Do recorded abstracts from scientific meetings concur with the research presented?

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT PURPOSE Research abstracts for scientific meetings are usually submitted several months in advance of the meeting. Authors may therefore be tempted to submit an abstract on the

basis of the research that is ongoing or not yet fully analysed. This study aims to determine the extent to which submitted abstracts, often disseminated in printed form or online, differ

from the research ultimately presented. The risk taken by clinicians considering changes in practice on the basis of presented research who refer back to the printed abstract can be

assessed. METHODS All posters presented at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress 2007 were compared with abstracts in the ‘Final Programme and Abstracts’. Discrepancies were

recorded for authorship, title, methodology, number of cases, results and conclusions. RESULTS A total of 171 posters were examined. The title changed in 21% (36/171) and authorship in 25%.

The number of cases differed in 22% (number of cases in the poster ranging from less than one quarter to more than triple the number in the abstract). Differences between abstract and poster

were found in the methodology of 4%, the results of 11% and conclusions of 5% of studies. CONCLUSIONS Scientific meetings provide an opportunity for timely dissemination of new research

presented directly to clinicians who may then consider change of practice in response. Caution is advised when referring back to printed records of abstracts, as substantial discrepancies

are frequently seen between the published abstract and the final research presented, which, in a minority of cases, may even alter the conclusions of the research. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING

VIEWED BY OTHERS EXPLORING THE FRAGILITY OF META-ANALYSES IN OPHTHALMOLOGY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Article 20 July 2024 ANALYSIS OF RETRACTED ARTICLES IN THE OPHTHALMIC LITERATURE Article 16

February 2021 NON-INFERIORITY TRIALS IN CLINICAL OPHTHALMOLOGY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Article 01 May 2025 INTRODUCTION Scientific meetings provide an important forum for early dissemination of

ophthalmic research findings, either by podium presentation or by means of posters. The deadline for submission of abstracts is frequently several months in advance of the meeting itself.

The temptation therefore exists for authors to submit speculative abstracts on the basis of the findings of research that is still ongoing or has not yet been fully analysed. Such abstracts,

if accepted for presentation, are usually included in the printed programme that is distributed to delegates attending the meeting, and are also often made more widely available online,

such as at http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/scientific or http://www.arvo.org. The aim of this study is to determine the extent to which research ultimately presented in posters at a scientific

meeting differs from the disseminated abstract. Many previous studies have shown that, of studies initially presented as posters, typically around half will subsequently reach full

publication in the peer-reviewed literature.1 So long as clinicians are able to access these full published results, the risks associated with inaccurate abstracts are much diminished.

However, for the half of studies that remain unpublished, there is a risk that clinicians having seen the posters or presentation at a meeting may refer back to the printed abstract. No

previous study comparing the content of published abstracts to the actual research presented at scientific meetings was identified. Moreover, in addition to the possible clinical risk posed

by the submission of speculative abstracts on the basis of incomplete research, there is an issue of probity in research practice that should be considered. This study provides the first

evidence of the extent of the practice of authors changing the substance of their work after having an abstract accepted. MATERIALS AND METHODS All posters presented at the Royal College of

Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) Annual Congress 2007 were examined and compared with the abstracts in the ‘Final Programme and Abstracts’. Discrepancies between the poster and the abstract were

recorded with reference to authorship, title, methodology, number of cases, results and conclusions. Definitions of what constituted a discrepancy were constructed by the authors to reflect

the point at which such changes might constitute a problem for someone wishing to apply the findings to their own practice, evaluate the quality of the research or conduct electronic search

of the peer-reviewed literature to look for subsequent full publication. Change in authorship was recorded for addition, deletion or misspelling of names. Alteration of study title was

recorded, but a title was not considered to have changed when the alteration was merely in conjunctions, prepositions, punctuation or word order. As abstracts are limited to 250 words, no

change was recorded on the basis of an omission of details in the abstract. Changes in methodology were only recorded when there was an explicit difference in method between the abstract and

the poster, such as a clearly stated change in inclusion/exclusion criteria or in defined outcome measures. Sample size or numbers of cases reported were recorded and percentage changes

were calculated. Any discrepancy in the reported results was considered. When a change in sample size had occurred, a numerical change in any outcome measures was deemed a likely

consequence, although such changes in the numerical values _per se_ were not deemed significant. In these cases a discrepancy was only recorded if there was either a change in the direction

of the results or a move from significance to non-significance or vice versa. Discrepancies between the main conclusions of a study between abstract and poster presentation were recorded,

although the addition of subsidiary conclusions in a poster was not recorded as a change. Each author assessed half of the posters presented. Interobserver agreement was measured by

duplicate assessment of 20 posters; Cohen's Kappa was calculated by the VassarStats online statistics tool (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html). RESULTS At RCOphth

congress 2007 there were 170 abstracts accepted for presentation solely as posters. A further 29 abstracts were accepted for short oral presentation from the podium. The authors of 16 of

these 29 oral presentations also prepared posters for display and these were included in this study. No poster was displayed for 15 of the 170 accepted ‘poster only’ abstracts. Of the 171

posters therefore examined, 36 (21%) carried a title, which was changed from that published in the ‘Final Programme and Abstracts’. Authorship remained unchanged in 128 of the 171 (75%)

cases. In 30 posters, one or more authors were added (range 1–5) and in 12 cases one or more authors were removed from the abstract (range 1–2). There were 13 instances of differences in the

spelling of authors' surnames. Study design was not universally apparent from abstracts. The most frequently reported study designs were cross-sectional surveys 48/171 (28%) and case

series 43/171 (25%). In seven studies (4%), the method described on the poster was explicitly altered from that described in the abstract; for example, one study created a binary definition

of visual status denoted ‘better’ and ‘poor’, and thereby classified patients into one of these two groups at the point of presentation and then again after intervention. The criterion for

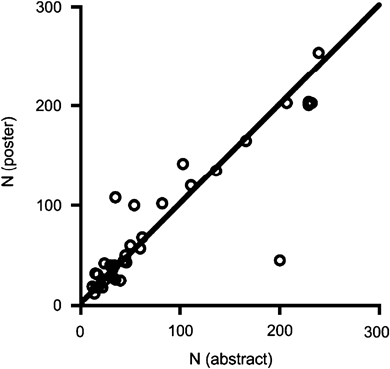

being assigned to the ‘better’ group was ⩾6/36 in the methods described in the abstract, but on the poster presented, a definition of ⩾6/18 had been adopted. In 38 studies (22%), the number

of cases differed between the abstract and poster (Figure 1). The percentage difference, taking the value of ‘_n_’ in the abstract as the reference value, ranged from 78% fewer cases on the

poster (a drop from 200 cases in the abstract to 45 on the poster) to 309% (an increase from 35 cases in the abstract to 108 on the poster) (Figure 2). Of the 133 posters in which no change

in sample size occurred, nine (7%) reported results that differed from those in the abstract. Of the 38 studies in which the number of cases changed, 13 (34%) reported results that fitted

the described definition for having changed; for example, one study of limbal-relaxing incisions reported in the abstract that ‘In a majority of patients, astigmatism continues to decline

several years after surgery’. However, the results presented in the congress poster show the opposite to be true, and the poster stated that ‘In a majority of patients…astigmatism remains

stable from 2 weeks after surgery to over 2 years later’. Only 5% of the studies (9/171) were found to have conclusions on abstract and poster that were totally different or directly

contradicted one another; for example, a study of cataract surgery complications associated with anti-platelet drugs reported in the printed abstract that ‘The haemorrhagic operative

complications of choroidal/supra-choroidal haemorrhage and hyphaema were more common in those on clopidogrel’, but on the poster presented it stated that ‘No increase in the rate of

haemorrhagic operative complications was found in any group’. Another study looking at exposure rates in different orbital implants concludes in the printed abstract that both the implants

in question ‘demonstrated excellent retention rates’, whereas on the presented poster, after more than tripling the sample size, the conclusion is drawn that ‘SST implants displayed higher

exposure rates with early development of large central defects’, with this type of implant being associated with more than double the exposure rate of the other. The Kappa statistic was 0.82

showing a good level of agreement between the observers. DISCUSSION Ophthalmic scientific meetings provide a valuable opportunity for timely dissemination of new research presented directly

to clinicians, and such poster presentations are sometimes cited by authors of practice guidelines, in journal articles or in medical textbooks. 2, 3 Although a minority of authors offer

printed reproductions of their posters for interested parties at the meeting, the official collection of abstracts is frequently the only written record of the presented research available

to delegates for reference at a later date, as not all studies will appear as publications in peer-reviewed journals. A recent Cochrane review (2007) collating data from 79 studies found

that 44.5% of studies initially presented by poster or podium presentation at scientific meetings subsequently appeared as peer-reviewed publications.1 Concern has been raised that medical

practitioners may change their practice on the basis of research that is not adequately rigorous to survive the scrutiny of peer review.4 These concerns are increased by the finding that, of

those studies that are subsequently published, the data in the peer-reviewed journal differs substantially from that initially presented at a meeting in around half of the cases.2, 3 To add

to the uncertainty surrounding the use of meeting abstracts to guide practice, this study shows that discrepancies are frequently encountered between the abstract submitted which appears in

the ‘Final Programme and Abstracts’, and the actual work presented. With the interval between the closing date for abstract submission and the meeting date typically stretching to several

months (Table 1), the possibility that authors may be speculatively submitting abstracts on the basis of incomplete research projects must be considered when reading collections of abstracts

from scientific meetings. Although some may feel that there is a legitimate case for permitting continued recruitment to a study after submission of an abstract and inclusion of the fuller

results in the final presentation of the work, the incomplete nature of the submitted abstract should be made explicit. It may be argued that, as lead-times for conferences and for journal

articles are not significantly different, if only complete datasets were to be permitted at conferences, the role of the poster might change from being a forum for the presentation of

cutting-edge work to being a promotional vehicle for the published article. In addition, if one accepts that poster presentations at conferences do provide a valuable opportunity for

presenting current work, then it may be necessary to accept the lack of the rigor, which the peer-review process provides and which gives published articles their credibility. However, the

potential for a reduction in quality is the price paid for speed. Posters are not subject to strict peer review and are not sufficiently detailed to allow another researcher to repeat the

study. As such, they fail to meet two important scientific criteria. Therefore, even if all abstracts submitted were ‘complete’ they could not be considered more valid in terms of being

referenced or used to guide practice. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to give more credence to a study known to be complete than one which may well be incomplete. We suggest that if

conference organisers are keen that researchers submit only completed studies and not those for which data collection or analysis is ongoing, submissions should be accompanied by a signed

statement that the material submitted is identical to the material to be presented. An alternative would be for an independent reviewer to randomly select a proportion of submissions and

compare the abstract to the poster, noting any significant discrepancies. We would encourage clinicians to exercise extreme caution in using printed abstracts from scientific meetings to

guide practice; the possibility that an abstract may be on the basis of interim results and draft conclusions should be borne in mind. Abstracts should therefore be regarded as an

_aide-memoire_ rather than anything more concrete to avoid basing clinical decision on unreviewed and unvalidated material. Authors should consider it a point of probity in research practice

to avoid submission of abstracts on the basis of incomplete results or analysis. Good practice would dictate that researchers should determine what sample size is necessary to answer the

research question under consideration before recruiting to a study, and refrain from submitting abstracts for presentation at scientific meetings on the basis of incomplete data. Such

practice seriously compromises the usefulness of distributed printed abstracts and could lead to inappropriate or even incorrect conclusions and recommendations being adopted into clinical

practice due to the resultant inaccuracies. Although the ultimate responsibility rests with the delegates to maintain a critical approach in evaluating presented research, a similar

responsibility lies with researchers to maintain professional integrity in the dissemination of their research findings, from the point of submission to final presentation, and organisers of

scientific meetings may wish to make more explicit the requirement to adhere to a code of practice in the presentation of research. REFERENCES * Scherer R, Langenberg P, von Elm E . Full

publication of results initially presented in abstracts. _Cochrane Database Syst Rev_ 2007 April 18; (2): MR000005. Google Scholar * Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ,

Swiontkowski MF, Sprague S _et al_. An observational study of orthopaedic abstracts and subsequent full-text publications. _J Bone Joint Surg Am_ 2002; 84-A (4): 615–621. Article Google

Scholar * Falagas ME, Rosmarakis ES . Clinical decision-making based on findings presented in conference abstracts: is it safe for our patients? _Eur Heart J_ 2006; 27 (17): 2038–2039.

Article Google Scholar * Toma M, McAlister FA, Bialy L, Adams D, Vandermeer B, Armstrong PW . Transition from meeting abstract to full-length journal article for randomized controlled

trials. _JAMA_ 2006; 295 (11): 1281–1287. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Kissy UMC Eye Hospital, Kissy, Freetown, Sierra

Leone J C Buchan * Department of Ophthalmology, St James's University Hospital, Leeds, UK D M Spokes Authors * J C Buchan View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * D M Spokes View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to J C Buchan. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION This study was presented as a poster at RCOphth Annual Congress 2008 _Conflict of interest_: None RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Buchan, J., Spokes, D. Do recorded abstracts from scientific meetings concur with the research presented?. _Eye_ 24, 695–698 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.133 Download

citation * Received: 04 October 2008 * Revised: 22 April 2009 * Accepted: 22 April 2009 * Published: 05 June 2009 * Issue Date: April 2010 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.133 SHARE

THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to

clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * posters * meeting abstracts * congresses * evidence-based practice