confocal microscopy and JHC 1-064

labelling of DAT_. Imaging of YFP-DAT (ex: 514 nm, em: 540/30 nm), mCherry, dsRed and JHC 1-064 (all ex: 561 nm, em: 585/65 nm) was performed using the Nikon A1R confocal system mounted on a

Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope (Nikon) using a × 60 1.49 NA Plan-Apo objective (Nikon). For YFP-DAT and endosome co-localization experiments, YFP-DAT HEK cells grown on glass-bottom

dishes and transfected with TagRFP-T-EEA1 or DsRed-Rab11 were treated with either 100 mM KCl for 5 min, 10 μM AMPH for 1 h or with standard external solution vehicle throughout all the

experiments at 37 ° C. After the treatment, the dishes were placed on ice and washed with the ice-cold standard external solution, then washed two more times with ice-cold PBS solution and

then fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then washed and imaged using identical imaging parameters (for example, laser power, gain, and so on) immediately in PBS. For co-localization

analysis, a region of interest (ROI) was drawn over the intracellular space of each cell in the raw image and the Pearson correlation coefficient for the two channels was calculated on a

cell-by-cell basis in NIS Elements (Nikon). For clarity and image display only, a single-count 3 × 3 pixel matrix smooth was applied, and intensity of all pixels was enhanced by 40%. The

fluorescent cocaine analogue, JHC 1-064, which has a high affinity for DAT, was used as previously described to selectively label membrane-resident DAT35,36,38,66. When YFP-DAT HEK cells had

reached 60–80% confluency after 2–3 days or midbrain primary culture neurons had reached DIV 5, they were washed twice with the appropriate standard external solution and incubated with

10–20 nM JHC 1-064 for a minimum of 30 min at 4 °C. After at least 30 min, the JHC 1-064-containing solution was removed and replaced with fresh 4 °C external solution. Immediately, the dish

was placed on the stage, and cells were selected and a baseline image was acquired. Following acquisition, the cold solution was removed and replaced with either vehicle or KCl-based

external solution at 37 °C, and images were acquired every 5 min. Imaging parameters (for example, laser power, gain, pinhole, and so on) were identical for images of HEK cells and were

within the imaging series of each neuron. For analysis of JHC 1-064/DAT complexes in HEK cells, an area devoid of cells was selected and used as a background ROI, and the mean pixel

intensity of this region was subtracted from intensity of all pixels. For determination of the mean intracellular intensity, an ROI was drawn within the boundaries of each cell and the mean

intensity (normalizing for changes in cell size) was again normalized to the intensity of the entire image to account for bleaching and was plotted as a fraction of the initial internal

fluorescence in the original control 4 °C image67. For manual counts of intracellular JHC 1-064 puncta and clarity for display (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8), all images were processed

identically. BIOTINYLATION ASSAY For biotinylation assays, YFP-DAT HEK cells or parental HEK293 cells were plated on 24-well poly-D-lysine-coated plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per

well and transfected with either GFP-C1-CaMKIIα-K42R or pTfR-PAmCherry1, as previously described68. Forty-eight to ninety-six hours after plating, cells were pre-treated (30 min) with

external solution (vehicle) or 80 μM Dynasore, followed by 30-min treatment with vehicle, vehicle+10 μM KN92 or vehicle+10 μMKN93. Cells were then washed and treated for 5 min with either

vehicle, 10 μM AMPH, 2.5 μM PMA, iso-osmotic 50 mM KCl, iso-osmotic 100 mM KCl, 100 mM KCl+KN92 or 100 mM KCl+KN93. Cell-surface proteins were then biotinylated and analysed via western blot

analysis as described previously69. Total protein concentrations for each sample were determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific), and the resulting values were

used to load equal amounts of protein for each sample when conducting SDS–PAGE. Blots of total and surface protein (Supplementary Figs 4c,d and 5c for original blots) were probed with an

N-terminal-targeted anti-DAT monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; mAb16 (ref. 70); a gift from Dr Roxanne Vaughan of the University of North Dakota) or an anti-transferrin receptor antibody

(1:1,000; C2F2, BD Biosciences), and the density of the immunoblot bands was quantitated using ImageJ (NIH) or Image Studio (LI-COR). Prism5 (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis

following normalization of surface values to vehicle and determination of the vehicle variance by normalizing to AMPH. DRUG/SOLUTION APPLICATION AND OPTICAL STIMULATION In electrophysiology,

microscopy and biochemistry experiments, increased KCl concentrations (100 mM) were achieved by replacing NaCl in the standard external solution or ACSF with KCl in an equa-molar manner,

conserving osmolarity. For TIRFM imaging of HEK cells, vehicle (standard external solution), the KCl-based external solution or 10 μM AMPH was applied via bath perfusion using a laminar flow

insert for 35-mm Petri dishes at a rate of 2 ml min−1. For neuronal recordings and TIRF microscopy, vehicle or KCl-based external solution was applied via pressure (2 psi) injection from a

pipette identical to recording pipettes positioned 20 μm from the cell body. HEK293 or YFP-DAT HEK cells were exposed to either 80 μM dynasore34 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 μM KN92, 10 μM

KN93 or 10 μM BIM (all from EMD Millipore) for 25–30 min before and throughout treatment with vehicle or 100 mM KCl to maintain the respective inhibition of dynamin, CaMK and PKC throughout

each imaging or biotinylation experiment as indicated. For steady-state photo-activation of eArch3.0 in cultured neurons, 590-nm light was generated from a light-emitting diode (LED) source

(Thorlabs) and coupled to an optical fibre and placed at a 45 degree angle, with the tip 150–200 μm from the cell body. The output at the fibre tip (200 μm diameter) was regulated via a

potentiometer on the externally-triggered LED driver and was calibrated so that the light power density at the tip was 15 mW mm−2. Changes in MP in response to eArch 3.0 activation were

determined by taking the average MP over 50 ms before light onset and the last 50 ms of a 1-s light pulse. DATA ANALYSIS All data were analysed with Microsoft Excel, IBM SPSS, Prism5 or Igor

Pro. Statistical analyses used for comparison are identified in the legend, and all values are the mean±s.e.m., unless otherwise stated. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Richardson, B. D. _et al_. Membrane potential shapes regulation of dopamine transporter trafficking at the plasma membrane. _Nat. Commun._ 7:10423 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10423 (2016). REFERENCES

* Schultz, W. Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. _Annu. Rev. Neurosci._ 30, 259–288 (2007) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Nieoullon, A. Dopamine and the regulation of

cognition and attention. _Prog. Neurobiol._ 67, 53–83 (2002) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Koob, G. F. & Volkow, N. D. Neurocircuitry of addiction. _Neuropsychopharmacology_ 35,

217–238 (2010) . Article Google Scholar * Jaber, M., Robinson, S. W., Missale, C. & Caron, M. G. Dopamine receptors and brain function. _Neuropharmacology_ 35, 1503–1519 (1996) .

Article CAS Google Scholar * Mundorf, M. L., Troyer, K. P., Hochstetler, S. E., Near, J. A. & Wightman, R. M. Vesicular Ca(2+) participates in the catalysis of exocytosis. _J. Biol.

Chem._ 275, 9136–9142 (2000) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Beaulieu, J.-M. & Gainetdinov, R. R. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. _Pharmacol. Rev._

63, 182–217 (2011) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Jaber, M., Jones, S., Giros, B. & Caron, M. G. The dopamine transporter: a crucial component regulating dopamine transmission. _Mov.

Disord._ 12, 629–633 (1997) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Sitte, H. H. et al. Carrier-mediated release, transport rates, and charge transfer induced by amphetamine, tyramine, and

dopamine in mammalian cells transfected with the human dopamine transporter. _J. Neurochem._ 71, 1289–1297 (1998) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Kahlig, K. M. et al. Amphetamine induces

dopamine efflux through a dopamine transporter channel. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 102, 3495–3500 (2005) . Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Khoshbouei, H., Wang, H., Lechleiter, J. D.,

Javitch, J. A. & Galli, A. Amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. A voltage-sensitive and intracellular Na+-dependent mechanism. _J. Biol. Chem._ 278, 12070–12077 (2003) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Amara, S. G. & Sonders, M. S. Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. _Drug Alcohol Depend._ 51, 87–96 (1998) . Article CAS Google

Scholar * DeFelice, L. J. & Galli, A. Electrophysiological analysis of transporter function. _Adv Pharmacol_ 42, 186–190 (1998) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Sonders, M. S., Zhu, S.

J., Zahniser, N. R., Kavanaugh, M. P. & Amara, S. G. Multiple ionic conductances of the human dopamine transporter: the actions of dopamine and psychostimulants. _J. Neurosci._ 17,

960–974 (1997) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Ingram, S. L., Prasad, B. M. & Amara, S. G. Dopamine transporter-mediated conductances increase excitability of midbrain dopamine

neurons. _Nat. Neurosci._ 5, 971–978 (2002) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Schmitt, K. C. & Reith, M. E. a. Regulation of the dopamine transporter: aspects relevant to psychostimulant

drugs of abuse. _Ann. N Y Acad. Sci._ 1187, 316–340 (2010) . Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Mortensen, O. V. & Amara, S. G. Dynamic regulation of the dopamine transporter. _Eur.

J. Pharmacol._ 479, 159–170 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Pristupa, Z. B. et al. Protein kinase-mediated bidirectional trafficking and functional regulation of the human dopamine

transporter. _Synapse_ 30, 79–87 (1998) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Sorkina, T., Hoover, B. R., Zahniser, N. R. & Sorkin, A. Constitutive and protein kinase C-induced

internalization of the dopamine transporter is mediated by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. _Traffic_ 6, 157–170 (2005) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Moron, J. A. et al. Mitogen-activated

protein kinase regulates dopamine transporter surface expression and dopamine transport capacity. _J. Neurosci._ 23, 8480–8488 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Wei, Y. et al.

Dopamine transporter activity mediates amphetamine-induced inhibition of Akt through a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II-dependent mechanism. _Mol. Pharmacol._ 71, 835–842 (2007) . Article

CAS Google Scholar * Cremona, M. L. et al. Flotillin-1 is essential for PKC-triggered endocytosis and membrane microdomain localization of DAT. _Nat. Neurosci._ 14, 469–477 (2011) .

Article CAS Google Scholar * Adkins, E. M. et al. Membrane mobility and microdomain association of the dopamine transporter studied with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. _Biochemistry_ 46, 10484–10497 (2007) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Sakrikar, D. et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder-derived

coding variation in the dopamine transporter disrupts microdomain targeting and trafficking regulation. _J. Neurosci._ 32, 5385–5397 (2012) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Kahlig, K. M.

& Galli, A. Regulation of dopamine transporter function and plasma membrane expression by dopamine, amphetamine, and cocaine. _Eur. J. Pharmacol._ 479, 153–158 (2003) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Zahniser, N. R. & Sorkin, A. Rapid regulation of the dopamine transporter: role in stimulant addiction? _Neuropharmacology_ 47, (Suppl 1): 80–91 (2004) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Chi, L. & Reith, M. E. A. Substrate-induced trafficking of the dopamine transporter in heterologously expressing cells and in rat striatal synaptosomal preparations.

_J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther._ 307, 729–736 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Zahniser, N. R. & Sorkin, A. Trafficking of dopamine transporters in psychostimulant actions. _Semin.

Cell Dev. Biol._ 20, 411–417 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Saunders, C. et al. Amphetamine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and

cocaine-sensitive mechanism. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 97, 6850–6855 (2000) . Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Daws, L. C. et al. Cocaine increases dopamine uptake and cell surface

expression of dopamine transporters. _Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun._ 290, 1545–1550 (2002) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Woodward, J. J., Wilcox, R. E., Leslie, S. W. & Riffee, W.

H. Dopamine uptake during fast-phase endogenous dopamine release from mouse striatal synaptosomes. _Neurosci. Lett._ 71, 106–112 (1986) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Holz, R. W. &

Coyle, J. T. The effects of various salts, temperature, and the alkaloids veratridine and batrachotoxin on the uptake of [3H] dopamine into synaptosomes from rat striatum. _Mol. Pharmacol._

10, 746–758 (1974) . CAS Google Scholar * Sorkina, T., Richards, T. L., Rao, A., Zahniser, N. R. & Sorkin, A. Negative regulation of dopamine transporter endocytosis by

membrane-proximal N-terminal residues. _J. Neurosci._ 29, 1361–1374 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar * La Sala, M. S. et al. Modulation of taste responsiveness by the satiation hormone

peptide YY. _FASEB J._ 27, 5022–5033 (2013) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Gabriel, L. R. et al. Dopamine transporter endocytic trafficking in striatal dopaminergic neurons: differential

dependence on dynamin and the actin cytoskeleton. _J. Neurosci._ 33, 17836–17846 (2013) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Cha, J. H. et al. Rhodamine-labeled

2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)tropane analogues as high-affinity fluorescent probes for the dopamine transporter.. _J. Med. Chem._ 48, 7513–7516 (2005) . Article CAS Google

Scholar * Eriksen, J. et al. Visualization of dopamine transporter trafficking in live neurons by use of fluorescent cocaine analogs. _J. Neurosci._ 29, 6794–6808 (2009) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Hong, W. C. & Amara, S. G. Differential targeting of the dopamine transporter to recycling or degradative pathways during amphetamine- or PKC-regulated endocytosis in

dopamine neurons. _FASEB J._ 27, 1–13 (2013) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Eriksen, J., Bjørn-Yoshimoto, W. E., Jørgensen, T. N., Newman, A. H. & Gether, U. Postendocytic sorting of

constitutively internalized dopamine transporter in cell lines and dopaminergic neurons. _J. Biol. Chem._ 285, 27289–27301 (2010) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Rao, A., Simmons, D. &

Sorkin, A. Differential subcellular distribution of endosomal compartments and the dopamine transporter in dopaminergic neurons. _Mol. Cell Neurosci._ 46, 148–158 (2011) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Mattis, J. et al. Principles for applying optogenetic tools derived from direct comparative analysis of microbial opsins. _Nat. Methods_ 9, 159–172 (2012) . Article CAS

Google Scholar * Furman, C. A. et al. Dopamine and amphetamine rapidly increase dopamine transporter trafficking to the surface: live-cell imaging using total internal reflection

fluorescence microscopy. _J. Neurosci._ 29, 3328–3336 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Grant, B. D. & Donaldson, J. G. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. _Nat. Rev.

Mol. Cell Biol._ 10, 597–608 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Meiergerd, S. M., Patterson, T. A. & Schenk, J. O. D2 receptors may modulate the function of the striatal

transporter for dopamine: kinetic evidence from studies _in vitro_ and _in vivo_. _J. Neurochem._ 61, 764–767 (1993) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Prasad, B. M. & Amara, S. G. The

dopamine transporter in mesencephalic cultures is refractory to physiological changes in membrane voltage. _J. Neurosci._ 21, 7561–7567 (2001) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Kalivas, P.

W. Neurobiology of cocaine addiction: implications for new pharmacotherapy. _Am. J. Addict._ 16, 71–78 (2007) . Article Google Scholar * Vernier, P. et al. The degeneration of dopamine

neurons in Parkinson’s disease: insights from embryology and evolution of the mesostriatocortical system. _Ann. N Y Acad. Sci._ 1035, 231–249 (2004) . Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Kurian, M. A. et al. Clinical and molecular characterisation of hereditary dopamine transporter deficiency syndrome: an observational cohort and experimental study. _Lancet Neurol._ 10,

54–62 (2011) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Hansen, F. H. et al. Missense dopamine transporter mutations associate with adult parkinsonism and ADHD. _J. Clin. Invest._ 124, 3107–3120

(2014) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Lodge, D. J. & Grace, A. A. Developmental pathology, dopamine, stress and schizophrenia. _Int. J. Dev. Neurosci._ 29, 207–213 (2011) . Article

CAS Google Scholar * Cordeiro, Q., Siqueira-Roberto, J. & Vallada, H. Association between the SLC6A3 A1343G polymorphism and schizophrenia. _Arq. Neuropsiquiatr._ 68, 716–719 (2010) .

Article Google Scholar * Madras, B. K., Miller, G. M. & Fischman, A. J. The dopamine transporter: relevance to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). _Behav. Brain Res._ 130,

57–63 (2002) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Hastrup, H., Karlin, A. & Javitch, J. A. Symmetrical dimer of the human dopamine transporter revealed by cross-linking Cys-306 at the

extracellular end of the sixth transmembrane segment. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 98, 10055–10060 (2001) . Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hastrup, H., Sen, N. & Javitch, J. A. The

human dopamine transporter forms a tetramer in the plasma membrane: cross-linking of a cysteine in the fourth transmembrane segment is sensitive to cocaine analogs. _J. Biol. Chem._ 278,

45045–45048 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Kahlig, K. M., Javitch, J. A. & Galli, A. Amphetamine regulation of dopamine transport. Combined measurements of transporter currents

and transporter imaging support the endocytosis of an active carrier. _J. Biol. Chem._ 279, 8966–8975 (2004) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Goodwin, J. S. et al. Amphetamine and

methamphetamine differentially affect dopamine transporters _in vitro_ and _in vivo_. _J. Biol. Chem._ 284, 2978–2989 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Eshleman, A. J., Henningsen, R.

A., Neve, K. A. & Janowsky, A. Release of dopamine via the human transporter. _Mol. Pharmacol._ 45, 312–316 (1994) . CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Saha, K. et al. Intracellular

methamphetamine prevents the dopamine-induced enhancement of neuronal firing. _J. Biol. Chem._ 289, 22246–22257 (2014) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Fog, J. U. et al. Calmodulin kinase

II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. _Neuron_ 51, 417–429 (2006) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Sorkina, T., Doolen,

S., Galperin, E., Zahniser, N. R. & Sorkin, A. Oligomerization of dopamine transporters visualized in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. _J. Biol. Chem._

278, 28274–28283 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Miranda, M., Wu, C. C., Sorkina, T., Korstjens, D. R. & Sorkin, A. Enhanced ubiquitylation and accelerated degradation of the

dopamine transporter mediated by protein kinase C. _J. Biol. Chem._ 280, 35617–35624 (2005) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Choudhury, A. et al. Rab proteins mediate Golgi transport of

caveola-internalized glycosphingolipids and correct lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick C cells. _J. Clin. Invest._ 109, 1541–1550 (2002) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Navaroli, D. M. et

al. Rabenosyn-5 defines the fate of the transferrin receptor following clathrin-mediated endocytosis. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 109, E471–E480 (2012) . Article CAS Google Scholar *

Shen, K. & Meyer, T. Dynamic control of CaMKII translocation and localization in hippocampal neurons by NMDA receptor stimulation. _Science_ 284, 162–166 (1999) . Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Subach, F. V. et al. Photoactivatable mCherry for high-resolution two-color fluorescence microscopy. _Nat. Methods_ 6, 153–159 (2009) . Article CAS Google Scholar *

