Adding to the antifreeze agenda

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

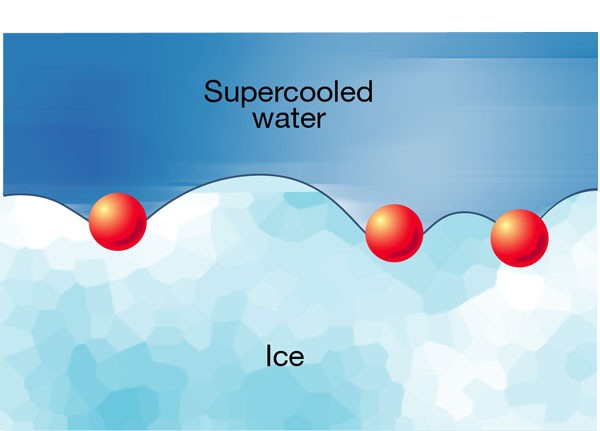

Access through your institution Buy or subscribe Antifreeze proteins allow certain organisms with no thermal control to survive cold conditions, the best known examples to date coming from

fish. Papers elsewhere in this issue1,2,3 now describe the characterization of such proteins from grass and two species of insect. They provide insights into the mysterious ways that

antifreeze proteins work. The biological ‘antifreezes’ are solutes that stick to ice crystals in supercooled water and prevent their growth. (Supercooling refers to liquids below their

freezing points; water is easily supercooled to several degrees Celsius below freezing, and remains liquid indefinitely unless nucleated.) So these molecules are unlike the antifreezes used

in internal combustion engines, which lower the freezing point by changing the properties of liquid water. As surface-active materials, small quantities of antifreeze proteins can have large

effects on surface phenomena such as crystal growth. Antifreezes from cold-water fish range upwards in relative molecular mass from 2,600, and the most active prevent ice-crystal growth

over a supercooling temperature range of just over 1 °C. In combination with dissolved salts, this is enough to protect the fish from freezing in sea water at its freezing point of −1.9 °C.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution RELEVANT ARTICLES Open Access articles citing this article. * EFFECT OF DIFFUSION KINETICS ON THE ICE NUCLEATION

TEMPERATURE DISTRIBUTION * Lorenzo Stratta * , Andrea Arsiccio * & Roberto Pisano _Scientific Reports_ Open Access 29 September 2022 * STRUCTURAL DIVERSITY OF MARINE ANTI-FREEZING

PROTEINS, PROPERTIES AND POTENTIAL APPLICATIONS: A REVIEW * Soudabeh Ghalamara * , Sara Silva * … Manuela Pintado _Bioresources and Bioprocessing_ Open Access 22 January 2022 * OSCILLATIONS

AND ACCELERATIONS OF ICE CRYSTAL GROWTH RATES IN MICROGRAVITY IN PRESENCE OF ANTIFREEZE GLYCOPROTEIN IMPURITY IN SUPERCOOLED WATER * Yoshinori Furukawa * , Ken Nagashima * … Gen Sazaki

_Scientific Reports_ Open Access 06 March 2017 ACCESS OPTIONS Access through your institution Subscribe to this journal Receive 51 print issues and online access $199.00 per year only $3.90

per issue Learn more Buy this article * Purchase on SpringerLink * Instant access to full article PDF Buy now Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

ADDITIONAL ACCESS OPTIONS: * Log in * Learn about institutional subscriptions * Read our FAQs * Contact customer support REFERENCES * Sidebottom, C. _ et al_. _Nature_ 406, 256 ( 2000).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * Graether, S. P. _ et al_. _Nature_ 406, 325–328 (2000). Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * Liou, Y.-C, Tocilj, A., Davies, P. L. & Jia, Z. _Nature

_ 406, 322–324 ( 2000). Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * DeVries, A. L. _ Science_ 172, 1153–1155 ( 1971). Article ADS Google Scholar * Knight, C. A., Cheng, C. C. & DeVries, A.

L. _Biophys. J._ 59, 409– 418 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Knight, C. A., DeVries, A. L. & Oolman, L. D. _Nature_ 308, 295– 296 (1984). Article CAS ADS Google Scholar *

Haymet, A. D. J., Ward, L. G. & Harding, M. M. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 121, 941 –948 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Uhlmann, D. R., Chalmers, B. & Jackson, K. E. _J. Appl.

Phys._ 35, 2986– 2993 (1964). Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * Asthana, R. & Tewari, S. N. _J. Mater. Sci._ 28, 5414–5425 (1993). Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * Jackson, K. A.

& Chalmers, B. _J. Appl. Phys. _ 29, 1178–1181 ( 1958). Article ADS Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * National Center for Atmospheric

Research, PO Box 3000, Boulder, 80307-3000, Colorado, USA Charles A. Knight Authors * Charles A. Knight View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Charles A. Knight. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Knight, C. Adding to the antifreeze agenda.

_Nature_ 406, 249–251 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35018671 Download citation * Issue Date: 20 July 2000 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/35018671 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative