The influence of aging on the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Primary aldosteronism (PA) is common in young or middle-aged hypertensive patients, but PA among the elderly has recently become more common. As salt sensitivity increases with age,

plasma renin activity (PRA) tends to decrease, whereas the aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) tends to increase in the elderly. The aim of this study was to clarify the influence of aging on

the diagnosis of PA. We retrospectively evaluated 155 consecutively admitted patients who were not taking antihypertensive medications or calcium channel blockers and α blockers that

underwent PRA and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) measurements. The study subjects included 13 PA and 69 essential hypertensive (EHT) patients aged over 65 years, and 32 PA and 41 EHT

patients under aged 65 years. Our study clarified the influence of aging through screening and confirmatory tests for the diagnosis of PA. Our results showed the ARR cutoff value for a

screening test to be 556 (area under the curve: AUC=0.906), its sensitivity and specificity to be 84.6% and 89.9%, respectively, and the likelihood ratio to be 8.34 in the elderly, whereas

the ARR cutoff value was 272 in the non-elderly. In the saline infusion test, the mean PAC was 86.6±41.8 pg ml−1 in the elderly and 158.1±116.5 pg ml−1 in the non-elderly (_P_=0.04). There

was no influence from age in both the captopril challenge test and the furosemide upright test. Aging may influence PA screening and saline infusion tests; thus, we should consider the

influence of aging in the diagnosis of elderly subjects with PA. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PRIMARY ALDOSTERONISM IN ELDERLY, OLD, AND VERY OLD PATIENTS Article 14 September 2020

ALDOSTERONE-TO-RENIN RATIO IS RELATED TO ARTERIAL STIFFNESS WHEN THE SCREENING CRITERIA OF PRIMARY ALDOSTERONISM ARE NOT MET Article Open access 13 November 2020 SIMPLE STANDING TEST

WITHOUT FUROSEMIDE IS USEFUL IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF PRIMARY ALDOSTERONISM Article Open access 17 August 2023 INTRODUCTION Primary aldosteronism (PA) is one of the most common forms of secondary

hypertension and may account for as much as 5–10% of patients with hypertension.1, 2, 3, 4 The main presentations of PA are aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) and idiopathic

hyperaldosteronism. APA is generally curable by surgical treatment, whereas idiopathic hyperaldosteronism is mainly treated through aldosterone blockade.5, 6 Aldosterone is an adrenal

hormone that regulates sodium and fluid retention. Because, in addition to these genomic effects, it has been demonstrated that aldosterone might induce inflammation and fibrotic changes in

end organs such as the heart, kidney, blood vessels and brain, a high aldosterone state is believed to be one of the causes of high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, coronary artery

disease, chronic kidney disease and metabolic syndrome.7, 8, 9 Several studies have reported a high incidence of cardiovascular complications in patients with PA compared with patients with

essential hypertension (EHT).10, 11 Therefore, the early diagnosis of PA and treatment planning are necessary to prevent the progression of cardiovascular complications.12, 13 However, the

diagnosis of PA is sometimes difficult and consists of three processes: screening, confirmatory tests and imaging tests.14 The World Health Organization defines people over the age of 65

years as elderly. The Japanese Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry further defines those between 65 and 74 years as young-old and those over 75 years as old-old. This definition is especially

important for the Japanese medical insurance and long-term care insurance sectors, as the increasing costs of medical insurance is a serious issue in Japan. Recently, the number of elderly

patients has increased, mainly in developed countries; therefore, elderly PA is becoming more common in patients with refractory hypertension,15 although PA is generally thought to be common

in young or middle-aged hypertensive patients. As salt sensitivity increases with aging, both the plasma renin activity (PRA) and aldosterone concentration (PAC) tend to be low, and,

consequently, the aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) increases in the elderly.16 However, there have been limited studies that have evaluated the influence of aging on the diagnostic

procedures for PA.17 In the present study, we investigated the influence of aging on the screening and confirmatory tests used for PA diagnosis to improve the accuracy of PA diagnosis in

patients with hypertension. We also clarify the ARR cutoff value for PA diagnosis in elderly patients with hypertension from a medical economic perspective in an effort to reduce the medical

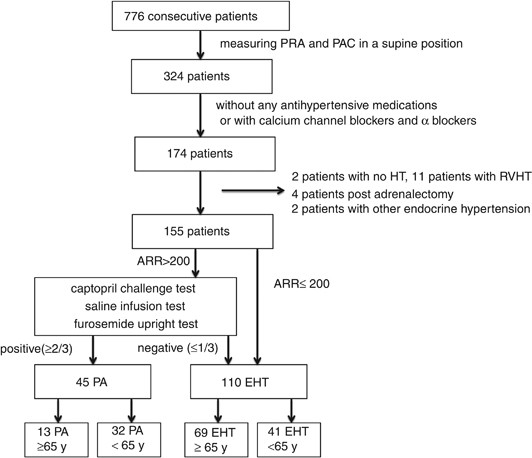

insurance costs. METHODS Figure 1 presents the process of subject recruitment. Seven hundred and seventy-six consecutive patients were admitted to the Department of Geriatric Medicine and

Hypertension at Osaka University Hospital from April 1, 2009 to May 31, 2012. Three hundred and twenty-four patients underwent PRA and PAC measurements, and 174 out of the 324 patients were

not taking any antihypertensive medications or were only on calcium channel blockers or α blockers for at least 2 weeks. We excluded 2 patients without high blood pressure, 11 patients with

renovascular hypertension, 4 patients post-adrenalectomy and 2 patients with other forms of endocrine hypertension, leaving us with 155 patients who were evaluated for this study. PRA and

PAC were determined by radioimmunoassay. All patients had mild-to-severe hypertension, and blood samples were obtained after the patient was in the supine position for over 30 min. The mean

salt intake calculated by food was 9.5±1.2 g, which was similar to the average Japanese salt intake. For subjects with an ARR over 200, we performed three confirmatory tests (captopril

challenge test, saline infusion test and furosemide upright test) according to Japanese guidelines.18, 19 In the captopril challenge test, patients received 50 mg of captopril orally after

being in a recumbent position for 30 min. Blood samples for the measurements of PRA, PAC and ARR were drawn at 0, 60 and 90 min after drug administration, respectively, and subjects with an

ARR ⩾200 at 60 or 90 min after drug administration were considered to be positive for PA. In the saline infusion test, patients remained in the supine position for 30 min before and during

the infusion of 2 l of saline over 4 h. Blood samples for the measurement of PRA, PAC and ARR were drawn at time 0 and after 4 h, and subjects with a high PAC (>60 pg ml−1) at 4 h after

saline infusion were considered to be positive for PA. In the furosemide upright test, patients were intravenously administered 40 mg furosemide after remaining in a recumbent position for

30 min and then maintained at an upright posture for 2 h. Blood samples for the measurements of PRA, PAC and ARR were drawn at time 0 and after 2 h, and subjects with a low PRA (<2.0 ng

ml−1 h−1) at 2 h after furosemide injection were considered to be PA-positive. All tests started at 0800–0900 hours local time. If subjects tested positive for more than two-thirds of the

confirmatory tests, we diagnosed them with PA according to the guidelines for the detection of PA from the Japan Endocrine Society.18 We categorized patients over 65 years to be in the

elderly group and placed those under 65 years in the non-elderly group. Sixty-three patients (20 elderly, 43 non-elderly) with an ARR >200 underwent confirmatory tests, and of those, 45

patients (13 elderly, 32 non-elderly) received a diagnosis of PA. Then, patients were divided into 13 PA and 69 EHT patients in the elderly and 32 PA and 41 EHT patients in the non-elderly.

In the elderly PA group, six patients received adrenal vein sampling (AVS), and four out of the six patients were diagnosed with APA. Three patients received adrenalectomies, and all of them

were diagnosed with APA through pathology. In the non-elderly PA group, 24 patients had AVS, and 14 of them were diagnosed with APA. Seven patients had adrenalectomies and were diagnosed

with APA through pathology (Table 1). We compared each clinical background factor and identified a cutoff value of ARR in the elderly and non-elderly subjects from an receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve. We also compared the elderly with non-elderly PA patients in the confirmatory tests. We excluded 2 PA patients who received confirmatory tests and were diagnosed

after the study period, and finally analyzed 13 elderly and 30 non-elderly PA patients. All data are expressed as the mean±s.d. Differences between the groups were assessed using the

chi-square analysis and _t_ test, as appropriate. ROC analyses were used to determine the cutoff value of PRA, PAC and ARR. _P_<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All

statistical analyses were performed with the JMP Software, Version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). RESULTS The demographics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. Among the

elderly patient group, the average age was 71.5±4.4 years for PA patients and 73.4±6.0 years for EHT patients (N.S.). In the non-elderly patient group, the average age was 46.8±10.7 years

for PA patients and 50.0±11.5 years for EHT patients (N.S.). Sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c and salt intake were not significantly different among each subject group.

Diastolic blood pressure in the elderly was significantly lower than in the non-elderly, and diastolic blood pressure in the non-elderly EHT group was also significantly higher than in the

non-elderly PA group. The mean PRA was significantly lower and the mean PAC was significantly higher in the elderly PA patients than in the elderly EHT patients (_P_<0.05, _P_<0.001,

respectively), and in the non-elderly subjects the mean PRA was significantly lower in PA patients than in EHT patients (_P_<0.001); however, there were no significant differences in the

mean PAC. ARR was significantly higher in PA compared with EHT in both the elderly and non-elderly (_P_<0.0001). Among the elderly, the average serum K level was significantly lower in PA

patients than in EHT patients (_P_=0.044), but there were no significant differences in serum K level in the non-elderly subjects. Among EHT patients, the PAC was significantly lower and

the serum K value was significantly higher in the elderly than in the non-elderly patients (_P_<0.01, _P_<0.05, respectively). The distribution of ARR in patients with PA and EHT in

the elderly and non-elderly subjects is shown in Figure 2a. The range of ARR among elderly EHT patients is much wider than that among non-elderly EHT patients. The ARR, PAC and PRA were

further compared to distinguish between PA and EHT using ROC curves. When the ARR cutoff value was 556 (area under the curve: AUC=0.906) in the elderly subjects, its sensitivity, specificity

and the likelihood ratio of a positive test were 84.6, 89.9 and 8.34, respectively (Figure 2b). In the elderly, its sensitivity and specificity were 84.6 and 50.7% when the PAC cutoff value

was 110 pg ml−1 (AUC=0.706), and its sensitivity and specificity were 100 and 59.4% when the PRA cutoff value was 0.6 ng ml−1 h−1 (AUC=0.836) (Figures 2d and f). The AUC of ARR was

significantly higher than that of PAC and PRA in the elderly (_P_=0.018, _P_=0.021, respectively). When the ARR cutoff value was 272 (AUC=0.958) in the non-elderly subjects, its sensitivity,

specificity and the likelihood ratio of a positive test were 96.9%, 85.4% and 6.62, respectively (Figure 2c). In the non-elderly, its sensitivity and specificity were 96.9 and 31.7% when

the PAC cutoff value was 116 pg ml−1 (AUC=0.613), and its sensitivity and specificity were 81.3 and 82.9% when the PRA cutoff value was 0.4 ng ml−1 h−1 (AUC=0.908) (Figures 2e and g). The

AUC of ARR was significantly higher than that of PAC and PRA in the non-elderly (_P_<0.001, _P_=0.029, respectively). In the present study, we compared elderly with non-elderly PA

patients in three confirmatory tests: the captopril challenge test, the saline infusion test and the furosemide upright test. The captopril challenge test was performed in 58 subjects (42

PA, 16 EHT). Forty-six patients (39 PA and 7 EHT) showed a positive test result, and sensitivity and specificity were 92.9% and 56.3%, respectively. We divided subjects who received the

captopril challenge test into 13 elderly PA, 29 non-elderly PA, 10 elderly EHT and 6 non-elderly EHT patients. There were no significant differences in the mean ARR 60 and 90 min after

taking captopril (Table 2). On ROC curves of ARR 60 and 90 min after taking captopril, the cutoff value of ARR was 260 after 60 min (AUC=0.735, sensitivity=84.6%, specificity=66.7%) and 306

after 90 min (AUC=0.685, sensitivity=75.0%, specificity=66.7%) in the elderly patients. The cutoff value of ARR was 198 after 60 min (AUC=0.874, sensitivity=93.1%, specificity=66.7%) and 213

after 90 min (AUC=0.867, sensitivity=88.0%, specificity=83.3%) in the non-elderly patients. Fifty-seven HT patients (40 PA, 17 EHT) underwent a saline infusion test, and 37 patients (34 PA

and 3 EHT) were positive, with the sensitivity and specificity reported as 85.0% and 82.4%, respectively. We divided subjects who received the saline infusion test into 13 elderly PA, 27

non-elderly PA, 10 elderly EHT and 7 non-elderly EHT patients. The mean PAC before loading saline showed no significant difference among the elderly and non-elderly PA patient groups.