Zhang, F. et al. The microbial opsin family of optogenetic tools. _Cell_ 147, 1446–1457 (2011) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Rickhag, M. et al. Membrane permeable C-terminal dopamine

transporter peptides attenuate amphetamine-evoked dopamine release. _J. Biol. Chem._ 288, 27534–27544 (2013) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Kahlig, K. M. et al. Regulation of dopamine

transporter trafficking by intracellular amphetamine. _Mol. Pharmacol._ 70, 542–548 (2006) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Dahal, R. A. et al. Computational and biochemical docking of the

irreversible cocaine analog RTI 82 directly demonstrates ligand positioning in the dopamine transporter central substrate-binding site. _J. Biol. Chem._ 289, 29712–29727 (2014) . Article

CAS Google Scholar * Felts, B. et al. The two Na+ sites in the human serotonin transporter play distinct roles in the ion coupling and electrogenicity of transport. _J. Biol. Chem._ 289,

1825–1840 (2014) . Article CAS Google Scholar * Foster, J. D., Pananusorn, B., Cervinski, M. A., Holden, H. E. & Vaughan, R. A. Dopamine transporters are dephosphorylated in striatal

homogenates and _in vitro_ by protein phosphatase 1. _Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res._ 110, 100–108 (2003) . Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Dr Min Lin

for assistance and direction in preparation of midbrain neuron primary culture and Sean Olson for his assistance in preparing plasmid DNA. This study was funded by NIH grant # DA026947,

NS071122, OD020026 and the NIDA-IRP. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Ben D. Richardson and Kaustuv Saha: These authors contributed equally to this work AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Department of Neuroscience, Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, 32610, Florida, USA Ben D. Richardson, Kaustuv Saha, Elizabeth Cabrera,

Jarod Swant & Habibeh Khoshbouei * Department of Basic Sciences, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Grand Forks, 58203, North Dakota, USA Danielle Krout,

Bruce Felts & L. Keith Henry * Medicinal Chemistry Section, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, 21224, Maryland, USA Mu-Fa Zou & Amy Hauck

Newman Authors * Ben D. Richardson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kaustuv Saha View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Danielle Krout View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Elizabeth Cabrera View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bruce Felts View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * L. Keith Henry View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jarod Swant View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mu-Fa Zou View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Amy Hauck Newman View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Habibeh

Khoshbouei View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS B.D.R. and K.S. performed TIRF and electrophysiology experiments, and B.D.R.,

K.S. and E.C. performed confocal microscopy experiments, with guidance from H.K. M.-F.Z. and A.H.N. Biochemical experiments were performed by D.K. and B.F. under guidance from L.K.H.

Analysis was performed by B.D.R. and D.K. The project was initiated by H.K., B.D.R. and J.S. Together, B.D.R., K.S., L.K.H. and H.K. designed experiments. B.D.R. and H.K. wrote the

manuscript with significant input from L.K.H, D.K. and A.H.N. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Habibeh Khoshbouei. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing financial interests. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Methods. (PDF 915 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 1 Temporally

compressed TIRFM imaging sequences of HEK YFP-DAT cells during the bath perfusion of depolarizing 100mM KCl. Note rapid loss of YFP-DAT signal on the basal surface and edges at 0:01sec and

subsequently return at 0:03sec. (AVI 42799 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 2 Temporally compressed TIRFM imaging sequences of primary cultured neuron soma expressing RFP-DAT before and during

application of depolarizing 100mM KCl. Note rapid loss of RFP-DAT signal on the basal surface beginning at 0:03sec. (AVI 33424 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 3 Temporally compressed TIRFM imaging

sequences of primary cultured neuron soma expressing CFP-DAT before, during and after activation of archaerhodopsin with 590nm light between frames. Note steady increase in RFP-DAT signal

beginning at 0:01sec and gradual reduction beginning at 0:03sec, in line with photo-stimulation duration. (AVI 65847 kb) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the

credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of

this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Richardson, B., Saha, K., Krout, D. _et al._ Membrane potential

shapes regulation of dopamine transporter trafficking at the plasma membrane. _Nat Commun_ 7, 10423 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10423 Download citation * Received: 18 May 2015 *

Accepted: 09 December 2015 * Published: 25 January 2016 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10423 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative