Fda approves expanded use of blood plasma for covid-19

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

“I think what we know so far is that using convalescent plasma is safe for the people with COVID-19 who receive it, in general,” said Edward “Lalo” Cachay, professor of medicine in the

infectious disease department at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, which is one of the trial sites. “Can we with precision and accuracy say it is effective? Is it

safe for people who are seriously ill? We don’t have the data. We don’t know.” Cachay was one of many policy and science experts characterizing the FDA’s emergency use approval yesterday as

premature, saying that results from the smaller studies released so far show effects that are “marginal at best” and that questions about the time-intensive treatment’s effectiveness remain.

“We need larger trials that are ongoing to answer the questions. I hope this decision does not affect them,” he said. He added that President Donald Trump’s calling convalescent plasma

therapy a major breakthrough “does not seem to be supported by current evidence,” and noted that the FDA approved similar emergency use for hydroxychloroquine — only to reverse it when the

treatment later proved unsuccessful in patients. Shiv Pillai, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, noted that more research is also needed to suss out the basic mechanism at work

with the plasma treatment. He said plasma therapy is widely used for a lot of diseases, especially inflammatory diseases like COVID-19: “It is completely possible that what little effect

seen [is] just from the presence of plasma, and it might work if it didn’t contain the antibodies of someone who had coronavirus.” Clinical trials, he said, would provide the data to

conclude if the treatment actually targets COVID-19 or if the results seen so far were “just a random effect of immunoglobulins.” Nicole Bouvier, associate professor in the division of

infectious diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, echoed the scientific consensus that more research is needed. “We’re trying to build a wall of evidence and we’re putting

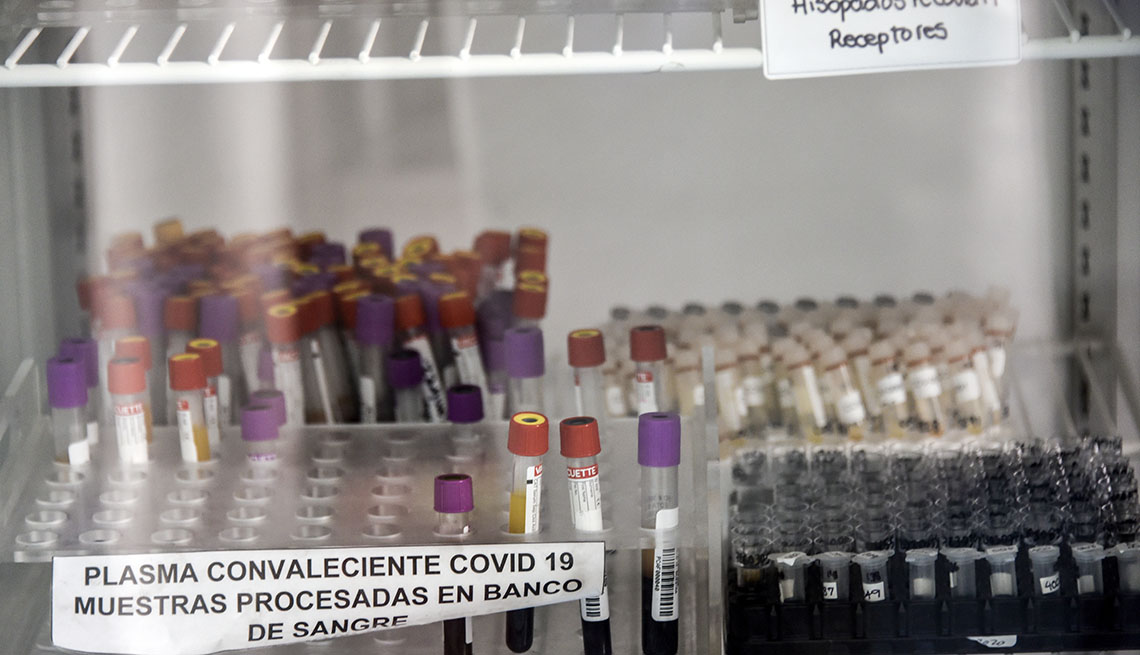

down pebbles,” she said. What’s more, she worries about there being enough plasma to go around now, since each plasma treatment — to be studied, or to be used on a patient — requires blood

donations from recovered patients. The use of convalescent plasma isn’t new; it was used during the Spanish flu pandemic in an effort to save lives. In addition to small trials here, it’s

been studied in COVID-19 patients in China and the Netherlands.