However, PAC after loading was significantly lower in the elderly PA patients than in the non-elderly PA group (_P_=0.04) (Table 3). On ROC curves of PAC after loading, the cutoff value of

PAC was 72 pg ml−1 (AUC=0.831, sensitivity=69.2%, specificity=100.0%) in the elderly patients, but was 70 pg ml−1 (AUC=0.862, sensitivity=88.9%, specificity=85.7%) in the non-elderly

patients. Forty-one HT patients (34 PA, 7 EHT) underwent the furosemide upright test and 37 patients (33 PA and 4 EHT) had a positive test result, with a sensitivity and specificity of 97.1%

and 42.9%, respectively. We divided subjects who received the furosemide upright test into 10 elderly PA, 24 non-elderly PA, 2 elderly EHT and 5 non-elderly EHT patients. There were no

significant differences in the mean PRA after injecting furosemide and standing (Table 4). On ROC curves of PRA, the cutoff value of PRA was 0.4 ng ml−1 h−1 (AUC=0.750, sensitivity=50.0%,

specificity=100.0%) in the elderly patients, but was 1.4 ng ml−1 h−1 (AUC=0.796, sensitivity=95.8%, specificity=60.0%) in the non-elderly patients. DISCUSSION In the present study, we

assessed the influence of age on the screening and confirmatory tests for the diagnosis of PA. We drew an ROC curve of ARR on the screening test considering the influence of age.

Consequently, the cutoff value of ARR was 556 in elderly subjects over 65 years and its sensitivity and specificity were 84.6% and 89.9%, respectively, whereas the cutoff value of ARR was

272 in non-elderly subjects under 65 years and its sensitivity and specificity were 96.9% and 85.4%, respectively. In addition, the AUC of ARR was the highest among the three indexes (ARR,

PAC and PRA) and the cutoff value of ARR indicated the best sensitivity and specificity (Figure 2). The usefulness of ARR is emphasized, and has been recommended as the screening test for PA

in all age groups of patients with hypertension.20 The cutoff value of ARR has been reported to be 200–500,21, 22, 23 and a value >200–300 is recommended in guidelines.14, 18, 19 In the

present study, ARR was the best index for the screening test for PA diagnosis, and the cutoff value of ARR in non-elderly patients was 272, supporting previous reports.21, 22, 23 However,

there are few reports on the best value for PA screening in the elderly. Salt sensitivity increases with age and PRA tends to be low while ARR increases in the elderly.16 Our study suggested

that ARR is superior to only PRA or PAC as a screening test for PA diagnosis even in elderly patients, and ARR criteria in the elderly may need to be much higher than in the non-elderly. In

confirmatory tests, it is also expected that salt sensitivity will influence these results in elderly subjects. The PAC of the elderly after saline loading was significantly lower than that

of the non-elderly. This outcome suggested that PAC could easily be used to determine a negative test result among elderly PA patients for the saline infusion test. However, there were no

significant differences between the elderly and non-elderly subjects both in the captopril challenge test and furosemide upright test. This outcome may be because of the fact that the saline

infusion test only utilizes the PAC value to determine the test result. PRA and PAC are generally influenced by various conditions such as blood sampling at outpatient clinics or hospitals,

posture, time of day, and water, sodium and potassium intakes. It has been reported that PAC tends to be lower in blood samples from outpatients compared with those collected during

hospitalization, whereas no significant change has been reported for ARR.20, 24 For all study subjects, PRA, PAC and ARR were measured in the supine position 30 min after resting on the

morning of the screening test for PA diagnosis. We examined the effect of age under the same conditions to the extent possible. Performing a confirmatory test is an important step after the

screening test for PA diagnosis. It is necessary to verify the autonomous secretion of aldosterone for the diagnosis of PA. Japanese guidelines18, 19 recommend performing one or two

confirmatory tests out of the captopril challenge test, saline infusion test and furosemide upright test. The captopril challenge test,25, 26, 27 saline infusion test,22, 28, 29, 30

furosemide upright test,31, 32 oral salt loading test23 and fludrocortisone suppression test30 are generally performed in Japan and other countries; however, the drug doses, posture during

testing and criteria for determining a positive test result are not uniform. We performed the captopril challenge, saline infusion and furosemide upright tests according to the protocol and

criteria from The Japan Endocrine Society.18 If a patient had more than two positive confirmatory tests, they were diagnosed with PA. Therefore, we chose to investigate the influence of age

on these three confirmatory tests. As elderly patients often have reduced cardiac function or other organ damage, confirmatory tests and AVS may cause more complications than in non-elderly

patients. If the cutoff value of ARR in the elderly is 200–300 as in the non-elderly subjects, or we interpret the results of the saline infusion test using the same criteria as for

non-elderly people, many elderly subjects with hypertension may receive unnecessary confirmatory tests or AVS. Furthermore, confirmatory tests and AVS are usually performed upon hospital

admission and are costly. Therefore, patients targeted for confirmatory tests and AVS should be selected carefully, especially in elderly subjects. In our study, the prevalence of PA was

much higher than in previous reports1, 2, 3, 4 because our study excluded patients who tested negatively for PA in the screening test and were taking angiotensin converting enzyme

inhibitors, AT1 receptor antagonists or β blockers. Additionally, subjects consisted of patients who were suspected of having PA and were referred to our department. The effects of

antihypertensive agents on PRA and PAC should be taken into account for the screening and confirmatory tests of PA. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, AT1 receptor antagonists and

calcium channel blockers decrease PAC and increase PRA, and β blockers and α blockers decrease both PRA and PAC. However, calcium channel blockers and α blockers have less of an effect on

the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.33, 34 Therefore, previous Japanese guidelines have recommended that antihypertensive drugs other than calcium channel blockers and α blockers cease

prior to measuring PRA and PAC.18, 19 Thus, the subjects in the present study either took no medication or took only calcium channel blockers and α blockers. Our study has some limitations.

Only13 elderly patients received a diagnosis of PA. As only 66.7% of PA patients received AVS, none of the study subjects had detailed diagnoses, such as the type of PA. We performed three

confirmatory tests and made a diagnosis of PA when more than two-thirds of the tests were positive; however, no HT patients whose ARR was over 200 received all three confirmatory tests. Some

elderly patients did not receive the furosemide upright test because of hypotension during testing or weakness of the legs. In conclusion, our study suggests that in the elderly, the ARR

criteria for the screening test of PA diagnosis may be set up at a much higher level than in the non-elderly, and ARR is useful as a PA screening test even in elderly patients with

hypertension. In confirmatory tests, the saline infusion test but not the captopril challenge test or the furosemide upright test may be significantly influenced by aging because of low PAC

level in the elderly. The incidence of cardiovascular complications is higher in PA than in EHT, and recent studies have indicated that aldosterone induces congestive heart failure, coronary

artery disease, chronic kidney disease and metabolic syndrome;7, 8, 9 therefore, the diagnosis of PA is becoming more important. Now, opportunities to perform the diagnostic tests for PA

are becoming more common for elderly hypertensive patients. As aging influences the screening and saline infusion test, on the basis of our present study, we should be careful with

diagnostic tests for PA in the elderly. REFERENCES * Gordon RD, Stowasser M, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Rutherford JC . High incidence of primary aldosteronism in 199 patients referred with

hypertension. _Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol_ 1994; 21: 315–318. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lim PO, Dow E, Brennan G, Jung RT, MacDonald TM . High prevalence of primary

aldosteronism in the Tayside hypertension clinic population. _J Hum Hypertens_ 2000; 14: 311–315. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T

. Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. _Hypertens Res_ 2004; 27: 193–202. Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, Desideri G, Fabris B, Ferri C, Ganzaroli C, Giacchetti G, Letizia C, Maccario M, Mallamaci F, Mannelli M, Mattarello MJ, Moretti A,

Palumbo G, Parenti G, Porteri E, Semplicini A, Rizzoni D, Rossi E, Boscaro M, Pessina AC, Mantero F . A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive

patients. _J Am Coll Cardiol_ 2006; 48: 2293–2300. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Conn JW . Primary aldosteronism, a new clinical syndrome. _J Lab Clin Med_ 1955; 45: 6–17. Google

Scholar * Brown JJ, Davies DL, Ferriss JB, Fraser R, Haywood E, Lever AF, Robertson JI . Comparison of surgery and prolonged spironolactone therapy in patients with hypertension,

aldosterone excess, and low plasma renin. _Br Med J_ 1972; 2: 729–734. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Brilla CG, Weber KT . Mineralocorticoid excess, dietary sodium,

and myocardial fibrosis. _J Lab Clin Med_ 1992; 120: 893–901. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Blasi ER, Rocha R, Rudolph AE, Blomme EA, Polly ML, McMahon EG . Aldosterone/salt induces renal

inflammation and fibrosis in hypertensive rats. _Kidney Int_ 2003; 63: 1791–1800. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hannemann A, Meisinger C, Bidlingmaier M, Döring A, Thorand B, Heier

M, Belcredi P, Ladwig KH, Wallaschofski H, Friedrich N, Schipf S, Lüdemann J, Rettig R, Peters J, Völzke H, Seissler J, Beuschlein F, Nauck M, Reincke M . Association of plasma aldosterone

with the metabolic syndrome in two German populations. _Eur J Endocrinol_ 2011; 164: 751–758. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Savard S, Amar L, Plouin PF, Steichen O . Cardiovascular

complications associated with primary aldosteronism: a controlled cross-sectional study. _Hypertension_ 2013; 62: 331–336. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mulatero P, Monticone S,

Bertello C, Viola A, Tizzani D, Iannaccone A, Crudo V, Burrello J, Milan A, Rabbia F, Veglio F . Long-term cardio- and cerebrovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. _J Clin

Endocrinol Metab_ 2013; 98: 4826–4833. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Catena C, Colussi G, Lapenna R, Nadalini E, Chiuch A, Gianfagna P, Sechi LA . Long-term cardiac effects of

adrenalectomy or mineralocorticoid antagonists in patients with primary aldosteronism. _Hypertension_ 2007; 50: 911–918. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ,

Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J . The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study

Investigators. _N Engl J Med_ 1999; 341: 709–717. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Funder JW, Carey RM, Fardella C, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Mantero F, Stowasser M, Young WF Jr, Montori VM .

Case detection, diagnosis and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. _J Clin Endocrinol Metab_ 2008; 93: 3266–3281. Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Fujii H, Kamide K, Miyake O, Abe T, Nagai M, Nakahama H, Horio T, Takiuchi S, Okuyama A, Yutani C, Kawano Y . Primary aldosteronism combined with preclinical

Cushing's syndrome in an elderly patient. _Circ J_ 2005; 69: 1425–1427. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Olivieri O, Ciacciarelli A, Signorelli D, Pizzolo F, Guarini P, Pavan C,

Corgnati A, Falcone S, Corrocher R, Micchi A, Cressoni C, Blengio G . Aldosterone to Renin ratio in a primary care setting: the Bussolengo study. _J Clin Endocrinol Metab_ 2004; 89:

4221–4226. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yin G, Zhang S, Yan L, Wu M, Xu M, Li F, Cheng H . Effect of age on aldosterone/renin ratio (ARR) and comparison of screening accuracy of

ARR plus elevated serum aldosterone concentration for primary aldosteronism screening in different age groups. _Endocrine_ 2012; 42: 182–189. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Nishikawa T, Omura M, Satoh F, Shibata H, Takahashi K, Tamura N, Tanabe A, Task Force Committee on Primary Aldosteronism, The Japan Endocrine Society. Guidelines for the diagnosis and

treatment of primary aldosteronism–the Japan Endocrine Society 2009. _Endocr J_ 2011; 58: 711–721. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki

J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S,

Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H, Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for

the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). _Hypertens Res_ 2009; 32: 3–107. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hiramatsu K, Yamada T, Yukimura Y, Komiya I, Ichikawa K, Ishihara M, Nagata H,

Izumiyama T . A screening test to identify aldosterone producing adenoma by measuring plasma renin activity. Results in hypertensive patients. _Arch Intern Med_ 1981; 141: 1589–1593. Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Loh KC, Koay ES, Khaw MC, Emmanuel SC, Young WF Jr . Prevalence of primary aldosteronism among Asian hypertensive patients in Singapore. _J Clin Endocrinol

Metab_ 2000; 85: 2854–2859. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Strauch B, Zelinka T, Hampf M, Bernhardt R, Widimsky J Jr . Prevalence of primary hyperaldosteronism in moderate to severe

hypertension in the Central Europe region. _J Hum Hypertension_ 2003; 17: 349–352. Article CAS Google Scholar * Williams JS, Williams GH, Raji A, Jeunemaitre X, Brown NJ, Hopkins PN,

Conlin PR . Prevalence of primary hyperaldosteronism in mild to moderate hypertension without hypokalemia. _J Hum Hypertens_ 2006; 20: 129–136. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tanabe

A, Naruse M, Takagi S, Tsuchiya K, Imaki T, Takano K . Variability in the renin/aldosterone profile under random and standardized sampling conditions in primary aldosteronism. _J Clin

Endocrinol Metab_ 2003; 88: 2489–2494. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Agharazii M, Douville P, Grose JH, Lebel M . Captopril suppression versus salt loading in confirming primary

aldosteronism. _Hypertension_ 2001; 37: 1440–1443. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rossi E, Regolisti G, Negro A, Sani C, Davoli S, Perazzoli F . High prevalence of primary

aldosteronism using postcaptopril plasma aldosterone to renin ratio as a screening test among Italian hypertensives. _Am J Hypertens_ 2002; 15: 896–902. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Castro OL, Yu X, Kem DC . Diagnostic value of the post captopril test in primary aldosteronism. _Hypertension_ 2002; 39: 935–938. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Giacchetti G,

Ronconi V, Lucarelli G, Boscaro M, Mantero F . Analysis of screening and confirmatory tests in the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism: need for a standardized protocol. _J Hypertens_ 2006;

24: 737–745. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Holland OB, Brown H, Kuhnert L, Fairchild C, Risk M, Gomez- Sanchez CE . Further evaluation of saline infusion for the diagnosis of

primary aldosteronism. _Hypertension_ 1984; 6: 717–723. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mulatero P, Milan A, Fallo F, Regolisti G, Pizzolo F, Fardella C, Mosso L, Marafetti L, Veglio

F, Maccario M . Comparison of confirmatory tests for the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism. _J Clin Endocrinol Metab_ 2006; 91: 2618–2623. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Omura M,

Nishikawa T . Screening tests and diagnostic examinations of hypertensives for primary aldosteronism. _Rinsho Byori_ 2006; 54: 1157–1163 (Japanese). PubMed Google Scholar * Nanba K,

Tamanaha T, Nakao K, Kawashima ST, Usui T, Tagami T, Okuno H, Shimatsu A, Suzuki T, Naruse M . Confirmatory testing in primary aldosteronism. _J Clin Endocrinol Metab_ 2012; 97: 1688–1694.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Seifarth C, Trenkel S, Schobel H, Hahn EG, Hensen J . Influence of antihypertensive medication on aldosterone and renin concentration in the

differential diagnosis of essential hypertension and primary aldosteronism. _Clin Endocrinol_ 2002; 57: 457–465. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rossi GP . A comprehensive review of the

clinical aspects of primary aldosteronism. _Nat Rev Endocrinol_ 2011; 7: 485–495. Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was supported by the

Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies through a research grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of

Geriatric Medicine and Nephrology, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan Chikako Nakama, Kei Kamide, Tatsuo Kawai, Kazuhiro Hongyo, Norihisa Ito, Miyuki Onishi, Yasushi

Takeya, Koichi Yamamoto, Ken Sugimoto & Hiromi Rakugi * Division of Health Sciences, Department of Health Promotion Science, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Japan

Kei Kamide Authors * Chikako Nakama View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kei Kamide View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tatsuo Kawai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kazuhiro Hongyo View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Norihisa Ito View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Miyuki Onishi View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yasushi Takeya View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Koichi Yamamoto View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ken Sugimoto View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hiromi

Rakugi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Kei Kamide. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no conflicts of interest. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Nakama, C., Kamide, K., Kawai, T. _et al._ The influence of

aging on the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism. _Hypertens Res_ 37, 1062–1067 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.129 Download citation * Received: 19 February 2014 * Revised: 27 June

2014 * Accepted: 07 July 2014 * Published: 28 August 2014 * Issue Date: December 2014 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.129 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * confirmatory test * diagnosis * elderly * primary aldosteronism * screening test