‘Traffic-light’ nutrition labelling and ‘junk-food’ tax: a modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity prevention

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

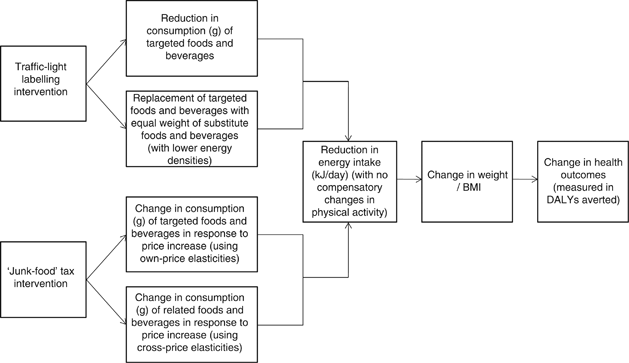

Cost-effectiveness analyses are important tools in efforts to prioritise interventions for obesity prevention. Modelling facilitates evaluation of multiple scenarios with varying

assumptions. This study compares the cost-effectiveness of conservative scenarios for two commonly proposed policy-based interventions: front-of-pack ‘traffic-light’ nutrition labelling

(traffic-light labelling) and a tax on unhealthy foods (‘junk-food’ tax).

For traffic-light labelling, estimates of changes in energy intake were based on an assumed 10% shift in consumption towards healthier options in four food categories (breakfast cereals,

pastries, sausages and preprepared meals) in 10% of adults. For the ‘junk-food’ tax, price elasticities were used to estimate a change in energy intake in response to a 10% price increase in

seven food categories (including soft drinks, confectionery and snack foods). Changes in population weight and body mass index by sex were then estimated based on these changes in

population energy intake, along with subsequent impacts on disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Associated resource use was measured and costed using pathway analysis, based on a health

sector perspective (with some industry costs included). Costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3%. The cost-effectiveness of each intervention was modelled for the 2003 Australian

adult population.

Both interventions resulted in reduced mean weight (traffic-light labelling: 1.3 kg (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 1.2; 1.4); ‘junk-food’ tax: 1.6 kg (95% UI: 1.5; 1.7)); and DALYs averted

(traffic-light labelling: 45 100 (95% UI: 37 700; 60 100); ‘junk-food’ tax: 559 000 (95% UI: 459 500; 676 000)). Cost outlays were AUD81 million (95% UI: 44.7; 108.0) for traffic-light

labelling and AUD18 million (95% UI: 14.4; 21.6) for ‘junk-food’ tax. Cost-effectiveness analysis showed both interventions were ‘dominant’ (effective and cost-saving).

Policy-based population-wide interventions such as traffic-light nutrition labelling and taxes on unhealthy foods are likely to offer excellent ‘value for money’ as obesity prevention

measures.

The ACE-Prevention project was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Health Services Research Grant (no. 351558). G Sacks is supported by a Deakin University

Postgraduate Research Scholarship. Jan Barendregt and Megan Forster played crucial roles in the development of the BMI to DALYs model. The authors are grateful to Theo Vos, Rob Carter and

Anne Magnus for their support in conducting this study.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention, Deakin University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

School of Population Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Deakin Health Economics, Deakin University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: