Symmetry and hubris | Nature

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

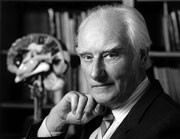

FRANCIS CRICK: HUNTER OF LIFE'S SECRETS * _Robert Olby_ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 2009. 450 pp. $45, £30 9780879697983 | ISBN: 978-0-8796-9798-3 Francis Crick: no ordinary

scientist. Credit: M. LIEBERMAN/SIEGEL & CALLAWAY Francis Crick was not your run-of-the-mill scientist, as Robert Olby makes clear in his superb biography. A tall man given to verbal

diarrhoea and infectious laughter, Crick did his Nobel-prizewinning work before he finished his PhD. His thesis, on the X-ray analysis of protein structure, provided him with skills to

appreciate the molecular arrangement of DNA, but his work with James Watson was done in his spare time. Crick included an offprint of their 25 April 1953 _Nature_ paper, the most fundamental

in twentieth-century life sciences, in the back of his thesis as proof that he was a published researcher. The Cambridge thesis was his second attempt at a doctorate. His first, in physics

at University College London, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War, during which he worked on mine research for the Admiralty. After the war, Crick convinced the Medical

Research Council (MRC) to give him a studentship to apply physics to biology. He went to Cambridge, first to the Strangeways Research Laboratory, and then to what is now known as the MRC

Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB). Discovering the structure of DNA saved his career. Lawrence Bragg, director of the Cavendish Laboratories where the LMB was then housed, had grown

tired of Crick's boisterous behaviour. After the DNA paper, Bragg held a different view and Crick stayed at the LMB until 1976. His contributions to the development of molecular biology

and genetics, and to our understanding of the genetic code and of transfer RNA, ribosomes and messenger RNA, are without parallel. His formulation of the central dogma — that information

flows in one direction, from DNA to RNA to proteins also dates from this period, along with the gradual realization that the structures and functions of molecules in cells are more

complicated than he had earlier assumed. Olby brilliantly follows Crick through these creative years. By highlighting the scientist's interactions with a growing group of others devoted

to developing the field, he captures the excitement, false dawns and triumphs that followed the Watson–Crick model of DNA. Olby is fair to all of the early participants in DNA work: Linus

Pauling, Maurice Wilkins and, above all, Rosalind Franklin and her collaborators at King's College London. Watson and Crick used Franklin's data, and benefited from a breakdown in

relations between Franklin and Wilkins that interrupted Wilkins's work on the molecule. The full story emerged only after the Nobel prize was awarded in 1962 to Watson, Crick and

Wilkins; by then, Franklin had died, tragically young, of ovarian cancer. In 1952, both Franklin and Pauling were close to coming up with the structure themselves. Issues of priority

generate passion, but Olby's account can be recommended for its dispassionate analysis and mastery of archival sources. Crick's long-time collaboration with Sydney Brenner, another

scientific giant, is given its due. So, too, are Crick's later decades spent at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, where he became a neuroscientist. Crick led a privileged

existence there, able to invite scientists whose work he admired to spend months with him. Brash young physicist turned molecular biologist; successful molecular biologist turned

neuroscientist: there is symmetry to Crick's discipline changes, but hubris as well. For Crick wanted to solve the ultimate problem, that of the physical basis of consciousness. The man

who, in 1953, supposedly announced to drinkers in The Eagle pub in Cambridge that he had discovered the secret of life, was working in 2004, on his deathbed, on a paper proposing that the

claustrum might be the key brain structure in producing consciousness. Olby works hard to put a positive spin on Crick's influence on consciousness research, in terms of support and the

number of workers in the field. He stops short of suggesting that Crick was yet another great scientist who did not know when to retire and let younger people take over. Nevertheless, that

conclusion could be drawn. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * W. F. Bynum is emeritus professor of the history of medicine at University College London and author of The History

of Medicine: A Very Short Introduction. [email protected] , W. F. Bynum Authors * W. F. Bynum View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Bynum, W. Symmetry and hubris. _Nature_ 463, 1023–1024 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/4631023a Download citation *

Published: 24 February 2010 * Issue Date: 25 February 2010 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/4631023a SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative